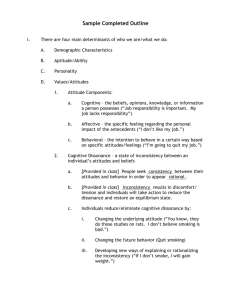

A Self-Standards Model of Cognitive Dissonance

advertisement