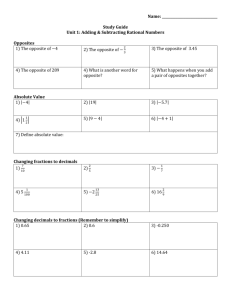

HOUSTON TEXANS STRENGTH & CONDITIONING

advertisement