private and Social Costs of Cash and Card

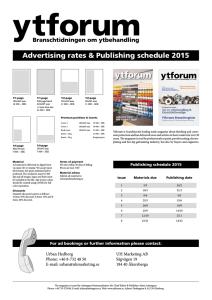

advertisement