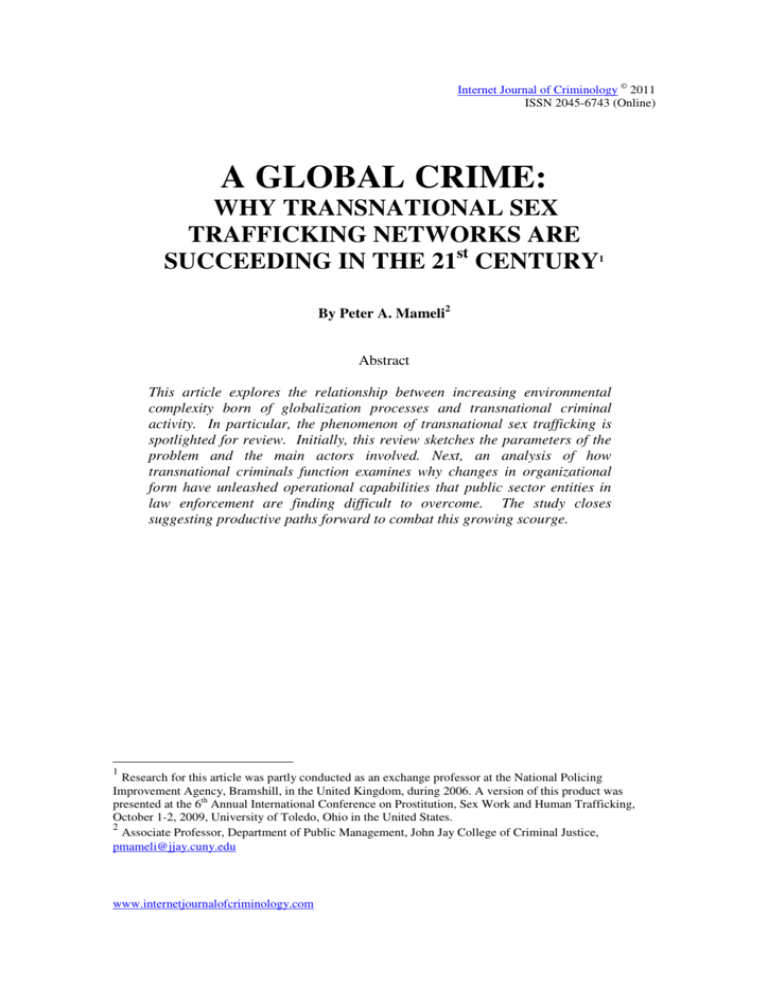

a global crime - The Internet Journal of Criminology

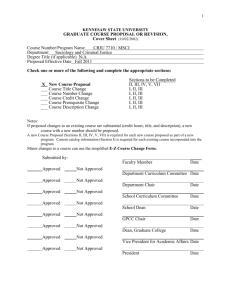

advertisement