Leadership in Uganda, Barbados, Canada and the USA

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/2040-0705.htm

Leadership in Uganda, Barbados,

Canada and the USA: exploratory perspectives

Terri R. Lituchy

John Molson School of Business, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada

David Ford

School of Management, University of Texas at Dallas,

Richardson, Texas, USA, and

Betty Jane Punnett

Department of Management Studies, University of the West Indies,

Cave Hill, Barbados

Leadership

201

Received 16 May 2012

Revised 17 August 2012

12 November 2012

Accepted 16 November 2012

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to consider effective leadership in Africa and the African diaspora. This paper reports the results of emic research in Uganda, Barbados, Canada and the USA.

Design/methodology/approach – A Delphi technique using open-ended questions solicited ideas regarding leadership from knowledgeable participants, avoiding researcher bias.

Findings – There were differences among the groups on several attributes that made leaders effective.

Ugandans suggested a good leader was “honest and trustworthy”; Canadians and respondents from the

USA said “being inspirational/charismatic” Barbadians cited “being a visionary”.

Research limitations/implications – Having data for only one African country and the small sample sizes from all countries limit the generalizability of the findings. The results do, however, provide a base of knowledge on which to build future studies on Africa and the diaspora.

Originality/value – The emic approach overcomes the western bias identified by scholars in most

African research. Similarities and differences identified provide evidence of the importance of culture in effective leadership. The results provide a basis for developing further research studies.

Keywords Uganda, Africa, Leadership, National cultures, Management studies, Research work,

Effective leadership, Diaspora, International human resource management

Paper type Research paper

1. Introduction

Management scholars have pointed to the fact that management knowledge is severely biased towards “Western” perspectives (Baruch, 2001; Bruton, 2010; Thomas, 1996;

Thomas et al.

, 1994; Werner, 2002). This is not surprising, given that the overwhelming proportion of active management researchers are from North America and Western

Europe, where a tradition of rigorous academic research in management has developed over the past 50 years (Thomas, 1996; Punnett, 2008). Management issues such as leadership and motivation have been studied only to a very limited degree in developing countries, and both Africa and the Caribbean are noticeably absent from most research.

In contrast, developing countries are making their presence felt in the current international business environment and are becoming increasingly important players in the world economy; The Economist (2010, p. 3) says:

African Journal of Economic and

Management Studies

Vol. 4 No. 2, 2013 pp. 201-222 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited

2040-0705

DOI 10.1108/AJEMS-May-2012-0030

AJEMS

4,2

202

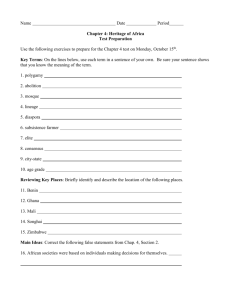

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for study

Emerging-market banks have raced ahead despite the financial crisis [ . . .

] not only are they well capitalised and well funded, they are really big – and enjoying rapid growth [ . . .

] they now account for a quarter to half of global banking industry.

From a management perspective, there has not been a similar shift in knowledge, and we know little about effective management in developing countries. Das et al.

(2009) found that research papers published in mainstream economic journals are linked to level of development. They found that countries with the lowest incomes and weakest economies receive the least attention in the literature; for example, over a 20-year period they identified only four papers on Burundi and more than 37,000 on the USA.

This unbalanced view of management and leadership needs to be addressed. This study, which is part of a larger research program, was designed with this concern in mind. Specifically, the objective is to examine and measure leadership in Africa and the African diaspora who reside in countries outside of Africa. Hence, the research program known as “leadership effectiveness in Africa and the diaspora” (LEAD).

1.1 Research questions

The overall objective of this study is to look at leadership in four countries which represent Africa and its diaspora – Uganda, Barbados, Canada and the USA. Although only one African country is included in this exploratory study, subsequent phases of the research will include other African countries throughout the African continent as the project progresses.

We address the following research questions in this paper:

RQ1.

What are the similarities and differences in descriptions of culture among the four countries?

RQ2.

What are the similarities and differences in leadership among the four countries investigated?

The LEAD research program is in its early stages of execution, and this report provides results for the initial phase of the project. That is why the scope of countries and regions reported on here is rather limited. The theoretical base that guides our LEAD research program is an integration of implicit leadership theory (ILT) (Lord and Maher, 1991) and value-belief theory of culture (Hofstede, 1980). Though not as extensive and ambitious as the global leadership and organizational behavior effectiveness (GLOBE) project

(House et al.

, 2004), the LEAD research program has comparable aims and draws on a similar theoretical base as the GLOBE project (House et al.

, 2002). For the present study, the conceptual framework shown in Figure 1 “loosely” guides our inquiry and provides

P2

Culturally Endorsed

Implicit Leadership

Theories (CLTs)

P3

Societal Culture

Norms & Practices

P1 Leader Attributes

& Behaviors

Leader

Effectiveness

the basis for the theoretical underpinnings of the research. The primary premise of the conceptual framework is that the attributes and entities that differentiate one culture from another culture are predictive of the leader attributes and behaviors that are most frequently enacted and are considered effective in that culture.

The methodology of the study is such that we avoid imposing Western-based views on the project. We use an emic approach, which develops the definitions and descriptions of the variables being considered, based on the responses from the participants in the research. Methodologically, we do not use standardized definitions, based on Western-originated literature. The research begins with a “blank page” and asks participants to develop the information themselves. Research of this kind is unusual and provides richer data than that provided by structured, quantitative, hypothesis-driven research, and it does not lend itself to the “traditional” statistical analysis that is typical of quantitative research studies. We believe that this emic approach is most appropriate for a study such as the present one, where we want to avoid the Western-based biases of previous research. The results of this research provide insights into what our participants think about effective leadership from their own perspectives and in their own contexts.

1.2 Implicit leadership theory

According to this theory, leadership perceptions are seen to form a number of hierarchically organized cognitive categories, each of which is represented by a prototype. The prototypes are formed through exposure to interpersonal interactions and social events. Therefore, individuals have implicit beliefs, convictions, and assumptions concerning attributes and behaviors that distinguish leaders from followers, effective leaders from ineffective leaders, and moral leaders from evil leaders. These beliefs, convictions, and assumptions are referred to as individual ILTs.

That is, an observer’s prior knowledge and understanding about human behavior and underlying traits comprise her or his ILT, which is used to make a connection between the observed leader’s characteristics and the prototypes of a leader in the observer’s mind (Lord et al.

, 1984). For example, high intelligence, charisma, and decisiveness are often thought to be key attributes or characteristics of effective leaders in the USA.

These attributes are often associated with the prototype, “effective leader.” The ILTs held by individuals thus influence the way they view the importance of leadership, the values they attribute to leadership, and the values they place on selected leader behaviors and attributes (House et al.

, 2004).

1.3 Value – belief theory

According to value-belief theory (Hofstede, 2001), the values and beliefs held by members of cultures influence the degree to which the behaviors of individuals, groups and institutions within cultures are enacted, and the degree to which they are viewed as legitimate, acceptable, and effective. Hofstede’s version of value/belief theory includes four dimensions of cultural values and beliefs: individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, tolerance versus intolerance of uncertainty, and power distance (stratification) versus power equalization. The GLOBE research project substituted two cultural dimensions, labeled gender egalitarianism and assertiveness, for Hofstede’s masculinity-femininity dimension and also added three additional dimensions: humane orientation, performance orientation, and future orientation,

Leadership

203

AJEMS

4,2

204 which are conceptually analogous to the affiliative, power, and achievement motives in

McClelland’s (1985) implicit motivation theory. Collectively, the GLOBE researchers believed that the nine core GLOBE cultural dimensions reflect important aspects of the human condition. Comparable dimensions were created by the GLOBE researchers to represent dimensions of organizational culture. For leaders in the GLOBE countries, the goal was to identify “universal” as well as culture-specific dimensions of culture that contributed to a leader being effective.

The following sections review the literature on leadership from an African perspective and highlight several ILTs that are operative in Uganda, Barbados, Canada, and the USA. We then offer three propositions based on our review that illustrate the relationships shown in Figure 1.

2. Leadership research in context

Consensus over one definition of leadership has not emerged among leadership scholars (Grint, 2005; Yukl, 2005). It is however possible to trace common themes in many of the leadership definitions that have been proposed over the years. The most common definitions see leadership as a social influence process to achieve a common goal (Shamir et al.

, 1993), the voluntary acceptance of this influence ( Jago, 1982; Kotter,

1988), and change in the motivational state of the followers. One definition that incorporates several common themes is:

Leadership is the process of diagnosing where the work group is now and where it needs to be in the future, and formulating a strategy for getting there. Leadership also involves implementing change through developing a base of influence with followers, motivating them to commit to and work hard in pursuit of change goals, and working with them to overcome obstacles to change (Paglis and Green, 2002, p. 217).

This definition illustrates what is seen in the west as important in effective leadership, that is, a future orientation, a strategic approach, valuing change, influencing, commitment and hard work towards goals. We do not know that these same characteristics will be seen as important elsewhere. Rather than imposing such a definition, we want to develop a definition from the perspective of our respondents and to see how that perspective is similar to, or different from, the previous definition.

Comparative research has sought generally to identify similarities and differences in perceptions of leaders, the characteristics of leaders, and the fit between country/culture and leadership behaviors. The GLOBE project (House et al.

, 2004), involving 62 societies around the world, asked, “How is culture related to societal, organizational, and leadership effectiveness?” (p. xv). The study found both cross-country similarities and differences. For example, “charismatic” leadership is universally seen as most desirable, and “self protective” leadership is universally seen as undesirable; other styles however are culturally contingent. While their research in Africa and the Caribbean is limited, based on the GLOBE findings, we expect to find both similarities and differences across the countries in our study.

2.1 Leadership – an African perspective

The last two decades have seen increased interest in organizational and human resource challenges on the African continent (Wambu and Githongo, 2007). Scholars have addressed topics such as the suitability of Western-based management, as well as

HR practices (Blunt and Jones, 1992; Horwitz et al.

, 2002; Kamoche et al.

, 2004), the role

and impact of culture (Jackson, 2004), and the emergence of indigenous ideas like Ubuntu and Indaba (Mangaliso, 2001; Mbigi, 2000; Newenham-Kahindi, 2009). Yet, Africa remains relatively under-researched (Lituchy et al.

, 2009).

The approach of many management studies in Africa has been to test Western-based management theories in Africa (Blunt and Jones, 1997; Wheatley, 2001; James, 2008) often using previously established scales. This approach does not incorporate local issues or consider the specific cultural elements that may be important in the new context. Essentially, researchers see their own reflections in such studies. The good news is that researchers are realizing the disadvantages of this approach and have highlighted the need for a local aspect to African studies (Beugre and Offodile, 2001; Bewaji, 2003;

Obiakor, 2005). This “contextualization” of the issues under investigation has been adopted by other scholars recently, especially with respect to research on China (Tsui,

2004, 2006).

In a study that focused on the leadership development process in three African countries, James (2008) noted that effective leadership development requires understanding and application of local contextual and cultural issues. He pointed toward severe poverty, economic and social problems, low credibility of leadership, resource constraints, high risk aversion and very high proportion of male leaders as the contextual issues and cultural elements specific to African countries. He believes that without taking these factors into consideration, the efforts to improve leadership in

Africa will not materialize. In his words, “most leadership development programs use imported Western models that at best pay only lip-service to the very different culture and context in Africa.” McFarlin et al.

(1999) also shared similar concerns that the challenges of management development in Africa cannot be met successfully without embracing the “Leadership and training approaches that better reflect African values”

(p. 63). Bolden and Kirk (2009) suggested that in order to have sustainable leadership development in Africa, African managers, leaders, organizations and communities need to develop or enhance their own approaches. This requires help to liberate themselves from colonial and post-colonial thinking. An Afro-centric style of leadership requires a reconnection with African indigenous knowledge. These authors criticized the Western-based approach in African studies which focused on having business advantages and ignored African needs.

Obiakor (2005) also criticized the propagation of Western leadership theories in

African educational institutions. He suggested that the theories of Western-based leadership should be replaced with theories of African leadership, and these should be taught to the African children from very early age. However, this shift, as noted by

Bolden and Kirk (2009), is not easy.

Those authors that address indigenous issues in an African context highlight the differences in findings, compared to Western-based theories. Blunt and Jones (1997) suggested that in Africa, the effective leadership styles are more paternalistic than the effective leadership styles in the west and that in Africa, interpersonal relations are placed higher than individual achievement. Mathauer and Imhoff (2006) had similar findings. They found that non-financial motivational tools and a more paternalistic leadership style, reflecting “caring” on the part of management, were more effective in African countries.

Hale (2004) thought that the transformational leadership model was not the most effective leadership model in the African perspective. He found West Africa high

Leadership

205

AJEMS

4,2

206 on hierarchy, with leaders expected to be powerful and to make decisions. He proposed an effective leadership model for Africa as a blending of transformational leadership theory with servant leadership, the components of which include egalitarianism, moral integrity, empowering, empathy, and humility (Mittal and Dorfman, 2012; Spears,

1998). Along somewhat different lines, Walumbwa et al.

(2005) compared the relationship of transformational leadership to organizational commitment and job satisfaction in the USA and Kenya. They identified African leadership as authoritarian due to high power distance and hypothesized that this may negate the positive impact of transformational leadership. They found that respondents from the USA rated transformational leadership and satisfaction higher than Kenyan respondents; however, they found that in both cultures the relationship between transformational leadership and commitment and satisfaction was positive.

In contrast to the studies that indicated the importance of the dimensions of hierarchy and power in Africa, Smith (2003) looked at leadership roles and identified spirituality, time as eternal, importance of ancestors and connection of ancestors and land, strong relationships and communalism as important; he concluded that culture has a significant impact on cultural styles and that, in Africa, leaders are expected to be tough, but decisions are holistic and collective. McFarlin et al.

(1999), Mangaliso (2001) and Newenham-Kahindi (2009) stressed indigenous leadership styles such as Ubuntu and Indaba – endorsing factors such as supportiveness, relationships, extended networks, as well as spiritualism and tribal destiny. They suggested that trust is based on interpersonal relationships, open discussions involving participation from all employees, and discipline based on how the individual affects the group. Mbigi and

Maree (1995) also focused on the concept of Ubuntu, described as a sense of brotherhood among marginalized groups combined with spiritualism.

In a recent report on leadership in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA), Wanasika et al.

(2011) provide the very first glimpse of data on Africa from the massive GLOBE project. The countries of Namibia, Zambia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and South Africa were represented.

The object of the study was to determine which dimensions of culturally endorsed implicit leadership theories (CLTs) were seen as contributing to outstanding leadership, as well as determine which societal culture dimensions were evidenced in the countries. The SSA countries strongly endorsed the GLOBE leadership dimension of charismatic/value-based leadership, which is often exhibited by African leaders through the art and skill of oratory (Wanasika et al.

, 2011).

Additionally, team-oriented leadership was strongly endorsed by the SSA countries, and the authors noted that this dimension reflects traditional elements of tribal leadership. Human-oriented leadership, which has distinct similarities to Ubuntu, received a strong endorsement by the SSA countries as well. Former South African

President Nelson Mandela was cited as an example of a leader whose actions reflected the African cultural value of Ubuntu through respect and inclusion of all stakeholders in negotiations and decision making (Wanasika et al.

, 2011).

Overall, there seem to be two streams of findings in this African research. One is the powerful leader, who uses his place at the top of the hierarchy to accomplish his objectives, and the other is the communal, servant leader, who sees his role as leading for the good of others (note that the pronoun he is used intentionally here, because of the predominance of males in leadership positions in Africa).

Furthermore, these studies suggest that effective leadership in African organizations may be different from that found in a Western context. The studies also suggest that some behavior considered ineffective in Western countries could, in fact, be effective and desired in the African context.

The African societal cultural values identified in the above-cited studies include hierarchy and power distance, importance of ancestors, strong relationships, communalism, and Ubuntu, with a focus on supportiveness, spiritualism, tribal destiny, and external networks (Mangaliso, 2001; Mbigi and Maree, 1995). These societal values bear a strong resemblance to the GLOBE project’s (House et al.

, 2004) cultural dimensions of assertiveness, institutional collectivism, and humane orientation.

2.2 Leadership – the African diaspora

For this study, we define the diaspora broadly as anyone with roots going back to

Africa. A large number of people of African descent live in several different parts of the world. The number of African diaspora is approximated to be around 140 million

(The World Bank, 2010). Despite this large number, the role of African diaspora has generally been overlooked in the business and management literature. There are few scholars that have studied the importance of African diaspora, in human resources or cross-cultural management for example, especially in developed countries such as the USA and Canada. Gramby-Sobukwe (2005) highlighted the important role that the

African diaspora are playing through organizations such as churches, grassroots organizations, and the press for the improvement of leadership in the African countries.

The author suggested that the African diaspora in the USA play an important and positive role for the betterment of African countries through helping the democratic leaders in Africa. That is, African Americans most effectively contribute to democratic development in Africa when they encourage effective and responsive leadership by interacting at the level of culture and civic organizations (Gramby-Sobukwe, 2005).

Mohan and Zack-Williams (2002) also suggest that the diaspora has to play an important role in the social processes, both politically and economically. Thus, the African diaspora are important actors, which should not be ignored in any study focusing on the development of leadership practices in Africa.

In the Caribbean, a large percentage of the population has its roots in Africa, based on the slave trade, and only a small number are new immigrants from Africa. In many

Caribbean countries the people of African origin make up over 90 percent of the population. In the USA many African Americans also have their roots in Africa because of the slave trade. African Americans, in contrast to the Caribbean, do not constitute the majority of the population, and there are a larger percentage of new immigrants who come to the USA from Africa. In Canada, African Canadians are more likely to be new immigrants who have chosen to go to Canada for economic and social reasons. African Canadians associated with the slave trade, are largely descended from those who escaped from the USA and found their way through the underground railway to Canada. Because of these differences in background, motivation, and environment, we expect to find both similarities and differences among participants from Barbados,

Canada, and the USA. There are few studies that consider the African diaspora, from a management perspective. For the purposes of this study, we are focusing on the diaspora in North America and the Caribbean; however, it would clearly be desirable to extend this to other regions, including Europe and Latin America.

Leadership

207

AJEMS

4,2

208

The Caribbean presents an interesting case of African diaspora, who have lived in the region for generations and the culture is a blend of African influences and the colonial practices. People of Sub Saharan descent represent around 73 percent of the total Caribbean population (CIA, 2010). Though the research on African countries is scarce, management research in the Caribbean is even more limited. Punnett et al.

(2006) have carried out a number of recent studies but these are only a beginning.

Punnett and Nurse (2002) reviewed the literature on management in the Caribbean and concluded that there was very little in the field. They pointed to literature on economics and social issues but virtually none on management, leaving the field open for development. Punnett et al.

(2006) examined some cultural factors in the Caribbean as they relate to management issues and concluded that cultural factors were an important consideration in effective management practices. Punnett and Greenidge

(2009) reported on cultural measures from the Caribbean that indicated a mismatch between cultural values and management, and suggested a need to explore issues of leadership and motivation in more depth. A small number of other studies in the

Caribbean have explored specific aspects of management such as absenteeism

(Punnett et al.

, 2007), occupational mental health (Baba et al.

, 1999; Baba et al.

, 2010), participation (Nurse and Devonish, 2008), goal setting and performance (Punnett et al.

,

2007) and leadership in cricket teams (Corbin, 2009), but these are essentially isolated studies which do not lead significantly to a more general understanding of leadership effectiveness. Rather, they point to the range of organizational issues on which effective leadership can have an impact. Further, we are not aware of any research in the management field that attempts to examine issues across African countries and among members of the African diaspora in countries outside of Africa.

The USA has the largest number of African diaspora living in any single country of the world. They are around 38 million, accounting for about 12 percent of the total US population (CIA, 2010). Canada, on the other hand, has a relatively small population of

African diaspora with around 800,000 people accounting for around 2.7 percent of the population (Statistics Canada). Thus, Canada provides a contrast to the Caribbean and the USA, where the population of African diaspora is high.

In terms of culture, the Caribbean people appear to be low on hierarchy/power distance, moderate on individualism, and high on uncertainty avoidance – preferring certainty and avoiding risk (Punnett et al.

, 2006; Punnett and Greenidge, 2009); Canada and the USA are generally seen as individualistic and relatively low on both power distance and uncertainty avoidance presenting a contrast to the Caribbean. People in the Caribbean are also found to be high on cooperation, accommodation and social cohesion, and their leadership style has been classified as transformational (Cole and

Berengut, 2009).

The Canadian and American management literature is abundant; however, there is little research focusing on the Africa diaspora, or comparing the diaspora with African countries. In the USA some studies have focused specifically on African Americans, but these studies have not compared African Americans with the African diaspora elsewhere, or with people from Africa.

The societal cultural norms and values identified in the diaspora studies include high uncertainty avoidance, high cooperation and social cohesion, moderate individualism, low hierarchy and low power distance. These societal values bear a resemblance to the

GLOBE (House et al.

, 2004) cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance, human orientation, power distance, and possibly in-group collectivism.

Further, dominant cultural norms that are endorsed by societal cultures give rise to leader behavior patterns (and organizational practices) that are differentially expected and considered legitimate among cultures (House et al.

, 1997; Schein, 1992). Therefore, the attributes and behaviors of leaders are, in part and indirectly, a reflection of societal cultures (Kopelman et al.

, 1990).

Based on the literature reviewed, we offer the following propositions as initial guides for our study:

P1.

Societal cultural values and practices affect leader attributes and behaviors.

P2.

Societal cultural values and practices affect the process by which people come to share ILTs.

P3.

Leader effectiveness is a function of the interaction between CLTs and leader attributes and behaviors.

We conclude, on the basis of our literature review, that:

.

.

.

.

There is little research on leadership in Africa or the African diaspora; more work is required in almost every field to better understand the concept of leadership within the African diaspora and Africa.

Much of the management research on Africa is biased towards Western-based theories and concepts; only a few researchers have tried to understand the concept of leadership from the perspective of African people.

Studies that have focused on the cultural uniqueness of African countries suggest that effective leadership styles and motivational tools in Africa are different from Western countries; for example, a paternalistic leadership style, tribal ties, non-financial rewards, spirituality, communalism, supportiveness and local concepts such as Ubnutu, all play important roles in Africa but are not as important for leaders in Western countries such as the

USA and Canada.

There is no management research on the African diaspora in Canada, the

Caribbean or the USA in comparison to persons in Africa. Therefore, the present exploratory study was undertaken.

3. Method

3.1 Delphi process

In order to avoid the “Western” bias described as a flaw in many management studies

(Baruch, 2001; Thomas, 1996; Thomas et al.

, 1994; Werner, 2002), an emic approach was used. Emic research focuses on the intrinsic distinctions that are meaningful for a given group. The research began with a “blank page”, by asking respondents to define the concepts to be measured, rather than defining them ourselves. This was done through a Delphi process, which asks participants to define then refine the details of the variables to be investigated.

The Delphi technique has been described as a method for structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem (Linstone and Turoff, 1975). The process is

Leadership

209

AJEMS

4,2

210 used to establish as objectively as possible a consensus on a complex problem, in circumstances where accurate information does not exist or is impossible to obtain economically. Usually, a Delphi consists of a series of rounds in which information is collected from panellists, analyzed and fed back to them as the basis for subsequent rounds; giving an opportunity for individuals to revise their judgments on the basis of this feedback (Linstone and Turoff, 1975).

The Delphi process traditionally begins with an open-ended questionnaire (Hsu and

Sandford, 2007). The open-ended questionnaire serves as the cornerstone of soliciting specific information about a content area from the Delphi subjects (Custer et al.

, 1999).

After receiving subjects’ responses, investigators convert the collected information into a more structured format and each participant receives a summarized copy of their individual responses from the first round. Rounds continue until essential consensus is reached among the subjects.

The Delphi research questionnaire was developed through a relatively lengthy process. First the main researchers drafted an outline; this was discussed and refined at a workshop, which included participants from an African country (Nigeria), the

Caribbean (Barbados and St. Vincent and the Grenadines), Canada, and the USA

(an African American). The refined version was circulated for additional comments before a draft for use in Kenya was completed. In Kenya, two of the researchers from the workshop met with the Kenyan researcher, and revised the questionnaire. One major outcome of this refinement was the addition of “in your community” to many of the questions as the Kenyan researcher felt this would make the questions more meaningful in this context. The Kenyan researcher believed that many Kenyan respondents would think of their tribe when responding to this question; however, the other researchers felt that the use of “tribe” would mislead respondents, so the word

“community” was selected, as this allowed for respondents to raise the issue of tribe if this was important to them, but allowed for other interpretations as well.

3.2 Participants

Knowledgeable people were identified from the following groups:

.

.

academics; private sector;

.

.

public sector; and other – religious leaders, leaders in non-governmental and charitable organizations, community leaders.

A minimum of seven experts was surveyed in each country. In countries with larger

African populations more knowledge people were included. For the present study, there were 11 participants from Uganda, 15 from the USA, seven from Canada, and eight from Barbados.

All individuals had leadership experience at their place of work and/or in their respective communities. In Uganda, two participants were female and nine were male; their ages ranged from 25 to 70 years with an average of 40.4 years. The highest level of educational attainment ranged from high school to post-graduate level. In Barbados, five participants were female and three were males. Their ages ranged from 26 to 51 years, with an average of 38.5 years. The highest level of education ranged from bachelor’s

degree to doctoral level. In Canada, two participants were female and five were males; ages ranged from 49 to 77 years with an average age of 60.8 years. Education levels included one who was self-taught, six with at least some university-level education, and three who had PhDs. In the USA, eight participants were female and seven were male; ages ranged from 44 to 70 years with an average age of 56. Education levels ranged from high school to university level education (three of the nine university educated persons held PhDs).

3.3 Procedure and analysis

We began by identifying people who fit the definition of knowledgeable people.

We asked if they would participate in the project. If they agreed, questionnaires were sent to them in Barbados and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Uganda, Canada and the

USA. In all cases, the purpose of research was explained and confidentiality of individual responses was assured. The Delphi questionnaire included seven open-ended questions:

(1) What words/terms come to mind when you are asked about your culture?

(2) What aspects of your culture (based on question 1) contribute to being an effective leader in your community?

(3) What words/terms would you use to describe an effective leader in your community?

(4) What words/terms would you use to describe what effective leaders do?

(5) What words/terms would you use to describe what motivates leaders to succeed?

(6) Name three to five people, men or women, whom you consider to be, or to have been, effective leaders (they can be local, national or international), and several words/terms that explain why do you feel each person is effective?

(7) Give three to five words that describe your ethnic or cultural background.

This report is based primarily on data taken from questions 3, 4, and 6 of the Delphi questionnaire. Data from questions 1 and 2 were combined to provide a cultural values context for examining the data from questions 3 and 4.

In all countries, consensus was reached after two rounds of the Delphi process. The replies from the respondents were content analyzed using Nvivo software. Frequently, repeated words were identified and coded. Points of agreement and disagreement were noted. Themes that are common were identified and frequency counts of agreement were noted.

In Round 2, participants were asked to rate the importance of the indicated responses from Round 1 for each question using a five-point Likert scale, where

1 equaled “relatively unimportant” and 5 equaled “very important”. Means for each response were computed by summing the ratings for each item across all participants and dividing by the number of respondents. The means for the five highest-rated responses are reported in the tables that follow.

4. Results

4.1 Cultural attributes that contribute to leader effectiveness

Respondents from the USA and Canada described being well educated as one of the most important cultural elements. Canadian respondents also felt social relationships and community building were important. Respondents from Barbados and Uganda

Leadership

211

AJEMS

4,2

212

Table I.

Cultural dimensions related to leader effectiveness gave responses such as values, beliefs, language, collaboration, and helping others.

Ugandans gave specific examples such as clans and tribes, and Barbadians felt religion was important. These and other aspects of culture that contribute to being an effective leader in their country are summarized in Table I. These aspects of culture will be used as a benchmark against which to examine the responses to Delphi questions 3, 4, and 6.

4.2 Words/terms used to describe an effective leader in the community

Table II summarizes the results concerning how respondents described an effective leader and indicates the mean values for the descriptive terms given. Commonalities in respondents’ descriptive terms included “inspirational/charisma”, which ranked among the top three descriptive terms for all countries except Uganda, for which the term was fourth in order of magnitude. “Honesty/integrity” was also used to describe effective leaders by participants from all four countries, all of whom rated this term among the top four descriptive terms in importance for describing an effective leader.

Other commonalities in respondents’ descriptive terms included being a visionary, which was deemed important for effectiveness by respondents from Uganda, the USA, and, to a lesser extent, Canada. Additionally, communication and listening skills were important attributes of an effective leader for respondents from Uganda, the USA and,

Uganda

Communities

Beliefs/values

USA

Being well educated

Religious beliefs/values

Different/unique Love of family

Languages, traditions, clans and tribes

Collaboration and generosity

Accommodative, welcoming, politeness

Respect for elders and leaders

Sense of community and giving back to others

Hard work/focus on meritocracy

Canada Barbados

Religious beliefs and behavior

Social behavior, relationships and interactions

Religion

Language

Importance of community building

Values, attitudes, beliefs, honoring traditions

Being well educated Helping one another

Morality/leading by example

Biblical way of leadership

Table II.

Words/terms used to describe an effective leader in the community

Uganda USA Canada Barbados

Honesty/integrity (4.80) Good communicator and listener (4.75)

Knowledgeable (4.75) Honest and trustworthy

(4.75)

Good communicator and listener (4.69)

Inspirational and charismatic (4.69)

Understanding (4.63)

Motivating and inspirational (4.63)

Persuasive and influential (4.63)

Visionary (4.50)

Respectful (5.00)

Inspirational and charismatic (4.88)

Honesty/trustworthy

(4.75)

Visionary (4.63)

Good communicator and listener (4.68)

Visionary (4.88)

Able to inspire/ charismatic (4.88)

Able to create an effective team (4.88)

Honest/virtuous

(4.75)

Leads by example

(4.75)

to a lesser extent, Canada; respondents from Barbados felt communication and listening skills were relatively unimportant for being an effective leader. Moreover, one characteristic that was relatively unimportant for being an effective leader that respondents from all four countries reported was being sensitive/caring/empathetic.

4.3 Words used to describe what effective leaders do

The results regarding how respondents described what an effective leader does are summarized in Table III. The average ratings received for each response are indicated in parentheses. The responses for this question exhibited more variance across countries regarding which actions were rated higher than other actions, compared to the responses summarized in Table II. Actions considered less important may or may not appear in Table III depending on their average ratings.

As shown in Table III, each country had a different leader action that was rated most important and indicative of what effective leaders do. For example, “inspires/empowers others” and “creative/innovates” received the highest ratings for Uganda;

“demonstrating competence” and “envisioning” were rated highest for the USA; being

“trustworthy/dependable” and “inspiring and empowering others” were rated highest for Canada; and “developing a vision and goals” was rated highest for Barbados. Of the responses given by respondents across all four countries that were rated as less important based on their mean scores, “communicating well” and “showing concern and empathy” were seen as less important for American, Barbadian, and Ugandan leaders to be effective.

“leading by example” and “building consensus” were less important actions for effective leaders in Canada.

4.4 Names of effective leaders (local, national/international)

A broad range of local, national, and international leaders were mentioned by participants from each of the countries. The leaders that the participants most frequently mentioned (Table IV) were Nelson Mandela, Barak Obama, Martin Luther

King, and Mahatma Ghandi. The Ugandan list included non-Africans such as Jack

Welch, Pope John Paul II, and Margret Thatcher as well as local and tribal leaders.

Respondents from Barbados, Canada and the USA identified leaders from the

Americas, such as Martin Luther King and Barak Obama, as well as local leaders: Errol

Barrow in Barbados, Pierre Elliott Trudeau in Canada, and Oprah Winfrey in the USA.

Leadership

213

Uganda USA Canada Barbados

Inspires/influences others (4.75)

Creative/innovates

(4.75)

Inspires a shared vision

(4.81)

Demonstrates competence/ leads by example (4.81)

Creates vision (4.69) Achieves results (4.75)

Takes action and achieves results (4.56)

Communicates well/ listens (4.56)

Guides/leads by example

(4.75)

Motivates others to achieve success (4.73)

Inspires/empowers others (4.75)

Consults with people

(4.71)

Motivates/encourages

(4.63)

Takes action and achieves results (4.50)

Leads by example

(4.25)

Develops a vision and goals (4.75)

Motivates others to perform effectively (4.71)

Leads by example (4.63)

Provides direction (4.63)

Inspires others to be better (4.50)

Table III.

What effective leaders do

AJEMS

4,2

214

Table IV.

Names of effective leaders

The leaders who were named as effective provided another way to look at the question of what makes a good leader. Nelson Mandela, an African, was clearly the favorite, named by 18 people across all countries. Barack Obama was a close second, named by

15 people (note that this was shortly after his election, and he had been in the news around the world). The words used to describe these people, who one might classify as

“great leaders” are both similar to, and different from, the previous descriptions of leaders and their attributes.

The words used to describe why these leaders were effective are presented in

Table V. Ugandan words included freedom fighter, principled, ability to bring people together, and ability to give or inspire hope. In Barbados respondents said visionary, charismatic, balanced and fair, selflessness, and proactive. In Canada, ability to bring people together, ability to give hope, community advocate, great orator and nonviolent were mentioned. For the USA, respondents said ability to mobilize and uplift people, use of non-violence, being principled, and being a servant leader accounted for the effectiveness of the persons named.

These results are discussed further in the next section and implications for management and further research are also examined.

5. Discussion

In summary, this study reports on an emic approach where participants defined the concepts in their own terms. These results provided data about the similarities and differences in respondents’ mental maps regarding culture, leadership and motivation.

On some points, the respondents from Barbados, Canada, and the USA differ from their

Uganda USA Canada Barbados

Nelson Mandela (4.83) Martin Luther King Jr

(5.00)

Martin Luther King Jr

(5.00)

Errol Walton Barrow

(5.00)

Mahatma Ghandi (4.86) Barack Obama (4.93) Nelson Mandela (5.00) Nelson Mandela (5.00)

Barack Obama (4.78) Nelson Mandela 4.69) Barack Obama (4.75) Mahatma Gandhi (5.00)

Martin Luther King Jr

(4.75)

Oprah Winfrey (4.64)

Pope John Paul II (4.67) Bill Clinton (4.00)

Pierre Elliott Trudeau

(4.75)

Mahatma Ghandi (4.55)

Barack Obama (4.75)

Owen Arthur (4.60)

Note: local/national/international

Table V.

Reasons leaders are effective

Uganda USA

Freedom fighter Ability to mobilize and uplift people

Principled individual Use of non-violence

Ability to bring people together

Ability to give/inspire hope

Fought for a cause

A person of principles

A unifier

Servant leader

Canada Barbados

Ability to bring people/ groups together for a cause

Ability to give (sow the seeds) of hope

Community advocate

Visionary

Charismatic

Balanced and fair

Great orator

Non violent

Selflessness and courageous

Proactive

Ugandan counterparts, while on others, Ugandan and Barbados respondents present similar ideas to each other and the USA and Canadian respondents have a contrasting view. The similarities and differences support the idea that culture is an important predictor of effective leadership style. Using the approaches that are effective in

Western countries in Africa is not likely to be effective. These results support the contention (Obiakor, 2005) that research needs to look at specific cultural elements and preferences before developing motivational tools for African people.

The results of the questions regarding leadership suggest that there are aspects of leadership that should be included in investigations of effective leaderships that are not obvious in the definition of leadership provided earlier in this paper. In Ugandan responses, we see that honesty/integrity is important, as are understanding and caring, being inspirational, and being knowledgeable. In Canada and the USA responses, education and knowledge were emphasized, and helping others and working with the community were also mentioned. In Barbados, helping others, setting an example and supporting followers were important leadership aspects, but power and prestige were seen as motivating leaders. Issues associated with community, helping others, humility and power are some of contrasts that stand out. In order to get at these characteristics in studies of leadership, survey instruments that include scales and items to measure these variables are needed.

5.1 Contributions of the research

In general, the results of this research are consistent with those of other studies that examined effective leadership in Africa, whereby the effective leader was seen as exhibiting qualities of caring, paternalistic, supportiveness and being interpersonally appealing (Newenham-Kahindi, 2009). This study has only begun to “scratch the surface” in uncovering similarities and differences in leader effectiveness across the African diaspora and in Africa itself. The present researchers believe that turning the spotlight on the African diaspora brings attention to particular groups that have been ignored in past research, and this represents one of the important contributions of the research project. Indeed, while there have been studies of other ethnic diaspora that compared cultures such as the Chinese diaspora (e.g. comparisons of Mainland

Chinese, American-born Chinese, Chinese in Singapore, Chinese in Hong Kong), this study is one of only a few to specifically target the African diaspora in North America and the Caribbean for comparisons with a country from Africa.

Another contribution of the study is the uncovering of cultural attributes that influence leader behaviors in the cultures of Uganda and the African diaspora in

North America and the Caribbean – such as religion, beliefs, and values; morality and leading by example; value on education; and language and traditions – that go beyond the cultural dimensions of the GLOBE project (House et al.

, 2004) or Hofstede’s (2001) work. Indeed, this point has been emphasized in a recently published article by

Dickson et al.

(2012) that takes an in-depth look at how leadership across cultures is conceptualized. These authors noted that cross-cultural research often relies on pre-determined cultural dimensions such as those developed by Hofstede and the

GLOBE project. Therefore, it is important to include other cultural dimensions beyond those of Hofstede and GLOBE that could help clarify important leadership characteristics. They note that “moving toward a more local understanding of culture and by taking more of an emic approach to the study of leadership in different

Leadership

215

AJEMS

4,2

216 regions will yield results that are more practical for organizations” (Dickson et al.

, 2012, p. 489). The present authors could not agree more with Dickson and his colleagues. The present study reflects the very approach that they advocate and also supports the conclusions of authors such as James (2008) and McFarlin et al.

(1999) who suggested that effective African leadership, as well as training and development for leaders, needs to include local culture and values.

5.2 Implications for research and practice

The research reported in this paper is preliminary and exploratory, which prevents us from drawing strong conclusions or generalizing beyond the present samples.

Nonetheless, we believe it provides a contribution to the literature and a basis on which we and others can build further research. As preliminary and exploratory research there are a number of limitations which are important, and which we want to bring to the readers’ attention.

The sample sizes for each of the countries in this project are small. Small sample sizes are not unusual in this type of qualitative research, especially using the Delphi approach.

Nevertheless, the results are limited to the opinions of a small group of people, and cannot be generalized to a wider group. In future research, we intend to broaden the sample to include a wider range of participants, include a wider range of countries from

Africa, and to include quantitative measures that will allow standardized comparisons across groups as well as provide the opportunity to have sufficient statistical power for statistical analyses that will examine proposed relationships.

The Delphi process is based on soliciting responses from experts/knowledgeable people. This approach provides input that is based on expertise and knowledge, and, at the same time, because of their expertise and knowledge, the respondents are likely to have beliefs and viewpoints that may be different from the average person. Again, we cannot consider the responses here to be generalizable to the broader populations, or to represent the thinking of the average person in the countries investigated.

The process used in this research is intentionally open ended, in order to tap into the respondents’ views, rather than imposing pre-determined ideas. This means that the responses may vary substantially, and it may be difficult to reach a sense of consensus.

In our responses, we found a large degree of agreement; thus, we are relatively comfortable in reporting the results. At the same time, we recognize that open-ended responses, such as these, can be influenced by a variety of factors, including even current news events.

We believe that the limitations identified here will be overcome in future research.

We have now tested the Delphi process in six countries (Kenya, Uganda, Ghana,

Barbados, Canada, and the USA) to make sure there is no misunderstanding of the procedure and to be sure that participants understand the questions. Unfortunately, key aspects of the data from Kenya and Ghana were not available for the preparation of this paper. As noted previously, further Delphi investigations will broaden the sample. This emic approach will be supported by focus groups. Quantitative survey measures can then be developed to make large-scale comparisons among countries.

The research presented has several implications for leaders, organizations, and society. First, leaders who are engaged in managing global virtual teams that may include persons from the countries represented in this study now have a baseline of leader attributes and characteristics considered important in the team

members’ home culture. Therefore, management of the team can be enhanced by becoming familiar with the important societal cultural elements of the members’ home culture. Second, organizational HRM practices such as training and development, designed to prepare persons who will interface with people from other cultures, can be informed by the results of the present study. Third, for those organizations that target certain communities within the African diaspora for marketing and sales purposes, understanding some of the subtleties of the targeted communities’ culture can help to better tailor the organization’s message such that it will be received appropriately.

Several unique cultural characteristics were uncovered in this study and these might be something that organizations and leaders need to pay attention to. Therefore, it is hoped that the current project provides the basis for further research, while also providing practical guidance for managers.

5.3 Summary

This paper describes an emic approach to define the concepts of culture, leadership and motivation, by participants in their own terms. This is intended to overcome the

Western bias identified by other scholars in most research. Results provide interesting ideas about the similarities and differences in respondents’ views. On some points, the respondents from Barbados, Canada, and the USA differed from their African counterparts, while on others, Ugandan and Barbadian respondents presented similar ideas while the USA and Canadian respondents took a different position. The similarities and differences identified support the idea that culture is an important predictor of effective leadership style. These results also support other studies (Obiakor, 2005), which concluded that specific cultural elements and preferences were relevant for understanding leadership among African people.

We believe that the results of this study are important in two aspects. First, they provide empirical evidence, adopting the blank page approach, of the cultural influences on leadership in an African country and among the African diaspora. Second, the results also provide a basis for developing further research studies. Indeed, we believe this study partially answers the critique of Takahashi et al.

(2012) who observed that relatively few qualitative studies of leadership exist in the international context. These authors suggested that understanding leadership phenomena in an international context can be aided if researchers take a triangulation approach that employed qualitative interviews, surveys, experimental manipulations, and archival organizational records. The LEAD research program intends such an approach. We anticipate that the results of further research will add substantially to the academic and managerial literature and knowledge base. In particular, we believe this research is significant because it avoids the Western bias of much research on Africa, through the use of the emic Delphi approach.

References

Baba, V.V., Galperin, B.L. and Lituchy, T.R. (1999), “Work and depression: a study of nurses in the Caribbean”, International Journal of Nursing , Vol. 36, pp. 163-169.

Baba, V.V., Tourigny, L., Wang, X., Lituchy, T. and Monserrett, S.I. (2010), “Stress among nurses: a multi-nation test of the demand-control-support model”, unpublished manuscript,

Concordia University, Montreal.

Baruch, L. (2001), Intangibles: Management, Measurement, and Reporting , Brookings Institution

Press, Washington, DC, p. 150.

Leadership

217

AJEMS

4,2

218

Beugre, C.D. and Offodile, O.F. (2001), “Managing for organizational effectiveness in sub-Saharan

Africa: a culture-fit model”, International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 12

No. 4, pp. 535-550.

Bewaji, J.A.I. (2003), “Leadership – a philosophical exploration of perspectives in African,

Caribbean and Diaspora polities”, Journal on African Philosophy , No. 2.

Blunt, P. and Jones, M.L. (1992), Managing Organizations in Africa , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin.

Blunt, P. and Jones, M.L. (1997), “Exploring the limits of Western leadership theory in East Asia and Africa”, Personnel Review , Vol. 26 Nos 1/2, pp. 6-23.

Bolden, R. and Kirk, P. (2009), “African leadership – surfacing new understandings through leadership development”, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 69-86.

Bruton, G.D. (2010), “Business and the world’s poorest billion – the need for an expanded examination by management scholars”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 24

No. 3, pp. 6-10.

CIA (2010), The world factbook , available at: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/geos/us.html

Cole, N.D. and Berengut, R.G. (2009), “Cultural mythology and global leadership in Canada”, in

Kessler, E.H. and Wong, D.J.M.J. (Eds), Cultural Mythology and Global Leadership , Edward

Elgar, Northampton, MA.

Corbin, A. (2009), Leadership and Cricket in the Caribbean , University of the West Indies, Cave

Hill.

Custer, R.L., Scarcella, J.A. and Stewart, B.R. (1999), “The modified Delphi technique: a rotational modification”, Journal of Vocational and Technical Education , Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 1-10.

Das, J., Do, Q.T., Shaines, K. and Srinivasan, S. (2009), “US and them: the geography of academic research”, Policy Research Working Paper 5152, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Dickson, M., Castano, N., Magomaeva, A. and Den Hartog, D. (2012), “Conceptualizing leadership across cultures”, Journal of World Business , Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 483-492.

( The ) Economist (2010), “They may be giants: a special report on banking in emerging markets”,

The Economist , May, p. 3.

Gramby-Sobukwe, S. (2005), “Africa and US foreign policy: contributions of the diaspora to democratic African leadership”, Journal of Black Studies , Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 779-801.

Grint, K. (2005), Public Sector Leadership , Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY.

Hale, J. (2004), “A contextualized model for cross-cultural leadership in West Africa”, paper presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, Regent University.

Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and

Organizations Across Nations , 2nd ed., The Free Press, New York, NY.

Horwitz, F., Kamoche, K. and Chew, I. (2002), “Looking east: diffusing high performance work practices in the Southern Afro-Asian context”, International Journal of Human Resource

Management , Vol. 13 No. 7, pp. 1019-1041.

House, R., Wright, N. and Aditya, R. (1997), “Cross-cultural research on organizational leadership: a critical analysis and a proposed theory”, in Early, P.C. and Erez, M. (Eds),

New Perspectives on International Industrial/Organizational Psychology , New Lexington

Press, San Francisco, CA.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. and Dorfman, P. (2002), “Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: an introduction to project GLOBE”, Journal of World

Business , Vol. 37, pp. 3-10.

House, R., Hanges, P., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. and Gupta, V. (2004), Culture, Leadership and

Organizations, The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies , Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Hsu, C. and Sandford, B. (2007), “The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus”, Practical

Assessment, Research and Evaluation , Vol. 12 No. 10.

Jackson, T. (2004), Management and Change in Africa: A Cross Cultural Perspective , Routledge,

London.

Jago, A.G. (1982), “Leadership: perspectives in theory and research”, Management Science , Vol. 28

No. 3, pp. 315-336.

James, R. (2008), “Leadership development inside-out in Africa”, Nonprofit Management and

Leadership , Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 359-3753.

Kamoche, K., Debrah, Y., Horwitz, F. and Muuka, G.N. (2004), Managing Human Resources in

Africa , London, Routledge.

Kopelman, R., Brief, A. and Guzzo, R. (1990), “The role of climate and culture in productivity”, in

Schneider, B. (Ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture , Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Kotter, J.P. (1988), The Leadership Factor , The Free Press, New York, NY.

Linstone, H.A. and Turoff, M. (Eds) (1975), The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications ,

Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA.

Lituchy, T., Punnett, B.J., Ford, D. and Jonsson, C. (2009), “Leadership effectiveness in Africa and the Diaspora”, paper presented at the Eastern Academy of Management International

Proceedings, Rio, Brazil.

Lord, R. and Maher, K. (1991), Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and

Performance , Unwin-Everyman, Boston, MA.

Lord, R., Foti, R. and De Vader, C. (1984), “A test of leadership categorization theory: internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions”, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , Vol. 34, pp. 343-378.

McClelland, D. (1985), Human Motivation , Scott-Foresman, Glenview, IL.

McFarlin, D.B., Coste, E.A. and Mogale-Pretorius, C. (1999), “South African management development in the twenty-first century: moving toward an Africanized model”, Journal of

Management Development , Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 63-78.

Mangaliso, M.P. (2001), “Building competitive advantage from Ubuntu: management lessons from South Africa”, Academy of Management Executive , Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 23-32.

Mathauer, I. and Imhoff, I. (2006), “Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools”, Human Resources for Health , Vol. 4

No. 24.

Mbigi, L. (2000), In Search of the African Business Renaissance , Knowledge Resources,

Randburg.

Mbigi, L. and Maree, J. (1995), Ubuntu: The Spirit of African Transformation Management ,

Knowledge Resources, Randburg.

Mittal, R. and Dorfman, P. (2012), “Servant leadership across cultures”, Journal of World

Business , Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 555-570.

Mohan, G. and Zack-Williams, A.B. (2002), “Globalization from below: conceptualizing the role of the African diasporas in Africa’s development”, Review of African Political Economy ,

Vol. 29 No. 92, pp. 211-236.

Newenham-Kahindi, A. (2009), “The transfer of Ubuntu and Indaba business models abroad – a case of South African multinational banks and telecommunication services in Tanzania”,

International Journal of Cross Cultural Management , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 87-108.

Leadership

219

AJEMS

4,2

220

Nurse, L. and Devonish, D. (2008), “Worker participation in Barbados: contemporary practice and prospects”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 19 No. 10, pp. 1911-1928.

Obiakor, F.E. (2005), “Building patriotic African leadership through African-centered education”,

Journal of Black Studies , Vol. 34 No. 3, pp. 402-420.

Paglis, L.L. and Green, S.G. (2002), “Leadership self-efficacy and managers’ motivation for leading change”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 215-235.

Punnett, B.J. (2008), “Management in developing countries”, in Wankel, C. (Ed.), 21st Century

Management , Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 190-199.

Punnett, B.J. and Greenidge, D. (2009), “Cultural mythology and global leadership in the

Caribbean Islands”, in Kessler, E.H. and Wong-MingJi, D.J. (Eds), Cultural Mythology and

Global Leadership , Edward Elgar, Northampton, MA.

Punnett, B.J. and Nurse, L. (2002), “Management research on the English-speaking Caribbean: toward a research agenda”, Journal of Eastern Caribbean Studies , Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 1-37.

Punnett, B.J., Corbin, A. and Greenidge, D. (2007), “Assigned goals and task performance in a

Caribbean context: extending management research to an emerging economy”,

International Journal of Emerging Markets , Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 215-235.

Punnett, B.J., Dick-Forde, E. and Robinson, J. (2006), “Effective management and culture: an analysis of three English-speaking Caribbean countries”, Journal of Eastern Caribbean

Studies , Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 44-71.

Schein, E. (1992), Organizational Culture and Leadership: A Dynamic View , 2nd ed., Jossey-Bass,

San Francisco, CA.

Shamir, B., House, R.J. and Arthur, M.B. (1993), “The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: a self-concept based theory”, Organization Science , Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 577-594.

Smith, B. (2003), “Worldview and culture: leadership in sub-Saharan Africa”, New England

Journal of Public Policy , Vol. 19 No. 1, p. 243.

Spears, L. (Ed.) (1998), Insights on Leadership: Service, Stewardship, Spirit, and Servant

Leadership , Wiley, New York, NY.

Takahashi, K., Ishikawa, J. and Kanai, T. (2012), “Qualitative and quantitative studies of leadership in multinational settings: meta-analytic and cross-cultural reviews”, Journal of

World Business , Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 530-538.

Thomas, A. (1996), “A call for research in forgotten locations”, in Punnett, B.J. and

Shenkar, O. (Eds), Handbook for International Management Research , Blackwell,

Cambridge, MA, pp. 485-506.

Thomas, A., Shenkar, O. and Clarke, L. (1994), “Globalization of our mental maps: evaluating the geographic scope of JIBS coverage”, Journal of International Business Studies , Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 675-686.

Tsui, A.S. (2004), “Contributing to global management knowledge: a case for high quality indigenous research”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 491-513.

Tsui, A.S. (2006), “Contextualization in Chinese management research”, Management and

Organization Review , Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 1-13.

Walumbwa, F.O., Orwa, B., Wang, P. and Lawler, J.J. (2005), “Transformational leadership, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction: a comparative study of Kenyan and US financial firms”, Human Resource Development Quarterly , Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 235-256.

Wambu, O. and Githongo, J. (2007), Under the Tree of Talking: Leadership for Change in Africa ,

Counterpoint (The Cultural Relations Think-Tank of the British Council), London.

Wanasika, I., Howell, J., Littrell, R. and Dorfman, P. (2011), “Managerial leadership and culture in sub-Saharan Africa”, Journal of World Business , Vol. 46, pp. 234-241.

Werner, S. (2002), “Recent developments in international management research: a review of

20 top management journals”, Journal of Management , Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 277-305.

Wheatley, M. (2001), “Restoring hope to the future through critical education of leaders”, Journal for Quality and Participation , Vol. 24 No. 3, pp. 46-49.

(The) World Bank (2010), available at: http://ddp-ext.worldbank.org/ext/ddpreports/

ViewSharedReport?&CF ¼ &REPORT_ID ¼ 9147&REQUEST_TYPE ¼ VIEW ADVANCED

&HF ¼ N/CPProfile.asp&WSP ¼ N (accessed 7 October 2010).

Yukl, G.A. (2005), Leadership in Organizations , 6th ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Further reading

Amabile, T.M. (1993), “Motivational synergy: towards new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 185-201.

Punnett, B.J., Greenidge, D. and Ramsey, J. (2007), “Job attitudes and absenteeism: a study in the

English speaking Caribbean”, Journal of World Business , Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 214-227.

About the authors

Dr Terri R. Lituchy (PhD, University of Arizona) is an Associate Professor of International

Management at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. She has taught at the undergraduate and graduate levels around the world including the USA, Mexico, Caribbean, Argentina, France, the UK, Czech Republic, Japan, China, Thailand and Malaysia. Her research interests are in cross-cultural issues in organizations including cultures effect on work stress and absenteeism, negotiation and conflict; international issues of service firms, women in international business and international entrepreneurship. In addition to the book Successful Professional Women of the

Americas (Elgar Publishing, 2006), recent articles appear in International Journal of Cross

Cultural Management, JET-M, The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small

Business, Leadership Quarterly, Career Development International, Women in Management

Review, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Canadian Journal of Regional Sciences and

Journal of Organizational Behavior.

She is currently editing books on Management in Africa

(Routledge Publisher, forthcoming) and Gender and Counterproductive Work Behaviors (Elgar

Publishing, in press). Terri R. Lituchy is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: terrilituchy@yahoo.com

David Ford (PhD, University of Wisconsin-Madison) is Professor of Organizational Studies,

Strategy and International Management at the University of Texas at Dallas. His research interests include leadership development in transition economies; job insecurity, perceptions of procedural justice, and career attitudes during economic downturns; global team leadership and effectiveness; and cross-cultural studies of job stress, coping, and perceived organizational support. Dr Ford has also held academic appointments at UCLA, Purdue University, Michigan

State University, and Yale University. Through his membership in the Society of International

Business Fellows, he continues to develop his research and business interests in international business development. He has traveled extensively internationally and is engaged in several cross-cultural research projects involving Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

He has received numerous awards, including Outstanding Alumnus Award from Iowa State

University, Distinguished Service Citation from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a

Commission in the Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels. His publications have appeared in academic journals such as Academy of Management Review, Applied Psychology:

An International Review, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Cross cultural Management:

Leadership

221

AJEMS

4,2

222

An International Journal, Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, Group and Organization

Management, International Journal of Human Resource Management, International Journal of

Intercultural Relations, Journal of International Management Studies, Journal of Applied

Behavioral Science, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Asia Business Studies, Journal of

International Management, Journal of Management and Organizational Behavior and Human

Performance.

Betty Jane Punnett is Professor of International Business and Management at Cave Hill,

University of the West Indies. She has lived and worked in the Caribbean, Canada, Europe, Asia, and the USA. Her major research interests are culture and management and she is currently working on several research projects in this field, including leadership and motivation in Africa and the diaspora. She holds a PhD in International Business (New York University), an MBA

(Marist College) and a BA (McGill University). She has published over 50 academic papers in a wide array of international journals, and several books – including The Handbook for

International Management Research , International Perspectives on Organizational Behavior and

Human Resource Management , Experiencing International Business and Management and

Successful Professional Women of the Americas . She is currently working on a Routledge book,

Managing in Developing Countries and co-editing a special issue of the International Journal of

Cross Cultural Management on Caribbean metaphors and management. She has received a number of awards and research grants, including a grant from the Ford Foundation and serving as a Fulbright Scholar.

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints