Team communication

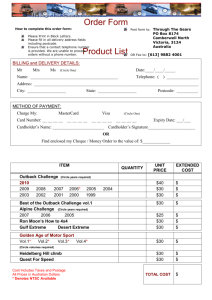

advertisement