Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 1237–1241

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Pediatric Surgery

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpedsurg

Outcome of patients after single-stage repair of perineal fistula without

colostomy according to the Krickenbeck classification

Kin Wai Edwin Chan ⁎, Kim Hung Lee, Hei Yi Vicky Wong, Siu Yan Bess Tsui, Yuen Shan Wong,

Kit Yi Kristine Pang, Jennifer Wai Cheung Mou, Yuk Him Tam

Division of Paediatric Surgery and Paediatric Urology, Department of Surgery, The Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 21 August 2013

Received in revised form 6 November 2013

Accepted 12 November 2013

Key words:

Anorectal malformation

Perineal fistula

Krickenbeck

Single stage repair

a b s t r a c t

Purpose: The aim of the study is to assess the characteristics and outcome of anorectal malformation (ARM)

patients who underwent single-stage repair of perineal fistula without colostomy according to the

Krickenbeck classification.

Methods: From 2002 to 2013, twenty-eight males and four females with perineal fistula who underwent

single-stage repair without colostomy in our institute were included in this study. Patients with perineal

fistula who underwent staged repair were excluded. Demographics, associated anomalies, and operative

complications were recorded. The type of surgical procedures and functional outcome were assessed using

the Krickenbeck classification.

Results: Six patients had associated anomalies, including two patients with renal, two with cardiac, one with

vertebral, and one with limb abnormalities. Thirteen patients underwent perineal operation, and fourteen

patients underwent anterior sagittal approach in the neonatal period. One patient underwent anterior sagittal

approach, and four patients underwent PSARP beyond the neonatal period. One patient had an intra-operative

urethral injury and one a vaginal injury. Complications were not associated with the type of surgical

procedure (p = 0.345). All perineal wounds healed without infection. By using the Krickenbeck assessment

score, all sixteen children older than five years of age had voluntary control. One patient had grade 1 soiling,

and no patient had constipation.

Conclusions: Single-stage operation without colostomy was safe with good outcomes in patients with perineal

fistula. The use of Krickenbeck classification allows standardization in assessment on the surgical approach

and on functional outcome in ARM patients.

© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Traditionally, anorectal malformations (ARM) were classified as

high, intermediate or low anomalies according to the Windspread

classification [1]. According to Peña, a colostomy was performed in all

children with ARM [2]. In children with perineal fistula, the approach

of definite repair was posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) [2].

Recently, there were reports evaluating a single-stage repair in patients with perineal fistula without a colostomy [3,4]. Anoplasty, cutback operation or anterior sagittal anorectoplasty (ASARP) was the

technique reported [3,4].

Regarding the tools used in outcome assessment, varied assessment

scoring systems were adopted worldwide [5]. With the presence of

different classification systems, it was difficult to compare the outcomes in patients with ARM between different centers.

Since the introduction of the Krickenbeck classification in 2005 [6],

there have been an increasing number of publications using this

system to classify the anatomy and assess postoperative results [7–9].

⁎ Corresponding author at: Division of Paediatric Surgery & Paediatric Urology, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital,

Hong Kong SAR, China. Tel.: +86 852 26322953.

E-mail address: edwinchan@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk (K.W.E. Chan).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.054

0022-3468/© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

However, a report which only focused on patients with perineal fistula

using the Krickenbeck classification was lacking. The assessments of

children with perineal fistula (Fig. 1) were often grouped together

with patients with vestibular fistula or with patients without a fistula

as ‘low-type’ ARM [10,11]. The aim of this study is to assess the

surgical procedures (Table 1) and outcome (Table 2) of patients with

perineal fistula using the Krickenbeck classification.

1. Materials and methods

From January 2002 to June 2013, 28 males and 4 females with

perineal fistula in our institute were included in this study. Our hospital is a tertiary referral pediatric surgical center. All patients presenting with a perineal fistula underwent single-stage repair without

protective colostomy. Patients with perineal fistula who underwent

colostomy in other hospitals or patients who underwent initial colostomy because the perineal fistula was not apparent at birth were

excluded from this study. VACTERL screening was performed in all

patients born with perineal fistula.

Demographics and associated anomalies were recorded. The surgical procedure was classified according to the Krickenbeck system.

1238

K.W.E. Chan et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 1237–1241

Table 2

International classification (Krickenbeck) for postoperative results.

1. Voluntary bowel movements

Yes/no

Feeling of urge,

capacity to verbalize,

hold the bowel movement

Fig. 1. A female with a perineal fistula.

The principle of the operation was to mobilize and place the anorectum within the sphincter complex.

2. Soiling

Yes/no

Grade 1

Grade 2

Grade 3

Occasionally (once or twice per week)

Every day, no social problem

Constant, social problem

3. Constipation

Yes/no

Grade 1

Grade 2

Grade 3

Manageable by changes in diet

Requires laxative

Resistant to laxatives and diet

fistula opening. The mobilization of anorectum and reconstitution

of the perineal body are similar to the technique described in the

anterior sagittal approach.

2. Operative technique

6. Post-operative management

Parenteral antibiotics (cefuroxime and metronidazole) were given

on induction of general anesthesia. A urethral catheter was placed

preoperatively. In neonates, the patient was positioned supine with

both legs wrapped, elevated and fixed to the handle bar of the operative table. For patients who underwent operation beyond the

neonatal period, dilatation of the fistula opening was performed

regularly before the operation. Rectal washout was performed the day

before operation. The use of the anterior sagittal approach or posterior

sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) depended on the surgeon’s preference. The center of the sphincter complex was defined by an electrical muscle stimulator. In all the cases, rectal washout was performed

after the anoplasty but before reversal of general anesthesia. The

definition of different surgical approaches was described as follows:

Parenteral antibiotics were continued for 5–7 days post-operatively. Feedings were started 2–3 days after the operation. The

perineal wound was irrigated with saline solution three times per

day in the early post-operative period. Anal dilatation was started

2 weeks after the operation. The dilatation was carried out regularly

3. Perineal operation

The patient was placed in a supine position. Only a limited perineal

dissection was required to mobilize and place the anorectum within

the sphincter complex because the fistula opening was close to the

sphincter complex (Fig. 2).

4. Anterior sagittal approach

The patient was placed in a supine position. A more extensive

mobilization of anorectum and reconstitution of the perineal body

were required in order to place the anorectum within the sphincter

complex (Fig. 3).

5. PSARP

The patient was placed in a prone position. The incision was

extended from the posterior border of the sphincter complex to the

Table 1

International grouping (Krickenbeck) of surgical procedures for follow-up.

Perineal operation

Anterior sagittal approach

Sacroperineal procedure

PSARP

Abdominosacroperineal pull-through

Abdominoperineal pull-through

Laparoscopic-assisted pull-through

Fig. 2. (A) A patient with the anorectum located slightly anterior to the sphincter

complex. (B) Perineal dissection was performed.

K.W.E. Chan et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 1237–1241

1239

had delayed diagnosis. The diagnosis of ARM was missed in the neonatal check-up. They presented with constipation and the actual

diagnosis was made at 8 and 12-months-old respectively. One patient

underwent anterior sagittal approach and the other a PSARP.

Intra-operative complications encountered in this study included

urethral injury in a boy during anterior sagittal approach and a girl

who suffered a vaginal injury during PSARP. The injuries were noted

and repaired intraoperatively with no adverse outcome. Regarding

the risk of intra-operative complication, no significant differences

were observed between the perineal operation group and the anterior

sagittal approach/PSARP group (p = 0.345) (Table 3). Post-operatively, all perineal wounds healed without infection. There were no

instances of wound dehiscence or rectal prolapse. None of the patients

required a salvage colostomy.

All 16 children older than 5 years of age had voluntary control. One

patient had grade 1 soiling and none of the patients had constipation

(Table 4). There was no instances of urinary incontinence. The two

patients with delayed diagnosis were too young for the functional

outcome assessment.

8. Discussion

Fig. 3. (A) Another patient with perineal fistula. (B) Anterior sagittal approach

was performed.

up to a 14 Hegar dilator size. A bowel management program involving

the pediatric surgeons and nurse specialists was offered to all patients.

Post-operative complications including wound infection, wound

dehiscence, rectal prolapse and the need of colostomy were recorded.

The functional outcome was assessed in patients older than 5 years of

age using the Krickenbeck classification.

Statistical analysis was accomplished using the SPSS program for

Windows 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Fisher exact test was

used to compare the categorical data with a p b 0.05 considered

statistically significant. The study was approved by the local clinical

research ethical committee.

7. Results

On VACTERL screening, 6 patients had associated anomalies. Two

patients had cardiac anomalies including one with an atrial septal

defect and one with pulmonary artery branche turbulence. Two

patients had renal anomalies including 1 with a horseshoe kidney and

1 with vesicoureteral reflux. One patient had spina bifida occulta and

one had an extra-thumb. Regarding the patient with spina bifida

occulta, the MRI did not detect any spinal cord anomaly.

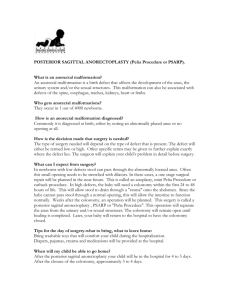

The surgical procedures performed are listed in Fig. 4. Regarding

the three patients who were diagnosed with ARM at birth but the

operation was performed beyond the neonatal period; were labeled as

anterior displaced anus at birth. Regular anal dilatation was carried

out until PSARP was performed at 1–3 months of age. Two patients

Two infants had delayed diagnosis. If the diagnosis was made at

birth, traditionally they were described as having an anterior

displaced anus. These patients were now grouped under the category

of ‘perineal fistula’ according to the Krickenbeck classification [3].

When the diagnosis was made at birth, regular dilatation of the

perineal openings was performed and effective passage of feces was

observed in the neonatal period [7]. However, children with delayed

diagnosis presented with constipation after the introduction of more

solid food as noticed in this study. In those children with this diagnosis at birth, we would delay the repair after the neonatal period

after considering the non-urgent status of this condition and to

balance the risk of general anesthesia in the neonatal period.

In performing a neonatal repair, placing the patient in the supine

position can provide excellent exposure of the perineum and

eliminate the possible adverse effects in ventilation when the neonate is placed in prone position. Harjai et al. preferred the use of

anterior sagittal approach in the management of vestibular fistula as

it may provide better exposure for the anterior dissection where

separation of the vagina and rectum takes place under direct vision

[12]. We observed the operative view when the patients were positioned in supine position was as good as the prone position.

The most obvious advantage of single-stage repair of perineal

fistula is to avoid 2 additional operations. Besides, colostomy related

complications were not uncommon [13]. Peña et al. reported 616

colostomy related complications in 464 ARM patients [13]. However,

a single-stage operation was not entirely without risk [10]. In our

study, one patient has urethral injury and one a vaginal injury. They

all underwent a more extensive sagittal approach (Table 3). The

urethra in the male and the vagina in the female were in fact in close

proximity with the fistula opening. Despite placing a urethral catheter

in all the cases, meticulous dissection is still required during dissection of the anterior rectal wall. Of course with less dissection, the

chance of injury to surrounding tissue is reduced. Pakarinen et al.

compared anoplasty to PSARP and concluded that anoplasty was safer

and less prone to complications [7]. However, since the principle of

the operative approach was different, their conclusion cannot directly

be applied in this study.

All patients were free of perineal wound infection post-operatively.

Since the majority of the cases were operated in the early neonatal

period, neonatal repair may be one of the reasons for the zero infection

rate. Albanese et al. performed a one stage repair for ‘high’ type

anorectal malformation and no perineal wound infection was observed

[14]. They suggested the neonatal bowel was theoretically sterile when

the surgery was performed. A proper peri-operative care program

1240

K.W.E. Chan et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 1237–1241

ARM with perineal

fistula

n = 32 (28M, 4F)

Diagnosis at birth

Delay in diagnosis

n = 30 (27M, 3F)

n = 2 (1M, 1F)

Operation within

Operation beyond

Anterior sagittal

PSARP

neonatal period

neonatal period

Approach

n = 1 (F)

n = 27 (26M, 1F)

n = 3 (1M,2F)

n = 1 (M)

Perineal operation

PSARP

n = 13 (12M,1F)

n = 3 (1M,2F)

Anterior sagittal

approach

n = 14 (14M)

n=number of patients, M=male, F=Female

Fig. 4. A flow chart showing the surgical procedures performed in ARM patients with perineal fistula according to the Krickenbeck classification. n = number of patients, M = male,

F = Female.

consisted of antibiotics, rectal washout and wound irrigation was

essential for successful single stage repair without the need of salvage

colostomy [15].

In this study, using the Krickenbeck classification, all patients were

free from constipation and only 1 patient had grade 1 soiling.

Constipation was reported as a major problem in patient with ‘lowtype’ ARM including patients with perineal fistula. The incidence of

constipation is around 50% in various reports [4,7,16]. Of course it was

very difficult to compare the results since the inclusion criteria of the

various studies were different. Some studies included patients with

anal stenosis or vestibular anus. Hassett et al. studied the 10 year

outcome in all ARM patients using the Krickenbeck classification after

PSARP [4]. 21% of patients with perineal fistula had grade 2 constipation

and 1 patient required a Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE),

but since this study involved all ARM patients, clinical details including

the associate anomalies and the incidence of protective colostomy in

patients with perineal fistula were not documented.

Associated anomalies, in particular spinal anomalies may have

adverse effect in the functional outcome [4]. Overall the incidence of

associated anomalies was 19% but none of the patients had spinal

cord anomalies. The incidence is lower when compared with other

reports. Hassett et al. reported 31% of patients with perineal fistula

Table 3

Relationship between the type of surgical procedures and the incidence of

complications.

Table 4

Functional outcome of the 16 children older than 5 years of age according to the

Krickenbeck assessment system.

Surgical procedures

Number of patients

Complications⁎

p value

Surgical procedures

Voluntary control

Constipation

Soiling

Perineal dissection

Anterior sagittal approach/PSARP

Total number

13

19

32

0

2

2

0.345

Perineal operation (n = 8)

Anterior sagittal approach

(n = 7)

PSARP (n = 1)

8

7

0

0

1 (Grade 1)

0

1

0

0

⁎ Complications – 1 patient had urethral injury and 1 patient had vaginal injury.

K.W.E. Chan et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 1237–1241

had associate anomalies using the Krickenbeck classification [4].

Screening for associated anomalies is required in patients with

perineal fistula [17].

We believe one of the reasons for the good functional outcome

achieved was to place the anorectum within the sphincter complex. In

contrast to previous reports, the aim of ‘anoplasty’ was not to place the

anorectum within the sphincter complex [16]. They suggested the

fistula opening although anteriorly displaced, was still partially

encased by the sphincter [7,16]. Pakarinen et al. reported there was

no difference in outcome between anoplasty and PSARP in the

management of perineal fistula [16]. In their study, 43% of children

after anoplasty and 60% children after colostomy had constipation.

However a recent study using 3D reconstruction showed the vertical

sphincter fibers did not wrapped around the distal end of the perineal

fistula [18]. The author suggested using the cutback technique it was

difficult to place the anorectum into the sphincter complex. In

addition, Lombardi et al. noticed abnormalities of the muscle coat

and the nervous system of the anorectal canal in patients with perineal

fistula. They suggested resection of the distal fistula may permit a

better functional result [19]. The majority (90%, 27/30) of patients with

the diagnosis at birth underwent primary operation within 72 hours

after birth. Even in patients who underwent anal dilatation, operation

was carried out within 3 months of age. The brain-defecation reflex

can be maintained in patients that underwent early operation and may

lead to a better functional outcome [14,20]. In addition, the implementation of a post-operative bowel management program was an

important factor that contributed to the good outcome [21].

Our experience show that single-stage repair of perineal fistula

with the aim in placing the anorectum within the sphincter complex

is safe, feasible and is associated with a good functional outcome. The

use of the Krickenbeck classification allows more standardized

documentation of the diagnosis, procedure and the outcome. A

more direct comparison of our results with future studies in other

institutions is possible.

Disclosures

Drs. Kin Wai Edwin Chan, Kim Hung Lee, Hei Yi Vicky Wong, Siu

Yan Bess Tsui, Yuen Shan Wong, Kit Yi Kristine Pang, Jennifer Wai

Cheung Mou, Yuk Him Tam have no conflicts of interest or financial

ties to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Nil.

1241

References

[1] Murphy F, Puri P, Hutson JM, et al. Incidence and Frequency of Different Types, and

Classification of Anorectal Malformations, in Holshneider AM, Hutson JM (eds):

Anorectal Malformations in Children. Springer-Verlag Berlin, pp163-84.

[2] deVries P, Pena A. Posterior anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg 1982;17:638–43.

[3] Kuijper CF, Aronson DC. Anterior or posterior sagittal anorectoplasty without

colostomy for low-type anorectal malformation: how to get a better outcome?

J Pediatr Surg 2010;45(7):1505–8.

[4] Kumar B, Kandpal DK, Sharma SB, et al. Single-stage repair of vestibular and

perineal fistulae without colostomy. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43(10):1848–52.

[5] Ochi T, Okazaki T, Miyano G, et al. A comparison of clinical protocols for assessing

postoperative fecal continence in anorectal malformation. Pediatr Surg Int 2012;

28(1):1–4.

[6] Holschneider A, Hutson J, Pena A, et al. Preliminary report on the International

Conference for the Development of Standards for the Treatment of Anorectal

Malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:1521–6.

[7] Hassett S, Snell S, Hughes-Thomas A, et al. 10-year outcome of children born

with anorectal malformation, treated by posterior sagittal anorectoplasty, assessed according to the Krickenbeck classification. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44(2):

399–403.

[8] England RJ, Warren SL, Bezuidenhout L, et al. Laparoscopic repair of anorectal

malformations at the Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital: taking stock.

J Pediatr Surg 2012;47(3):565–70.

[9] De Vos C, Arnold M, Sidler D, et al. A comparison of laparoscopic-assisted (LAARP)

and posterior sagittal (PSARP) anorectoplasty in the outcome of intermediate and

high anorectal malformations. S Afr J Surg 2011;49(1):39–43.

[10] Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ. Management and outcome of low anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:1057–63.

[11] Javid PJ, Barnhart DC, Hirschl RB, et al. Immediate and long-term results of

surgical management of low imperforate anus in girls. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33(2):

198–203.

[12] Harjai MM, Sethi N, Chandra N. Anterior sagittal anorectoplasty: An alternative to

posterior approach in management of congenital vestibular fistula. Afr J Paediatr

Surg Apr-Jun 2013;10(2):78–82.

[13] Pena A, Migotto-Krieger M, Levitt MA. Colostomy in anorectal malformations: a

procedure with serious but preventable complications. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41(4):

748–56.

[14] Albanese C, Jennings R, Lopoo J, et al. One-stage correction of high imperforate

anus in the male neonate. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:834–6.

[15] Sharma S, Gupta DK. Delayed presentation of anorectal malformation for definitive surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 2012;28(8):831–4.

[16] Pakarinen MP, Goyal A, Koivusalo A, et al. Functional outcome in correction of

perineal fistula in boys with anoplasty versus posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Pediatr Surg Int 2006;22(12):961–5.

[17] Nah SA, Ong CC, Lakshmi NK, et al. Anomalies associated with anorectal

malformations according to the Krickenbeck anatomic classification. J Pediatr

Surg 2012;47(12):2273–8.

[18] Watanabe Y, Takasu H, Mori K. Unexpectedly deformed anal sphincter in low-type

anorectal malformation. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44(12):2375–9.

[19] Lombardi L, Bruder E, Caravaggi F, et al. Abnormalities in "low" anorectal

malformations (ARMs) and functional results resecting the distal 3 cm. J Pediatr

Surg 2013;48(6):1294–300.

[20] Liu G, Yuan J, Geng J, et al. The treatment of high and intermediate anorectal

malformations: one stage or three procedures? J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:

1466–71.

[21] Schmiedeke E, Busch M, Stamatopoulos E, et al. Multidisciplinary behavioural

treatment of fecal incontinence and constipation after correction of anorectal

malformation. World J Pediatr 2008;4(3):206–10.