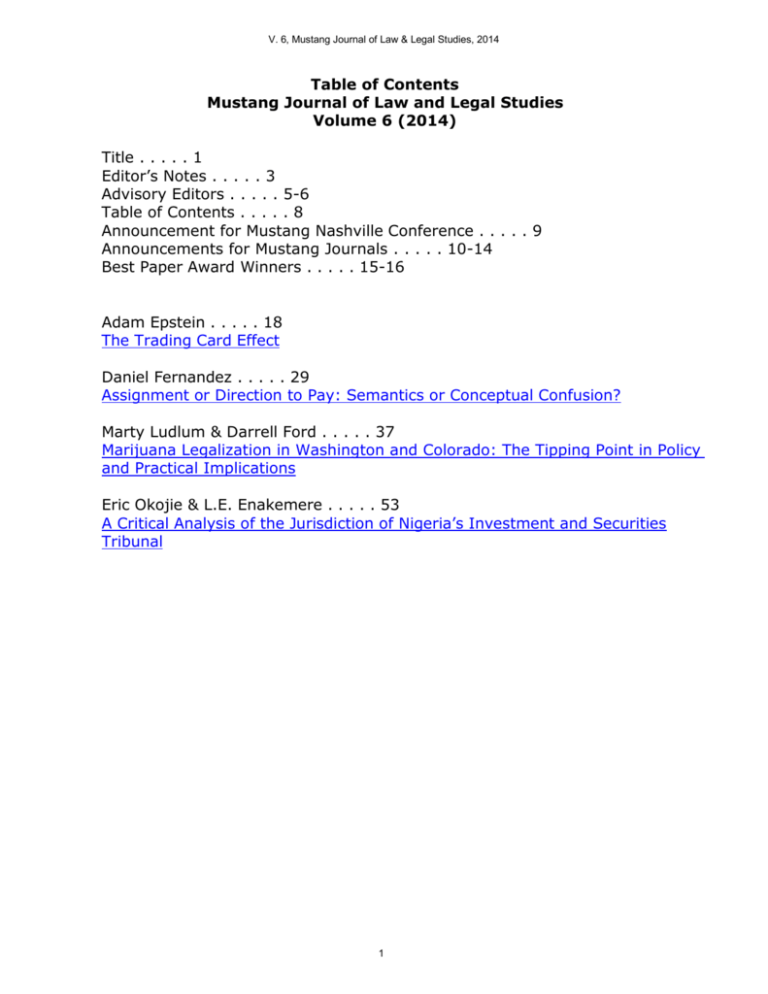

Table of Contents Mustang Journal of Law and Legal Studies

advertisement