Globalization Versus Normative Policy: A Case Study on the Failure

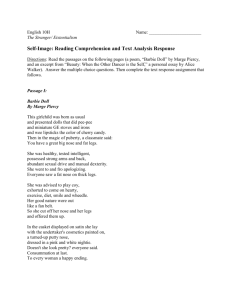

advertisement