give us your weary but not your battered: the department of

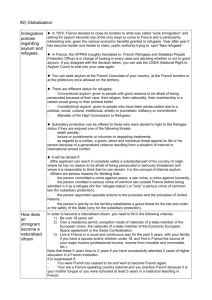

advertisement

\\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt unknown Seq: 1 19-JAN-12 14:13 GIVE US YOUR WEARY BUT NOT YOUR BATTERED: THE DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, POLITICS AND ASYLUM FOR VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Natalie Rodriguez* I. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A. Asylum Law and Why it Fails Battered Women . . . . 1. The Origins of Asylum Law in the United States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . II. ASYLUM ADJUDICATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . III. THE POLITICAL AND LEGAL JOURNEY FOR BATTERED WOMEN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A. The Clinton Administration: Hope for Battered Women Seeking Asylum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B. The Bush Administration: A Step Back for Battered Women . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C. A Renewed Promise: The Obama Administration . . IV. THE STATUS OF ASYLUM FOR BATTERED WOMEN AND RECOMMENDATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A. A Lesson from the United State’s response to China’s “One Child Policy” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B. The Obama Administration Should to Amend The Refugee Act . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C. The Obama Administration Should Promulgate Joint Regulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 318 319 R 319 322 R 323 R 325 R 329 332 R 334 R 334 R 337 R 339 R * J.D., Southwestern Law School, 2012; The author is grateful to Professors Austen Parrish and Alison Kleaver for their insights and guidance during the development of this article. The author would also like to thank the Southwestern Journal of International Law Board and Staff for the countless hours spent on producing this issue. Finally, the author would like to acknowledge that this article would not be possible without the unyielding encouragement and support of her family, above all, her husband, Jesse A. Rodriguez and children, Elijah and Emma. 317 R R R \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 318 unknown Seq: 2 19-JAN-12 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 14:13 [Vol. 18 V. SILENCING THE CRITICS: WHY THE FLOODGATES ARGUMENT FAILS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A. Statistics Say Otherwise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B. The Burden Remains High . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C. Sending a Clear Message . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . VI. CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 340 341 342 343 345 “And to all those who have wondered if America’s beacon still burns bright: . . . we proved once more that true strength of our nation comes . . . from the enduring power of our ideals: democracy, liberty, opportunity and unyielding hope.”—President-Elect Barack Obama1 I. INTRODUCTION Under the Obama Administration, there is, once again, a shift in immigration policy, especially for granting battered women asylum. Until 2009, battered women were continuously denied refugee protection. Asylum adjudicators consistently misinterpreted the term “particular social group,” one of five refugee categories under the Refugee Act.2 In 2009, however, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) filed a supplemental brief with the Department of Justice (DOJ) on behalf of a battered woman. The brief argued that battered women should be granted asylum under certain circumstances. This development is a step in the right direction, but it is not enough because whatever progress has been made under the Obama Administration could be halted and even reversed with any future administration. President Obama and Congress must work in unison to amend the Refugee Act of 1980 (Refugee Act) and formally recognize battered women as members of a “particular social group” for asylum purposes. Additionally, the DHS and DOJ, the two agencies responsible for adjudicating asylum claims, must also issue joint regulations implementing this change. If this is not done, asylum law adjudicators will continue to produce inconsistent results leading to an unjust and inefficient system. Part I of this Comment will present a brief history of refugee and asylum law in the United States. Specifically, it will explain the adjudication process and why this process fails to produce consistent re1. Barack Obama, President-Elect, Victory Speech (Nov. 4, 2008) (transcript available at http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=96624326) [hereinafter Speech]. 2. Refugee Act of 1980, PL 96 212, 96th Cong. 8 U.S.C. § 1101 (2006) [hereinafter Act]; see Edward M. Kennedy, The Refugee Act of 1980, 15 INT’L MIGRATION REV. 141 (1981). R R R R R \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 3 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 319 sults. Part II highlights the evolution of the term “particular social group” and how this category has provided gender-based claims an avenue for asylum. Part III will demonstrate how politics has directly impacted and encouraged disparate adjudication as evidenced by the stories of two battered women who came to the United States seeking asylum. Part IV will illustrate, through a case study of China’s “One Child Policy,” that the appropriate response to the current inefficient system is to immediately pass legislation and joint-regulations. Finally, Part V rebuts the argument that granting asylum to battered women will open the floodgates. This comment concludes that, unless the Obama Administration’s current policy is formally adopted and codified, battered women will continue to face an inconsistent and uncertain future in asylum adjudication. A. Asylum Law and Why it Fails Battered Women 1. The Origins of Asylum Law in the United States In 1945, when the United States signed the United Nations Charter (Charter), it extended “its longstanding recognition of an ‘international minimum standard’ to include all human beings rather than just aliens.”3After Congress ratified the Charter, it served as the “supreme law of the land.”4 Shortly thereafter, Congress also ratified the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees5 and its 1967 Protocol6 (collectively, “Convention”).7 According to the Convention, a refugee is any individual who “owing to [a] wellfounded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, . . . is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the 3. Richard B. Lillich, Invoking International Human Rights Law in Domestic Courts, 54 U. CEN. L. REV. 367, 371 (1985). Since then, the United States has committed itself to several other international human rights instruments: Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, and the American Convention on Human Rights of 1969. With an increase in immigration laws, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1952 and transferred all existing immigration laws to that title. It is a complicated and intertwined set of laws that also embodies the country’s international commitments. 4. Id. However, domestic courts have interpreted the human rights clause of the UN Charter as non-self executing clauses. 5. 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, 189 U.N.T.S. 150 [hereinafter Convention]. 6. 1967 United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Jan. 31, 1967, 19 U.S.T. 6223, 606 U.N.T.S. 267. 7. Lillich, supra note 3, at 386. By contrast, domestic courts interpret containing self-executing provisions. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 320 unknown Seq: 4 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 protection of that country.”8 Once refugee status is acquired, the Convention provides that a member state to the Convention cannot return the refugee to the “persecuting” country from which he fled.9 In 1980, Congress passed its first substantial piece of refugee reform, the Refugee Act.10 The Refugee Act symbolized the United States’ “commitment to . . . refugees around the world” and embodied language similar to the language used by the Convention.11 Most significantly, it created an asylum provision for the first time in immigration law: if an individual qualifies for refugee protection and applies for such protection at or after port of entry into the United States, he or she is eligible for asylum.12 Despite Congress’ intention that the Refugee Act mirror the protections afforded to refugees under the Convention, adjudicators have restrictively interpreted the language of the Refugee Act. Instead, domestic courts13 have used the Convention as merely a “policy backdrop” during its quest to interpret the language of the Refugee Act.14 2. Qualifying for Asylum The Refugee Act’s requirements can be parsed into four separate elements. First, the applicant must prove that they are afraid of persecution.15 Second, this fear of persecution must be well-founded.16 Third, the persecution feared must be on account of one of the five recognized protected categories.17 Lastly, the applicant, because of this fear, is “unable or unwilling to return to his country of nationality or to the country in which he last habitually resided.”18 As to the first element, arriving at a uniform and consistent definition and interpretation of the term “persecution” has been challenging process adjudicators because neither the Refugee Act, nor any of its accompanying regulations explicitly define the term.19 Courts have, 8. Convention, supra note 5, at 152. 9. Lillich, supra note 3, at 386. 10. See Kennedy, supra note 2, at 141. 11. Id. at 142. 12. Id. at 150. 13. Throughout this Comment, the word “court” includes the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) unless specified otherwise. 14. See Lillich, supra note 3, at 388. 15. Matter of Acosta,,19 I. & N. Dec. 211, 233 (B.I.A. 1985), overruled in part by In re Mogharrabi,19 I. & N. Dec. 439 (B.I.A. 1987). 16. Id. at 213. 17. Id. 18. Id. 19. National Immigrant Justice Center, Basic Procedural Manual for Asylum Representation Affirmatively and in Removal Proceedings, ASYLUMLAW.ORG, at 9-10, available at http://www. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 5 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 321 however, interpreted this term broadly.20For example, in Desir v. Ilchert, the Ninth Circuit defined “persecution” as “the infliction of suffering or harm upon those who differ (in race, religion or political opinion) in a way that is regarded as offensive.”21 This definition includes non-life threatening abuse.22 The only limitation is that the persecution must be at the hands of the government itself or by a group the government is unable or unwilling to control.23 Next, an applicant’s fear of persecution must be well founded. As with the first element, courts have interpreted this requirement broadly. The standard used is whether the applicant’s fear is such that “a reasonable person in the same or similar circumstances as the applicant would also fear persecution.”24 To meet this standard, an applicant must prove the following: “(1) the alien must possess a belief or characteristic that a persecutor seeks to overcome in others by means of punishment of some sort; (2) the persecutor is already aware, or could . . . become aware, that the alien possesses this belief or characteristic; (3) the persecutor has the capability of punishing the alien; and (4) the persecutor has the inclination to punish the alien.”25 Courts analyze this requirement using a “common sense” framework.26 Third, an applicant must also prove that his persecution is on account of his membership in one of the five protected classes, often referred to as the “nexus” element.27 The five recognized protected classes are race, religion, nationality, political thought and membership in a particular social group. Here, the question is whether the applicant’s membership in any of the classes was “at least one central reason” for the persecution.28 Courts generally recognize that there is a nexus for the categories of race, religion, and nationality.29 For the asylumlaw.org/docs/united_states/MIHRC_manual_200506.pdf [hereinafter Manual] (last visited Sep. 18, 2011). 20. Id. 21. Desir v. Ilchert, 840 F.2d 723, 727 (9th Cir. 1988) (quoting Kovac v. INS, 407 F.2d 102, 107 (9th Cir. 1969)). 22. Manual, supra note 19, at 9. 23. Id. at 10. 24. In re Mogharrabi, 19 I. & N. Dec. 439, 445 (B.I.A. 1987). 25. Id. at 446 (removing the word ‘easily’ from the second element as provided by Matter of Acosta, supra note 15). 26. Id. at 445. 27. Act, supra note 2, at §1101(a)(42)(A). 28. Manual, supra note 19 at 11 n.1. “The REAL ID Act (P.L. 109-13) added the ‘one central reason’ burden of proof to asylum claims. Therefore, this burden only applies to asylum applications filed on or after May 11, 2005.” Id. 29. Id. at 12. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 322 unknown Seq: 6 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 last two categories, however, the nexus requirement is quite difficult to prove and is far more controversial.30 To establish that a nexus exists between persecution and the individual’s political thoughts, the applicant must prove that the harm would not have been inflicted had the individual not held his political opinion.31 The nexus requirement for persecution based on membership in a particular social group is discussed below in Section II. Finally, an asylum applicant must show they could not avoid further persecution by simply relocating within his home country.32 Initially, the government agency has the burden of showing that “under the circumstances, it would have been reasonable for the applicant to do so.”33 If this showing is made, the burden switches to the applicant to negate that finding.34 There are a number of factors that are considered in this final step, such as “social and cultural constraints, age and health, and social and familial ties.”35 This element is one of the most difficult elements for an asylum applicant to satisfy because it requires the applicant provide a strong evidentiary record that demonstrates he has exhausted all other options within his home country.36 II. ASYLUM ADJUDICATION Immigration enforcement has gone through a myriad of changes and both the DHS and the DOJ adjudicate asylum claims. Each agency, however, has its own set rules for interpreting the Refugee Act.37 Initially, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was responsible for administering and enforcing immigration laws.38 Then in 1940, it was moved from the Department of Labor to the DOJ.39 In 2002, President George W. Bush established the DHS40 and the fol30. See id. 31. Brief for Respondents at 22, In reL.R., (B.I.A. 2009), available at http://cgrs.uchastings. edu/pdfs/Redacted%20DHS%20brief%20on%20PSG.pdf [hereinafter 2009 Brief]. 32. Id. at 27. 33. Id. 34. See id. 35. Id. 36. REGINA GERMAIN, Asylum Primer 32, 90-92 (6th ed. 2010). 37. 8 C.F.R. pt. 1; 8 C.R.F. pt. 1001. 38. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service [INS], NATIONAL ARCHIVES, http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/085.html (last visited Dec. 15, 2010). 39. Id. 40. Homeland Security Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-296, 117 Stat. 745 (enacted Nov. 25, 2002). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 7 19-JAN-12 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 14:13 323 lowing year, many of INS’s immigration functions were transferred to it.41 One agency within DHS is the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, whose asylum officers are currently responsible for adjudicating affirmative asylum claims.42 The DOJ, however, remained significantly powerful due to the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which consisted of immigration judges and the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) who collectively were in charge of administering and reviewing immigration laws.43 In practice, the Executive Office for Immigration Review not only reviews, but often also overturns DHS decisions.44 As a result, it is common for an individual who initially affirmatively applied to find herself in a removal proceeding fighting a defensive asylum application before the Executive Office for Immigration Review.45 An applicant may face drastically different sets of policies that often lead to conflicting or inconsistent results. III. THE POLITICAL WOMEN AND LEGAL JOURNEY FOR BATTERED Recently, battered women have been able to define themselves successfully as members of a particular social group and prove that they suffered persecution on account of such membership. This change, unfortunately, came after years of inconsistent application and interpretation of what constitutes a “particular social group.” The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) points out that this category has the “least clarity and it is not defined by the [Convention] itself.”46 It proposed that adjudicators interpret the term to include individuals who “share a common characteristic other than their risk of being persecuted, or who are perceived as a group by society” to possess a common characteristic, 41. History: Who became Part of the Department?, DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/history/editorial_0133.shtm (last visited Dec. 15, 2010). With the transfer, INS seized to exist. Instead the majority of its functions are performed by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services of the Department of Homeland Security. 42. Id. (Explaining that the other two are the U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.). 43. EOIR at a Glance, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, http://www.justice.gov/eoir/press/ 2010/EOIRataGlance09092010.htm (last visited Dec. 15, 2010). 44. Id. 45. Manual, supra note 19, at 9. 46. UN Refugee Agency, GUIDELINES ON INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION: “Membership of a particular social group” within the context of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES (UNHCR), 2 (May 7, 2002), http://www.unhcr.org/3d58de2da.html [hereinafter GUIDELINES]. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 324 unknown Seq: 8 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 respectively named the “immutability” approach and the “external perception” approach.47 Here, in the United States, there is a split between those two prevailing approaches.48 The “immutable” approach is generally used for gender-based asylum claims. But, even then, adjudicators do not interpret either approach to fully embrace gender as a recognized characteristic. In Matter of Acosta, the BIA, following UNHCR’s guidelines, interpreted the term broadly and simply required that there be a “shared immutable characteristic” between the members.49 It specifically announced that a “shared characteristic might be innate such as sex.”50 It also stated that deciding what the qualifying characteristic is “remains to be determined on a case-by-case basis.”51 Unfortunately, subsequent courts have seized this latter language as controlling. Those who claim to use the Acosta approach in actuality require much more than Acosta ever intended, and instead have turned it into an “immutable shared characteristic plus” approach.52 Then, in 1996, the BIA further paved the way for gender-based asylum claims in In re Kasinga.53 A young 19-year-old Togo native fled her country for fear of forced female genital mutilation.54 Young girls customarily underwent this procedure by the age of fifteen.55 The BIA stated that “gender-based, or gender-related, asylum claims within the ‘membership in a particular social group’ construct . . . [are] entirely appropriate and consistent with the developing trend of juris47. Id. at 2-3. 48. In re Acosta, 19 I. & N. Dec. 211, 233 (B.I.A. 1985), overruled in part by In re Mogharrabi, 19 I. & N. Dec. 439 (B.I.A. 1987). (“[W]e interpret the phrase ‘persecution on account of membership in a particular social group’ to mean persecution that is directed toward an individual who is a member of a group of persons all of whom share a common, immutable characteristic.”) and Gomez v. I.N.S., 947 F.2d 660, 664 (2d Cir. 1991) (“A particular social group is comprised of individuals who possess some fundamental characteristic in common which serves to distinguish them in the eyes of a persecutor-or in the eyes of the outside world in general.”). 49. Acosta, 19 I. & N. Dec. at 233. 50. Id. 51. Id. 52. See In re Kasinga, 21 I. & N. Dec. 357, 365 (B.I.A. 1996) (“In the context of this case, we find the particular social group to be the following: young women of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu Tribe who have not had FGM, as practiced by that tribe, and who oppose the practice.”); Mohammed v. Gonzales, 400 F.3d 785, 797 (9th Cir. 2005) (“Few would argue that sex or gender, combined with clan membership or nationality, is not an ‘innate characteristic,’ ‘fundamental to individual identit[y].’ ”). 53. Kasinga, 21 I. & N. Dec. at 358. 54. Id. 55. Id. (stating that Kasinga avoided the procedure because her wealthy and influential father opposed the practice, but after her father died, her aunt married her off and made preparations for Kasinga to undergo the procedure). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 9 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 325 prudence in the United States and Canada as well as with international norms.”56 The BIA also noted that this type of persecution satisfies the “on account of” requirement because female genital mutilation “has been used to control woman’s sexuality” and is also “characterized as a form of ‘sexual oppression’ that is ‘based on the manipulation of women’s sexuality in order to assure male dominance and exploitation.’”57Kasinga, therefore, was one of the first cases that successfully used gender to satisfy the Acosta test. However, because the court defined the group as “[y]oung women who are members of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu Tribe of northern Togo who have not been subjected to the tribal practice of female genital mutilation, and who oppose the practice,” the BIA applied the test much more strictly than Acosta required.58 As the stories of R.A. and L.R.59will illustrate, this additional burden had a significant impact on the adjudication of asylum claims brought by victims of domestic abuse. A. The Clinton Administration: Hope for Battered Women Seeking Asylum Since Kasinga, victims of domestic abuse have also tried to gain asylum protection as members of a particular social group. R.A. is a Guatemalan woman who endured more then ten years of violence and torture from her husband.60 During this time, her husband dislocated her jaw because her menstrual period was late and then “kicked her violently in her spine . . . [w]hen she refused to abort her 3-to 4month-old fetus.”61 He often brutalized her “whenever he felt like it,” even in public.62 On one occasion, he caused her to bleed “severely for 8 days . . . [when] he kicked [her] in her genitalia, apparently for no reason.”63 R.A.’s husband also raped her repeatedly; “[h]e would beat her before and during the unwanted sex . . . threaten her with 56. Id. at 377. 57. Id. at 366-67. 58. Sarah Siddiqui, Note, Membership in a Particular Social Group: All Approaches Open Doors for Women to Qualify, 52 ARIZ. L. REV. 505, 515 (2010). 59. Asylum captions only contain the abbreviations of the applicant’s name due to the high sensitivity of the claims. See, e.g., REGINA GERMAIN, ASYLUM PRIMER 200 (6th ed. 2010). However, R.A.’s name has been released through the media; she is Rodi Alvarado. See, e.g., Karen Musalo, Matter of R-A-: An Analysis of the Decision and its Implications, 76 INTERPRETER RELEASE no. 30, 1177, 1178 (1999). L.R.’s name has not been made public. 60. In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. 906, 908 (B.I.A. 2001), remanded, 23 I. & N. Dec. 694 (B.I.A. 2005), stay lifted, 24 I. & N. Dec. 629 (B.I.A. 2008). 61. Id. 62. Id. 63. Id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 326 unknown Seq: 10 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 death . . . [and] passed on a sexually transmitted disease . . . from his sexual relations outside their marriage.”64 Yet none of this compared to the pain she suffered “when he forcefully sodomized her.”65 When she did protest, her husband would tell her”you’re my woman, you do what I say.”66 No matter where she fled within Guatemala, her husband would find her, and this only worsened the intensity of his abuse.67 Her husband constantly reminded her that “calling the police would be futile” because of his military connections.68 She defiantly contacted the police on two separate occasions, but no one came to her aid.69 When she was finally given the opportunity to appear before a Guatemalan judge, his response to her was “that he would not interfere in domestic disputes.”70 R.A. was unable to secure assistance from the Guatemalan government.71 As a result, R.A. was forced to flee from Guatemala and seek protection in the United States.72 In September 1996, an immigration judge granted R.A. asylum.73 The immigration judge found R.A.’s claim credible; she proved that she had suffered past persecution and that the “Guatemalan Government was either unwilling or unable to control [her] husband.”74 Additionally, the immigration judge held that “Guatemalan women who have been involved intimately with Guatemalan male companions, who believe that women are to live under male domination . . . [are] members of [a particular social group and] are targeted for persecution by the men who seek to dominate and control them.”75 R.A.’s victory, however, was short-lived. The then-INS immediately appealed the decision and argued that the immigration judge incorrectly interpreted the term “particular social group.”76 The 64. Id. 65. Id. 66. In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. at 908. 67. Id. at 908-09. 68. Id. at 909. 69. Id. 70. Id. 71. See In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. at 909. 72. Id. 73. Id. at 907. 74. Id. at 911. 75. In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. at 911.(“The Immigration Judge further found that, through the respondent’s resistance to his acts of violence, her husband imputed to the respondent the political opinion that women should not be dominated by men, and he was motivated to commit the abuse because of the political opinion he believed her to hold.”). 76. See, e.g., Karen Musalo, Matter of R-A-: An Analysis of the Decision and its Implications, 76 INTERPRETER RELEASE no. 30, 1177, 1181 (1999). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 11 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 327 government’s position was that R.A. was not abused as part of a larger social group, but rather was abused because her husband was a violent man.77 The BIA agreed with the INS finding that R.A., although clearly a victim of horrible domestic abuse, was unable to define herself as a member of a particular social group as recognized by refugee law.78 Additionally, even assuming arguendo that she was a member of a particular social group, she was unable to establish that she was persecuted on account of her membership in the group.79 The BIA found that R.A.’s claimed social group failed both because it did not have “a voluntary associational relationship” and she was unable to show “whether anyone in Guatemala perceived this group to exist in any form whatsoever.”80 The BIA explained that “the term ‘particular social group’ is to be construed in keeping with the other four [categories]” which are all recognized as such groups by society.81 Here, R.A. did not show that her claimed group was “recognized and understood to be a societal faction . . . within Guatemala [nor] . . . that the victims of spous[al] abuse view[ed] themselves as members of this group [or] . . . that their male oppressors [saw] their victimized companions as part of this group.”82 More importantly, because she failed to show that her claimed group was perceived as a social group, she was unable to sufficiently show that her husband persecuted her on account of that group, especially when all the evidence presented indicated that she was his only victim.83 The court distinguished Kasinga by stating that although Kasinga’s fear stemmed from threats by her aunt and husband, there was sufficient evidence that female genital mutilation was so pervasive throughout the country that either she or her family would be stigmatized if she did not undergo the procedure.84 R.A., however, was unable to prevail and show that domestic violence was either pervasive or encouraged in Guatemala as “societally important.”85 The trend in asylum adjudication is highly influenced by politics. President Bill Clinton’s position on immigration has been described as 77. did not 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85. R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. at 911 (“The Service also contends that the respondent’s husband persecute the respondent because of an imputed political opinion.”). Id. at 920, 927-28. Id. at 920. Id. at 918. Id. In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. at 918. Id. at 918-20. Id. at 924. Id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 328 unknown Seq: 12 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 one of “the most long lasting imprints he leaves on America.”86He believed that immigrants played a role in the nation’s proud cultural diversity and that “those who argue against immigration” should be repudiated for hiding behind a “thinly veiled pretext for discrimination.”87 In December 2000, as a direct response to the BIA’s decision in R.A., President Clinton directed the DOJ to propose new regulations that would amend the INS guidelines for establishing asylum eligibility and alleviate the myriad of inconsistencies in case law interpreting the term “particular social group.”88 The proposed rules codified Acosta and provided significant clarification.89 Most importantly, the DOJ emphasized that under certain circumstances, both gender and “marital status could be considered immutable.”90 However, the DOJ warned that this new rule could not be used to define a particular social group by alleging the same harm the applicant claimed as persecution.91 The DOJ also refused to adopt a “categorical rule” that every victim of domestic violence automatically receives a presumption that the nexus element is met.92 Notwithstanding these warnings, the proposed rules seemed promising. In light of the general disappointment with the R.A. decision and the proposed rules, on the last day of President Clinton’s term in office, Attorney General Janet Reno vacated and remanded R.A.’s case back to the BIA with an order to stay the decision until the proposed rules were formally adopted.93 Unfortunately, the proposed rules were never adopted and R.A.’s application lingered for another four years.94 86. Ira Mehlman, Clinton’s Subtle, but Historic, Redefinition of U.S. Immigration Policy, FED’N FOR AM. IMMIGR. REFORM (Jan. 10, 2001), http://www.fairus.org/site/PageServer?page name=media_media2468. 87. BILL CLINTON, BETWEEN HOPE AND HISTORY: MEETING AMERICA’S CHALLENGES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY, 133-134 (1996). 88. Asylum and Withholding Definitions, 65 Fed. Reg. 76588, 76588-89 (proposed Dec. 7, 2000) (to be codified at 8 C.R.F. pt. 208). 89. Id. at 76593 (“A particular social group is composed of members who share a common, immutable characteristic, such as sex, color, kinship ties, or past experience, that a member either cannot change or that is so fundamental to the identity or conscience of the member that he or she should not be required to change it.”). 90. Id. 91. Id. at 76594. 92. Id. at 76595 (stating that a case-by-case approach offered the flexibility required to further develop this area of law). 93. In Re R-A-, supra note 60, at 906. 94. Id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 13 19-JAN-12 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 14:13 329 B. The Bush Administration: A Step Back for Battered Women The Clinton Administration’s pro-immigrant position was replaced with President George W. Bush’s “hard-line” approach to immigration reform.95 Just before the INS was permanently transferred into the newly created Department of Homeland Security, Attorney General Ashcroft announced that he planned to issue new regulations that would severely undercut the previously proposed rules by the DOJ.96 Many thought this was a last ditch effort to control the issue on the eve of the DOJ losing jurisdiction on the matter.97 Specifically, the new regulations would directly affect R.A. because the rules threatened to reinstate the BIA decision that denied her asylum.98 The public reacted strongly to this announcement.99 Several House members were concerned that the regulations would reverse the current trend toward granting battered women asylum and wrote Ashcroft urging him not to follow through with his regulations which rejected gender-related violence as a basis for asylum.”100 Additionally, they severely warned Ashcroft that his proposed regulations would “condemn several women and girls to death.”101 Ashcroft failed to pass his proposed rules before the INS move. However, because the BIA remained with the DOJ, Ashcroft still retained jurisdiction.102 In December 2003, Ashcroft ordered briefing on R.A.’s case and many organizations intervened on her behalf. The UNHCR issued an Advisory Opinion urging Ashcroft to adopt the international standards for gender-related persecution claims and to consider its interpretation of the term “particular social group.”103 It reminded Ashcroft that U.S. statutes should be construed consistent with inter95. George W. Bush’s Immigration Policy, ASSOCIATED CONTENT, http://www.associated content.com/article/242279/george_w_bushs_immigration_policy.html (last visited Aug. 28, 2011). 96. Women Asylum Seekers in Jeopardy, LAWYERS COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (Feb. 21, 2003), http://www/lchr.org/media/2003_alerts/0221.htm. 97. Id. 98. Id. 99. Id. 100. Letter from Gregory W. Meeks et al., Congressman, House of Representatives, to John D. Ashcroft, Attorney Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice (Feb. 27, 2003) (on file at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/documents/advocacy/house_2-03.pdf). 101. Id. 102. In re R-A-, 24 I. & N. Dec. 629, 629 (B.I.A. 2008). 103. Letter from Eduardo Arboleda, Deputy Reg’l Representative, United Nations High Comm’r for Refugees, to John D. Ashcroft, Attorney Gen., (Jan. 9, 2004) (on file at http://cgrs. uchastings.edu/documents/legal/unhcr_ra-amicus.pdf). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 330 unknown Seq: 14 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 national obligations.104 It also stated that the term “particular social group”“should be read in an evolutionary manner, open to the diverse and changing nature of groups in various societies and evolving international human rights norms.”105 Furthermore, the UNHCR explicitly provided an interpretation that reconciled the two leading approaches, immutability and the social perception, into a single approach: A particular social group is a group of persons who share a common characteristic other than a risk of being persecuted, or who are perceived as a group by society. The characteristic will often be one which is innate, unchangeable, or which is otherwise fundamental to identity, conscience or the exercise of one’s human rights.106 The UNHCR found that R.A.’s “particular social group can be defined by her sex, marital status, and her position in a society that condones discrimination against women.”107 Additionally, the UNHCR argued that R.A. was in fact persecuted on account of her group. According to UNHCR, group membership “must be a relevant contributing factor, though it need not be shown to be the sole, or dominant cause.”108 The UNHCR also provided that in situations where the persecution was at the hands of a non-state actor or for reasons unrelated to a recognized ground, but where there existed an “inability or unwillingness of the State to offer protection,” the nexus requirement was met.109 This alternative analysis is sometimes referred to as a “bifurcated nexus.”110 Using this approach, UNHCR concluded that although R.A.’s husband may have been abusing her in part for personal reasons, there was still enough evidence that he was also abusing her because she was his property through marriage.111 As UNHCR explained, in Guatemala, 104. Id. (citing Murray v. Charming Betsy, 6 U.S. 64, 118, (1804)) (“[A]n act of Congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations if any other possible construction remains.”); see I.N.S. v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421, 432-33 (1987) (“[The US Supreme Court found] abundant evidence of an intent to conform the definition of “refugee” and our asylum law to the United Nation’s Protocol to which the United States has been bound since 1968.”). 105. See Letter from Eduardo Arboleda to John D. Ashcroft, supra note 103, at 7. 106. Id. at 8. 107. Id. at 9 (“Women are expected to accept their ‘fate’ without protest and without involving the authorities at all. This is another element identifying her as part of a particular social group.”). 108. Id. at 10. 109. Id. 110. Letter from Eduardo Arboleda to John D. Ashcroft, supra note 103, at 10-11 n. 50 (“There is ample evidence that [Guatemala] discriminates against women and tolerates male dominance and abuse of married women by their husbands.”). 111. Id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 15 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 331 it was understood that R.A.’s husband would not likely face prosecution and therefore, “[she] should be recognized as a refugee” by the United States.112 Others also advocated on behalf of R.A. . The DHS submitted a supplemental brief (2004 Brief). It recommended that the DOJ grant victims of domestic abuse asylum under such extreme circumstances as R.A.’s.113 Additionally, the Senate wrote Ashcroft a letter and urged him to issue regulations in line with those promulgated in the 2004 Brief.114 The Senate defused fears of mass asylum applications by pointing out that other countries already recognized gender-based asylum claims and that in those countries it did not lead to a “proliferation of such claims.”115 However, Ashcroft resigned without ever reaching a decision in R.A.’s asylum claim.116 Shortly after Ashcroft’s resignation, L.R., another foreign victim of domestic abuse, arrived in the United States and sought asylum protection. L.R. endured years of torture at the hands of her common-law husband in Mexico.117 She was only a teenager when he, fourteen years her senior, began to sexually abuse her.118 He used his position as her physical education coach combined with his family’s wealth and influence “to dominate and scare her.”119 He repeatedly and violently raped her for years, even while she was pregnant.120 On one occasion, while pregnant, L.R. tried to escape and was caught by her husband who beat her and set the bed on fire while she was asleep.121 When L.R. sought help from the authorities, she was told that her situation was a private and domestic matter regardless of visi- 112. Id. at 10, 13. 113. Rachel L. Swarns, Ashcroft Weighs Granting Political Asylum to Abused Women, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 11, 2004, at A1. 114. Letter from Hillary Rodham Clinton et al., U.S. Senator, to John D. Ashcroft, Attorney Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice (June. 16, 2004) (on file at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/documents/advocacy/senate_6-04.pdf). 115. Id. 116. John David Ashcroft, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, http://www.justice.gov/ag/aghistpage. php?id=78 (last visited Aug. 28, 2011). 117. See Amended Declaration of L.R. in Support of Application for Asylum at 7 (Dec. 30, 2005) [hereinafter Declaration of L.R.] available at http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/ us/20090716-asylum-support.pdf. 118. Id. at 3. 119. Id. 120. See id. at 7-8. 121. Id. at 7. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 332 unknown Seq: 16 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 ble injuries.122 On another occasion, a judge told her that he would assist her, but only if she “had sex with him” first.123 L.R. fled from her husband to the United States.124 She was automatically placed in removal proceedings because she applied for asylum seven months past the one-year window.125 On October 15, 2007, an immigration judge denied L.R.’s application for removal because she articulated her particular social group as “Mexican women in an abusive relationship who are unable to leave.”126 The immigration judge found this formulation impermissibly circular and “centrally defined by the existence of the abuse [she] fear[ed].”127 Meanwhile, then Attorney General Mukasey remanded R.A.’s case back to the BIA for reconsideration.128 C. A Renewed Promise: The Obama Administration With a new administration in office, the possibility of asylum for battered women appears promising. First, the DHS intervened in L.R.’s case by once again submitting a supplemental brief (2009 Brief) supporting granting her asylum.129 Many saw this as a direct response by the Obama Administration against the Bush Administation’s antiasylum policy for battered women.130 The 2009 Brief explained that in order to show membership in a particular social group, an applicant must demonstrate that its members “share a common immutable or fundamental trait, [that is] socially distinct or ‘visible,’ . . . and defined with sufficient particularity to allow reliable determinations about who comes within the group[s] definition.”131 The DHS recommended that the BIA remand L.R.’s case back to an immigration judge for further investigation and to take into account “intervening case law” and the alternative formulations for meeting the require122. Declaration of L.R., supra note 117, at 8. 123. Id. at 13. 124. Id. at 24. 125. Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 [IIRIRA], Pub. L. No. 104-208, § 601, 110 Stat. 3009-546 [hereinafter IIRIRA] (codified as amended at 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42) (Supp. II 1996) (enacted as Division C of the Departments of Commerce, Justice, State, and the Judiciary Appropriations Act for 1997). 126. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 2, 5. 127. Id. at 6. 128. In re R-A-, 24 I. & N. Dec. 629, 632 (B.I.A. 2008). 129. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 16. 130. Julia Preston, New Policy Permits Asylum for Battered Women, N.Y. TIMES, July 15, 2009, at A1. 131. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 16. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 17 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 333 ments it suggested in its 2009 Brief.132 Under this framework, the DHS stated that L.R.’s proposed group is either “[M]exican women in domestic relationships who are unable to leave” or “[Mexican] women who are viewed as property by virtue of their positions within a domestic relationship.”133 The DHS also reiterated that “this does not mean that every victim of domestic violence would be eligible for asylum” and that all other elements of an asylum claim must still be met.134 In the meantime, progress was made in R.A.’s case. On October 28, 2009, the DHS wrote a single-paragraph letter to the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). In that letter, the DHS explained that after it had reviewed additional evidence provided by R.A., it found that she was “eligible for asylum and merits . . . asylum as a matter of discretion.”135 The EOIR remanded R.A.’s case back to an immigration judge for determination. Finally, on December 10, 2009, after a fourteen year-long legal battle, R.A. was granted asylum.136 The immigration judge’s decision simply read, “[i]nasmuch as there is no binding authority on the legal issues raised in this case, I conclude that I can conscientiously accept what is essentially the agreement of the parties [to grant asylum].”137 Congress also took some steps in the right direction. The House of Representatives introduced a bill that would eliminate a rule that automatically denied affirmative asylum claims if they were filed a year or longer after arriving in the United States.”138 L.R. and 35,000 other applicants were denied asylum under this same rule.139 The House of Representatives expressed concerns that “[v]ictims of torture and gender-related persecution who flee to the United States [were] being sent back because of this arbitrary one-year bar.”140 The 132. See id. at 21 (Explaining that the BIA could not grant L.R. asylum using the DHS formulations because they were not offered at the initial hearing, remand is appropriate when new claims are involved and further development of the case is necessary). 133. Id. at 14. 134. Id. at 12. 135. Brief for Respondent, In Matter of Rodi Alavarado-Pena, (BIA 2009), No. A073 753 922, available at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/about/contact.php. 136. Documents and Information on Rody Alvarado’s Claim for Asylum in the U.S., CENTER FOR GENDER & REFUGEE STUDIES, available at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/campaigns/alvarado. php (last visited August 27, 2011). 137. Id. 138. Restoring Protection to Victims of Persecution Act, H.R. 4800, 111th Cong. (2010). 139. Press Release, Congressman Jim Moran, Moran, Stark& Watson Demand Safe Haven for Refugees (Mar. 10, 2010) (on file at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/pdfs/Moran%20PRESS%20 RELEASE.pdf). 140. Id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 334 unknown Seq: 18 19-JAN-12 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 14:13 [Vol. 18 Senate also followed and introduced its own comprehensive immigration reform bill that did away with the one-year bar rule and the “visibility” requirement from the DHS 2009 Brief.141 On August 4, 2010, all this progress culminated with an immigration judge’s decision to grant L.R. asylum.142 IV. THE STATUS OF ASYLUM RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BATTERED WOMEN AND In light of the uncertainty that remains in asylum law for victims of domestic violence, the Obama Administration needs to make this area of law a priority. First, this Administration must work with Congress to formally amend The Refugee Act of 1980. Second, the Administration needs to put pressure on its agency heads to issue joint regulations that formally recognize battered women as a “particular social group” for purposes of refugee protection. As this Comment demonstrates, the United States’ position on asylum for victims of domestic violence greatly depends on who is in office. During the Clinton Administration, and for the first time in the United States’ history, proposed regulations would have recognized battered women as members of a “particular social group.” At the other extreme, the Bush Administration not only failed to adopt those regulations, but rather threatened to issue its own set of regulations that would have severely undercut the progress made at that point for battered women. Currently, under the Obama Administration, once again there is talk of proposing new regulations that will formally recognize that under certain circumstances, battered women qualify for asylum. The major deficiency at this point, however, is that no formal regulations have been adopted by either agency involved in asylum adjudication. A. A Lesson from the United State’s response to China’s “One Child Policy” This is not the first time the United States has been faced with advancing legislation to address the inconsistent and inefficient adjudication of asylum claims. In 1979, the Chinese government implemented their “One Child Policy.”143 This zero-tolerance policy 141. Refugee Protection Act of 2010, S. 3113, 111th Cong. (2010). 142. Matter of L.R., CENTER FOR GENDER & REFUGEE STUDIES, available at http://cgrs. uchastings.edu/campaigns/Matter%20of%20LR.php (last visited Aug. 27, 2011). 143. Charles E. Schulman, The Grant of Asylum to Chinese Citizens Who Oppose China’s One-Child Policy: A Policy of Persecution or Population Control?, 16 B.C. THIRD WORLD L.J., 313, 316-17 (1996). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 19 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 335 imposed penalties that “range[d] from physical force and imprisonment to mere persuasion and economic sanctions,” such as “loss of employment or demotion, fines, and denial of human services” for families that gave birth to more than one child.144 More “extreme punishments, namely forced abortion or sterilization,” were also used.145 Fearing the potential of such penalties, many individuals fled China.146 Like victims of domestic abuse, once these individuals arrived in the United States, they were faced with inconsistent rulings on whether claims based on China’s new policy met the requirements for persecution based on political opinion.”147 This led then-Attorney General Edwin Meese to issue a memo that directed “all asylum officers to give ‘careful consideration’ to Chinese applicants expressing a fear of persecution based on China’s policy.”148 The BIA, however, promptly held that the Meese memo was not binding on the BIA or immigration judges in Matter of Chang.149 As a direct response to Chang, President George H.W. Bush issued an executive order “granting asylum to refugees from the One Child Policy.”150 Unfortunately, when the INS issued its final asylum regulations, this language was omitted.151 Subsequently, the BIA refused to recognize that Chang was overruled.152 Other remedial efforts were made, such as a memo in 1991 from then-INS General Counsel, Grover Joseph Rees, stating that these applicants “could establish eligibility for asylum.”153 Again, this memo was not binding on the BIA or immigration judges.”154 The following four years produced a number of ambiguous decisions.155 Circuit courts quickly overruled district courts that granted asylum to refugees who fled China because of the One Child Policy.156 For example, in Guo Chun Di v. Carroll, a district court granted the applicant asy144. Id. at 317. 145. Id. 146. Id. at 319. 147. Id. at 320. 148. Kimberly Sicard, Section 601 of IIRIRA: A Long Road to a Resolution of United States Asylum Policy Regarding Coercive Methods of Population Control, 14 GEO. IMMIGR. L.J. 927, 933 (2000). 149. Chang, No. A-27202715, 1989 BIA LEXIS 13, at *13 (BIA May 12, 1989). 150. Sicard, supra note 148, at 934. 151. Id. 152. Id. 153. Id. 154. Id. 155. See id. at 934-936. 156. Sicard, supra note 148, at 934-36. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 336 unknown Seq: 20 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 lum finding that he met the requirement for persecution on account of his political opinion.157 The Fourth Circuit reversed the decision and stated that Chang was still controlling precedent and, therefore, this applicant was not eligible for asylum because he opposed China’s policy.158 This same “yes-then-no” adjudication pattern played out in the Second Circuit as well.159 Congress’ appropriate response to this inefficient application process was the Illegal Immigration and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, specifically Section 601(a) (IIRIRA).160 IIRIRA enlarged the definition of refugee with the following language: For purposes of determination under this Act, a person who has been forced to abort a pregnancy or to undergo involuntary sterilization, or who has been persecuted for failure or refusal to undergo such a procedure or for other resistance to a coercive population control program, shall be deemed to have been persecuted on account of political opinion, and a person who has a well founded fear that he or she will be forced to undergo such a procedure or subject to persecution for such failure, refusal, or resistance shall be deemed to have a well founded fear of persecution on account of political opinion.161 While IIRIRA retained the same “evidentiary burden” that all asylum-seekers must meet, meaning that all other elements still needed to be satisfied,162 it helped asylum-seekers who had been the victim of coercive family planning measures or who reasonably feared that he or she would be subjected to them if they returned to their country presumptively satisfy the element of a “well founded fear of persecution.”163 157. Guo Chun Di v. Carroll, 842 F. Supp. 858, 874 (E.D. Va. 1994) rev’d sub nom. Guo Chun Di v. Moscato, 66 F.3d 315 (4th Cir. 1995). 158. Sicard, supra note 148, at 935. 159. Id. at 936 (for example, the Second Circuit). 160. Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 §601(a) (enacted as Division C of the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, and the Judiciary Appropriations Act of 1997), 8 U.S.C. §1101 (2006). 161. Kyle R. Rabkin, The Zero-Child Policy: How the Board of Immigration Appeals Discriminates Against Unmarried Asylum-Seekers Fleeing Coercive Family Planning Measures, 101 NW. U. L. REV. 965, 974 (2007). 162. Id. at 975. 163. Id. at 974. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 21 19-JAN-12 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 14:13 337 B. The Obama Administration Should Amend The Refugee Act As the events that led to IIRIRA indicate, inconsistent rules and “an ad hoc, politicized regime” cannot govern asylum law.164 In general, asylum law produces the least consistent results when it comes to adjudication.165 Discrepancies exist even when there is no change in the law and their existence is prevalent throughout the process, from immigration judges up to the Courts of Appeal.166 The problem is further compounded because asylum law is administered by two separate agencies: the DHS whose policy recognizes and grants battered women asylum,167 and the BIA, which applies inconsistent interpretations of the term “particular social group” and does not fully recognize gender as an “immutable characteristic.”168 A clear, legislative act is the only remedy to ensure that women facing extreme cases of domestic abuse in foreign countries receive fair adjudication and protection in the United States. Like the various memos issued prior to IIRIRA’s enactment, neither In re R.A. nor In re L.R. are binding. Both cases provide short decisions that do not include any analysis. In addition, neither of the decisions provided guidelines nor legal tests for future cases to apply, nor do they give any indication if the formulations proposed satisfy the DOJ’s interpretation of “membership in a particular social group.” In other words, the only thing the decisions accomplished is granting these two particular applicants asylum. This is of little help to other battered women who seek asylum and especially troubling in light of the clear opposition within the DOJ to recognize genderbased asylum.169 The DHS’s 2009 Supplemental Brief is slightly more helpful for future applicants who seek protection because of domestic abuse. The Brief states that it “represents the Department’s current position” and that it was written with the intent to create “better guidance [for] both adjudicators and litigants.”170 This means that asylum officers must decide asylum claims consistent with the guidelines announced in this 164. See Alex Kotlowitz, Asylum for the Worlds Battered Women, N.Y. TIMES, Feb. 11, 2007, at Sec. 6. 165. Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Andrew I. Schoenholtz & Philip G. Schrag, Refugee Roulette: Disparities in Asylum Adjudication, 60 STAN. L. REV. 295, 302 (2007). 166. Id. 167. See 2009 Brief, supra note 31. 168. See Matter of Acosta, supra note 48. 169. Press Release, FEMINIST.COM, U.S. Asylum for Gender Violence Victims Stalled (March 27, 2003) (on file with author at http://www.feminist.com/news/news176.html). 170. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 4-5. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 338 unknown Seq: 22 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 brief. However, this does not necessarily help women who fail to apply by the one-year deadline, even by a day. These women are still automatically denied asylum and placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge.171 In contrast to DHS asylum officers, DOJ immigration judges are not required to follow these guidelines, which are merely persuasive authority. As demonstrated, this can lead to inconsistent results. Therefore, President Obama should to make this area of law a priority. During his victory speech, President Obama reminded the nation that “America’s beacon still burns bright” and that our “true strength . . . comes . . . from the enduring power of our ideals: democracy, liberty, opportunity and unyielding hope.”172 Advocates expected his Administration to be a significant contrast to its predecessor and pick up where the Clinton Administration left off.173 Yet, despite the victories for R.A. and L.R., asylum law is no clearer today than it was under President Bush’s leadership. The appropriate response is to enact new legislation similar to IRIRA that would amend the Refugee Act by recognizing that, under certain circumstances, battered women are persecuted on account of their membership in a particular social group. The language should mirror the language used in IIRIRA. For example, the legislation could read as follows: “A refugee, for purposes of the Refugee Act, includes any person who has been subjected to physical abuse at the hands of their partner, in a country where women are viewed as property and/or domestic violence is viewed as a private matter and the individual is unable to leave or receive assistance from his or her government, shall be deemed to have been persecuted on account of their membership in a particular social group.” As with IIRIRA, the amended language would create a presumption of persecution on account of membership in a protected category. While the burden on the applicant would remain the same, it would create a clear starting point for adjudicators and applicants alike that would lead to more consistent results. 171. IIRIRA, supra note 125 (creating among other things, an arbitrary filing deadline that bars asylum if the application was not filed within one-year of entry unless the applicant meets one of two exceptions.) 172. Speech, supra note 1. 173. See Erica Hagen, Elections Hold Key to Asylum for Abused Women, WOMEN’S ENEWS, (Nov. 4, 2008), http://www.womensenews.org/story/campaign-trail/081104/elections-hold-keyasylum-abused-women. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 23 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 339 C. The Obama Administration Should Promulgate Joint Regulations Until the Refugee Act can be amended, the DHS and the DOJ should jointly issue regulations that clearly instruct all adjudicating bodies on the proper analysis for an asylum claim based on domestic violence. Almost eleven years have passed since the first set of proposed regulations was announced.174 During this period, the DOJ, through its BIA and immigration judges, has issued numerous inconsistent decisions.175 The BIA in particular has required that applicants demonstrate that their group be “socially visible” in order to meet the element of membership in a particular social group.176 This is a requirement that the court in Acosta did not intend.177 The nexus requirement between persecution and membership in a particular social group has also become difficult to interpret and especially disadvantageous to asylum seekers who are victims of domestic abuse.178 The Obama Administration must exercise its executive powers and put pressure on both the DHS and the DOJ to issue joint regulations that revert back to Acosta’s requirements and accurately reflect the UNHCR guidelines, both of which recognize that gender is an immutable characteristic that satisfies the membership in a particular social group requirement.179 First, the regulations should drop the “visibility” requirement. This requirement was set forth in the DHS 2009 Brief with little guidance on how to apply it.180 Additionally, courts that have applied this requirement have done so inconsistently; some apply it in its literal sense, that the individual members be identifiable as group members to complete strangers; while others require that the group be recognized as a group by society.181 It is also at times wrongly joined 174. Asylum and Withholding Definitions, 65 Fed. Reg. 76588-01 (proposed Dec. 7, 2000). 175. See How to Repair the U.S. Asylum System: Blueprint for the Next Administration, HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST, 11 (Dec. 2008), http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/pdf/081204-ASY-asylum-blueprint.pdf [hereinafter Blueprint]. 176. See A-M-E & J-G-U-, 24 I. & N. Dec. 69, 74 (BIA 2007); S-E-G-, 24 I. & N. Dec. 579, 582 (BIA 2008) (both cases showing analysis using particular social group framework as applied to non gender based claims). 177. Matter of Acosta, supra note 15, at 233. 178. Barbara R. Barreno, In Search of Guidance: An Examination of Past, Present, and Future Adjudications of Domestic Violence Asylum Claims, 64 VAND. L. REV. 225, 256 (2011). 179. Matter of Acosta, supra note 15, at 233; GUIDELINES, supra note 46, at 3. 180. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 8. 181. Statement for the Hearing Record on “Renewing America’s Commitment to the Refugee Convention: The Refugee Protection Act of 2010,” CENTER FOR GENDER & REFUGEE STUDIES, (May 19, 2010) [hereinafter Statement] available at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/pdfs/CGRS%20 Statement%20SJC%20Hearing%20on%20RPA%205-26-10.pdf. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 340 unknown Seq: 24 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 to the nexus requirement.182 The visibility requirement has served to deny asylum to many battered women.183 Yet, one Court of Appeals Judge described this requirement as counterintuitive and “simply making ‘no sense’ because members of a group targeted for persecution take pains to avoid being socially visible.”184 Second, the regulations must clearly establish that an applicant can prove that they are persecuted on account of their membership in a particular social group using circumstantial evidence. This is because persecutors rarely articulate why they abuse their victim, in fact, the Supreme Court allows an applicant to demonstrate the persecutor’s motive by “some evidence, direct or circumstantial.185 Moreover, the new INS regulations proposed by President Clinton in 2000 and the DHS Briefs also allow applicants to submit circumstantial evidence.186 Yet, despite this general agreement, many asylum claims have been denied for failing to produce direct evidence that fulfills the nexus requirement.187 As both R.A.’s and L.R.’s cases illustrate, it is particularly difficult for battered women to establish nexus when the aggressor is a non-state actor. Allowing circumstantial evidence to prove the requirement resolves a practical reality without sacrificing the legitimacy of a claim. V. SILENCING FAILS THE CRITICS: WHY THE FLOODGATES ARGUMENT Critics argue that granting battered women asylum will open up the floodgates, thereby overwhelming the court system. They point to alarming statistics for battered women in countries like Ethiopia, where it is reported “that as many as 6 of every 10 women [are] beaten or sexually assaulted by their husbands or partners,” suggesting that all of these women would flood U.S. borders.188 This floodgate concern is meritless because international and domestic statistics say otherwise. First, countries that recognize gender-based claims did not experience a drastic increase in applications.189 Second, 182. Id. 183. Id. 184. Id. (citing cases such as homosexuals who disguise themselves as heterosexuals or women that have not yet undergone female genital mutilation). 185. I.N.S. v. Elias-Zacarias, 502 U.S. 478, 483 (1992). 186. Barreno, supra note 178 at 239. 187. Statement, supra note 181. 188. Kotlowitz, supra note 164. 189. See generally Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada: An Overview, IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEE BOARD OF CANADA [hereinafter An Overview], http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/Eng/ brdcom/publications/oveape/Documents/overview_e.pdf. (last visited Dec. 15, 2010). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 25 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 341 there are sufficient safeguards within the United States’ asylum application process.190 Third, by reinforcing the United States’ commitment to protecting battered women, recognized as qualified refugees by the United Nations, a clear message is sent to those countries that have lax domestic violence laws that they need to solve their domestic violence problems within their borders if they want to avoid receiving negative international publicity. Thus, there is insufficient evidence to support the conclusion that gender-based applications for asylum would be so overwhelming that as an entire group they ought to be denied protection. A. Statistics Say Otherwise Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, among others, recognize gender-based asylum and have not experienced an influx in applications.191 In 1993, Canada, whose asylum process is similar to that of the United States,192 began recognizing marital status and gender for purposes of asylum.193 In 1995, however, the total number of gender-based asylum applications was 350 out of more than 31,000 asylum applications total.194 By 1999, the total number of gender-based asylum applications dropped to only 175.195 Clearly, gender-based claims have not led to a rush of applicants in Canada. Here, in the United States, the total number of asylum applications in general has consistently declined over the years. In 2003, the DHS granted a total of 28,737 asylum applications.196 Once the 2004 Brief was issued, battered women were recognized by the DHS as members of a particular social group and received asylum.197 Since then, the number of applicants who receive asylum has decreased steadily.198 The total number of applicants granted asylum in 2009 190. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 12. 191. Brief for Respondent at 11 n.12, In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. 906 (B.I.A. 2001) (No. A 73 753 922), available at http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/documents/legal/ra_brief_final.pdf. 192. See generally Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada: An Overview, IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEE BOARD OF CANADA (Mar. 2006), 3-28, http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/Eng/brdcom/ publications/oveape/Documents/overview_e.pdf [hereinafter Overview]. 193. Id. at 16. 194. Kristin E. Kandt, Comment, United States Asylum Law: Recognizing Persecution Based on Gender Using Canada as a Comparison, 9 GEO. IMMIGR. L.J. 137, 165 (1995). 195. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 13 n.10 (these are latest published statistics). 196. Office of Immigration Statistics, 2009 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, U.S. DEP’T OF HOMELAND SECURITY (Aug. 2010), 43 http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/yearbook/ 2009/ois_yb_2009.pdf [hereinafter Statistics]. 197. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 13 n.10. 198. See Statistics, supra note 196, at 43 (2004 - 27,316, 2005 - 25,221, 2006 - 26,272). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 342 unknown Seq: 26 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 was only 22,119, the lowest number since 2000.199 These numbers do not suggest that asylum claims are flooding in; instead, they seem to be drying up. This seems to be equally true for gender-based applications in general. One possible explanation is that most women who would qualify for asylum do not have the resources to flee their country.200 Even if they did, they are unlikely to obtain the legal assistance or agency support that both R.A. and L.R. enjoyed.201 Likewise, the United States has not seen a flood of applications ensue since it recognized other types of gender-based asylum claims, such as female genital mutilation victims. Critics argued that there would be a drastic increase in applications because “millions of women are subject to female genital mutilation a year.”202 Instead, evidence indicates that the number of women seeking asylum for female genital mutilation remains low.203 One possible explanation is that countries with the highest rates of female genital mutilation are not the same countries with the highest number of immigrants seeking asylum.204 This is also true for domestic violence. Of the ten countries with the highest asylum applicants, only three of them are considered “one of the worst countries for women” based on statistical data such as societal tolerance for domestic abuse.205 Looking at the number of female genital mutilation applications, it is not unreasonable to assume that we can expect the same results if protection were granted to victims of domestic violence. B. The Burden Remains High Proponents of the floodgate argument ignore the fact that recognizing gender-based claims for purposes of establishing one of the protected groups is but a single element of an entire asylum claim. This weakens the floodgates theory because not every person who 199. Id. at 43. 200. See Ashley Michelle Papon, Obama Administration Extends Asylum for Domestic Violence Victims, GLOBAL SHIFT (Aug. 16, 2010), http://www.globalshift.org/2010/08/16/obama-administration-extends-asylum-for-domestic-violence-victims/. 201. Id. 202. Chris McGreal, Obama Moves to Grant Political Asylum to Women Who Suffer Domestic Abuse, GUARDIAN.CO.UK (July, 24, 2009, 17:17 BST), http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/ jul/24/obama-women-abuse-political-asylum-us. 203. See Zainab Zakari, FGM Asylum Cases Forge New Legal Standing, WOMEN’S ENEWS (Nov. 25, 2008), http://www.womensenews.org/story/genital-mutilation/081125/fgm-asylumcases-forge-new-legal-standing. 204. Id. 205. See Olivia Ward, Ten Worst Countries for Women, thestar.com (Mar. 8, 2008), http:// www.thestar.com/News/World/article/326354 (those countries are Iraq, Nepal, and Guatemala). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 27 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 343 files an application will be granted asylum.206 While some facts may be used to prove more than one element,207 like the results after IIRIRA, formally recognizing battered women as members of a particular social group would only create a presumption for one element and would not make it easier in general to prove all other elements.208 In fact, meeting all the elements for an asylum claim can be particularly difficult for a victim of domestic violence. The burden has been described as a “heavy one.”209 First, she must demonstrate that the abuse is severe enough that it rises to a level of persecution.210 Second, the past persecution must cause her to fear harm and this fear must be well-founded.211 Third, the applicant must provide documented evidence that relocating within her home country is not a reasonable option.212 Finally, because the aggressor is not the country itself, she must show that the country is unwilling or unable to protect her.213 These last two elements are the toughest to meet because they are “designed to narrow the class” to only include applicants who come from countries where domestic abuse is woven into the country’s fabric.214 In other words, domestic violence is so pervasive because the country either has no laws in place to prevent it or if the country does, it must refuse to enforce them.215 C. Sending a Clear Message Recognizing victims of domestic violence as a class eligible for asylum promotes domestic abuse awareness both internationally and domestically. There are critics who believe that granting asylum to domestic abuse victims reduces the pressure on countries with lax domestic violence laws because they know that victims within their bor206. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 12. 207. Id. at 21. 208. See Rabkin, supra note 161, at 975 (as one member of Congress put it during the debates for passage of IIRIRA, “[t]he solution to credibility problems is careful case-by-case adjudication, not wholesale denial.”). 209. 2009 Brief, supra note 31, at 12 (quoting Fisher v. INS, 79 F.3d 955, 961 (9th Cir. 1996) (en banc)). 210. Id. 211. Id. 212. Id. 213. Id. at 12-13. (DHS also points out that many of these women would not have the available resources to leave in the first place). 214. See David Ma, The Obama Administration’s Policy Change Grants Asylum to Battered Women: Female Genital Mutilation Opens the Door for All Victims of Domestic Violence, SELECTED WORKS, http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=david_ma (last visited Sept. 1, 2011). 215. See id. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 344 unknown Seq: 28 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 ders can receive protection elsewhere, thereby creating little incentive for those countries to address and rectify the condition at home.216 A similar theory suggests that this allows the battered victim to flee from the problem. These critics argue that it provides no incentives to seek reform in her home country.217 Both of these arguments are flawed. It is doubtful that any country wants the kind of negative publicity that would follow if women were fleeing the country to seek asylum in the United States. Such publicity, however, may actually help force those countries towards reform. In fact, since R.A.’s case made headlines, “Guatemala is making efforts to reduce spousal abuse through ‘nationwide educational programs.’”218 The country has also passed a law that judges “may issue injunctions against abusive spouses, which police are responsible with enforcing.”219 Additionally, it is simply unrealistic to expect a woman who is unable to receive assistance from the government with her own matter, to expect an entire group of similarly situated women in her same country to receive help. Further, recognizing that women deserve refugee protection from domestic abuse reinforces the United States’ commitment to curing human rights violations. Critics argue that granting battered women asylum will undermine efforts against domestic violence here in the United States.220 The reality is that the United States is in a much better position to provide these women assistance compared to other countries. An argument premised on the idea that the United States should not offer protection to foreign victim of domestic abuse because they are too numerous is simply callous and demonstrates “an appalling indifference to human suffering.”221 The United State’s failure to take adequate steps to protect these women could be inter216. Cf. Daniel F. E. Smith, Refusing to Expand Asylum Law: An Appropriate Response by the Fourth Circuit in Niang v. Gonzales, 87 N.C. L. REV. 1279, 1297 (2009) (similar argument made but in the context of female genital mutilation). 217. See id. 218. Jon Feere, Open Border Asylum: Newfound Category of ‘Spousal Abuse Asylum’ Raises More Questions Than It Answers, CENTER FOR IMMIGRATION STUDIES, 12-13 (July 2010), http:// www.cis.org/articles/2010/alvarado.pdf (U.S. State Department’s advisory opinion on R.A.’s case). 219. Id. at 13. 220. Obama Administration Ignores Law, Advocates Asylum for Victims of Foreign Domestic Violence, FEDERATION FOR AMERICAN IMMIGRATION REFORM (July 20, 2009), available at http:/ /www.fairus.org/site/News2/1901162313?page=NewsArticle&id=20995&security=1601&news_iv _ctrl=1012. (It is unfair to the American people to ask them to embrace a policy that attempts to right every wrong and rectify every misfortune, wherever it occurs, no matter who is responsible by bringing the victims into the United States for permanent residence and giving them instant access to welfare programs, housing assistance, and other taxpayer-supported public assistance programs that are available only to the neediest Americans.). 221. Papon, supra note 200. \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 2011] unknown Seq: 29 VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 19-JAN-12 14:13 345 preted as supporting the practices of these countries, or at the least, as passive in the fight against domestic abuse. Surely this is not the message the Obama Administration wants to send to women in the United States. As the foregoing responses indicate, the fears held by the floodgates critics are clearly unfounded. Recognizing battered women under asylum law will not only protect the dignity of women suffering from domestic abuse, but may also help to spur their home countries to action so that future women will not have to flee their home countries leaving everything behind in order to escape the abuse. VI. CONCLUSION Post World War II, the United States was the leading supporter in “the efforts to create an international refugee protection regime.”222 Through the Refugee Act, it “has welcomed the refugees from some of the world’s most desperate refugee [crises].”223 Today the United States still prides itself “as a beacon of hope and safety for the persecuted around the world.”224 However, for individuals who flee persecution based on gender, this is not the case. For almost twenty-one years now, the United States has consistently denied foreign victims of domestic abuse shelter within its borders. It has continued to ignore international urging and its commitment to the Convention. Some administrations, such as Clinton’s Administration, have made noble attempts to rectify the problem. Those attempts unfortunately fell short of creating any long-lasting rules. This left the process open to attack by other administrations, like the Bush Administration, that threatened to undo all progress made up until that point. Now we have a new administration that talks about once again making positive changes for battered women who seek asylum in the United States. But unless these changes are formally implemented through legislation or agency regulations, this administration’s efforts are doomed to suffer the same fate as the proposed regulations of 2000. As the law stands today, battered women who seek asylum will continue to face an uncertain future. This Administration should feel confident that there would not be a flood of new asylum applications. The United States has two 222. Renewing U.S. Commitment to Refugee Protection: Recommendations for Reform on the 30th Anniversary of the Refugee Act, HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST, 6 (Mar. 2010), http://www.human rightsfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/30th-AnnRep-3-12-10.pdf. 223. Id. at 7. 224. See Blueprint, supra note 175, at 1 (statement of President-Elect Barack Obama). \\jciprod01\productn\S\SWT\18-1\SWT127.txt 346 unknown Seq: 30 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 19-JAN-12 14:13 [Vol. 18 other events in its recent history that suggest this: China’s “One Child Policy” and female genital mutilation. Further, as the UNHCR points out, “the fact that large numbers of persons risk persecution cannot be a ground for refusing to extend international protection where it is otherwise appropriate.”225 By formally recognizing that battered women do qualify for asylum, this government would put an end to the inefficiency that has plagued asylum law for several years. Most importantly, it reinforces the message that the United States does not condone this type of behavior, either abroad or within its borders. 225. GUIDELINES, supra note 46, at 2.