The Danish Health Care System: An Analysis of Strengths

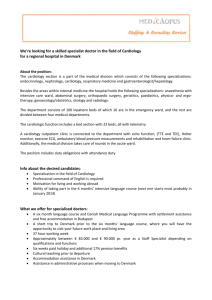

advertisement