Fashion & Fancy in New York: The American Monarchs

advertisement

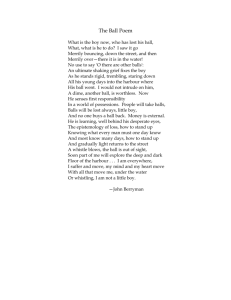

Fashion & Fancy in New York: The American Monarchs. Emilia Müller Abstract. This presentation explores the fancy dress worn by New York’s high society during the Gilded Age. Trough the analysis of Jose Maria Mora’s photographic collection of the guests who attended two of the most well-known fancy dress balls from this era; the Vanderbilt Ball and Bradley-Martin Ball, plus the study of contemporary English manuals that advised what to wear at these balls, I distinguish which were the fashionable fancy costumes, and acknowledge the main visual and written references behind those fantastical sartorial decisions. My thesis suggests that no matter how respectable these events became in late nineteenth century, fancy dresses and their symbolic representations were still able to transgress boundaries related to class, gender and race. This research will not only address these fancy dress balls beyond their common and limited description as conspicuous social events of New York’s upper class society, but will also interpret the chosen fancy costumes and their personifications as expressions of the elite’s relation to political, cultural and social phenomena of the period. In the selected portraits of the fancy dresses, I aim to discover hidden anxieties and expectations shared by this selfconscious group concerning its complex relationship with the European aristocracy. As female guests included authentic royal regalia in their representations of noble women of the Old World, their costumes went beyond the conventions of fancy dress' artificial nature. Through the confusion of reality, high class New Yorkers acquired a noble past that only existed through sartorial fantasy, expressing the hysterical need to overcome the lack of real blue blood in their veins. As fancy costumes’ metamorphic ability has been commonly disregarded by dress historians, this presentation advocates for its relevance in the study of fashion and in the configuration of social and cultural identities. Introduction. In late nineteenth-century New York it was a fashionable trend for high society to organize and attend fancy dress balls. These luxurious events that imitated a European way of sociability became memorable social gatherings, promoted by the wealthy families of the Gilded Age. These parties were different from any other events in their busy social calendars, because costume balls meant wearing lavish fancy dresses, no less expensive and elegant than the most fashionable garments of the period. These opulent occasions became the perfect opportunity for a conscious display of prosperity of those who stood at the top of the social ladder, a small but select group which had made their fortunes building corporate empires in the era following the Civil War. Those chosen families were considered the accepted leaders of America’s selfproclaimed aristocratic society, and they ambitiously tried to resemble the privileged European classes in every aspect of their social and cultural agendas, including the celebration of these splendid fancy dress balls. 1 The most well-known and controversial costume balls of the era, the Vanderbilt Ball and the Bradley Martin Ball recreated the exclusiveness and luxuriousness of French and English court assemblies of the ancien regime1, and were quite different from the collective dressing up of the past century. As Cynthia Cooper explains, The fashion for fancy dress balls grew over the course of the nineteenth-century after a shift in social mores at the ends of the eighteenth-century had made masquerade balls and parties seem licentious. Private costume parties, where no masks were worn, became known as “fancy balls”.2 While in the beginning of the century, upper class social events were just “small, enjoyable affairs, without any attempt at unusual display”3, in the last quarter, these gatherings became conspicuous opportunities for opulence and spectacle; the ball evolved from “a shabby grub to a brilliant chrysalis.”4 In postbellum America, wealthy New Yorkers planned fancy dress balls for commemorations and special events in their newly built mansions, but also in New York’s fashionable and exclusive restaurants such as Delmonico’s, Sherry’s, and the Waldorf Hotel later in the century. Although these parties were originally copied from European court society, eventually private costume balls became hallmarks of New York high society’s leisure time as they tested the elite’s ability to promote and afford such impressive entertainments, reaffirming their privileged status and an adequate exhibition of genteel social conduct. High society cherished costume balls because of their playful requirements, and every detail was thoroughly calculated, especially the designs of the fanciful gowns. At fancy dress balls, the guests had the chance to transform themselves through their costumes in characters they were not in real life, thus playing with their appearances and identities as they wished, at least for one night. However, these had to be respectable private entertainments and followed certain rules and an established order; only a chosen group of people were invited, America’s rich and privileged, and the costumes had to be fashionable and never too creative, other guests had to always discern what those fantastically clad bodies were impersonating. Besides these formalities, I aim to suggest that no matter how decorous these events were in late nineteenthcentury New York, fancy dresses and their symbolic representations were still able to transgress 11. Simon, Fashion in Art, 33. 22. Cooper, Magnificent Entertainments, 21. 33. “Current Literature”, Philadelphia Times, 1889, 391. 44. Ibid. 2 established boundaries related to class, gender and race. This presentation will not only address the Vanderbilt and the Bradley Martin celebrations beyond their common and limited description as conspicuous social events of New York’s upper class, but will analyze the chosen fancy costumes as expressions of the elite’s relation to political, cultural and social phenomenon of the period. This presentation studies fancy dress balls in the context of late nineteenth-century New York’s intense economic and cultural changes, and the consequences these transformations brought to the city’s social configuration. Because of massive immigration and an extreme labor explosion, costume balls, and their inherent intentions of disguise, will become complex expressions of a society in constant tension. As argued by Esther F. Romeyn, ...economic growth, and unprecedented rate of social mobility, and the rise of commodity culture made the tools and attributes of middle-class identity available to groups for whom the possible extent of self-fashioning had previously been more or less restricted.5 The metropolis became a large urban theater, where avid newcomers could easily learn through etiquette manuals and city guidebooks every aspect of the daily life of the upper classes. The idea of dressing like someone different from yourself, in this case as a member of the higher classes became an easy task thanks to the development of mass production and ready-to-wear clothes that consequently blurred the existing sartorial differentiations between social classes. Under these circumstances, clothes attained the dangerous quality of being able to hide or transform the authentic social identity of the wearer. So, if the streets of the emerging modern city already constituted a scenario filled with characters in disguise, with the ambition of transforming themselves superficially, the costume ball develops as an exaggerated continuation of this masquerading game. Paradoxically, in these fancy dress balls, it will be the higher-classes, the prominent members of New York society that will take advantage of the fantastical dresses and alter their everyday selves. High class costume balls were comprehensively described in newspapers and magazines, detailed articles included the names and some photographs of the guests in their fanciful characters, as well as the decorations, choreographies and menus chosen for the special night. Because of this, these supposedly exclusive social gatherings became open spectacles for a wider public.6 This collective voyeurism of the upper classes, encouraged by the emergence of a 55. Romeyn, My other, My self, 5. 66. Montgomery, Displaying Women, 48. 3 “society journalism” in the 1880s had important social connotations. As established by Montgomery, ‘Wealthy New Yorkers advertised their wealth and performed class acts in laying claim to high social status. Putting themselves on display and into circulation was an essential part of asserting and maintaining this claim.7 José María Mora, author of most of the photographs selected for this presentation, became a well-known photographer thanks to the craze that develop in the late nineteenth-century for the collecting of celebrity pictures. 8. As a market for images of women at the highest level of American society developed later in the century, studio photographers like Mora began to call themselves “society photographers” and became essential features in high society events. The interest in being photographed in fancy dress reveals the great importance guests attributed to their sartorial transformation. To negate the idea of Cinderella’s “one night only”, the ephemeral magic was somehow captured for eternity, and displayed for those excluded from the party. Because this kind of journalism spread throughout the entire country chronicling the life of New York’s upper class, and the studio portrait was no longer an attribute of the wealthy, a wider imitation of the elite became easier and in consequence, according to Homberger, “aristocracy was demystified.”9 Under these circumstances, the portraits of New York’s elite in pretentious and costly fancy dresses, symbolized a deeper effort in maintaining a certain inimitability with the lower classes. These pictures were not like other studio photographs, these were images of old Renaissance kings and queens, magical creatures, exotic odalisques and peoples from foreign countries, this was not just a sartorial game but a actual performance of difference. The American monarchs. As the majority of the fancy dresses worn at the Vanderbilt and Bradley Martin balls have not survived the test of time, the costume photographic collection constitutes itself as the most fundamental testimony in the exploration of these fantastical garments. 10 These portraits in their inexorable black and white limited dimensionality, are the only sources of the visual transformations of the guests and clearly evidence the dedication and great importance New 77. Ibid., 122. 88. Schweitzer, The Mad Search for Beauty, 259 99. Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York, 203 1010. Some exceptions are two dresses in the Textile and Costume Collection of the Museum of the City of New York: Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt dress of “Electric Light” worn at the Vanderbilt Ball in 1883 and Mrs. Elliot F. Shepard “Marquise” costume worn at the Bradley Martin Ball in 1897. 4 Yorkers attributed to these fashionable amusements. Each portrait encloses a miniature theatre, where the subjects exhibit a silent but nevertheless compelling sartorial monologue evoking a fabricated time and space different from that of Gilded Age New York. Its ambiguous authenticity is conveyed by the expected accuracy of the costumes and of the surrounding constructed props and architectural landscapes provided by the photographer.11 Some guests even take recognizable bodily attitudes of the characters they are impersonating, thus heightening the sense of reality. These pictures denote the possibility of escapism from the self, as the artificial appearances provoke the total alteration of fixed identities, and a former reality is utterly confused in the supposed objectivity of the photographic media. Although the garments did not hide faces or promote subversive cross-gendered bodies, each layer of fancy costume still conjured alterity and disruption from the historical present, and “the true self remained elusive and inaccessible, illegible, within its fantastical encasements”.12 Costume balls depended purely on the visual impact of the fancy dresss, it was only through them that the party could achieve its expected unique essence. In late nineteenth-century costume balls some characters were more fashionable and ubiquitous than others, especially those that represented European nobility from the past. Those attending New York's fancy dress balls conspicuously favoured the portrayal of royalty, and court figures from the Renaissance until early nineteenth-century. At the Bradley Martin’s Ball there were more than fifty women clad as Marie Antoinette, whereas for the Vanderbilt Ball no less than twenty men chose to personify “Louis XVI”.13 Not only the French court was a favoured theme for the invited, but its British counterpart was also represented, most predominantly by monarchs such as “Queen Elizabeth”, “Henry VIII”, and noblemen like the “Duke of Sussex”. At her ball, Cornelia Bradley was fully dressed as “Mary Queen of Scots”, and in order to capture the splendour of her regal essence, Mrs. Bradley covered herself in jewels that had once belonged to the Empresses Marie Louise, Josephine, and Queen Marie 1111. Sometimes total accuracy was not possible. The The New York Times exposed a Louis XV using modern eyeglasses in the Bradley Martin Ball. “Bradley Martin Ball”, The New York Times, Feb. 11, 1897. 1212. Although the author refers to eighteenth-century costumes, the same idea can be applied for late nineteenth-century fancy dresses. Castle, Masquerade and Civilization, 5. 1313. Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 334. 5 Antoinette.14 Similarly, Alva Vanderbilt at her event, costumed as a “Venetian Renaissance Countess” based on a painting by the artist Alexander Cabanel,15 clad herself with a row of pearls that had been acquired from the collections of Catherine the Great and Empress Eugenie of France.16 This approach to the noble European past by New York’s economic elite compasses an interesting panorama, by including material evidence of royal regalia in the representations of these noble women, the costumes of the hostesses went beyond conventions of fancy dress’s artificial nature. These were false personifications that reunited true pieces of life. Moreover, it was commented by the press, “that the quality of people who have these rare and costly gems would never think of attending such a historic function in sham ornaments.”17 The adoption of real precious stones of the European monarchy not only confused ideas about authenticity and falsity in the fantastically clad body, but conceptions of time and history. By donning the jewels of various queens of different time periods simultaneously, the wearers were embodying a general conception of a female aristocracy with no chronological delimitations. As described by Montgomery, ‘European structures and aristocratic accoutrements (personal clothing, accessories) harking back to courtly societies were thus imported and adapted to the needs of a powerful, wealthy business elite attempting to impose its leadership by buying history.’18 These bourgeois women’s purchasing capacity, supplied by their husbands, allowed them to appropriate artefacts from the European royal past and intimately use and display them as expressions of their indisputable power as New York’s high society. This attachment to European nobility was not only metaphoric as insinuated by the royal fancy garments worn at the costume balls, but it was a constant preoccupation for New York’s haute bourgeoisie. The eagerness for legitimizing themselves as the economic ruling class instigated the upper class to emulate European aristocracies. New York’s imitativeness of the Old World19 became a means to acquire refinement and also allow the bourgeoisie ‘to anchor 1414. Mrs. Bradley Martin sent agents from Tiffany & Co. to Paris to buy Marie Antoinette’s jewels in an auction. Beard, After the Ball, 167. 1515. Hayden Rector, Alva, That Vanderbilt-Belmont Woman, 48. 1616.“In addition to the tiara, she wore a double dog collar of diamonds and rubies, a diamond pendant that had been part of a royal rosary, a cascade of diamonds in the form of a triple-decker brooch, a fourstand diamond stomacher, a necklace that fell over the breasts of the stomach, a lattice over bodice of small diamonds with larger diamonds with larger diamond pendants in some of the triangles, and Mme. de Sevigny’s diamond starburst brooch, which date to the court of Louis XIV. For security much of her jewelry was sewn to her dress.” Beard, After the Ball, 162. 1717. “The Bradley Martin Ball”. The New York Times, Feb. 9, 1897. 1818. Montgomery, Displaying Women, 65. 1919. “Americans as Money Spenders”, The New York Times, Feb. 21, 1897. 6 their new wealth in history and cultural achievement, and to set themselves apart from others.’20 By dressing up as royal figures such as “Henry IV”, “Marie Antoinette”, “Louis XV”, and as “French Marquises”, high society’s men and women were borrowing a foreign tradition, and at the same time, demonstrating a privileged knowledge of European historical and cultural heritage. As established by Harper’s Bazaar regarding Mrs. Bradley Martin’s Ball, ‘The history of costume is the history of the world, and no one can look into the business of getting up a fancy dress without stumbling over a great many most important historical facts.’21 European cultural expressions were conveyed in the portrayals of Shakespearean roles, eighteenth-century theatrical characters such as “Lady Teazle” from R. B. Sheridan’s play The School of Scandal, and figures from the French Operas La Perichole and Les Cloches de Corneville.22 (Fig. 15) These fancy dresses expressed the need to overcome the ‘lack of tradition, glamour, polish and culture’, a widespread opinion about the upper class in late nineteenth-century America.23 New York’s bourgeoisie cultivated itself by conspicuously spending their accumulated wealth imitating the exquisite lifestyle of European high society. They would afford the excursions of the Grand Tour and the purchasing of Parisian fashions and European art for their private galleries.24 But most importantly the upper classes had the financial means to acquire British noble titles through transatlantic marriages.25 Each of these desires is revealed in the visual and material language of the fancy dresses worn at the Vanderbilt and Bradley Martin balls. For example, the stylish House of Worth designed most of the fanciful garments in Paris and some of their inspirations came directly from European paintings that hung in New York’s gilded mansions. This was the case of W. H. Vanderbilt’s costume, which was a replica of the Duc de Guise in a painting by the French artist Albert Aublet from Vanderbilt’s own collection. 26 At the same time, the personifications of different nationalities and time periods present at these costume balls, evoked a pastiche of spaces and cultural realities encountered likewise in voyages abroad, while the use of kings and queens’ artificial attire embodied the pressures of this false aristocracy to legitimize its social position through the tangible connections with royal garments and artefacts. Hence, costume balls illustrated through their sartorial exhibitionism the tensions 2020. Sven Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 50. 2121. “The Bradley Martin Fancy Ball”, Harper’s Bazaar Magazine, Feb. 20, 1897. 2222. “All Society in Costume”, The New York Times, March 27, 1883. 2323. Stowe, Going Abroad, 5. 2424. “Mr. Vanderbilt’s Gallery”, The New York Times, Dec.10, 1885. 2525. Montgomery, Gilded Prostitution, 4. 2626. Churchill, The Upper Crust, 127. 7 and aspirations of New York’s bourgeoisie regarding their complex self-definition as a class. America’s nobility which ‘consisted of robber barons, merchant princes and copper kings’27 was considered ridiculous by the European aristocracies and questioned by New York’s lower and middle classes who condemned the excesses of the bourgeoisie economic and political power.28 Thus, for New York’s self appointed aristocracy, based on the wealth of the noveaux riches and the ancestry of the old Dutch families, the need to marry the nobility across the Atlantic, and gain the cultural and genealogical legitimacy they lacked, became of paramount importance.29 Playing to be royalty in fancy dress balls was not just a childish diversion but it affirmed the pressure and the longing to be incorporated in European aristocratic families. Through the harmless superficiality of the fancy dress the aspiration could be easily achieved without the real consequences of homesickness and cultural shock that these titled marriages sometimes brought upon American heiresses.30 However, the circulation of images of New York’s high society women clad in royal apparel through the press could have also contributed to the pejorative view of upper class women as ‘gilded prostitutes’ who, as defined by Montgomery, were criticized for marrying noble men only for ‘crude social ambition’.31 Ultimately, by assuming the role of European royalty through the most grandiose gowns, high society demonstrated its confidence and social supremacy in New York’s political and economic arena. In Beckert words, ‘By symbolically appropriating the once-towering social position of the French aristocracy, they made clear that it was they [the bourgeoisie] who now were at the pinnacle of society.’ 32 Maybe New York’s bourgeoisie didn’t have blue blood in its veins, but through consumption and fantasy the upper class momentarily changed history and became the most venerable and elegant of the American monarchs. Bibliography. 2727. Olian, The Gilded Age, 6. 2828. Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 325 2929. Ibid., 211. 3030. “During this period sixty American women married the holder of, or heir to, a hereditary titles.” Montgomery, Gilded Prostitution, 4. 3131. Ibid., 11. 32 Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 334. 8 Beard, Patricia, After the Ball: Gilded Age secrets, Boardroom Betrayals, and the Party that Ignited the Great Wall Street Scandal of 1905. New York: Harper Collins, 2003. Beckert, Sven, “The making of New York City’s Bourgeoisie, 1850-1886” PhD diss. Columbia University, 1995. _____. The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850-1896. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Castle, Terry, Masquerade and Civilization: the Carnivalesque in the Eighteenth Century English Culture and Fiction, Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1986. Churchill, Allen, The Upper Crust: and Informal History of New York’s Highest Society. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, 1970. Cooper, Cynthia, Magnificent Entertainments: Fancy Dress Balls of Canada’s Governor’s General, 1876-1898. Fredericton, N.B.; Hull, Quebec: Goose Lane Editions and Canadian Museum of civilization, 1997. Homberger, Eric, Mrs. Astor’s New York. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. Montgomery, Maureen E., Displaying Women: Spectacles of Leisure in Edith Wharton's New York. New York: Routledge, 1998. ______. Gilded Prostitution: Status, Money and Transatlantic Marriages, 1870-1914. London: New York: Routledge, 1989. Schweitzer, The Mad Search for Beauty: Actresses’s Testimonials, the Cosmetics industry, and the democratization of Beauty. In Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 4:3 (July 2005): 255-292. Simon, Marie, Fashion in Art: the Second Empire and Impressionism, London: New York, distributed in the USA and Canada by Antique Collector’s Club, 1995. Stowe, William W., Going abroad: European Travel in Nineteenth Century American culture. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994. Rector, Margaret Hayden, Alva, that Vanderbilt-Belmont Woman: Her story as she might have told it. Wickford, R.I.: Dutch Island Press, 1992. Romeyn, Esther F., My other/my self: Impersonation, Masquerade, and the Theater of Identity in turn-of-the-century New York City. (Thesis, (Ph.D.) University of Minnesota, 1998. Olian, Joanne, The House of Worth the Gilded Age, 1860-1914, New York: Museum of the city of New York, 1982. 9 “The Bradley Martin Ball”. The New York Times, Feb. 9, 1897. www.nytimes.com “Americans as Money Spenders”, The New York Times, Feb. 21, 1897. www.nytimes.com “All Society in Costume”, The New York Times, March 27, 1883. www.nytimes.com “Mr. Vanderbilt’s Gallery”, The New York Times, Dec.10, 1885. www.nytimes.com “Current Literature”, Philadelphia Times, New York, Nov. 1889, Vol. III, Iss. No. 5, p. 391. “The Bradley Martin Fancy Ball”, Harper’s Bazaar Magazine, February 20, 1897; 30, 8; American Series Online p. 147. 10