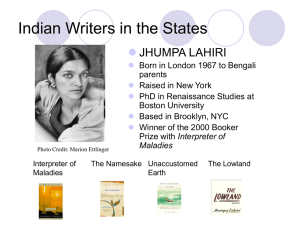

FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS IN JHUMPA LAHIRI'S THE NAMESAKE

advertisement