SparkNotes is the only series of study guides written and produced

SparkNotes is the only series of study guides written and produced exclusively by Harvard students and graduates. Unlike guides sold in stores, SparkNotes are FREE, interactive, and available online any time.

Printed SparkNotes will never be as good as the real thing, so be sure to visit

SparkNotes.com to read the newest SparkNotes, chat with other readers, post a question, or send us your comments and requests. Enjoy!

-The SparkNotes Team

This SparkNote is the property of iTurf Inc. You may not copy, publish, or distribute it in any form other than for your own personal use without the express written consent of iTurf Inc.

Alice in Wonderland and Through the

Looking Glass

by Lewis Carroll

Writer

Brian Gatten

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Contents

List of SparkNotes.com Titles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

Characters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

Chapters 2-3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

Chapters 4-5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

Chapters 6-7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13

Chapters 8-10 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

Chapters 11-12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

Through the Looking Glass: Chapters 1-2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

Chapters 3-4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

Chapters 5-6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

Chapters 7-8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

Chapters 9-12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

Questions for Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

1

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

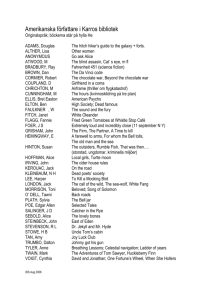

More Free Titles at SparkNotes.com

1984

Absalom, Absalom!

The Aeneid

Agamemnon

Alice in Wonderland

All the King’s Men

All Quiet on the Western Front

All’s Well That Ends Well

Anna Karenina

Animal Farm

Antigone

Antony and Cleopatra

The Apology

As I Lay Dying

As You Like It

The Awakening

The Bell Jar

Beloved

Beowulf

Billy Budd

Black Boy

Bless Me, Ultima

The Bluest Eye

Brave New World

The Call of the Wild

Candide

The Canterbury Tales

Catch-22

The Catcher in the Rye

The Color Purple

The Comedy of Errors

A Connecticut Yankee...

Crime and Punishment

The Crito

The Crucible

Cry, the Beloved Country

Cyrano de Bergerac

Daisy Miller

David Copperfield

Death of a Salesman

The Declaration of Independence

The Diary of Anne Frank

Doctor Faustus

A Doll’s House

Don Quixote

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Dr. Zhivago

Dracula

Dubliners

Emma

Ethan Frome

Ethics

Euthyphro

The Faerie Queene

Fahrenheit 451

A Farewell to Arms

The Fellowship of the Ring

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Frankenstein

Franny and Zooey

The Glass Menagerie

The Good Earth

The Grapes of Wrath

Great Expectations

The Great Gatsby

Gulliver’s Travels

Hamlet

The Handmaid’s Tale

Hard Times

Heart of Darkness

Henry IV Part 1

Henry IV Part 2

Henry V

The Hobbit

The House of Mirth

Huckleberry Finn

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

The Iliad

Dante’s Inferno

Invisible Man

Jane Eyre

The Joy Luck Club

Julius Caesar

The Jungle

Keats’s Odes

The Last of the Mohicans

King Lear

Light in August

Lolita

Lord of the Flies

Love’s Labour’s Lost

Macbeth

Madame Bovary

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Measure for Measure

Merchant of Venice

The Metamorphosis

Middlemarch

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Moby Dick

Mrs. Dalloway

Much Ado About Nothing

My Antonia

Narrative of... Frederick Douglass

Native Son

Night

Notes from Underground

The Odyssey

The Oedipus Trilogy

Of Mice and Men

The Old Man and the Sea

Oliver Twist

On the Road

The Once and Future King

One Day in the Life of Ivan...

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Othello

The Outsiders

Paradise Lost

Phaedo

The Plague

A Portrait of the Artist...

Pride and Prejudice

The Prince

The Red Badge of Courage

Plato’s Republic

A Raisin in the Sun

The Red Pony

Richard II

Richard III

Robinson Crusoe

Romeo and Juliet

A Room with a View

The Scarlet Letter

Second Treatise of Government

A Separate Peace

Shakespeare’s Sonnets

Silas Marner

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Sister Carrie

Slaughterhouse Five

Snow Falling on Cedars

Sons and Lovers

The Sound and the Fury

The Stranger

A Streetcar Named Desire

Sula

The Sun Also Rises

Twelfth Night

A Tale of Two Cities

The Taming of the Shrew

The Tempest

Tender is the Night

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Things Fall Apart

This Side of Paradise

Titus Andronicus

To Kill a Mockingbird

To the Lighthouse

Tom Sawyer

The Three Musketeers

Through the Looking Glass

Treasure Island

The Trial

The Turn of the Screw

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Utopia

Waiting for Godot

Walden

Walden Two

White Fang

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Wuthering Heights

... and coming soon, SparkNotes on

Math

Physics

Chemistry

Biology

Economics

Psychology

History

Philosophy and much more!

2

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Context 3

Context

Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. He was asymmetric in build, had one deaf ear, and stammered. He was ordained a deacon but declined to become a priest; he seldom preached because of his stutter. His religious beliefs were orthodox Anglican in every respect except that he did not believe in eternal damnation. He was an excellent amateur photographer, specializing in portraits of famous people and young girls.

He was shy and reserved around adults, but went to great lengths to meet children (especially girls) and form friendships with them. He delighted in logic puzzles and games (he even published books of some he created) and wrote thousands of inventive letters to his child-friends.

The most important of these friendships was with the three daughters of

Henry George Liddell, the dean of Christ Church. These three were favorite photographic subjects of his, and he often took them on outings and boating trips on the Thames River. His favorite of the three was the second daughter,

Alice, who was by all accounts an attractive girl. He created many extemporaneous fairy stories to entertain the three girls; the Alice books grew out of one of these stories, which Carroll wrote down at Alice’s request.

Carroll never married. He was a typical Victorian and strove for propriety in everything he did, especially in his many relationships with young girls; his personal life remains a subject of much speculation and controversy. His diary is filled with mysterious, scathing self-reproaches and desperate prayers to God to free his soul from sin. He never explains the origin of these intense feelings of guilt, but they correspond fairly closely with his periods of attachment with the Liddells. Alice’s parents abruptly broke off their daughters’ association with Carroll for a long period of time at one point, and Mrs.

Liddell burned Carroll’s early letters to Alice. The page of Carroll’s diary chronicling the break has been torn out, and only enigmatic allusions appear to it afterwards. No evidence exists that Carroll’s behavior was improper in any way towards Alice, but the fear that his feelings for her might exceed simple friendship seems to have concerned Mrs. Liddell, at least, even if

Carroll never allowed it to enter his. In any case, the Alice books, with their charmingly exaggerated presentation of the child’s quest to survive and eventually become part of the adult world, are filled with thinly-veiled references to Carroll’s affection for his young friend and deep sorrow at losing her to the onset of adulthood.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Characters 4

Characters

Alice – An English girl of about seven with an active imagination and a fondness for showing off her knowledge (which is often lacking). She is polite and kind-hearted and genuinely concerned about others. Brave and headstrong, when she gets an idea, she follows through with it to the end. She is more confident with her words and sure of her identity in the second book.

Alice in Wonderland

Cheshire-Cat – A grinning cat with the ability to appear and disappear at will. He claims to be mad; nevertheless, he is one of the most reasonable characters in Wonderland. He listens to Alice and becomes something of a friend to her.

White Rabbit – A nervous character of somewhat important rank (though not aristocratic) in Wonderland. He is generally in a hurry. He is capable and sure of himself in his job, even to the point of contradicting the King.

Queen of Hearts – A monstrous, violently domineering woman. She seems to hold the ultimate authority in Wonderland, although her continuous death sentences are never actually carried out, leading to the conclusion that she is at least partly delusional.

King of Hearts – An incompetent and ineffectual ruler almost entirely dominated by his wife. He is self-centered, stubborn and generally unlikeable.

Duchess – An odd, spiteful woman who mistreats her baby and submits to a shower of abuse from her cook. She is horribly ugly. In her anxiety to remain in the good graces of the queen she can be superficially sweet to someone she thinks can aid her socially while simultaneously inflicting the utmost discomfort.

Mad Hatter – The crazy hat-seller trapped in a perpetual tea-time. He is often impolite and seemingly fond of confusing people. He reappears in

Looking Glass as one of the Anglo-Saxon messengers.

March Hare – The Mad Hatter’s friend and companion, equally crazy and discourteous. He also reappears as an Anglo-Saxon messenger.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Summary 5

Dormouse – The Hare and the Hatter’s lethargic, much-abused companion.

Caterpillar – Hookah-smoking insect who gives Alice the means to change size at will. He is severe and somewhat unfriendly, but at least he offers assistance.

Through the Looking Glass

Red Queen – Domineering and often unpleasant, but not incapable of civility. She expects Alice to abide by her rules of proper etiquette, even when it should be apparent that she does not know what is happening.

White Queen – Sweet, but fairly stupid. She allows herself to be dominated in the presence of her red counterpart.

Red King – Asleep. Tweedledum and Tweedledee claim that he is the dreaming architect of Looking-Glass world as we know it.

White King – Bumbling and ineffectual, but not altogether unpleasant. He honors his promise to send all of his horses and all of his men with amazing swiftness when Humpty Dumpty (presumably) falls off his wall.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee – Two little fat brothers dressed as schoolboys who are fond of dancing and poetry. They are very affectionate with one another, but fight over an extremely trivial matter. They are petty and cowardly.

Humpty Dumpty – A pompous and easily-offended sort, who fancies himself a master of words. He is rude and foolish and deserves what he gets.

White Knight – Kind, gentle, and strangely noble, despite his extreme clumsiness. He tries to be very clever, but inevitably fails. He is terribly sentimental and enjoys Alice’s company immensely. He is often read as Carroll’s parody of himself.

Summary

The Alice books lend themselves almost too easily to interpretation. They are so saturated with symbols that an argument could be made for practically any

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter 1 6 position the critic wishes to take. Freudian and every other type of imagery abounds, but analyzing every jump down a rabbit hole or foot up a chimney, or every scene of eating and drinking as evidence of ”oral aggression” on

Carroll’s part, is not productive. Nothing can be known for sure about the extent of Carroll’s affections for Alice Liddell, conscious or unconscious, so even this biographical basis for analysis is highly debatable. Are the Alice books truly love-gifts of a passion doomed to remain forever ungratified, or are they simply, as Carroll maintained, the friendly indulgence of a little girl’s wish? In the end, perhaps it does not matter what is true and what is dream when talking about this collection of dreams within dreams from the mind of one Lewis Carroll, who was himself merely the dream of a kind-hearted but slightly stuffy mathematician.

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter 1

Summary

In the introductory poem, Carroll recreates the story of a boat trip on the river with three little girls on which he first created the Alice stories.

As the book opens, Alice sits on the riverbank with her sister, feeling very bored and sleepy. She sees a White Rabbit run by, wearing a waistcoat and carrying a watch and talking about how his lateness. She gets up and runs after him and follows him down a rabbit-hole. She falls down a deep well inside the rabbit-hole, the sides of which are furnished with cupboards and shelves. She falls for a long time and speculates that she may fall right through the earth. Just as she begins to doze off and dream of having a conversation with her cat, she lands on a pile of dry leaves and sticks. Unhurt, she sees the White Rabbit running off along a corridor and chases after him.

She loses it and finds herself in a long, low hall full of locked doors. She finds a little key on a glass table and finds that it fits a tiny door behind a curtain that leads to a lovely garden.

Alice cannot fit through the doorway, but she muses that perhaps she might shut herself up like a telescope if only she knew how. She goes back to the table and finds a bottle there labeled ”DRINK ME.” Finding the taste a very pleasant mixture of an odd assortment of flavors, she soon finishes off the liquid in the bottle and shrinks to a size suitable to walk through the door into the garden. She finds that she has left the key on the tabletop, however, and can no longer open the door, so she sits down and cries. She

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter 1 7 finds a glass box containing a cake with ”EAT ME” written on it in currants and eats it.

Commentary

The ”golden afternoon” of the introductory poem was July 4, 1862. The three children in the boat are the Liddell sisters, Lorina, Alice, and Edith. Alice,

Carroll’s clear favorite, is here referred to as Secunda, as she is the second oldest (Carroll is employing the Latin method of numbering girls). Also present that day was Carroll’s friend, the Reverend E. Robinson Duckworth, who later appears in the story (at the caucus-race) as a duck. Carroll was often in the habit of making up stories for the girls on their frequent rowing trips up the Thames; it was only at Alice’s insistence that he eventually turned this story into a book.

At the opening of the first chapter, Alice looks into her sister’s book and is annoyed to find that it contains no pictures or conversations. Carroll caters amply to the child’s wishes by filling his book with whimsical conversations and illustrations by the famous Punch magazine cartoonist, John Tenniel.

Carroll gradually builds the absurdity of the story with a masterful touch, first with the unremarkable event of the White Rabbit running by, then with the addition of its agitated (yet strangely human) speech, which Alice fails to recognize as unusual at first, and finally with its action of reading a watch which it takes out of its waistcoat-pocket. This device reflects the sluggish workings of Alice’s heat-addled brain, which recognizes things gradually (focusing, for example, on the waist-coat pocket and the watch instead of the larger fact that the rabbit is clothed); this technique also makes for a more acceptable transition from the real to the unreal.

Alice is quick to act, however, and impetuously throws herself down the rabbit-hole, ”never once considering how in the world she was to get out again.” In this way, the opening provides something like instructions for the reader of the book. Like Alice, the reader must suspend disbelief, accept each detail for its particular charm, and plunge headlong into the unfamiliar without lingering on ties to the everyday world. Alice shows remarkable composure and presence of mind as she falls by placing the empty marmalade jar on a shelf as she falls to avoid hitting someone below. Carroll shows for the first time here the dark edge of his humor with his parenthetical affirmation of Alice’s statement, ”’Why, I wouldn’t say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!’” The narrator agrees that this is ”very likely true,”

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 2-3 8 implying that she would not say anything because she would be dead (this is the first of many death jokes in the two books).

The narrator pokes fun at Alice’s tendency to show off her intelligence as she attempts to figure out how close she is to the center of the earth as she falls, and uses the words ”latitude” and ”longitude” without knowing what they mean because ”she thought they were nice grand words to say.” She continues to show the superficial nature of her knowledge as she speculates that she will fall right through the earth and come out among the people who walk with their heads downwards, whom she calls ”antipathies.” Now she is grateful that no one is around to hear that she does not know exactly what she is talking about. She shows herself to be very concerned with etiquette as she attempts to curtsey as she falls (Carroll addresses the reader parenthetically here to ask if he–or presumably she–could manage a thing like that), and decides that she cannot ask what country she is in when she gets there for fear of appearing ignorant.

Things immediately take on a dreamlike quality inside the rabbit hole.

Even the landscape shifts about: things like the curtain ad the ”drink me” bottle appear out of nowhere. Alice demonstrates the incompleteness of her common sense gleaned from stories about children who came to nasty ends by not remembering simple rules their friends taught them about red-hot pokers, knives, and poison. Carroll touches again on death with Alice’s musings on what would happen if she continued to shrink and went out like a candle; she then tries to imagine what a candle flame looks like after being extinguished.

Alice quickly adapts to the rules of Wonderland, and is even disappointed when she doesn’t change immediately after eating a little of the cake, as she has come to expect strangeness and regards regular things as ”dull and stupid.”

Chapters 2-3

Summary

Alice grows to over nine feet tall, and muses that she will have to send shoes as presents to her feet by mail. She goes back to the garden door and finds passing through even more hopeless than ever. She begins to cry and creates a pool of tears in the hall. The White Rabbit runs up, finely dressed and muttering about how savage the Duchess will be if he keeps her waiting, and becomes startled and runs away when Alice asks him for help. Alice picks up

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 2-3 9 the rabbit’s gloves and fan which he had dropped and begins to fan herself.

She sits and wonders what it is that has made this day so different from every other, and decides she must have been changed into someone else in the night.

She thinks of all the children her age she knows and decides she must be a poor girl named Mabel when she cannot remember her multiplication tables or geography correctly or recite a poem properly. She decides that she does not want to be Mabel and that she will stay down in the hole if anyone calls for her until she can be someone more to her liking.

Just as she begins to feel very lonely, she realizes that the fan she has been holding has been causing her to shrink and quickly drops it. She runs back to the garden door, only to find it shut again and the key out of reach on the table once more. She slips and is immersed in the pool of tears. She asks a Mouse for help, and decides it must be French when it doesn’t answer.

She uses the first sentence from her French lesson-book, ”Where is my cat?” and frightens the mouse, which protests in English that it does not like cats.

She offends it when she talks affectionately of her cat, and again when she changes the subject to a neighbor’s dog, and finally promises not to talk of dogs or cats to keep it from swimming off angrily. The Mouse promises to tell its history and Alice leads a band of birds and animals that had fallen into the pool to the shore. The animals assemble on shore, and Alice converses familiarly with them about how best to get dry.

The Mouse, which seems to have some authority, begins to recite a very dry history of William the Conqueror. The Dodo soon gets up and suggests a Caucus-race to get everyone dry. The Caucus-race is a confused affair with no clear beginning or end (until the Dodo arbitrarily announces one after everyone has stopped) and no one knows who has won until the Dodo announces that everyone has, and everyone must have prizes. They look to

Alice for these, and she hands around comfits which she finds in her pocket.

The Mouse declares that she must have a prize herself, but all she has left is a thimble, which the Dodo ceremoniously presents to her. The Mouse begins to tell its long and sad tale, which Alice’s mind shapes into the image of its physical tail. It becomes angry and storms off when it realizes that she is not really paying attention. The rest of the party breaks up hastily when

Alice begins talking about her cat, Dinah, again, and what a good mouse-and bird-catcher she is.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 2-3 10

Commentary

Alice is terribly concerned that she has lost her identity and become a poor girl with few toys, and decides to wait in the hope that she will eventually become someone else. The idea of losing her identity is less painful to her than the idea losing social status. Questions of class were very important in Victorian England, and Carroll himself was something of a snob. Alice’s frequent struggles with issues of identity, especially when tied to physical change, could also be interpreted as representative of every child’s search for self as he or she passes into adulthood. Alice’s recitation of ”How Doth the

Little Crocodile” is a parody of theologian and hymn-writer Isaac Watts’ poem, ”Against Idleness and Mischief,” which begins, ”How doth the little busy bee.” This is the first of Carroll’s many brilliant parodies of the overly educational children’s literature of the day.

The dream-like aspects of the narrative come into play again in this section as the garden door closes all by itself whenever Alice turns around.

One of the most amusing examples of Carroll’s fondness for language jokes comes in this section when Alice’s ideas of proper mouse-talking etiquette are shaped by the inclusion of the translation of the vocative case of the word for mouse (O mouse!) in her brother’s Latin grammar book. Alice speaks affectionately of her cat Dinah; the Liddells did, in fact, own a cat with that name. The history of England quoted by the Mouse is Havilland Chepmell’s

Short Course of History , which the Liddell children used in their lessons;

Carroll amusingly makes light of the lack of an antecedent for the ”it” in the passage.

The Dodo, which uses long words that it’s accused of not understanding and poses like Shakespeare, is an appearance by Carroll–he often pronounced his name Do-Do-Dodgson when he stammered. The Caucus-race, in which the participants run in confused circles and never really accomplish anything, is an obvious jab at political processes. Carroll makes extensive use of puns throughout the Alice stories, but the tale/tail pun takes on special significance in this section as the Mouse’s story is printed in the shape of its tail to reflect the train of Alice’s thoughts. This tale, with its strange element of medieval allegory in the character of Fury, is one of two scenes of unjust trials in Wonderland and ends with another reference to death.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 4-5 11

Chapters 4-5

Summary

The hall has now vanished as Alice sees the White Rabbit come along looking for its gloves and fan. The Rabbit mistakes her for its maid, Mary Ann, and sends her to fetch a pair of gloves and a fan from its house. She goes into a house with a brass plate on the door reading ”W. RABBIT” and finds the gloves and fan, along with a bottle. She drinks from it and begins to grow rapidly, and soon fills the whole house. The Rabbit comes angrily looking for

Mary Ann, and Alice knocks him down with her hand when he tries to get through the window. He calls for Pat and tells him to get the arm out of his window, and they soon collect a number of others with equipment to help.

They send the lizard Bill down the chimney, but Alice kicks him back up and out. They throw a barrowful of pebbles in through the window at her, which change into cakes as they lie on the floor. She eats one and shrinks down small enough to get through the door. She runs off past the group of animals into a wood, where she finds a puppy. She is now much smaller than it, and narrowly avoids being trampled as it tries to play with her. She runs off, determined to grow back to her proper size and find her way to the garden.

She looks about for something to eat or drink, and finds a large mushroom, with a large blue Caterpillar sitting on top smoking a hookah. The Caterpillar asks Alice who she is, and she replies that she does not know anymore. The

Caterpillar demands for her to explain herself, and she says that she cannot because she is so confused by all the changes she has been through. They have a brief conversation, in which the Caterpillar shows itself to be quite testy and demanding. When Alice complains that she keeps changing size and cannot remember things anymore, the caterpillar tells her to recite ”You are old, Father William.” She unintentionally recites a parody of the intended poem, and the caterpillar declares that it is entirely wrong. He asks her what size she would like to be, argues with her a little more, smokes silently for awhile, and then tells her that one side of the mushroom will make her taller and the other side will make her shorter as he crawls away into the grass.

She tries the mushroom, and ends up shrinking and then extending violently, until her head and neck shoot far above the treetops and is mistaken by a pigeon for a serpent in search of eggs. Alice hesitatingly remarks that she is a little girl. The pigeon doesn’t believe her and argues that little girls

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 4-5 12 must be a kind of serpent anyway if they eat eggs. Eventually, Alice manages to get herself back to her proper height and sets off to find the garden.

She comes across a little house and shrinks herself down to nine inches to approach it.

Critical Analysis

Wonderland’s dreamy quality appears again with the sudden vanishing of the hall. Alice has mixed feelings about Wonderland. She is adapting well, having figured out the relation between eating and drinking and changing size, but all the changing has become tiresome to her, and she is somewhat intimidated by the creatures and tired of being ord ered around. At the same time, she finds her situation peculiarly interesting and decides there should be a book about her.

The question of what it means to grow up arises again (Alice had told herself in the previous section that such a ”great girl” like her should not be crying–”great” meaning both mature and, literally, large). Alice’s odd habit of pretending to be two people and having conversations with herself allows her to see both sides of an issue, and perhaps helps to keep her calm and open-minded (even when she does not take the advice she gives herself).

Alice’s confusion about her identity brought on by all the changes in size she has undergone comes to the forefront once again when the caterpillar demands to know who she is, and also in her confrontation with the pigeon, when she hesitates even to say she is a little girl.

The connection between physical changes and identity again calls to mind here the child’s struggle with issues of self as it passes into adulthood. In contrast, the Caterpillar, a traditional symbol of change (as Alice herself points out), claims that physical change has no disorienting effect on him.

Alice’s growth is more an extension than a simple enlargement (i.e. she stretches out, as opposed to becoming a giant), and it confers upon her unforeseen abilities, as when she finds she can twist her neck around like a snake. The caterpillar’s seeming knowledge of what Alice is thinking is believable given that this is all a dream: the caterpillar is merely a part of

Alice’s psyche. ”You Are Old, Father William” is a parody of ”The Old

Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them” by Robert Southey.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 6-7 13

Chapters 6-7

Summary

The house belongs to the Duchess. The footman (who happens to be a frog) tells Alice not to knock and that he plans on sitting there on the doorstep for the next few days or so. The door opens and a plate flies out and grazes the footman’s nose. Alice enters through the door into a smoke-filled kitchen, and sees the Duchess nursing a baby while the Cook stirs a cauldron of soup. The air is full of pepper, causing everyone but the Cook and a large grinning cat to sneeze, and the baby howls continuously. Alice asks why the cat grins, and the Duchess explains that it is a Cheshire-Cat before screaming ”Pig!” at the baby in her arms. Alice tries to start up a conversation about how she didn’t know cats could grin, and the Duchess tells her she must not know much. The

Cook takes the cauldron off the fire and starts throwing everything within her reach at the Duchess and the baby. Alice protests, and the Duchess growls that the world would go around much faster if everyone minded his own business. Alice seizes the opportunity to show off her knowledge by explaining how that would make the night and day go by too quickly with the motion of the earth on its axis.

The Duchess hears the word ”axes” and orders Alice’s beheading. The cook pays no attention, and the Duchess begins to sing a brutal lullaby to the baby, shaking him and tossing him about the whole while. Afterwards, she leaves to get ready to play croquet and hurls the baby at Alice to nurse.

Alice has trouble holding it, and it changes into a pig in her arms and runs off. She asks the Cheshire-Cat which way she should go, and it informs her that in one direction she will find a Hatter, and in the other she will find the March Hare, both of whom are mad. It argues that everyone there is mad, including her and itself. It says she will see him later if she plays croquet with the Queen and disappears. It reappears in a moment to ask what happened to the baby, and when she tells it that he turned into a pig, he says he expected as much and vanishes again.

Alice turns toward the March Hare’s house, when the Cheshire-Cat reappears and asks if she said ”pig” or ”fig.” Alice protests that she wished he would stop appearing and vanishing so suddenly, so he disappears gradually this time, ending with the grin. Alice arrives at the March Hare’s house

(after eating a little more of the enlarging mushroom) and finds the Hare and the Hatter sitting at a large table outside having tea, with a Dormouse

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 6-7 14 asleep between them that they use as a cushion. They yell ” No room! No room!” as Alice approaches, but she sits down in one of the many empty chairs anyway.

The Hare offers her some wine, and when she protests that it isn’t civil to offer wine when there isn’t any, he replies that it wasn’t very civil of her to sit down uninvited. The Hatter tells her she needs a haircut; when she remarks that it is impolite to make personal remarks like that, he goes on to ask why a raven is like a writing-desk. Encouraged, she announces that she believes she can guess, and the Hare and the Hatter and Dormouse begin to mock her on a question of semantics. Alice can’t come up with the answer to the riddle, and the Hatter asks her what day of the month it is. When she replies the fourth (she has previously given the month as May), he looks at his watch, which tells the day of the month but not the time, and laments that it is two days wrong. He complains to the Hare that the butter was not good for its works, as some crumbs must have gotten into it when he put it in with the bread-knife. The Hare gloomily dips it into his tea.

Alice remarks how odd it is to have a watch that tells the day of the month but not the hour. The Hatter asks if her watch tells the year, to which she replies, ”Of course not,” and he retorts that his is the same way, which she does not understand. The Hatter asks if she has the answer to the riddle. She says no, and the Hatter and the Hare say they don’t know either.

She says they shouldn’t waste time by asking riddles with no answers, and the Hare replies that Time is a him and not an it. Alice doesn’t understand this either, but remarks that she has to beat time when she learns music.

The Hatter says Time doesn’t like to be beaten and explains that if she were on better terms with him, he would do whatever she liked with the clock.

The Hatter tells her that he quarreled with Time last March when he was singing ”Twinkle, twinkle, little bat” at the Queen’s concert, and now he keeps it perpetually at six o’clock, tea-time, so that they must always have the things out for tea and never have time to wash them, so they just keep moving around the table to a new set of places.

They wake the Dormouse and make him tell them a story. He tells the story of three sisters who lived at the bottom of a well, living on treacle

(molasses) and learning to draw things that start with M. Alice interrupts him periodically, and her three hosts subject her to a continual barrage of verbal abuse. Finally she becomes offended and walks off. She finds a tree with a door in it, and through the door she finds the long hall with the glass table. She takes the key, eats a bit of the reducing mushroom, and goes

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 8-10 15 through the door into the garden.

Commentary

The grinning Cheshire-Cat is Carroll’s characterization of an old expression,

”to grin like a Cheshire cat.” The phrase has no clear origin, but comes perhaps from certain Cheshire cheeses which were sold in the shape of a grinning cat. Interestingly, Cheshire is the county in England where Carroll was born. The March Hare and the Mad Hatter are also old expressions personified. ”Mad as a march hare” refers to the wild behavior of male hares during mating season, and ”mad as a hatter” refers to the tragic tendency of hat-makers to go insane from mercury poisoning, as mercury was once used to cure felt. The Duchess’s barbaric song is a parody of a poem called

”Speak Gently,” attributed to David Bates.

Carroll showed a definite preference for girls over boys, which could explain his having the only male child in the book turn into a pig. The Cheshire-

Cat, although among the few creatures in Wonderland that treats Alice with civility, has very threatening teeth and claws. The Cat provides a good transition with its pseudo-logical arguments from the Mad Tea Party, where

Carroll shows his delight in logic and mathematical puzzles that reveal some quirk or inconsistency in everyday language. For example, the Hatter’s statement that Alice can easily take more tea even though she’s had none yet sets the word ”nothing” equal to zero and makes the amount of tea Alice has consumed into a number greater than or equal to (but not less than) zero;

Alice is unaccustomed to this mathematical way of speaking. The Hare and the Hatter and even the Dormouse to an extent are rather impolite to Alice, and the Hatter relishes when he frustrates Alice enough to make her snap at him in return. Alice seems strangely unwilling to accept the nonsensical elements of the Dormouse’s story. The Hatter’s song is a parody of ”The

Star” by Jane Taylor.

Chapters 8-10

Summary

Alice finds three playing-card gardeners named Two, Five, and Seven painting white roses red. When Alice inquires, they explain that they planted the white roses by mistake and must paint them before the Queen of Hearts

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 8-10 16 finds out, or she will have them beheaded. Just then, the Queen’s procession arrives, and the three gardeners throw themselves flat on the ground. The procession is made up entirely of cards, except for the White Rabbit, who is walking along nervously with the royal guests. The Queen asks Alice her name, and then demands to know who the cards are lying face-down beside her. She replies courageously that it’s none of her business, and dismisses the Queen’s order to have her beheaded. The Queen discovers the identity of the gardeners orders them executed, but Alice hides them from the soldiers when the Queen walks on.

The Queen invites Alice to come play croquet. She learns from the White

Rabbit that the Duchess is to be executed for boxing the Queen’s ears. The game is confused and quarrelsome, with flamingoes for mallets, hedgehogs for balls, and soldiers on their hands and knees for the arches. The Queen continuously calls for beheadings. Alice is relieved when the Cheshire-Cat’s head appears to talk too, and she complains about the unfairness of the game. The Cat asks how she likes the Queen, and she catches herself and alters her answer when she realizes the Queen is right behind her. The King of Hearts comes over and decides he doesn’t like the Cheshire-Cat, and asks the Queen to have him removed (and goes off to fetch the executioner when she absent-mindedly yells ”Off with his head!”).

The King, the Executioner, and the Queen get into a dispute over whether or not the Cheshire-Cat can be beheaded if he lacks a body; they look to Alice to settle the issue. She tells them that they should ask the Duchess, since the cat is hers. They fetch the Duchess from prison, but meanwhile the Cat has disappeared, so the King and the Executioner run off to look for it while everyone else goes back to the game. Alice meets the Duchess again, who acts artificially sweet and forces herself uncomfortably close to Alice. The

Duchess agrees with everything Alice says and attaches arbitrary morals to everything. Alice politely tolerates her presence, despite her habit of digging her sharp chin in to her shoulder and her insistence that Alice stop thinking.

The Queen appears and sends the Duchess away, and everyone goes back to the game until the Queen has sentenced to death all the players except herself, the King, and Alice.

The Queen takes Alice off to see the Mock Turtle, and the King quietly pardons all the prisoners. The Queen orders the Gryphon to take Alice to see the Mock Turtle, and the Gryphon assures Alice that no one is ever really executed–it’s all the Queen’s fancy. They find the Mock Turtle sitting on a rock looking very depressed, and the Gryphon tells Alice his sorrow is not

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 8-10 17 real, but merely fanciful. Amid much sobbing and with many long pauses, the Mock Turtle tells how he was once a real turtle and went to school at the bottom of the sea. The Gryphon and the Turtle go on to reminisce about their school days and are generally rude to Alice. They excitedly teach Alice the Lobster Quadrille dance and sing her a song about a whiting, a snail, and a porpoise. They listen attentively as she recounts her adventures after seeing the White Rabbit until she gets to the part about her odd recitation of ”You are old, Father William,” when they order her to recite ”’Tis the voice of the sluggard, ”which comes out (to Alice’s dismay) as ”’Tis the voice of the lobster.” They abandon this activity, and the Mock Turtle sadly sings about beautiful turtle soup. The Gryphon rushes off with Alice when they hear someone announce the beginning of the trial.

Commentary

Alice begins to feel very bold: she decides that she has nothing to fear from a pack of cards; and brushes aside the queen’s order to have her beheaded.

This boldness dissipates somewhat under the Queen’s influence by the middle of Chapter 9. She finds comfort in the Cheshire-Cat since he acts relatively reasonably and seems above all the confusion and agitation of the croquet game. The Duchess establishes herself as an extremely sinister character in this section, acting superficially friendly while actually hurting to Alice with her sharp chin. Her obsession with morals is a parody of the preachiness of

Victorian children’s literature. Her morals are clich, hollow, and hypocritical, and many seem like veiled threats. One of them, ”Take care of the sense and the sound will take care of themselves” (a twist on the old English proverb,

”Take care of the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves”), seems to hearken back to the dispute over Alice’s statement at the tea party that meaning what she says is the same as saying what she means; in any case, the relationship between sound and sense is a recurring theme in the books.

The Mock Turtle is another of Carroll’s puns on a common phrase; mock turtle soup is actually made of veal (explaining why Tenniel’s illustration shows the Mock Turtle with the head and feet of a calf). The episode with the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle is more saturated with puns than any other in the two books as they reminisce about their schooldays together

(although the Gryphon is not generally thought of as a sea-creature–why he would be at the undersea school with the Mock Turtle is not clear). As with all explanations in Wonderland, the explanation of the lessening lessons is

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 11-12 18 cut off when it gets to a problematic spot (in this case, what happens on the twelfth day when the pattern of having lessons one hour less each day breaks down). Another death joke appears in this section with the implied ending of Alice’s recitation (which is a parody of ”The Sluggard” by Isaac Watts),

”eating the owl.” Also, the Mock Turtle singing about beautiful soup (a parody of ”Star of the Evening” by James Sayles) seems rather cannibalistic.

Chapters 11-12

Summary

They arrive at the courthouse to find the Knave of Hearts on trial for stealing a tray of tarts. The jury consists of incompetent animals and birds. The King of Hearts, who acts as judge, is also incompetent, and the White Rabbit has to remind him to call the first witness, the Mad Hatter. Alice begins to grow during the trial, to the annoyance of the Dormouse seated next to her. The

Hatter presents no real evidence, so they move on to the Duchess’s Cook, who testifies only that tarts are made mostly of pepper. The next witness called is Alice, much to her surprise.

She has grown quite large now, and she upsets the jury-box when she stands. She hurriedly replaces the jurors, and the King asks her what she knows of the tart incident. When she replies that she knows nothing, the

King tells the jury to note this piece of evidence and is contradicted by the

White Rabbit. The King writes in his notebook for a moment and then announces that Alice must leave under Rule 42 which bars anyone over a mile high from the courtroom. Alice refuses to go, and accuses the King of making up the rule just now. The White Rabbit presents an unaddressed letter from the defendant, which turns out to be a poem written in someone else’s handwriting. The King declares that the defendant must have meant some mischief by imitating someone else’s handwriting and not signing his name, but Alice contradicts him and stops the Queen from condemning the

Knave. The poem proves ambiguous, at best, but the King attempts to attach some meaning to it anyway and calls for the jury to consider their verdict. The Queen decides to give the sentence before the verdict, and

Alice, who has grown to her full size, tells her she cannot do that.

The Queen orders her beheaded, but Alice declares she isn’t afraid of a pack of cards. The cards all come flying down on her, and she awakens by the side of the river with her sister brushing some dead leaves out of her face.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 11-12 19

She tells her sister the dream she has had, and then goes in to tea. Her sister remains outside and thinks about Alice’s adventures, and while she sits with her eyes closed, the noises of the farmyard around her become the sounds of

Wonderland and all its characters. She thinks of how her sister will always keep her loving, childish heart, and will someday delight her own children with her fanciful stories.

Commentary

Carroll includes frequent parenthetical comments seemingly addressed to children, mostly encouraging them to look at the pictures. One in Chapter

11 explains the word ”suppress” in typical Wonderland fashion. Alice says she is glad that she now knows what the word means, as if she had heard the parenthetical comment herself (although her response could conceivably have been to someone in the courtroom using the word and then seeing the subsequent action). The poem used as evidence manages to remain completely ambiguous by using nothing but pronouns to denote characters (even the one detail about not being able to swim is inconclusive, as all the cards are made of cardboard and can’t enter the water); the King’s arbitrary attachment of meaning to the poem could be interpreted as a satire of literary interpretation

(if one doesn’t mind the self-incriminating implications involved).

Alice gains courage as she grows; her confidence seems tied to physical power. The mechanics of Alice’s dream become apparent in the last chapter, as fragments of her dream-world are given real counterparts. She equates the upset jurors with the previous real-life event of upsetting a bowl of goldfish, and the shower of falling cards turns out to be a flutter of dead leaves that had fallen into her face. As Alice’s sister relives her dream, the sounds of the farm yard become the sounds of Wonderland; presumably the same process took place for Alice while she was dreaming.

As the book closes, Alice’s sister imagines her growing up to entertain her children with stories drawn from the simple and loving heart of childhood.

Does this reflect Carroll’s theory that storytelling requires a certain childishness? If so, does this mean that Alice the character merges with Carroll the storyteller at the end? Or were they, perhaps, one and the same all along?

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Through the Looking Glass: Ch. . .

20

Through the Looking Glass: Chapters 1-2

Summary

In the opening poem, the speaker addresses a child (presumably Alice) and tells her to accept his fairy-tale as a remembrance of times long past.

As the book opens, Alice plays with a little black kitten in the drawingroom on a winter afternoon, and tells it to pretend to be the Red Queen from her chess set. When the kitten refuses to fold its arms properly, she threatens to put it through the mirror into Looking-Glass House, where she says everything is just like in the drawing room as far as you can see, only backwards.

The glass soon changes to a silvery mist, and Alice jumps through. She finds things quite different in the spaces that can’t be seen from the normal house, and sees the chessmen walking about on the hearth. A white pawn named

Lily begins wailing, and the White Queen yells that she must get to her child and begins to hurry over. Alice, whom they cannot see or hear, picks up the queen and places her next to the pawn, much to the queen’s surprise. She shocks the White King by lifting him up and dusting him off and then writing for him with his pencil when he tries to note the event in his memorandum book. Alice looks in a book and reads the Jabberwocky poem by holding it up to the mirror. The poems contains many strange words, and Alice does not understand most of it. She runs off to see the garden, and finds herself floating down the stairs and through the hall.

Alice finds a path in the garden that appears to lead to a hill, but every turn she takes instead leads her back to the house. She finds a bed of talking flowers, which tell her that someone else is in the garden. She turns out to be the Red Queen, now grown to life size. Alice walks toward her and finds herself back at the house again, so she tries walking away from her and soon reaches her. The Red Queen takes Alice to the top of the hill, and Alice sees that the countryside is laid out like a chess board, with squares of land divided by brooks and hedges. Alice asks to join the game, and the Red

Queen says she can take Lily’s place as the White Queen’s pawn and be a queen when she reaches the eight square. All of a sudden they start running, with the Red Queen holding Alice’s hand and yelling ”Faster! Faster!” but they stay in the same place. When they stop, the queen explains that here you must run just to keep in place, and to get anywhere else you must run at least twice as fast. The queen measures out five yards on the ground and stops as she walks along the line to give Alice instructions on how to proceed

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Through the Looking Glass: Ch. . .

21 and to say goodbye, and then she disappears when she gets to the end.

Commentary

Through the Looking Glass was written after Carroll’s relationship with Alice Liddell had waned almost entirely. The opening poem reflects his intense feelings of loss and is crowded with images of physical and temporal separation and oncoming death, themes which carry through the book like ”the shadow of a sigh.” Summer has turned to winter, and the speaker laments that his beloved child will think of him no more. Nevertheless, he finds solace for now in the shelter of his fairy-tale and invites the child to do the same.

Alice demonstrates her active imagination in the first chapter by actually talking herself into a dream. She describes to the cat her fantasy of going through the mirror and suddenly finds herself doing it, without really knowing how or when she even got up onto the mantelpiece. The looking-glass house is far from a simple mirror-image of reality; rather it’s a sort of inversion.

Much of what is not alive in the drawing-room is alive in the looking-glass house, such as the clock and the chessmen. The words in Jabberwocky must be held up to a mirror to be read, but even then, they make little sense to Alice. The language of the poem counters conventional language–sound takes precedence over sense.

Even the path outside seems alive as it thwarts Alice’s attempts to move in the conventional, forward matter; in another reversal, she must move away from something to get to it. These reversals continue throughout the book, such as when the Red Queen offers Alice a dry biscuit to quench her thirst or promises to repeat her instructions and then does not; even so, the rules of Looking-Glass World are often inconsistent or incomprehensible. For example, the Red Queen’s explanation that one has to run just to keep in place and run even faster to get anywhere (as opposed to the plain reversal of not moving to go somewhere) does not seem to hold true as Alice ambles through most of the rest of the book. Alice’s unseen manipulation of the chess pieces also seems to reverse somehow at the end of chapter 1 as she floats down the stairs and out the door, as if something is doing the same thing to her that she did to the chessmen. This already begins to point to a deterministic force in the book, a pattern of inevitably ”determined” events; for example, the Red Queen lays out Alice’s exact path for her, so that her experiences are set from the beginning.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 3-4 22

Chapters 3-4

Summary

Alice looks down on the great chessboard and sees elephants making honey like bees in one of the squares. She runs down the hill and jumps the first brook and immediately finds herself in a train filled with an odd assortment of characters who speak and even think in chorus. The train jumps over a brook, and suddenly Alice finds herself under a tree in the fourth square with a large Gnat, with whom she had been speaking on the train. The Gnat tells her about some of the odd insects in the Looking-Glass World, and he suggests several jokes for her to make. It acts extremely depressed and finally sighs itself away.

Alice comes to a wood devoid of names (she even forgets the word ”wood”).

She meets a Fawn that walks along beside her without fear while in the wood, but bounds off in fright once outside the wood (when it recognizes itself as a deer and Alice as a human). Alice continues on through another wood and runs into Tweedledum and Tweedledee, who are standing very still. They scold her for not saying hello properly, and then they all begin to dance and sing as they shake hands. Afterwards, Tweedledee recites ”The Walrus and the Carpenter.” They see the Red King asleep on the ground, and

Tweedledum and Tweedledee tell Alice that all of them (she included) are merely part of his dream. This upsets Alice, although she doesn’t believe it.

Tweedledum finds his rattle broken, and they make Alice help them dress up in makeshift armor so they can have a battle (as in an old song). They are scared off when a gigantic crow flies overhead, and Alice sees a shawl blowing along in the wind stirred up by its wings.

Commentary

Alice stops before seeing the elephant-bees without really knowing why and feels a strong desire to get to the third square as the Red Queen had instructed; she seems to be guided by an unseen, deterministic force which makes her want to abide by the rules of the game of which she is now a part. The looking-glass creatures seem to have a good knowledge of the geography of their playing field; the Gnat (who cries instead of laughing at jokes) mentions the wood where things have no names when he can’t decide on the reason for naming things. Alice speculates about the effects of losing her name, and decides it must come unstuck and attach itself to someone

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 5-6 23 else. Her concept of identity is fluid, just as in Wonderland; identities are not created or destroyed; they are merely exchanged.

The forest without names resembles Eden before Adam assigned names to all the creatures. In this version of paradise, the Fawn cannot conceive of any threat from Alice; once they exit the forest and their names are restored, however, the Fawn’s fear returns. This episode recalls the Red Queen’s last instruction to Alice to remember who she is–an unnecessary bit of advice in the regular world, but entirely relevant in the Looking-Glass World. When

Alice struggles to remember her name, she concludes that it must start with the letter L, which might remind us of the real Alice’s surname ”Liddell.”

Questions of etiquette arise when Alice meets Tweedledum and Tweedledee, who, like the Red Queen, expect her to know what to do and say.

After dancing and singing with them and feeling quite natural about it, Alice starts to anticipate their expectations for a proper guest. She becomes upset upon learning that she and everything else are all just the Red King’s dream; this dream within a dream is the central image of the book.

Chapters 5-6

Summary

Alice catches the shawl and returns it to the White Queen, who is dressed in a terribly disorderly fashion. Alice rearranges her hair and clothes and tells her she should have a lady’s-maid, and the queen offers her the job. The White

Queen tells Alice that everyone in Looking-Glass World lives backwards and their memory works both ways, and she proceeds to bandage her finger and scream before she pricks it. She also mentions that the king’s messenger is in prison for a crime he has not yet committed. Alice begins to cry at the thought of her loneliness, and the queen distracts her with a discussion of age and the belief in impossible things.

The queen’s shawl blows off again, and Alice follows her across a brook.

The queen turns into a Sheep, and Alice finds herself in a shop. The shelves all appear to be full, but then turn out to be empty whenever Alice looks straight at them. The Sheep asks if she can row and hands her a pair of knitting needles. The needles turn into oars, and Alice finds they are now in a little boat on a river. Alice picks some scented rushes, which immediately begin to fade away in the bottom of the boat.

Suddenly they are back in the shop, and Alice decides to buy an egg. The

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 5-6 24

Sheep refuses to put it into her hand and sets it up on a shelf on the far side of the shop. As Alice walks to it, the area around her becomes wooded, and she crosses a brook. The egg gets larger and turns into Humpty Dumpty as Alice approaches. She provokes him by comparing him to an egg, and

Humpty Dumpty spitefully informs her that her name doesn’t fit her shape.

Alice expresses concern for Humpty Dumpty’s safety sitting atop the high wall, but he boasts that the king has promised to send all his horses and men to pick him up if he falls. Humpty Dumpty shows off a cravat he received as an un-birthday present from the White King and Queen, and explains his method of making words mean whatever he chooses. Humpty Dumpty explains all the nonsense words in the first stanza of Jabberwocky, and then repeats a poem for Alice. The poem ends abruptly, and he dismisses her.

She walks away, and a large crash shakes the forest.

Commentary

Another twist on the reversal theme comes in this section with the White

Queen’s explanation of living backwards. This reverse mode is not simply like hitting rewind on a VCR, in which case Alice would find interacting with the creatures of this world almost impossible. In that case, the queen wouldn’t be putting the plaster on as she spoke to Alice; it would already be on, and she would take it off shortly before un-pricking her finger. Instead, actions and events seem to take place in the normal forward motion, but they take place in reverse order, so that causes come after effects, and punishments come before crimes. Also, there seems to be a possibility of the cause not taking place at all; the White Queen entertains this possibility in her discussion of the messenger’s punishment and the crime he has not yet committed. In addition, looking-glass memories work both ways, instead of just forwards, as they would in a simple reversal.

The White Queen’s claim to practice believing impossible things seems to be a comment on the suspension of disbelief required for the reader to enjoy the many impossibilities of the Alice books. The queens both emphasize structure often; an example in th is section is the White Queen’s need for a rule for being happy. She envies Alice’s freedom to be happy in the wood; perhaps the forest stands in contrast to the queens as a haven of chaos and freedom. Questions of perception play an important role in the shop as Alice finds she cannot look directly at the objects on the shelves. They also apply as Alice misinterprets the Sheep’s terms ”feather” and ”catching a crab,”

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 7-8 25 both of which are rowing expressions and have nothing to do with animals.

The dream-rushes that fade soon after Alice picks them are symbols of the transitory nature of beauty.

The episode with Humpty Dumpty emphasizes several linguistic issues.

His insistence that a name should mean something about the person while a regular word can mean whatever the speaker wants it to is another reversal of convention–normally proper nouns mean nothing in particular while common words each have a meaning. Humpty Dumpty ignores the conventional rules of linguistics here that say a word is only meaningful if it has a set meaning that the listener can interpret (although he does define the terms afterwards). He also explains the artificial etymologies of the nonsense words in Jabberwocky, many of which can now be found in the Oxford English

Dictionary.

Interestingly, Humpty Dumpty boasts that his exploits belong in a history of England; although Alice has entered an alternate dimension, she still seems to be in her own country. On the whole, Humpty Dumpty is a thoroughly unpleasant character, and he makes one of the most sinister death jokes in the books when he tells Alice she should have gotten someone to help her stop growing.

Chapters 7-8

Summary

The forest is suddenly filled with clumsy soldiers and horses. Alice finds the

White King, and soon the messenger Haigha arrives. They go off to see the

Lion and the Unicorn fighting each other for the crown (which belongs to the White King), and meet the other messenger, Hatta, who is resuming his tea after a stay in prison. They serve up white and brown bread and plumcake, and then the Lion and the Unicorn are drummed out of town (all in accordance with an old song). Alice is also scared off by the drumming and jumps a brook to get out of the town.

She is taken prisoner by the Red Knight and the White Knight in turn, who decide to fight for custody of Alice. They are both extremely clumsy, and continually fall off their horses. After a somewhat doubtful victory, the

White Knight promises to show Alice to the end of the fores, where she can cross into the eighth square and become a queen. He is terribly awkward and keeps an odd assortment of things tied onto his saddle. He tells Alice about

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 7-8 26 his inventions, which are all pathetically ineffective. Before he leaves her, he sings her a song about meeting a poor old man. She sees him off as he rides away and then enters the eighth square, where she finds a golden crown on her head.

Commentary

Haigha and Hatta are the March Hare and the Mad Hatter, respectively; their names have been rendered in Anglo-Saxon spellings for the second book. The

Hatter is still trapped in a perpetual tea-time, although his stay in prison seems to have softened him considerably. The king is fairly useless and cannot help his queen when he sees her running from an enemy, as in an actual chess game. The Unicorn sees Alice as a fabulous monster, and he and the Lion kindly offer her assistance when they see she doesn’t understand the rules of their world in serving the plum-cake.

The question of dreaming and reality arises again when Alice finds she still has the plate from what she thought might have been a dream, and wonders whether she is a dream herself. Many critics interpret the White

Knight as a representation of Carroll himself interacting with Alice. Interestingly, Chapter 8 is not named after its main character, as with Chapter

4, ”Tweedledum and Tweedledee,” or Chapter 6, ”Humpty Dumpty,” but is titled instead, ”It’s my Own Invention.” Perhaps this unexpected quotation with its first person pronoun supports the reading of the White Knight as a stand-in for the author. Certainly, the White Knight shares Carroll’s love for invention, storytelling, and logic.

Alice listens kindly to the awkward but gentle knight, who obviously cherishes her company and regrets having to let her go. The brief pause in the narration before the knight sings his song announces the importance of the episode. His song is a parody of Wordsworth’s episode with the old leech-gatherer in ”Resolution and Independence”; the tune ”I give thee all,

I can no more” indicates Carroll’s devotion to his young friend. The ”aged, aged man” of the song could be another caricature of Carroll as an unloved old man. The long series of increasingly absurd rhymes at the end of the song seems to indicate the knight’s reluctance to leave off and let go of his audience. Ultimately, his song fails to affect Alice as much as he wants. Alice sincerely wishes him well, but she is eager to get on with her own destiny–just like the real Alice Liddell.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Chapters 9-12 27

Chapters 9-12

Summary

The Red Queen and White Queen appear and give Alice an examination with nonsensical questions. After a while, the queens fall asleep with their heads in Alice’s lap. Their snoring turns to music, and Alice finds herself outside a door marked ”Queen Alice.” After Alice knocks for a while, the door swings open and Alice hears a chorus of voices singing her welcome. The singing stops when she enters, and she sees the guests are all animals, birds, and flowers. She joins the other two queens at the head of the table. The Red

Queen introduces Alice to the leg of mutton, which bows politely. She tells

Alice it is not proper etiquette to cut anyone you’ve just been introduced to and has the mutton taken away. She also introduces Alice to the plumpudding (despite Alice’s protests) and orders that taken away. Alice orders it brought back and serves a slice to the Red Queen. The pudding scolds her for her impropriety. The White Queen recites a riddle in verse about a fish with a sticky dish- cover. The company toasts Alice’s health, and then the room explodes in confusion.

Alice picks up the Red Queen (who has shrunken considerably), and shakes her. The queen gradually turns into the black kitten, and Alice finds herself back in her drawing room. Alice tries to make the black kitten confess to having turned into the Red Queen, with no success. She looks down at the white kitten, which is being cleaned by Dinah, and decides she must have been the White Queen (and that the cleaning explains why she was so disheveled in the dream). She thinks perhaps Dinah became Humpty

Dumpty but is not sure. Then she asks the black kitten to settle the question of whether it was her dream or the Red King’s, but the kitten only goes on licking its paws.

Commentary

The examination is another example of how the queens expect Alice to think like they do (or better, in the White Queen’s case) and follow their rules.

The Red Queen’s statement that even a joke should have meaning seems to apply well to all of Carroll’s meaningful nonsense. The banquet has some disturbing cannibalistic overtones with the talking food and the White Queen in the soup. Alice gains confidence at the banquet and stands up to the Red

Queen by ordering to have the pudding brought back. She eventually comes

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Questions for Study 28 confronts the Red Queen, picking her up and shaking her into a kitten. In the chess problem that structures the book, this represents Alice’s capture of the Red Queen, which results in the checkmate of the dreaming Red King, immediately ending the dream. Alice apparently begins to wake up gradually even before this, as the Red Queen begins acting like a kitten (chasing her tail); she even predicts that the queen will turn into a kitten while shaking her. Just as with the dream in Wonderland , tangible counterparts exist for elements of the dream-world. The question of the dream within a dream and the identity of the true dreamer remain unresolved in the end.

With the closing poem, Carroll goes back yet again to that boat trip on the Thames. The poem is an acrostic–the first letters of each line spell out Alice’s full name, Alice Pleasance Liddell. This poem is again filled with images of winter and death and unfulfilled longing. The speaker declares that

Alice haunts him yet in the terrain of dreams–perhaps not only Wonderland, but his own personal dreams as well.

The poem ends with a rhetorical question that says all life is but a dream.

Questions for Study

Where did Carroll find the inspiration for his Alice character?

Alice is largely based on Alice Liddell, the second daughter of the dean of the university where Carroll (or Dodgson) taught mathematics, who was present when he first told the Alice stories.

How do the characters react to Alice as an outsider in each of the two books?

In Wonderland, most of the characters seem either indifferent or slightly annoyed at Alice’s presence. They do not recognize her as a stranger to their world and interact with her in essentially the same way they treat each other– they expect her to understand what is happening. In the Looking-Glass

World, they sometimes expect her to know exactly what to do and say (as with the Red Queen or Tweedledum and Tweedledee); however, sometimes

(as with the Unicorn and the Lion) they recognize that she is from a world quite unlike their own and explain to her how to act.

What role do issues of social class play in the books?

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Questions for Study 29

In both Wonderland and the Looking-Glass, strict social hierarchies exist.

These same hierarchies exist in Alice’s Victorian England, and she is conscious of her high social status and fears losing it (as in chapter 2 of Wonderland when Alice thinks she has turned into Mabel). Alice is excited in

Looking Glass to meet a real queen, and her journey as a pawn to become a queen could be interpreted as one of social advancement (although at least one of the pawns is the daughter of the White Queen, and thus the position of a pawn may be enviable to begin with in the Looking-Glass World).

The royal characters in the Alice books are some of the most unsympathetic, childish and selfish, and even Alice becomes slightly tainted when she becomes a queen (she is described as anxious to find fault with everyone, she refuses to ring the bell for visitors or servants, and is concerned about having the ”right people” invited to her dinner party).

Discuss the differences between the structures of the two books and the thematic implications involved.

The dominant image of Wonderland is the pack of cards. The story seems to proceed in a more or less random fashion, reflecting the prominent role of chance in a game of cards.

Looking Glass is structured around a chess game.

As chess is a game of skill, this seems to imply some controlling influence behind the events of the second book. So thematically, the first book focuses more on the bewildering arbitrariness of the adult world, while the second book emphasizes a sense of destiny and predetermination (consequently creating a somewhat darker tone).

Discuss the differences between the two books with regard to Alice’s thematic role.

In the first book, Alice represents childhood (despite her personal peculiarities and fairly definite social position) and the child’s struggle to survive the confusing world of selfish adults. Ultimately, Alice masters the adult method of interaction and enters into the grown up world on equal terms with its other inhabitants. In the second book, Alice again confronts a confusing set of rules and must learn to deal with them, but this time the advancement seems more social in nature than the biological process of growing up (for one thing, Alice undergoes no physical changes in this book). Alice advances along a set path and undergoes an initiation ritual to reach a high social position; the rules of behavior she is expected to master are those of a particular group within the social order.

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Questions for Study 30

Provide evidence for determinism in Through the Looking Glass .

The central image of the chess game implies some unseen force behind the events of the story, especially after the scene in the first chapter in which

Alice moves the chess pieces about without them being able to see or hear her. Also, the events are laid out for Alice by the Red Queen before she even starts on her journey across the board, and she feels strangely compelled to follow the set path, despite her curiosity about things that lie beyond (such as the honey-making elephants). In addition, most of the characters she meets along the way are taken from songs or poems (which are always quoted) and follow the plots of their respective sources.

Discuss the implications throughout much of Wonderland of Alice’s aim to reach the garden she sees through the little door.

Alice glimpses the garden through the little door and adores its loveliness; getting there becomes the only real goal she sets for herself in the book. When she finally arrives in the garden, however, she finds its loveliness tainted by the overbearing presence of the queen and the courtiers and the unpleasantness of the croquet game. This could be interpreted as a comment on false or faded ambitions, or perhaps the illusory joys of the child’s perspective of adulthood, which is inevitably disillusioning.

Discuss Carroll’s manipulation of the visual structure of the text (paragraph shape, type size, etc.).

Carroll plays with the visual presentation of characters’ dialogue to reflect some quality of the character’s voice or Alice’s reception of it. He often uses a smaller type size to indicate a small voice (as with the Gnat in Chapter 3 of Looking Glass ) or all CAPS to indicate yelling (as with the Tweedledum’s angry yelling in Chapter 4 of Looking Glass ). The most striking example of the text’s visual presentation comes in Chapter 3 of Wonderland , when the

Mouse’s tale is presented in the shape of its tail to reflect Alice’s thoughts as she listens to the story.

Discuss the relationship between the red and white chess characters in Through the Looking Glass .

The two armies in the chess game compete with each other (the White Queen is seen running from an enemy in Chapter 7, for instance), but harbor no

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.

Questions for Study 31 deep enmity toward one another. The whole affair runs like a contest, rather than a conflict. The two queens seem quite comfortable with each other, and even the White Knight and Red Knight part on friendly terms after their battle.

Discuss how the game-piece characters reflect the properties of their real-life counterparts.

In Wonderland , the card characters are unidentifiable from the back, made of cardboard, and organized into a social hierarchy or caste system according to their suit (spades are gardeners, clubs are soldiers, and so on). The most significant game parallels come in Looking Glass : the chess piece characters move according to the rules of the game. Queens can move swiftly and freely, kings move (and do) very little, and Alice, as a pawn, moves steadily straight ahead after her initial two-square move (via railway).

Copyright 1999-2000. iTurf Inc.