HOW DO YOU READ PHILLIS WHEATLEY

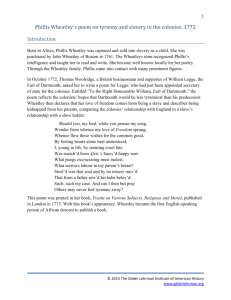

advertisement

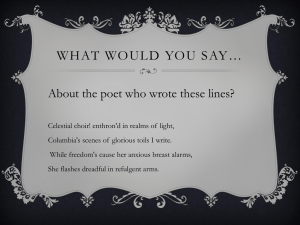

HOW DO YOU READ PHILLIS WHEATLEY?: IMPLICATIONS FOR PEDAGOGY …As to her Writing, her own Curiosity led her to it; and this she learnt in so short a Time, that in the year 1765, she wrote a Letter to the Rev. Mr. Occom, the Indian Minister, while in England. – John Wheatley, Boston, Nov. 14, 1772. How do you read Phillis Wheatley? Are you one of those who do not hesitate to dismiss her as a “derivative” or “imitator” of Alexander Pope and the neoclassical tradition? Do you see her as not being race conscious in her works? Or do you regard her poetry as the product of “a white mind” because it does not vehemently condemn slavery? If you are, then, this paper challenges you to reconsider your reading habits and be “refin’d.” If you are not, then, let us join the poet on her “angelic train” to explore the moral and religious subjects that she addresses. You can see what I have begun doing already. I contend that Phillis Wheatley is a complex writer who wrote for two different types of audiences – the immediate (local) and narrow readership as well as the remote and broad category of readers. Certain reactions to her works give us the dichotomy. The local audience is made up of those who do a superficial reading of her poetry, paying attention to only the surface meaning of her words and allusions, and conclude that she is the product of a “white mind” while the second category goes beyond the superficial to see hidden truths that make them establish that she is a “natural genius.” Where do you belong? My paper examines the rhetorical project of Phillis Wheatley, using the title of her 1773 published works (Poems on Various Subjects Moral and Religious) as the framework. The operative words for the discussion are “various subjects,” “moral,” and religious. I argue that Phillis Wheatley’s poetry is an amalgam of everything that debunks 1 her critics’ calumny that she is nothing but an imitator of the neoclassical poetic tradition introduced by Pope but which they either fail or refuse to appreciate. My discussion will first involve an exploratory survey of her poetry, beginning with an identification of what types of poems she wrote, and why she chose those genres, and how she interrogated the themes. More essentially, I will base my argument on the rhetorical project that drove her poetry, using evidence from her own works, with the view to establishing that Phillis Wheatley was no imitator of anybody’s dispensation or works. I opine that she is not being given due recognition as the precursor of the (African) American literary tradition of elegiac poetry. Eventually, I will propose measures for the teaching of her works that should help us counteract the denigration by her critics. In this effort, my intention is to draw attention to what can be done to promote a better teaching and learning of Phillis than has been the case hitherto. It will be my contribution towards the efforts at immortalizing Phillis Wheatley as the precursor of the literary culture that derives its strength from the combined use of genres to accomplish the five aesthetic categories – the imagination, the sublime, the picturesque, the beautiful, and taste. I begin the discussion with the claims and counter claims of scholars. Though Vernon Loggins labels Phillis wrongly as an “occasional” poet, he gives us a clear picture about the extent of her poetry. The scope of my paper demands that I mention the various works that Phillis wrote so that we could place an assessment of her in the proper context. According to Loggins, 18 out of Phillis’ 42 poems are elegies (consolatory poems at the request of friends; five of them are on Ministers of the Christian religion; two on the wives of a Lt.-Governor and a celebrated physician; the rest 2 are on unknown persons, including a number of children who died in infancy). He reveals that six of Phillis’ poems were inspired by public events of importance (such as the repeal of the Stamp Act, appointment of George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the Revolutionary forces, betrayal of General Lee into the hands of the British, and the return of peace at the close of the Revolution). A number of her poems are also on minor happenings – voyage of a friend to England, and the providential escape of an acquaintance from a hurricane at sea. Phillis used paraphrases too, versifying selections from the Bible (a custom in the New England, begun in the early days when the Bay Psalm Book was compiled). In all, she versified eight selections, including the 53rd chapter of Isaiah, and the passage in First Samuel which describes David’s fight with Goliath. She also adapts a portion of the sixth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which tells of Niobe’s distress for her children. Furthermore, Phillis wrote poems on abstractions (“On Imagination,” “On Virtue,” “On Recollection,” and “Thoughts on the Works of providence,” among others.) She also wrote companion hymns (“An Hymn to the Morning” and “An Hymn to the Evening,”) She wrote prose (letters) too. The complexity of her literary repertoire emerges and we should begin to relate to it with the appropriate disposition. Wide-ranging as Phillis’ writings were, they should be expected to cover several themes at both the superficial and profound levels. It is not surprising that on the surface, the themes relate to Christian piety, morality, virtue, death, praise of classical heroes, and a celebration of abstractions. A deep reading of her works will, however, reveal their anti-slavery sentiments and her protest against the oppression of her race. She protests, stresses vengeance, and uses her powerful imagery to draw attention to her search for 3 power, order, and progress. The recurrence of the sun imagery, train, painting, and refinement speaks volumes about the hidden agenda in her works, which will take more than a superficial reading to unravel. Phillis Wheatley has never ceased to attract attention ever since she shot herself into the limelight with the release of her elegy on the death of the Reverend George Whitefield in 1770, through Thomas Jefferson’s outright condemnation of her in his 1782 Notes on the State of Virginia, and through the outbursts against her in the period of the Harlem Renaissance to date by critics who read “race” and “social status” into her poetry rather than examining her rhetorical project and complex strategies used to project her views on moral and religious subjects. Though these critics’ views, to me, have become hackneyed, they will serve some purposes of this paper if brought up for reference. The driving force of this audience’s reading of Phillis comes from their ascription of “race” and “social status” to her worth. The tone for my discussion of the import of criticism of her work comes from two conflicting eighteenth century reviews that are important only because they fall in the first category of superficial readers of Phillis. In one breath, the first part of the review says that the poems “display no astonishing power of genius” but have special merit because of their singular author. In the same breath, we get “most [black] people have a turn for imitation, though they have little or none for invention” (Black Literature Criticism, 1879; Poetry Criticism, 331). Snatching at the slant of this criticism, M.A. Richmond blames Phillis’ “artificiality” on Pope’s neoclassicism. According to him, neoclassicism encased Phillis Wheatley within the “tyranny of the couplet” and crushed her talent under “the heavy burden of ornamental rhetoric,” adding that it taught her regularity. Other critics accuse 4 Phillis of “artificiality” and “insincerity” in her poetry, saying that it was the result of the practice in the eighteenth century. This criticism is at best wrongheaded, according to available evidence on the relationship between “artificiality” and “neoclassicism” in the eighteenth-century literary practice. Scruggs (1981) debunks any association of “artificiality” to “neoclassicism,” in eighteenth century concept, saying that its use was not pejorative, though it could be used as such. To him, “artificial” meant “artful, contrived with skill” (Black Literature Criticism, 1890). He strongly maintains that eighteenth-century poetry made a distinction between “artifice” and “artificiality” and not between “sincerity” and “artificiality.” Thus, Phillis’ critics failed to recognize the artifice of eighteenth century poetry and have not seen the competent craftsmanship of her poems. Saunders Redding also criticized Phillis in a scathing essay on her, saying that though the Wheatleys had adopted her, she turned round to adopt their terrific New England conscience. He contended that Phillis’ conception of the after-life was different from that of most of the slaves as found expressed in songs and spirituals. I find Redding’s accusations to be so instructive for an understanding of the mindset of the first-level audience that I will bring up more of it to illustrate my claim that with such a disposition, this audience (represented by the likes of Redding) has failed to do a deeper reading of Phillis. My stance is buttressed by evidence from these critics themselves. Their penchant for belittling the potency of Phillis’ works leaves room for much to be desired. Let’s turn to one clear evidence of such a wrongheaded criticism. Redding says that “the extent to which she was attached spiritually and emotionally to the slave is even slighter than the 5 extent she felt herself a Negro poet” (Black Literature Criticism, 1890). He goes on to make the most outrageous point when he describes her as “chilly,” and that part of that chill came from the influence of Pope on her. Certainly, this viewpoint is poisonous and cannot stand the test of scrutiny. It crumbles in the face of facts. The preponderance of feeling, movement, and action in Phillis’ works is obviously antithetical to any attribution of “chill” to her. Her use of powerful imagery and language to paint clear pictures in the reader’s mind about the obnoxious goings-on and her persistent call for protest, revenge, and change denote a hotblooded feeling and not a numbing chill. Her words are like swords, cutting through the mounds of butter. Through her manipulation of genres, she is able to protest strongly against the hypocrisy and slavery of White America without being scathed. Much use of the imperative and plosives creates tension in her works that runs counter to the chill that Redding attributes to her. More evidence can be adduced from other sources to debunk the critics’ stance. In her short biography of Phillis in Memoir (1834), Margaretta Odell praises Phillis, saying that as a young girl, she took to poetry as ducks take to water. She notes that although people encouraged her to read and write, “nothing was forced upon her, nothing was suggested, or placed before her as a lure; her literacy efforts were altogether the natural workings of her own mind” (Black Literature Criticism, 1891). According to Odell, Phillis was visited by visions in the night, which awakened her and which she wrote down as poems. “The next morning, she could not remember these dreams which had inspired her to write poetry.” How does one reconcile this biographical evidence here 6 with what Phillis’ critics accuse her of doing – exchanging her conscience with those of her White enslavers? Contrary to what her critics say, abundant evidence in Phillis’ poetry suggests that she uses her poetry to do all that they have failed to acknowledge. Perhaps, her rhetorical project is too complex for them to grasp or that they just cannot do any deeper reading without their lenses of racial prejudice. A few examples will suffice here. In driving home her arguments against slavery and other moral or religious atrocities that her poetry addresses, Phillis couches her call for freedom, order, power, and vengeance in a language that is heavily laden with irony, ambiguity, and mythological allusions that an ordinary reading cannot expose. Her powerful imagery to that effect pervades almost all her works – the elegies, pastoral, and odes – and it needs the subterranean reading of the second category of audience to grasp. I will now turn to three of her poems for evidence to reinforce my claims. In “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State of North America and C,” Phillis demonstrates her strong awareness of the position of her race under slavery and articulates it cleverly. She employs a rhetorical strategy that belies her real intent, using her persona (imagined self) for rhetorical persuasion. First, she opens her poem with 14 lines of congratulations: HAIL, happy day, when, smiling like the morn… Dartmouth, congratulates thy blissful sway:… While in thine hand with pleasure we behold The silken reins, and Freedom’s charms unfold… Then, in the next five lines, she does something else when she pleads to Dartmouth to protect and preserve the rights of Americans, vis-à-vis England, in the New World. She reinforces her plea by deviating from the conventional heroic couplet to use a triplet: 7 No more, America, in mournful strain Of wrongs, and grievance unredressed complain, No longer shall thou dread the iron chain… (lines 15-17) Her reference to “iron chain” should condition the careful reader’s mind to expect something more forceful, and this something is couched in the italicized “Tyranny” and the succeeding “lawless hand” and “enslave.” She is subtly protesting against slavery. Suddenly, Phillis plunges into a frontal attack on Dartmouth’s conscience as she uses the next stanza to establish her bitterness against slavery. She mentions “Freedom” and her ancestry (“Afric’s fancy’d happy seat”) directly. Here, she makes an analogy between America’s situation and her own: I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast? Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d: Such, such my case. And can I then but pray Others may never feel tyrannic sway? (lines 24-31) This part of her poem is significant for several reasons. Not only does Phillis use it to recollect her ancestry and the excruciating experiences of the Middle Passage, but she also creates an ambiguity that has continued to astound her readers. What does “Afric’s fancy’d happy seat” mean? How about the last line (“Others may never feel tyrannic sway”?) Her critics have pointed out that by referring to “Afric’s fancy’d happy seat,” Phillis did not believe either in the cruelty of the fate that had dragged thousands of her race into slavery in America nor in the happiness of their former freedom in Africa. The operative word used for this interpretation is “fancy’d,” which the critics claim to be synonymous to “delusory,” indicating that Phillis did not find anything concrete about any kind of freedom that might be thought as prevailing in her life before her 8 enslavement. In other words, Africa had no freedom to offer her unlike what she had been ushered into in Boston. This view of the critics is untenable, given the fact that the eighteenth century interpretation of “fancy” goes beyond “delusion” or “extravagance of imagination,” which then becomes a “false belief.” In its usage, the word meant that part of the mind that makes images, which in turn have their origin in sense experience (evidence from Dr. Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary definition and usage). Both “imagination” and “fancy” were used interchangeably and placed in the context of the mind’s ability to perceive a truth beyond its own immediate experience (Black Literature Criticism, 1892). In this poem, therefore, what Phillis intends “Afric’s fancy’d happy seat” to do is simple: to paint the picture of Africa as a fruitful paradise, a picture that was common to poets and others who had used their imaginative abilities to conjecture the continent, not as the “dark” one but as one that was natural and composed of rich soil and vegetation just like the Garden of Eden. By using that phrase, therefore, she is not discrediting her ancestry nor does she intend to shirk her heritage by that usage. It is noteworthy that Phillis uses this idea entailed by “fancy’d” in “On Imagination” and the poem to the Navy Officer, Rochfort (“Phillis’ Reply to the Answer”), part of which I reproduce below for illustration: And pleasing Gambia on my soul returns, With native grace in spring’s luxuriant reign, Smiles the gay mead, and Eden blooms again,… Just are thy views of Afric’s blissful plain, On the warm limits of the land and main.” (lines 21-34) As the poem moves away from this stage, we see Phillis returning to the persuasive mode once again when she commits Dartmouth to God’s care. By taking the issue to this level, she complicates matters for the superficial reader. A deeper reading 9 will show that Phillis is using the pathos of her own past to persuade Dartmouth to assuage the wrongs done to the Americans by the British and by implication, to extend the same dispensation to the enslaved Africans. What we have here is the poetry of argument, not one of self-expression or elegance. In assessing Phillis’ verse in terms of race, politics, and religion, Robinson (1975) brings up issues that support my stance. He does so in the context of Phillis’ life and works in his attempt to dispel long-standing critical arguments that her poetry falls short as literature and that she lacked self-awareness as an African American woman. He says this particular poem (“To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State of North America and C”) is comparable in excellence and intention to some of the great poems of the Restoration and the eighteenth century, especially, “Absalom and Achitophel,” Pope’s “An Essay on Man,” and “An Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot” (Black Literature Criticism, 1891). I have no qualms against that comparison for as long as it seeks to bring out the complexity of Phillis’ work that needs more attention than the cursory and dismissive approach that her critics are wont to adopt in trying to read her poetry. They are so eager to downgrade her that they fail to see her use of the rhetorical project to protest against the wrong deeds of the enslavers. Let’s see how Phillis does the manipulation of the rhetorical situation in another poem (“To the University of Cambridge, in New England”) in which she urges the students of Harvard to eschew profligacy. This poem has a didactic twist in addition to its rhetorical purpose to draw a distinction between races and to moralize for their differences to be acknowledged and accepted. Phillis’ strategy here is rhetorically useful. She creates an ironic contrast between herself (from “those dark lands” that knew nothing 10 about Christianity or the White people’s understanding of civilization) and the Harvard students (Christians by birth who had privileges of class and were offered knowledge of the highest civilization attainable by humanity). She is no doubt forcing us to see the abuses – what was denied her and her race. From an appeal to their religious sentiments through direct references to Jesus’ sacrificial works and the dangers of sin, she reminds them (and us) not to do what will destroy them (us). There is more to this interpretation, though. Robinson reads an archetypal situation into this poem, in which Phillis sets herself apart as an “Ethiop” who knows that she is nowhere near her immediate audience in social status but chooses to teach them the lessons of life. Thus, like the Roman slave in antiquity who stands behind the general marching triumphantly into Rome and who whispers into his ear that he is mortal, we see that the simple “savage” knows more than the sophisticated Harvard students. In another complex poem (“On Being Brought from Africa to America”), Phillis demonstrates her rhetorical prowess. She begins this eight-line poem by celebrating God’s mercy in bringing her from the “Pagan land” to the New World, and immediately creates the complexity that astounds the reader. How are we to interpret her words? Denotatively to mean that she was condemning her heritage and, therefore, exemplifying her “white mind”? Or connotatively (which is what a reading of literature entails) to point to the fact that she is speaking with her tongue in the cheek?: “T was mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought or knew. (lines 1-4) 11 The situation she creates here is profound. She uses ironic contrast again and goes further to attack the mentality of the enslavers. Didactic as her purpose is, Phillis uses this ironic contrast to teach the lesson she intends in the remaining four lines, where her direct references to race and the imagery contained in the Biblical Cain, refinement, and “th’ angelic train” paint the picture clearly that she is against slavery. She accentuates this hatred through the use of the imperative – “ Remember!” – leaving no doubt in the careful reader’s mind that she is in full control of her elements and is nobody’s derivative. What may baffle the reader is how she could find the courage to command a white readership that she knew were the enslavers. Through her rhetorical project, she never ceases to call the reader’s attention to the inequality between her status (as a slave but mentally free) and that of her enslavers (physically and materially free but morally enslaved). She frequently refers to “power” and seeks to command it in her works (using the rhetorical project for that purpose) though it was denied her physically. I daresay that her poetic powers knew no earthly authority to succumb to. In this eight-line poem (“On Being Brought from Africa to America”), there is emphasis, which is achieved with the italicized words. By alluding to Cain, the poet introduces an important issue: a false analogy of white superiority. She serves notice here that all human beings – whether white or black – need to be “refin’d” before they can “join th’ angelic train.” There is a quiet irony here as she uses her own race to push her argument. If she, the “unletter’d Afric,” could know that truth, why not the White Christians too? 12 Scholars have made connections between what Phillis is doing here and the quiet irony of Pope’s “lo, the poor indian” in his “An Essay on Man,” where civilized man thinks himself superior to the naïve savage whose conception of the after-life is unimaginative (Black Literature Criticism, 1892). For the “poor indian,” Heaven is simply a place where “No friends torment, no Christians thirst for Gold.” Yet, it is this very simplicity which serves as a satiric comment on the actual behavior of those people who call themselves “Christians.” It is obvious that by placing her imagined self in ironic juxtaposition of the “Christians” who would view her as “diabolic,” Phillis is making the same satiric point. She is adept at manipulating the imagined self for the sake of argument and not just setting out to mirror Pope. Her rhetorical project is unique and deserves more attention than her critics are willing to give her. It is a rhetorical project derived from inclusionary rhetoric – not to assign blame openly – but to use the jeremiad and a manipulation of tone, imagery, and literary form to protest against the goings-on. Using the pulpit oratory, verse epistle, and sermonic techniques, she succeeds in pressing home her protestations without being brutalized by White America. Her appeal to the religious sentiments of her audience is also part of the rhetoric of her poetry whose real effect a cursory reading will not expose. When she turns the searchlight on her inward (inner) self, especially in the poems that her critics see as “abstractions” (“To Maecenas,” “On Imagination,” “On Virtue,” “Thoughts on the Works of Providence,” “On Liberty and Peace,” and “An Elegy on Leaving”), we see a different Phillis – someone who could soar above ordinariness into the sublime mode, creating different worlds and making deep connections between the natural and the supernatural. We need to know more about her make-up to be able to 13 fully grasp her worth. This effort demands a revolution in the techniques for teaching and learning Phillis. My exploratory survey of Phillis’ poetry reveals certain implications for pedagogy about her life and works: Given the complexity of her poetry and rhetorical project, reading her effectively is a difficult task. Being the first African American woman to publish a book of poems and being the pacesetter of the elegiac mode (20 of the 46 poems published in her lifetime being about death), what should pedagogy do to restore her to her glory as a literary figure? It is at this point that I establish some mechanisms for the teaching and learning of Phillis Wheatley. Our students need to become informed members of the second group of readership to be able to debunk convincingly with evidence the wrongheaded criticism of Phillis that has threatened to overshadow her actual contributions to American (and world) literature. Let us first recall what Benjamin Brawley reports: that before 1840, a dozen editions of her poems were issued (including those in 1793, 1802, and 1816) and that after Margaretta Odell’s memoir of Phillis in 1834, there was demand for the book and two more editions were called for within four years. Additionally, some of the pieces found their way into school readers. This point is interesting because it tells us that attempts were made in the past to make Phillis known in the curriculum. But has the negative propaganda against her lessened through teaching and learning? Let us not forget her historical importance. The abolitionists cited her as proof of the Negro’s powers. Thus, Phillis has a kind of historical importance far beyond what her critics might see the intrinsic merit of her verses as warranting. How much do in our pedagogy to teach Phillis such that we could help bring out her true worth? 14 Angelene Jamison gives us a good point when she says that Phillis “was a poet who happened to be Black and it is a mistake to refer to her as a Black poet,” though she also discredits Phillis elsewhere. Teaching Phillis against this background means that we should do a close contextualization of her works to bring out their proper political reverberations, racial undertones, and outright manipulation of language for effect. Using the technique of cognitive poetics should be appropriate for this purpose. In this regard, there is need for a close marking of her entire rhetorical project – imagery, diction, meter, and genres – so that the background and foreground features can emerge to give us a clear picture about her. How about her works illustrating the pietas (patriotism)? An assignment that invites students to map the imageries will help break the jinx about the persistent claim by her critics that she was a mere imitator of Pope. One issue to address is how she could combine several genres in her poetry (the ode, elegy, pastoral, and romantic modes) to be able to embark on her rhetorical project without creating room for anybody to suspect her of rabble-rousing through her poetry. In “An Elegy on Leaving,” she combines the elegiac mode with the pastoral and the romantic. How she could use her poetry to fight for freedom without betraying her cause to her enslavers is worth probing. Erkilla (1993) reports that when Phillis’ book was published, “there was widespread fear of slave revolt; and that Abigail Adams’ September 1774 letter to John on the conspiracy of Boston Negroes is only one of a number of signs that fear of slave insurrection was spreading from the South to New England” (231). Does this evidence not debunk the criticism that attributes “chill” to her? If we want to do any deep teaching and learning of Phillis’ works, we must revisit the peculiar circumstances under which she lived and worked for ideas with which to 15 appreciate what we read. It is my contention that any reading of Phillis that does not place the constraints under which she lived and worked in the historical context (of literary works, slavery, Puritan Christian worldview, etc.) will be shoddy. Those who rush to consign Phillis to the back rows of intellectual and literary endeavors had better rethink their approach because she is larger than the space they have carved to place her in. She will not fit in there. One important question that must guide any teaching of Phillis is: Why was Phillis hailed by London’s literati if she was a mere derivative of the neoclassical literary tradition of Pope? An assignment should focus on a selection of poems by both authors for comparison and contrast. The Pope-Phillis study in the art of the heroic couplet should be interesting. At the outset, it will reveal how original Phillis is, coming out with the use of the triplet to inject emphasis into portions of her poetry where she does her own thing – a skill that is devoid from Pope’s poetry. It is compelling to see how Phillis devices this rhetorical strategy. Recognizing her worth would, then, emerge as an appropriate reaction just like the London literati did to establish that their fascination for Phillis was not adventitious (or an impulsive outburst of misplaced sentiments) but was the direct upshot of her stature as a “natural genius.” A lesson from Joseph Addison will serve a useful purpose in this vein. It relates to the eighteenth century aesthetic taste that borders on the love for “natural genius” - a taste that derived from the Latin aphorism that “poeta nascitur, non fit,” meaning that says: “a poet is born and not made” (BLC, 1891). In his writing in 1771 (Spectator, 160), Addison distinguished two kinds of poetic genius: those artists “who by the mere strength of natural parts, and without any assistance of art or learning, have produced works that were the delight of their own 16 times and the wonder of posterity” (which I conceive Phillis to be); and artists who “have formed themselves by rules and submitted the greatness of their natural talents to the corrections and restraints of art” (which, to me, Phillis is not). Though Addison never imagined this term to be applied to a working-class poet, by mid-century, the term was given a distinctly democratic twist and the “mute, inglorious Miltons” emerged. These were the poor who, if only given the chance, would burst forth in glorious song (poetry). These “unlettered” poets were patronized by people of position. That the Countess of Huntingdon patronized Phillis’ work was not an isolated case. The records show that the nobility supported such geniuses. For example, Joseph Spence sponsored Stephen Duck, the “Thresher-Poet;” William Shenstone, Lady Montague, and Lord Lyttelton encouraged James Woodhouse, the “Shoemaker Poet;” Lord Chesterfield helped Henry Jones, the “Bricklayer Poet;” and Hannah Moore patronized Ann Yearsley, the poet known as Lactilla, the “Milkmaid-Poet,” (Black Literature Criticism, 1891). This historical account is important because it gives us the tool with which to appreciate Phillis’ limitations as an “unlettered muse” and how to approach a deep reading and interpretation of her poetry. The historical circumstances under which she worked must also be addressed. For example, James Weldon Johnson claims that her mind was steeped in the classics, citing as examples, the fact that her verses are filled with classical and mythological allusions, her knowledge of Ovid, Latin authors, and Alexander Pope. What should we do with such a claim? Other claims draw attention to the peculiarities of Phillis’ circumstances in which she was reared and sheltered in the wealthy and cultured Boston family of the Wheatleys, never had the opportunity to learn life nor did she get the chance to find out 17 her true relation to life and to her surroundings. No one refutes the fact that Phillis was denied physical contact with the people of her African race, though she communicated with Obour Tanner. More pathetically, she died at only 31. These factors had their own implications for Phillis and gave her a unique identity as a poet. Thus, when we teach her works, it is imperative that we bring such historical happenings to bear on our techniques for ours students to know where she belongs. She cannot be divorced from those happenings and viewed in isolation as if all she has to recommend her is her “race” and “social status.” I contend that any reading of her that turns the searchlight on her origin and social status will be misguided. On how to analyze the language of her works, we have a huge responsibility to appreciate what Phillis achieved in less than 31 years. From Odell’s Memoir, we lean that she never had any “grammatical instructor or knowledge of the structure or idiom of the English language, except which she imbibed from a perusal of the best English authors and from mingling in polite circles…” (BLC, 1892). But the quality of language use in her works is high and she achieves effect through her diction. We need to extend the Phillis Wheatley curriculum to cover a study of her linguistic repertoire too. Analyzing her use of language alone should inform the reader about the power behind her works. She uses the imperative often and makes brazen statements that anybody with the kind of mentality ascribed to her by her critics couldn’t have done, given the circumstances under which the writing was being done. She adroitly uses the word “winter” in “On Imagination” to refer to the white folks whose activities threatened the wellbeing of her race and could have been punished for heresy had her readers been 18 serious enough to read a deeper meaning into these two lines in the same poem quoted above in which she virtually “crowns” imagination: Such is thy pow’r, nor are thine orders vain, O thou the leader of the mental train… (lines 33 and 34) In “To Maecenas” too, Phillis’ use of language drives along her rhetorical project. We see in lines 14 and 15, where she uses monosyllables; we see how her she paints a picture of movement before plunging into the liquid and trisyllabic long vowels that show a more rapid movement in: “The lenth’ning line moves languishing along” (line 16). An effective pedagogy must relate to this advice from James Weldon Johnson: “Wheatley’s work must not be judged by the work and standards of a later day, but by the work and standards of her own day and her own contemporaries…” (1880). According to him, then, by this method of criticism, one will see that “Wheatley stands out as one of the important characters in the making of American literature, without any allowances for her sex or her antecedents.” A Phillis Wheatley curriculum must involve more than a mere reading of her works in isolation. Their relevance to the search for the intricacies of the entire gamut of American (and not only African American) literary tradition must be analyzed through a comparative study of the literature of the period. Furthermore, any attempt to teach Phillis Wheatley successfully must begin with an understanding of the agenda of her critics. How does one counteract their criticism, which derives not from an unprejudiced reading of her works (style, themes, and concerns – her entire rhetorical project) but from their use of lenses tainted with prejudice against her race and social status? We need to understand the mindset of the critics themselves and to use appropriate scholarly endeavors to counteract their unproductive criticisms. For example, it will be instructive to interrogate thoroughly a statement from 19 Angelene Jamison that “…in any literary analysis of the poetry of Phillis Wheatley from a Black perspective, we must accept the fact that her poetry is the product of a white mind, a mind that had been so engulfed in the education, religion, values, and the freedom of Whites that she expressed no strong sentiments for those who had been cast into the wretchedness of slavery by those she so often praised with her pen…” (408-16). What this statement can do to sustain the anti-Phillis sentiment is obvious. We cannot accept it without fighting back to debunk it with evidence from Phillis’ works. Her poetry and prose are available for us to study careful for the much-needed evidence. In this claim, Jamison is drawing attention to what she calls a “fact” about Phillis’ conscience without any proof as if it is easy for one to swap one’s conscience (an innate quality) with that of another person. The implications of such spurious readings of Phillis to pedagogy cannot be lost on an astute reader. Jamison’s position must be clear by now when she says that “any student who is exposed to Phillis Wheatley must be able to recognize that her poetry expressed the sentiments of eighteenth century Whites because her mind was controlled by them, her actions were controlled by them, and consequently her pen” (BLC, 1890). Certainly, this criticism is without any foundation in reality because Phillis has proved to be anything but what her critics want us to believe. One major area in which Phillis will be remembered is her attention to the sublime, which is engendered in her poetry by her constant use of the imagery of movement to lofty heights of sense experiences through imagination. Her poems on abstractions (“To Maecenas,” “On Virtue,” “On Imagination,” “On Recollection,” and “Thoughts on the Works of Providence”) demonstrate her attainment of the sublime, which is peculiarly hers and not Pope’s. We see her use of the sublime as a vehicle for 20 initiating the desire to see death as an escape from the ills of the society and many other situations that the imagination could dredge up. Her differentiation of “imagination” from “fancy” is obvious as she lifts the former above the latter and establishes how to use those faculties. It is in this area that her critics attempt reinforcing their criticism of her as a derivative of Pope. No serious reader of Phillis will agree with the stance of her critics because she establishes clearly her own identity as a “natural genius” in the pursuit of the sublime and achieves it without recourse to anybody’s style. I expect assignments on the subject of “the sublime” to give students a better opportunity to know the uniqueness of Phillis’ poetry. Perhaps, the time has come for me to make an emphatic statement here to reinforce my stance. The time has come for us to understand that Phillis Wheatley’s works have their intrinsic good qualities that can be appreciated without necessarily being read through the lenses of race and social status. In this paper, I have argued that the rhetorical project under which Phillis wrote her poems and prose is so complex as to defy any meaningful interpretation through superficial reading. What Phillis’ works suggest is that the strategy to be used to read her must agree with the complexity of her works. Anything short of that systematic conceptualization will not help an effective reading of her works. 21 References Draper, James P. (ed.) Black Literature Criticism: Excerpts from Criticism of the Most Significant Works of Black Authors over the Past 200 Years. Vo;. 3. MarshallYoung. Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1992. Erkilla, Betsy. “Phillis Wheatley and the Black American Revolution.” In A Mixed Race: Ethnicity in Early America. Frank Shuffleton (Ed.). New York: Oxford UP, 1993. pp. 225-40. Loggins, Vernon. “The Beginnings of Negro Authorship, 1760-1790.” In his The Negro Author: His Development in America to 1900, 1931. Reprint by Kennikat Press, Inc. 1964. pp. 1-47. Odell, Margaretta Matilda. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley: A Native-African and a Slave. 3rd ed. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838, p. 155. Richmond, M.A. “The Critics,.” In his Bid the Vassal Soar: Interpretive Essays on the Life and Poetry of Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753-1784) and George Moses Horton (ca. 1797-1883). Washington, DC.: Howard UP, 1974. pp. 53-66. Robinson, William H. Phillis Wheatley in the Black American Beginnings. Detroit: Broadside Press, 1975, 95pp. Scruggs, Charles. “Phillis Wheatley and the Poetical Legacy of Eighteenth-Century England.” In Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, vol. 10, 1981. pp. 279-95. 22