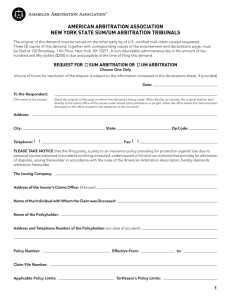

Pre-Dispute Consumer Arbitration Clauses

advertisement