GL `AFF, a Large Versatile French Lexicon

advertisement

GLÀFF, a Large Versatile French Lexicon

Nabil Hathout, Franck Sajous, Basilio Calderone

CLLE-ERSS, CNRS & Université de Toulouse

{nabil.hathout, franck.sajous, basilio.calderone}@univ-tlse2.fr

Abstract

This paper introduces GLÀFF, a large-scale versatile French lexicon extracted from Wiktionary, the collaborative online dictionary.

GLÀFF contains, for each entry, inflectional features and phonemic transcriptions. It distinguishes itself from the other available French

lexicons by its size, its potential for constant updating and its copylefted license. We explain how we have built GLÀFF and compare it

to other known resources in terms of coverage and quality of the phonemic transcriptions. We show that its size and quality are strong

assets that could allow GLÀFF to become a reference lexicon for French NLP and linguistics. Moreover, other derived lexicons can

easily be based on GLÀFF to satisfy specific needs of various fields such as psycholinguistics.

Keywords: Inflectional and phonological lexicon, free lexical resources, French Wiktionary

1.

Introduction

This article introduces GLÀFF,1 a large versatile French

lexicon extracted from Wiktionnaire, the French edition of

Wiktionary. Wiktionnaire contains more than 2 million articles, each including definitions, pronunciations, translations and semantic relations. GLÀFF aims to make this

resource available for NLP systems and linguistic research

in a workable format.

Some French morphological lexicons, such as

Lefff (Clément et al., 2004) and Morphalou (Romary

et al., 2004), are freely available. These resources contain

inflected forms, lemmas and morphosyntactic tags. They

do not include, however, phonemic transcriptions that are

necessary in phonology and in the design of tools such as

phonetizers. Lexique (New, 2006), another free lexicon,

contains phonemic transcriptions but has a restricted coverage. While this lexicon is popular in psycholinguistics,

its sparsity in terms of inflected forms prevents its use in

NLP. Resources that have both exploitable coverage and

phonemic transcriptions, such as BDLex (Pérennou and de

Calmès, 1987), ILPho (Boula De Mareuil et al., 2000) or

GlobalPhone (Schultz et al., 2013) are not free. Besides

the cost, derivative works cannot be redistributed, which

constitutes an impediment for collaborative research.

As of today, no French lexicon meets all following requirements: free license, wide coverage, and phonemic transcriptions. Wiktionnaire may be a candidate resource for

the creation of such a lexicon. Wiktionary was first used

for NLP by Zesch et al. (2008) to compute semantic relatedness. Its potential as an electronic lexicon was first studied for English and French by Navarro et al. (2009). Other

works tackled data extraction from other language editions.

Anton Pérez et al. (2011) describe the integration of the

Portuguese Wiktionary and Onto.PT (Gonçalo Oliveira and

Gomes, 2010). Sérasset (2012) built Dbnary, a multilingual network containing “easily extractable” entries. For

French, the resulting graph includes 260,467 nodes. OntoWiktionary (Meyer and Gurevych, 2012), an ontology

based on Wiktionary, and UBY (Gurevych et al., 2012), an

alignment of 7 resources including WordNet, Germanet and

1

GLÀFF is freely available at http://redac.

univ-tlse2.fr/lexicons/glaff_en.html

Wiktionary, constitute the most complete resources based

on Wiktionary. A detailed characterization of the English

and French editions of Wiktionary is given in (Sajous et

al., 2010; Sajous et al., 2013b). These papers also present

the extraction process of WiktionaryX,2 an XML-structured

lexicon containing definitions, semantic relations and translations. GLÀFF is a new step focusing on the extraction of

inflected forms and phonemic transcriptions that were absent from the previous resource.

Wiktionary’s language editions are released as “XML

dumps”, where only the macrostructure is marked by XML

tags. The microstructure is encoded in a format called wikicode, whose syntax is not formally defined, evolves over

time, and is not stable from one language edition to another. Due to this underspecified syntax, a parser has to

expect multiple deviations from the “prototypical article”

and must handle missing information, redundancy and inconsistency. For example, the gender or pronunciation may

be missing in an inflected form’s article, but occur in the

one dedicated to its lemma. Sometimes, contradictory information may occur in both articles. To build GLÀFF, we

designed an extractor that collects the maximum amount of

information from Wiktionary’s articles (lemmas, inflected

forms and conjugation tables) and applies a set of rules to

output a structured and (as much as possible) consistent inflectional and phonological lexicon.

2.

Resource description

GLÀFF contains more than 1.4 million entries including

nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and function words. As

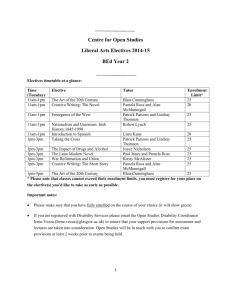

illustrated in Figure 1, each entry contains a wordform, a

tag in GRACE format (Rajman et al., 1997), a lemma and

an IPA transcription, when present in Wiktionnaire. Entries also contain word frequencies computed over different corpora. Sajous et al. (2013a) give a first description of GLÀFF. We characterize GLÀFF below in terms of

coverage (section 2.1.) and phonemic transcriptions (section 2.2.). In section 2.3., we present newly added features.

2

WiktionaryX is freely available at: http://redac.

univ-tlse2.fr/lexicons/wiktionaryx_en.html

1007

affluent|Afpms|affluent|a.fly.ã|12|0.41|15|0.51|175|0.79|183|0.83|576|0.45|696|0.55

affluente|Afpfs|affluent|a.fly.ãt|0|0|0|0|2|0.00|183|0.83|9|0.00|696|0.55

affluentes|Afpfp|affluent|a.fly.ãt|1|0.03|15|0.51|1|0.00|183|0.83|22|0.01|696|0.55

affluent|Ncms|affluent|a.fly.ã|22|0.76|38|1.31|232|1.05|444|2.02|1234|0.98|3655|2.91

affluents|Afpmp|affluent|a.fly.ã|2|0.06|15|0.51|5|0.02|183|0.83|89|0.07|696|0.55

affluents|Ncmp|affluent|a.fly.ã|16|0.55|38|1.31|212|0.96|444|2.02|2421|1.93|3655|2.91

affluent|Vmip3p-|affluer|a.fly|9|0.31|187|6.48|369|1.67|1207|5.49|500|0.39|1929|1.53

affluent|Vmsp3p-|affluer|a.fly|9|0.31|187|6.48|369|1.67|1207|5.49|500|0.39|1929|1.53

Figure 1: Extract of GLÀFF

Lexique

BDLex

Lefff

Morphalou

GLÀFF

Categorized inflected forms

Simples Non simples

Total

147,912

4,696

152,608

431,992

4,360

436,352

466,668

3,829

470,497

524,179

49

524,228

1,401,578

24,270 1,425,848

Categorized lemmas

Simples Non simples

Total

46,649

3,770

50,419

47,314

1,792

49,106

54,214

2,303

56,517

65,170

7

65,177

172,616

13,466 186,082

Table 1: Size of the lexicons (restricted to nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs).

2.1.

Coverage

GLÀFF differs from the lexicons currently used in NLP and

psycholinguistics by its exceptional size. Table 1 shows

the number of lemmas and inflected forms, simple (letters

only) and non-simple (containing spaces, dashes or digits).

GLÀFF contains 3 to 4 times more tokens and 3 to 9 times

more forms. This size is an important asset when the lexicon is used for research in derivational or inflectional morphology. It is also an advantage for the development of

NLP tools as morphosyntactic taggers and parsers. The table also shows that GLÀFF contains numerous multi-word

expressions (MWE) that can improve text segmentation and

subsequent processing.

The following comparisons only concern nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. They were carried out on simple inflected forms and lemmas in order to ignore differences in

the treatment of MWEs and corpora segmentation. MWEs

(i.e. the 24 270 non simple forms –resp. 13 466 non simple

lemmas–) have been discarded from the version of GLÀFF

presented in this paper and will be added in a future version.

We first study the intersection of GLÀFF and other lexicons. We observe in Table 2 that the size of the intersections

directly depends on that of the lexicons: the bigger a lexicon, the larger its intersection with the other ones. The five

lexicons fall into three groups. Lexique has a smaller coverage. It only contains 9% of GLÀFF entries and 22% to 26%

of the entries of other lexicons. BDLex, Lefff and Morphalou cover 76% to 80% of Lexique and 30% of GLÀFF

in average. GLÀFF is clearly above with a coverage of 85%

to 93%. Its coverage is 5% to 65% larger than the ones of

the other lexicons.

GLÀFF is considerably larger than all other lexicons,

which potentially is an asset. In order to check that this

advantage is real (i.e. that having a greater number of lexemes and inflected forms is actually useful), we compared

the five lexicons to the vocabulary of three corpora of various types. LM10 is a 200 million word corpus made up of

the archives of the newspaper Le Monde from 1991 to 2000.

The second corpus, containing 260 million word, consists

of articles from the French Wikipedia. Finally, FrWaC (Baroni et al., 2009) is a 1.6 billion word corpus of French web

pages (spidered from the .fr domain).

Table 3 shows the coverage of the five lexicons with respect to the three corpora. The vocabulary is restricted to

the forms of frequency greater than or equal to 1, 2, 5, 10,

100 and 1000. The ranking of the corpora by coverage

is the same for the five lexicons. Although their size affects the order, their nature is also crucial. For example,

FrWaC being a collection of web pages, it contains a large

number of “noisy” forms (foreign words, missing or extra

spaces, missing diacritics, random spelling, etc.). Again,

we see the division of lexicons into three groups. BDLex,

Lefff and Morphalou have a quite close coverage. Lexique

has the smallest coverage up to the 100 threshold. GLÀFF

has the largest coverage for all corpora, except for LM10 at

the 1000 threshold where it is surpassed by Lefff by 0.2%.

For the other corpora and up to the 100 threshold, the size

of GLÀFF explains its larger coverage with respect to the

other lexicons (at the threshold 1, 14% to 53% larger for

LM10 and 30% to 120% larger for FrWaC; at the threshold 10, 4% to 16% for LM10 and 15% to 47% for FrWaC).

NLP tools that integrate GLÀFF should therefore offer an

improved performance in the treatment of these corpora.

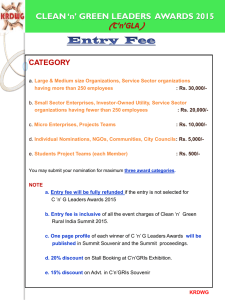

Figure 2 compares the lexicons’ coverage from another perspective: for each lexicon, it represents the number of forms

having a corpus frequency within a given interval. We still

Lexique

Lexique

BDLex

Lefff

Morph.

GLÀFF

76.0

79.5

79.6

84.8

BDLex

26.0

86.3

85.4

93.3

Lefff

25.2

79.9

81.2

90.2

Morph.

22.5

70.4

72.3

GLÀFF

8.9

28.8

30.1

32.0

85.7

Table 2: Coverage w.r.t. the other lexicons (% of categorized inflected forms).

1008

Threshold: frequency ≥

# forms

Lexique

BDLex

LM10

Lefff

Morphalou

GLÀFF

# forms

Lexique

BDLex

Wikipédia

Lefff

Morphalou

GLÀFF

# forms

Lexique

BDLex

FrWaC

Lefff

Morphalou

GLÀFF

1

300,606

29.59

37.77

39.64

39.06

45.24

953,920

9.13

12.29

12.88

13.05

16.42

1,624,620

5.83

9.36

9.85

10.09

13.13

2

172,036

47.28

55.79

58.22

56.82

63.83

435,031

18.27

22.89

23.94

23.96

29.00

846,019

10.85

15.85

16.67

16.89

21.13

5

106,470

65.23

71.76

74.33

71.92

78.63

216,210

31.52

36.80

38.26

37.87

44.13

410,382

20.84

27.28

28.57

28.53

34.29

10

77,936

76.31

80.93

83.20

80.32

86.23

136,531

43.03

48.04

49.65

48.87

55.45

255,718

30.81

37.48

39.16

38.68

45.35

100

29,388

93.81

95.53

95.99

93.27

96.46

35,621

78.58

79.39

80.57

78.74

83.21

74,745

66.00

69.61

71.61

69.36

76.39

1000

7,838

98.58

98.69

98.90

97.48

98.68

7,956

95.72

95.33

95.71

94.16

96.10

22,100

89.47

90.03

91.16

88.51

92.76

Table 3: Lexicon/corpus coverage (% of non-categorized inflected forms).

observe the distribution of the lexicons into 3 groups. The

diagram also shows that even for very frequent and well established words, with a frequency between 101 and 1000,

GLÀFF’s coverage remains the largest. Table 3 and Figure 2 show that the superiority of GLÀFF is stronger for

heterogeneous corpora and for low and medium frequency

words. We complete the characterization of GLÀFF’s coverage by focusing on its specific vocabulary, i.e. on the

forms that are missing in the other four lexicons. Table 4

shows the number of forms that occur in the corpus for each

sub-vocabulary. In accordance with intuition, the number

of inflected forms increases with corpus size. The size of

the corpus, however, does not explain all. A large portion of the specific vocabulary consists of inflected verb

forms, because GLÀFF includes all their possible inflec-

10

x 10

tions. GLÀFF also contains less normative and more recent

French words which tend to appear in heterogeneous corpora such as FrWaC. Even for a newspaper corpus whose

most recent year is 2000 (LM10), Wiktionary’s “youth”

and constant updating allow GLÀFF to cover a number

of quite usual words such as: attractivité ‘attractivity’,

brevetabilité ‘patentability’, diabolisation ‘demonization’,

employabilité ‘employability’, homophobie ‘homophobia’,

hébergeur ‘host’, fatwa, institutionnellement ‘institutionally’, anticorruption ‘anti-corruption’, etc. missing from

the other lexicons.

Lexique

BDLex

Lefff

Morphalou

GLÀFF

4

GLÀFF

Morphalou

Lefff

BDLex

Lexique

9

8

Specific

forms

1 509

3 981

11 050

26 881

665 290

Number of attested forms

LM10 Wikipédia FrWaC

863

1 073

1 320

521

1 004

1 496

1 479

2 214

3 288

1 912

3 995

6 425

13 525

29 230

47 549

Table 4: Attestation of the lexicons’ specific vocabulary in

the corpora.

Number of forms

7

2.2.

6

5

4

3

2

1

1-10

11-102

101-103

1001-104

10001-105 100001-106

Frequency intervals

Figure 2: Distribution of forms w.r.t. their corpus frequency.

Phonemic transcriptions

GLÀFF provides a phonemic transcription for about 90%

of the entries. We evaluated the consistency of these transcriptions with respect to those of BDLex and Lexique (after conversion into IPA encoding). Two types of comparisons were performed: a) phonological transcriptions; b)

syllabification (only for matching transcriptions). Tables

5a to 5c report the top ten variations between pairs from

the three lexicons. We only considered one phoneme differences, ignoring syllabification. Table 5d illustrates such

differences by reporting, for a small set of words, examples

of transcription adopted by the three lexicons and, in the

last column, additional transcriptions taken from the Dictionnaire de la Prononciation Française dans son Usage

1009

Oper.

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

d

Phonemes

E/e

O/o

o/O

y/4

@/ø

@/œ

u/w

b/p

s/z

j

%

48.18

32.17

11.02

1.83

1.44

1.39

0.84

0.73

0.51

0,25

P

%

48.18

80.36

91.37

93.21

94.64

96.03

96.87

97.61

98.12

98,37

Oper.

r

i

r

r

r

r

r

r

i

r

(a) BDLex/Lexique

Operation

r : E/e

r : s/z

r : b/p

r : o/O

r : @/ø/œ

r : y/4

r : u/w

r : a/A

i,d : i,j

i,d : @

Phonemes

O/o

@

e/E

E/e

A/a

s/z

@/ø

œ/ø

i

o/O

%

60.03

14.18

6.90

4.98

4.92

1.25

0.91

0.47

0.42

0.38

P

%

60.03

74.21

81.11

86.09

91.01

92.26

93.17

93.64

94.06

94.44

Oper.

r

r

i

r

r

r

r

r

i

r

(b) GLÀFF/Lexique

Form

été

stalinisme

obturer

pomme

heureux

gradué

jouer

inouı̈

pâte

riiez

contenu

BDLex

/E.te/

/sta.li.nis,m/

/Ob.ty.Ke/

/po,m/

/@.Kø/

/gKa.dy.e/

/Zu.e/

/i.nu.i/

/pa,t/

/Ki.i.je/

/kÕ,t@.ny/

Transcriptions

Lexique

GLÀFF

/e.te/

/e.te/

/sta.li.nizm/ /sta.li.nism/

/Op.ty.Ke/

/Op.ty.Ke/

/pOm/

/pOm/

/ø.Kø/

/œ.Kø/

/gKa.d4e/

/gKa.d4e/

/Zwe/

/Zwe/

/i.nwi/

/i.nwi/

/pat/

/pAt/

/Ki.je/

/Kij.je/

/kÕ.t@.ny/

/kÕt.ny/

Phonemes

e/E

O/o

@

o/O

A/a

4/y

œ/@

ø/@

i

w/u

%

66.46

10.58

5.90

4.36

3.84

1.61

1.09

0.86

0.84

0.79

P

%

66.46

77.05

82.96

87.32

91.17

92.78

93.88

94.74

95.58

96.38

(c) GLÀFF/BDLex

DPF

/ete/

/stalinism/, /stalinizm/

/Optyre/, /Obtyre/

/pOm/

/ørø, œrø/

/grad4e/, /grAd4e/, /gradye/

/Zwe/, /Zue/

/inwi/, /inui/

/pat/ , /pAt/

/kÕt(@)ny/

(d) Examples of inter-lexicons differences of phonemic transcription.

Table 5: The 10 most frequent differences in transcription.

Operations: r = replacement ; i = insertion ; d = deletion.

Lexicon

BDLex Lexique

GLÀFF Lexique

GLÀFF BDLex

Intersection

112,439

123,630

396,114

Phonological transcription

Identical

Comparable

58.31

96.88

79.50

97.81

61.72

96.88

Syllabification

Identical

98.92

98.48

98.30

Table 6: Inter-lexicon agreement: phonological transcriptions and syllabification

Réel (Martinet and Walter, 1973), or DPF. This dictionary

stems from a study of French pronunciation carried out in

1968-1973 involving 17 French speakers in order to test differences in production for individual words.

The differences in transcriptions between GLÀFF and the

other two lexicons are comparable to the differences observed between BDLex and Lexique. In particular, these

differences are mostly due to the distinctions between the

mid vowels, i.e. the front-mid vowels: [e] (close-mid) vs.

[E] (open-mid) and the back-mid vowels: [o] (close-mid)

vs. [O] (open-mid). This alternation is a well known aspect of French phonology resulting from diatopic variations

(North vs. South), as described in (Detey et al., 2010). Such

expected oppositions accounts for about 91% of the divergences between BDLex and Lexique.

Table 6 reports the percentage of identical phonological

transcriptions shared by the lexicons and the percentage

of the ‘comparable’ phonological transcriptions, i.e. disregarding the distinction between close-mid and open-mid

vowels. GLÀFF and Lexique give identical transcriptions for 79.5% of entries whereas the percentage between

GLÀFF and BDLex is lower, at 61.7%. Table 6 also reports

the results of the comparison of syllabification in the three

lexicons (performed on the basis of identical transcriptions

only). This comparison shows that the three lexicons are

quite similar with respect to syllabification (98%).

A crowdsourced resource like Wiktionary may reveal some

amateursims. However, crowdsourcing is interesting from

a linguistic point of view because it reflects the language

perception of speakers rather than of linguists. For example, word-medial consonant clusters like /s/ + C are treated

in GLÀFF sometimes as heterosyllabic clusters, as in ministère /mi.nis.tEK/ ‘ministry’, with the /s/ and the following consonant assigned to distinct syllables (corresponding

to the canonical analysis in French phonological tradition),

and sometimes as tautosyllabic clusters, as in monistique

/mO.ni.stik/ ‘monistic’. Such examples can reveal areas

of non-deterministic variation that standard lexicographic

1010

Figure 3: GLÀFFOLI, the GLÀFF OnLine Interface

conventions tend to minimize.

2.3.

Additional features

Version 1.2 of GLÀFF comes with form and lemma frequencies (absolute and relative) computed over different

corpora including LM10 and FrWaC (cf. Figure 1).

Another novelty is the possibility of browsing GLÀFF online thanks to the GLÀFFOLI interface,3 as illustrated in

Figure 3. This interface enables any user to build a multicriteria query. Request fields may include wordform,

lemma, part of speech and/or pronunciation written in IPA

or SAMPA. These fields are matched against GLÀFF entries through regular expressions or operators such as is,

contains, starts with, ends with, etc. depending on the

user’s choice. Display is customizable and, when corpora

frequencies are visible, the wordforms attested in FrWaC

are linked to the NoSkecthEngine (Rychlý, 2007) concordancer.

3.

Conclusion

We presented a new French lexicon built automatically

from Wiktionary. This lexicon is remarkable for its size.

It provides morphosyntactic descriptions for 1.4 million

entries and phonemic transcriptions for 1.3 million of them.

Despite its very large size, the overall quality of GLÀFF is

very good as shown by various comparisons with similar

resources including Lexique, Lefff and BDLex.

Among the directions for future research, we plan an

evaluation of the contribution of GLÀFF to syntactic

parsing using the Talismane parser (Urieli, 2013).

In the near future, we also plan to unify GLÀFF and WiktionaryX to give access to definitions and semantic relations in addition to inflectional and phonological information. Such a resource will be useful for NLP but also for

linguistic descriptions. More generally, multiple specific

lexicons may be derived from GLÀFF, depending on the

needs. For example, we illustrated in (Calderone et al.,

3

http://redac.univ-tlse2.fr/glaffoli/

2014) how we have built a psycholinguistics-oriented lexicon from GLÀFF by adding an extended set of features that

are used to set up experimental material in this field.

4.

References

Anton Pérez, L., Gonçalo Oliveira, H., and Gomes, P.

(2011). Extracting Lexical-Semantic Knowledge from

the Portuguese Wiktionary. In Proceedings of the 15th

Portuguese Conference on Artificial Intelligence, EPIA

2011, pages 703–717, Lisbon, Portugal.

Baroni, M., Bernardini, S., Ferraresi, A., and Zanchetta, E.

(2009). The WaCky wide web: a collection of very large

linguistically processed web-crawled corpora. Language

Resources and Evaluation, 43(3):209–226.

Boula De Mareuil, P., Yvon, F., D’Alessandro, C.,

Aubergé, V., Vaissière, J., and Amelot, A. (2000).

A French Phonetic Lexicon with variants for Speech

and Language Processing. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Language Resources

and Evaluation (LREC 2000), pages 273–276, Athens,

Greece.

Calderone, B., Hathout, N., and Sajous, F. (2014). From

GLÀFF to PsychoGLÀFF: a large psycholinguisticsoriented French lexical resource. In Proceedings of the

16th EURALEX International Congress, Bolzano, Italy.

Clément, L., Lang, B., and Sagot, B. (2004). Morphology based automatic acquisition of large-coverage lexica. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC

2004), pages 1841–1844, Lisbon, Portugal.

Detey, S., Durand, J., Laks, B., and Lyche, C. (2010). Les

variétés du français parlé dans l’espace francophone.

L’essentiel francais. Ophrys.

Gonçalo Oliveira, H. and Gomes, P. (2010). Onto.PT:

Automatic Construction of a Lexical Ontology for Portuguese. In Proceedings of 5th European Starting AI Researcher Symposium, pages 199–211, Lisbon, Portugal.

Gurevych, I., Eckle-Kohler, J., Hartmann, S., Matuschek,

M., Meyer, C. M., and Wirth, C. (2012). UBY - A

Large-Scale Unified Lexical-Semantic Resource Based

on LMF. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of

1011

the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL 2012), pages 580–590, Avignon, France.

Martinet, A. and Walter, H. (1973). Dictionnaire de la

Prononciation Française dans son Usage Réel. France

Expansion.

Meyer, C. M. and Gurevych, I. (2012). OntoWiktionary

– Constructing an Ontology from the Collaborative Online Dictionary Wiktionary. In Pazienza, M. T. and

Stellato, A., editors, Semi-Automatic Ontology Development: Processes and Resources, chapter 6, pages 131–

161. IGI Global, Hershey, PA, USA.

Navarro, E., Sajous, F., Gaume, B., Prévot, L., Hsieh, S.,

Kuo, I., Magistry, P., and Huang, C.-R. (2009). Wiktionary and NLP: Improving synonymy networks. In

Proceedings of the 2009 ACL-IJCNLP Workshop on The

People’s Web Meets NLP: Collaboratively Constructed

Semantic Resources, pages 19–27, Singapore.

New, B. (2006). Lexique 3 : Une nouvelle base de données

lexicales. In Verbum ex machina. Actes de la 13e

conférence sur le Traitement Automatique des Langues

Naturelles (TALN’2006), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgique.

Pérennou, G. and de Calmès, M. (1987). BDLEX lexical

data and knowledge base of spoken and written French.

In Proceedings of the European Conference on Speech

Technology, ECST 1987, pages 1393–1396, Edinburgh,

Scotland.

Rajman, M., Lecomte, J., and Paroubek, P. (1997). Format

de description lexicale pour le français. Partie 2 : Description morpho-syntaxique. Technical report, EPFL &

INaLF. GRACE GTR-3-2.1.

Romary, L., Salmon-Alt, S., and Francopoulo, G. (2004).

Standards going concrete: from LMF to Morphalou. In

Zock, M. and Saint-Dizier, P., editors, COLING 2004

Enhancing and using electronic dictionaries, pages 22–

28, Geneva, Switzerland.

Rychlý, P. (2007). Manatee/Bonito - A Modular Corpus

Manager. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Recent Advances in Slavonic Natural Language Processing, pages 65–70, Brno, Czech Republic.

Sajous, F., Navarro, E., Gaume, B., Prévot, L., and Chudy,

Y. (2010). Semi-automatic Endogenous Enrichment of

Collaboratively Constructed Lexical Resources: Piggybacking onto Wiktionary. In Loftsson, H., Rögnvaldsson, E., and Helgadóttir, S., editors, Advances in Natural Language Processing, volume 6233 of LNCS, pages

332–344. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg.

Sajous, F., Hathout, N., and Calderone, B. (2013a).

GLÀFF, un Gros Lexique À tout Faire du Français. In

Actes de la 20e conférence sur le Traitement Automatique des Langues Naturelles (TALN’2013), pages 285–

298, Les Sables d’Olonne, France.

Sajous, F., Navarro, E., Gaume, B., Prévot, L., and Chudy,

Y. (2013b). Semi-automatic enrichment of crowdsourced synonymy networks: the WISIGOTH system

applied to Wiktionary. Language Resources and Evaluation, 47(1):63–96.

Schultz, T., Vu, N. T., and Schlippe, T. (2013). GlobalPhone: A multilingual text & speech database in 20

languages. In Proceedings of Conference on Acoustics,

Speech, and Signal Processing, pages 8126–8130, Vancouver, Canada.

Sérasset, G. (2012). Dbnary: Wiktionary as a LMF based

Multilingual RDF network. In Proceedings of the Eigth

International Conference on Language Resources and

Evaluation (LREC 2012), Istanbul, Turkey.

Urieli, A. (2013). Robust French syntax analysis: reconciling statistical methods and linguistic knowledge in the

Talismane toolkit. Ph.D. thesis, Université de ToulouseLe Mirail.

Zesch, T., Müller, C., and Gurevych, I. (2008). Extracting

Lexical Semantic Knowledge from Wikipedia and Wiktionary. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC

2008), Marrakech, Morocco.

1012