The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S. Business Cycle First

advertisement

First motivation: spending 07-09

The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in

the U.S. Business Cycle

Alisdair McKay and Ricardo Reis

�

In the 1930s, purchases were 78% of spending. In the

2000s, they were 25%-52%.

�

2007-09 saw the largest increase in government spending /

GDP since the Korean war. But 75% was an increase in

transfers, and only 25% were purchases. (Oh, Reis, 2011)

�

Of the $494bn spent 2007-09 in the ARRA, only $37bn

were spent in purchases (CBO, 2012)

�

The United States is not special in both of these facts.

(Oh, Reis, 2011)

�

The times of Keynes are long gone: the money is in

∆Y = (∂Y /∂T ) ∆T now, not in ∆Y = (∂Y /∂G) ∆G

anymore.

Boston University and Columbia University

June 18th

Sciences Po

Second motivation: automatic stabilizers

�

Big: CBO (2011) estimates that automatic stabilizers in

2012 will account for $343bn, or 35% of the federal deficit.

�

Less controversial: Auerbach (2009), Feldstein (2009):

disagree on countercyclical fiscal policy, agree that

automatic stabilizers are valuable.

�

Policy: IMF (2009) recommendation for every country.

�

Virtue of rule: Solow (2004): “The advantage of automatic

stabilization is precisely that it is automatic. It is not

vulnerable to the perversities that arise when a

discretionary “stimulus package” (or “cooling-off package”)

is up for grabs in a democratic government.”

�

Ignorance: Blanchard (2006): “...very little work has been

done on automatic stabilization in the last 20 years.”

What this paper does

�

The question: By how much do the automatic stabilizers in

the U.S. tax-and-transfer system lower the volatility of

aggregate activity?

�

The approach: Quantitative business-cycle model, with a

role for aggregate demand, incentives, and redistribution.

�

Existing literature:

1. Single stabilizer, single mechanism (Christiano, 1984, Gali, 1994,

Andres Domnech, 2006, Dromel, Pintus, 2007);

2. Discretionary policy changes (Oh Reis, 2011, Huntley

Michelangeli, 2011, Kaplan Violante, 2012);

3. Public finance perspective (Auerbach Feenberg, 2000, Auerbach,

2009, Dolls, Fuest Peichl, 2011);

4. Steady state effect (Floden, 2001, Alonso-Ortiz Rogerson, 2010,

Horvath Nolan, 2011).

Outline for today

1. Introduction

2. What are the automatic stabilizers and what is their role?

3. A model

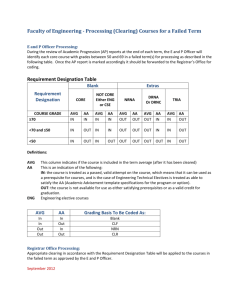

2. The automatic stabilizers: what they are

and what is their role

6$(106-215%!10!$;1.$%2?!-0!23$!0$%0121;127!5=!2->$0!25!1%:54$!./'1%(!23$!<$'15.!*++@AB!C-0!65C$'!

#$$%&$'(!)*+++,!-%.!/01%(!23$!0-4$!4$235.565(78*!!93$!:/4/6-21;$!14<-:2!5=!:3-%($0!1%!2->!

4. First result: neutrality

23-%!-2!-%7!214$!01%:$!23$!DEF+08!!G0214-2$0!=5'!*++H!-%.!23$'$-=2$'!.5!035C!-%!1%:'$-0$.!

5. Second result: complete markets

'$0<5%01;$%$00?!&/2!23$0$!$0214-2$0!'$=6$:2!2->!6-C!-0!1%!$==$:2!41.C-7!23'5/(3!*++H!-%.!

23$'$=5'$!-!02'5%($'!&12$!='54!23$!I62$'%-21;$!J1%14/4!9->!)IJ9,?!23$!$%:'5-:34$%2!5=!C31:3!

6. Third result: redistribution

7. Conclusion

3-0!&$$%!:5%21%/-667!.$6-7$.!&7!-%%/-6!6$(106-215%!1%!'$:$%2!7$-'0?!-%.!$;$%2/-6!'$<$-6!5=!

$00$%21-667!-66!5=!23$!K/03!2->!:/20!$%-:2$.!1%!*++D!-%.!*++@8!!L%$!41(32!231%M!23-2!23$!('5C1%(!

14<5'2-%:$!5=!02-2$!-%.!65:-6!2->$0!5;$'!2310!<$'15.!C5/6.!3-;$!<-'21-667!5==0$2!23$!.$:61%$!1%!

=$.$'-6!4-'(1%-6!2->!'-2$0?!&/2!C123!$00$%21-667!-66!02-2$0!=-:1%(!054$!=5'4!5=!&-6-%:$.A&/.($2!

'$N/1'$4$%20?!23$!%$:$00-'7!2->!1%:'$-0$0!-%.!0<$%.1%(!:/20!C5/6.!3-;$!/%.5%$!2310!<52$%21-6!

What are the stabilizers?

�

�

:/0315%1%(!$==$:28!

Auerbach et al, ∆Taxes / ∆Income

!"#$%&'()'*$+,-.+"/'0&12,31"4&3&11',5'!&6&%.7'8.9&1'+,':3/,-&

Definition: Rules in tax and transfer systems that lead to

automatic adjustments in revenues and outlays in response

to business cycle fluctuations.

+8O+

How can they affect fluctuations?

+8@"

2. By changing relative benefits and costs.

3. Deficit-financing and crowd out or in of capital.

4. Redistribution and consumption (Oh-Reis Keynesian

channel).

5. Redistribution and labor supply (Oh-Reis neoclassical

channel).

�

Examples: personal income tax, safety net transfers,

corporate income tax, unemployment benefits...

.9Q.P

1. By lowering the volatility of cash on hand, X̂ = (1 − τ )X.

+8@+

+8*"

+8*+

DEF+

DEF"

DEB+

DEB"

DEH+

DEH"

DEE+

DEE"

*+++

*++"

*+D+

P$-'

!

��

StDev(Y (·, τ ) ≈ �

�

i=1

A new measure of stabilization

�

�

���

N ��

��

∂T

∂Y

∂X

∂Y

∂P

�

�

i

i

i

i

StDev(Y (·, τ ) ≈ �

1−

+

� StDev(Z).

�

∂Xi ∂ X̂i ∂Z

∂P ∂Z �

i=1

In a simple model

� with one good, N consumers, aggregate

output is: Y = N

i=1 Yi (P, X̂i , τ ), net income is:

X̂i (Xi , τ ) = Xi − Ti (Xi , τ ), gross income is Xi (Z, τ ) and prices

in equilibrium are: P (Z, τ ) then:

V ar(Y (·, τ )) ≈

N �

�

i=1

∂Yi ∂Xi ∂Yi ∂P �

+

� StDev(Z).

∂P ∂Z �

∂ X̂i ∂Z

!""#$%&%'()#*(+,,(-.-"/0(

V ar(Y (·, 0))

− 1.

V ar(Y (·, 1))

�

∂Ti

∂Xi

Accounting for all the effects

The fraction by which the volatility of aggregate activity Y (·, τ )

would increase if we removed automatic stabilizers (τ = 1 to

τ = 0):

S=

1−

∂Ti

1−

∂Xi

�

∂Yi ∂Xi ∂Yi ∂P

+

∂P ∂Z

∂ X̂i ∂Z

�2

1-/2'*#00(-.-"/(

Preferences:

E0

∞

�

t=0

V ar(Z).

βt

� 3.-"/(#%(+"&#%0(

�1−σ

ψ

c3.-"/(#%(4%"-%&5-0(/#(-+*%(

t (1 − nt )

!"#$%$"&'%

(#()*%+*&,-'%

$.%$")%$#+/)%

(1 − σ)

3.-"/(#%(4%"-%&5-0(/#("#%0$6-(

3.-"/(/7*#$'7('-%-*+,(-8$4,49*4$6((

Wealth evolution:

p̂t ct + bt+1 − bt = pt [xt − τ̄ x (xt )]

Preliminaries

Income

�

Time is discrete, agents live forever, aggregate shocks to

xt = (it /pt )bt +productivity

wt s̄nt + dand

t . monetary policy.

3. A quantitative business-cycle model

�

First automatic

�

x

τ̄ (x) =

Population: measure 1 of capital-owners, measure ν of

other households,

measure 1income

of intermediate-good

firms,

stabilizer

is the personal

tax :

representative final-goods firm, representative capital firms.

x

x �

�

τ (x )dx .

0

�

Government collects taxes τ̄ at rates τ , gives transfers T

and spends resources g.

where τ x is weakly increasing.

�

Capture as many possible stabilizers as can, with three

omissions: closed economy, no health care, no retirement.

2

Capital owners

Insure within, preferences of representative agent:

�

�

∞

2

�

n1+ψ

t

t

E0

β ln(ct ) − ψ1

1 + ψ2

t=0

Wealth evolution:

p̂t ct + bt+1 − bt = pt [xt − τ̄ x (xt )] + Tte

Income:

xt = (it /pt )bt + wt s̄nt + dt .

First stabilizer: personal income tax with τ x weakly increasing:

� x

x

τ̄ (x) =

τ x (x� )dx� .

Other households

Same preferences, but can be more impatient β̂ ≤ β.

Income subject to idiosyncratic shocks:

xt (i) = (it /pt )bt (i)+I(et (i) = 2)st (i)wt nt (i)+T u (et (i), st (i)).

The st (i) are skill shocks, which generate a wage distribution.

Progressive taxation then implies redistribution.

Law of motion for wealth:

p̂t ct (i) + bt+1 (i) − bt (i) = pt [xt (i) − τ̄ x (xt (i))] + pt T n (et (i))

0

Safety-net payments

�

et ∈ {0, 1, 2} is employment status, Markov process.

Probabilities depend on exogenous shock, so have a

business cycle in aggregate unemployment.

�

If et (i) = 2 then employed, earn wage st (i)wt nt (i) as part

of taxable income, and no social benefits: T u = T n = 0.

�

If et (i) = 1 then unemployed collecting benefits, which are

taxable. Unemployment benefits �

�

receive T u (et (i), st (i)) = min T̄ u st (i), T̄ u s̄u if

et (i) = 0. Zero otherwise.

Final goods’ firms

Technology:

��

yt =

1

yt (j)1/µ dj

0

�µ

.

By cost minimization and zero profits:

�

If et (i) = 0 then out of the labor force collecting food

stamps, which are not taxable. SNAP / food stamps

receive T¯n (et (i)) if et (i) = 0. Zero otherwise.

pt =

��

1

pt (j)

0

1/(1−µ)

dj

�1−µ

.

Sales tax

After-tax prices p̂t = (1 + τ c )pt so consume 1/(1 + τ c )

fraction of spending.

Intermediate goods’ firms

Capital goods’ firms

Continuum of monopolists with production function:

yt (j) = at kt (j)α �t (j)1−α .

Maximize after-tax nominal profits dit (j):

�

�

1 − τ k [pt (j)yt (j)/pt − wt �t (j) − (rt + δ)kt (j) − ξ] .

Representative firm, maximize after-tax profits dkt :

(1 − τ k )rt kt − ∆kt+1 − Υ(∆kt+1 )kt .

Value of the firm is

vt = dkt − τ p vt + β Et [λt,t+1 Vt+1 ]

Nominal rigidities a la Calvo (1983) with parameter θ.

Corporate income tax

Flat rate τ k attenuates fluctuations in dividends and in

after-tax interest rate.

Property income tax

Rate τ p on vt = qt kt and qt = 1 + Υ� (.) is procyclical.

The last stabilizer: budget constraint

The government budget constraint is:

�ν

�ν

τ c 0 (ct (i)dh + ct )di + τ p qt kt + 0 τ̄ x (xt (i))dh + τ̄ x (xt ) +

�

�

τ k ω dˆi (j)di + rt kt − γ∆kt+1 =

�ν

�ν

Tte + 0 (1 − eht )Ttuh dh + 0 Tt (xt (i), st (i), et (i))di +

gt + (it /pt )Bt − (Bt+1 − Bt ) /pt

Need a fiscal rule to cover deficits. Tax on entrepreneurs is

closest to being separated from other effects:

� �φ

Bt

e

Tt = log

B̄

But also consider alternative with purchases:

�

�

gt

yt Bt /pt φ

=

g

ȳ

B̄

Market clearing

�

Government bonds are the only asset in positive net supply:

� ν

Bt =

bt (i)di + bt .

0

�

Capital goods:

� 1

kt =

kt (j)dj.

0

�

Labor market:

� 1

�

lt =

�t (j)dj =

0

�

ν

et (i)st (i)nt (i)dh + s̄nt .

0

Taylor rule for monetary policy:

it = ī + φp ∆ log(pt ) + φy log(yt /y) + εt

Equilibrium

�

Aggregate shocks to log(at ) and εt are independent AR(1).

Individual shocks to et (i) and st (i) are Markov processes.

�

Employment varies exogenously with aggregate shocks:

probabilities depend on composite shock log(at ), εt .

�

Our measure of real activity is log output and its variance

is evaluated at the ergodic distribution of this economy.

�

Crucial is that we have four groups of stabilizers:

4. First result: neutrality

1. Proportional taxes τ c , τ k , τ p ;

2. Progressive personal tax system τ x (x� );

3. Safety-net transfers T u (et (i), st (i)), T n (et (i), st (i));

4. Deficits, via adjustment rate φ.

Neutrality proposition

Assumption 1: The following set of conditions holds:

Implications

�

Intuition for the result with separable preferences (σ = 1)

1. With flexible prices, there is an aggregate production

function: yt = at ktα lt1−α .

2. k is fixed so proposition holds if labor supply is fixed.

3. Because g/y is fixed, resource constraint says c/y is fixed.

Because production function is Cobb-Douglas, wages are

proportional to y/l. Therefore, c/w is proportional to l.

4. Because of complete markets, consumption same for all.

5. Labor supply condition for employed household:

1. Households trade a complete set of Arrow securities.

2. The personal income tax is proportional.

3. Probability of employment is fixed over time.

4. Capital is fixed (infinite adjustment costs).

5. Prices are flexible (Calvo frequency is infinity).

6. Government purchases are a fixed fraction of GDP.

Proposition Under the conditions of assumption 1, the

variance of the log of output is equal to the variance of the log

of productivity. Therefore, S = 0 for any combination of taxes

and transfers.

nt (i) = 1 −

�

p̂t

ψct (i)

.

pt (1 − τ )wt st (i)

Implications:

�

�

�

Public finance measures would have led you astray.

Net income affects volatility of the level but not log income.

Proportional taxes are weak stabilizers.

Aggregation result

5. Second result: complete markets

Proposition If all households can trade a complete set of Arrow

securities, there is a representative agent. Her preferences are:

�

�

∞

2

�

n1+ψ

t

t

max E0

β log(ct ) − (1 + Et ) ψ1

1 + ψ2

t=0

and her constraints are:

p̂t ct + bt+1 − bt = pt [xt − τ̄ (xt )] + Ttn

it

xt = bt + wt st (1 + Et )nt + dt + Ttu

pt

�

� 1

� ν

1+1/ψ2

1

Et

1+1/ψ2

1+1/ψ2

st =

s̄t

+

si,t

di

,

1 + Et

1 + Et 0

where 1 + Et is total employment, including capital-owners and

households.

More aggregation results

The United States welfare state

Table 1. The government's use and source of funds, average 1997-2007

Lemma The solution to the capital firm’s problem is

represented by a standard Euler equation, taking into account

the adjustment costs.

Lemma The solution to the final- and intermediate-goods

problems is represented by a standard NK Phillips curve.

Revenues

Outlays

Automatic stabilizers

Automatic stabilizers

Personal Income Taxes

Corporate Income Taxes

Sales and excise taxes

Property Taxes

Others

Public deficit

So, overall, very standard macro model augmented to have

many taxes along many margins.

11.22%

2.59%

3.80%

2.75%

Sum

0.29%

0.91%

0.20%

0.17%

0.35%

0.19%

Others

-1.12%

Out of the model

Customs taxes

Licenses, fines, fees

Payroll taxes

Unemployment benefits

Safety net programs

Supplemental nutrition assistance

Family assistance under PRWORA

Security income to the disabled

Others

Government purchases

Net interest income

15.14%

2.25%

Out of the model

0.21%

1.79%

6.26%

27.49%

Notes

28.61%

Retirement-related transfers

Others (esp. rest of the world)

Health benefits (non-retirement)

Sum

7.27%

1.92%

1.74%

27.49%

Calibration of stabilizers

Simulate TaxSim, 88-07, federal plus state, weight states by

population, years equally. Fit a truncated cubic to it, plus an

intercept to match table 1. Get:

Table 1: Parameter Values

Explanation

Value

Panel A. Tax bases and rates

τc

Tax rate on consumption

0.054

β

Discount factor of stock owners

0.989

τp

Tax rate on property

0.003

α

Coefficient on labor in production

0.296

τk

Tax rate on corporate income

0.282

ξ

Fixed costs of production

1.32

µ

Desired gross markup

1.1

Panel B. Government outlays and debt

Tu

Unemployment benefits

0.185

To

Safety-net transfers

0.169

G/Y

Steady-state purchases / output

0.130

φ

Fiscal adjustment speed

1.33

B/Y

Steady-state debt / output

1.66

Panel C. Labor-force status

πeu

Steady-state transition probability E-U 0.026

πue

Steady-state transition probability U-E 0.571

Table

1: Parameter

πup

Steady-state transition

probability

U-P Values

0.297

πpu

Steady-state transition probability P-E 0.087

y

πeu

Cyclical transition probability E-U

-1.20

y

Parameter

Explanation

Value

πue

Cyclical transition probability U-E

3.477

y

πupA. TaxCyclical

transition

1.55

Panel

bases and

rates probability U-P

Panel

distribution

τc D. Income

Tax rateand

on wealth

consumption

0.054

ν

Non-participants

/

stock

owners

4

β h

Discount factor of stock owners

0.989

Discount

of non-participants

0.983

τpβ

Tax

rate onfactor

property

0.003

s̄

Skill level of stock owners

4.66

α

Coefficient on labor in production

0.296

E(s)

Mean of non-participants skill

1.08

τk

Tax rate on corporate income

0.282

Panel E. Business-cycle parameters

ξ

Fixed costs of production

1.32

γ

Coefficient of relative risk aversion

1

µ

Desired gross markup

1.1

θ

Calvo parameter for price stickiness

0.286

Panel B. Government outlays and debt

ψ

Labor supply

21.6

Tu 1

Unemployment benefits

0.185

ψ

Labor supply

2

To 2

Safety-net transfers

0.169

δ

Depreciation rate

0.114

G/Y

Steady-state purchases / output

0.130

φ

Adjustment costs for investment

17.2

φ

Fiscal adjustment speed

1.33

ρz

Autocorrelation of productivity shock

0.923

B/Y

Steady-state debt / output

1.66

σz

St. dev. of productivity shock

0.003

Panel C. Labor-force status

ρm

Autocorrelation of monetary shock

0.500

πeu

Steady-state transition probability E-U 0.026

σm

St. dev. of monetary shock

0.005

πue

Steady-state transition probability U-E 0.571

φp

Interest-rate rule coefficient on inflation 1.50

πupφ

Steady-state

probability

U-P 0.297

Interest-ratetransition

rule coefficient

on output

0.010

y

πpu

Steady-state transition probability P-E 0.087

y

πeu

Cyclical transition probability E-U

-1.20

y

πue

Cyclical transition probability U-E

3.477

2

y

πup

Cyclical transition probability U-P

1.55

Panel D. Income and wealth distribution

ν

Non-participants / stock owners

4

βh

Discount factor of non-participants

0.983

s̄

Skill level of stock owners

4.66

E(s)

Mean of non-participants skill

1.08

Panel E. Business-cycle parameters

γ

Coefficient of relative risk aversion

1

θ

Calvo parameter for price stickiness

0.286

ψ1

Labor supply

21.6

ψ2

Labor supply

2

δ

Depreciation rate

0.114

φ

Adjustment costs for investment

17.2

ρz

Autocorrelation of productivity shock

0.923

σz

St. dev. of productivity shock

0.003

ρm

Autocorrelation of monetary shock

0.500

σm

St. dev. of monetary shock

0.005

φp

Interest-rate rule coefficient on inflation 1.50

φy

Interest-rate rule coefficient on output

0.010

0.4

Target (Source)

Avg. revenue from sales taxes (Table 1)

Consumption-income ratio = 0.689 (NIPA)

Avg. revenue from property taxes (Table 1)

Capital income share = 0.36 (NIPA)

Avg. revenue from corporate income tax (Table 1)

Corporate profits / GDP = 9.13% (NIPA)

Avg. U.S. markup (Basu, Fernald, 1997)

Avg. outlays on unemp. benefits (Table 1)

Avg. outlays on safety-net benefits (Table 1)

Avg. outlays on purchases (Table 1)

Autocorrelation of net government savings / GDP = 0.966 (NIPA)

Avg. interest expenses (Table 1)

Avg. insured unemp. rate = 0.023 (BLS)

Avg. UE flow quarterly = 0.813 (Shimer, 2007)

Avg. SNAP ratio = 0.077 (USDA)

SNAP exit hazard = 0.03 monthly (Mabli et al., 2011)

St. dev. of unemp. rate = 0.009 (BLS)

Target

(Source)

St. dev.

of UE flows = 0.053 (Shimer)

St. dev. of SNAP ratio = 0.020 (USDA)

Avg. revenue from sales taxes (Table 1)

Consumption-income ratio = 0.689 (NIPA)

Wealth

of topfrom

20% property

by wealthtaxes (Table 1)

Avg.

revenue

Income of top 20% by wealth (SCF)

Capital income share = 0.36 (NIPA)

Avg. income in economy normalized to 1

Avg. revenue from corporate income tax (Table 1)

Corporate profits / GDP = 9.13% (NIPA)

Avg. U.S. markup (Basu, Fernald, 1997)

Avg. price spell duration = 3.5 (Klenow, Malin, 2011)

Avg. hours worked = 0.31 (Cooley, Prescott, 1995)

Avg. outlays on unemp. benefits (Table 1)

Frisch elasticity = 1/2

Avg. outlays on safety-net benefits (Table 1)

Annual depreciation expenses / GDP = 0.046 (NIPA)

Avg. outlays on purchases (Table 1)

Corr. of Y and C = 0.88 (NIPA)

Autocorrelation of net government savings / GDP = 0.966 (NIPA)

Autocorrelation of log GDP = 0.864 (NIPA)

Avg. interest expenses (Table 1)

St. dev. of log GDP = 1.539 (NIPA)

Largest autoregressive root of inflation = 0.85 (Pivetta, Reis, 2006)

Avg. insured unemp. rate = 0.023 (BLS)

Share of output variance due to m shock = 0.8

Avg. UE flow quarterly = 0.813 (Shimer, 2007)

St. dev. of inflation = 0.638 (NIPA)

Avg.

SNAP of

ratio

= 0.077

(USDA)

Correlation

inflation

with

log GDP = 0.198 (NIPA)

SNAP exit hazard = 0.03 monthly (Mabli et al., 2011)

St. dev. of unemp. rate = 0.009 (BLS)

St. dev. of UE flows = 0.053 (Shimer)

St. dev. of SNAP ratio = 0.020 (USDA)

Calibration of inequality

Wealth of top 20% by wealth

Income of top 20% by wealth (SCF)

Avg. income in economy normalized to 1

Avg. price spell duration = 3.5 (Klenow, Malin, 2011)

Avg. hours worked = 0.31 (Cooley, Prescott, 1995)

Frisch elasticity = 1/2

Annual depreciation expenses / GDP = 0.046 (NIPA)

Corr. of Y and C = 0.88 (NIPA)

Autocorrelation of log GDP = 0.864 (NIPA)

St. dev. of log GDP = 1.539 (NIPA)

Largest autoregressive root of inflation = 0.85 (Pivetta, Reis, 2006)

Share of output variance due to m shock = 0.8

St. dev. of inflation = 0.638 (NIPA)

Correlation of inflation with log GDP = 0.198 (NIPA)

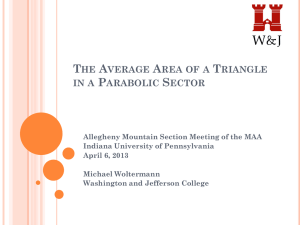

0.35

0.3

Table 1: Parameter Values

0.25

Parameter

marginal tax rate

Parameter

Calibration of personal income tax

Explanation

0.2

Value

Target (Source)

Panel A. Tax bases and rates

0.15on consumption

τc

Tax rate

0.054 Avg. revenue from sales taxes (Table 1)

β

Discount factor of stock owners

0.989 Consumption-income ratio = 0.689 (NIPA)

0.1on property

τp

Tax rate

0.003 Avg. revenue from property taxes (Table 1)

α

Coefficient on labor in production

0.296 Capital income share = 0.36 (NIPA)

τk

Tax rate

0.282 Avg. revenue from corporate income tax (Table 1)

0.05on corporate income

ξ

Fixed costs of production

1.32 Corporate profits / GDP = 9.13% (NIPA)

µ

Desired gross

markup

1.1

Avg. U.S. markup (Basu, Fernald, 1997)

0

Panel B. Government outlays and debt

u

T

Unemployment

benefits

0.185 Avg. outlays on unemp. benefits (Table 1)

−0.05

To

Safety-net transfers

0.169 Avg. outlays on safety-net benefits (Table 1)

G/Y

Steady-state

purchases / output

0.130 Avg. outlays on purchases (Table 1)

−0.1

φ

Fiscal adjustment

speed

savings / GDP = 0.966 (NIPA)

0

1

2

31.33 Autocorrelation

4

5 of net government

6

7

income

B/Y

Steady-state debt / output multiples of average

1.66 household

Avg. interest

expenses (Table 1)

Panel C. Labor-force status

πeu

Steady-state transition probability E-U 0.026 Avg. insured unemp. rate = 0.023 (BLS)

πue

Steady-state transition probability U-E 0.571 Avg. UE flow quarterly = 0.813 (Shimer, 2007)

πup

Steady-state transition probability U-P 0.297 Avg. SNAP ratio = 0.077 (USDA)

πpu

Steady-state transition probability P-E 0.087 SNAP exit hazard = 0.03 monthly (Mabli et al., 2011)

y

πeu

Cyclical transition probability E-U

-1.20 St. dev. of unemp. rate = 0.009 (BLS)

y

πue

Cyclical transition probability U-E

3.477 St. dev. of UE flows = 0.053 (Shimer)

y

πup

Cyclical transition probability U-P

1.55 St. dev. of SNAP ratio = 0.020 (USDA)

Panel D. Income and wealth distribution

ν

Non-participants / stock owners

4

βh

Discount factor of non-participants

0.983 Wealth of top 20% by wealth

s̄

Skill level of stock owners

4.66 Income of top 20% by wealth (SCF)

E(s)

Mean of non-participants skill

1.08 Avg. income in economy normalized to 1

Panel E. Business-cycle parameters

γ

Coefficient of relative risk aversion

1

θ

Calvo parameter for price stickiness

0.286 Avg. price spell duration = 3.5 (Klenow, Malin, 2011)

ψ1

Labor supply

21.6 Avg. hours worked = 0.31 (Cooley, Prescott, 1995)

ψ2

Labor supply

2

Frisch elasticity = 1/2

δ

Depreciation rate

0.114 Annual depreciation expenses / GDP = 0.046 (NIPA)

φ

Adjustment costs for investment

17.2 Corr. of Y and C = 0.88 (NIPA)

ρz

Autocorrelation of productivity shock

0.923 Autocorrelation of log GDP = 0.864 (NIPA)

σz

St. dev. of productivity shock

0.003 St. dev. of log GDP = 1.539 (NIPA)

ρm

Autocorrelation of monetary shock

0.500 Largest autoregressive root of inflation = 0.85 (Pivetta, Reis, 2006)

σm

St. dev. of monetary shock

0.005 Share of output variance due to m shock = 0.8

φp

Interest-rate rule coefficient on inflation 1.50 St. dev. of inflation = 0.638 (NIPA)

φy

Interest-rate rule coefficient on output

0.010 Correlation of inflation with log GDP = 0.198 (NIPA)

Calibration of other parameters

2

resulting government budget surplus is rebated lump-sum to capital owners.

investment more volatile.

The policy changes would generally raise the steady state level of output because they reduce

4. small government: no government spending, transfers are reduced to 20% of their baseline

distortions. The high marginal tax rates associated with progressive taxation have quite large

C

K

P

level, income taxes are eliminated, τ , τ , and τ are reduced by 10%. Steady state goveffects on steady state levels. The elimination of government spending in the small government

ernment debt remains at itsThe

baseline

level. A lump-sum tax on capital owners balances the

experiments

Results

for S

experiment has a large, if mechanical,

effect on consumption.

budget period by period.

3

1. lower proportional taxes: tax rates τ C , τ P and τ K are

10%. Lost revenue of 0.6% of GDP is replaced

Resultsreduced

for thebyrepresentative

agent economy

by increased lump-sum tax on the capital owners.

In the representative agent economy, the effects of these policies for fluctuations are modest. In

2. without

progressive

taxes:

the slightly

progressive

incomebut

tax

particular, lowering

transfers

would make the

economy

more stable,

in essence has no

effect on volatilities.

Progressive

has veryincome

little effect

output

or the

labor input, but does

is replaced

by ataxation

proportional

tax on

that

raises

contribute to the

stability

of consumption.

My understanding of this result is that it is driven

same

revenue

in steady state.

by intertemporal substitution in the timing of dividends: in a recession, marginal tax rates are

lower and it 3.

is an

attractive

time to

pay out dividends.

Thistomakes

more stable and

low

transfers:

transfers

are reduced

lowerconsumption

spending by

investment more0.8/5

volatile.

of GDP. In steady state, the resulting government

The policy changes would generally raise the steady state level of output because they reduce

budget

surplus is rebated lump-sum to capital owners.

distortions. The high marginal tax rates associated with progressive taxation have quite large

effects on steady state levels. The elimination of government spending in the small government

4. small

no on

government

spending, income

experiment has

a large, government:

if mechanical, effect

consumption.

taxes are eliminated, all other taxes and transfers fall by

amounts

equal to above experiments. Steady state

Table 1: S statistic for representative agent economy

government debt remains at its baseline level. A lump-sum

tax

capital

owners

balances the

budget

every period.

low on

propor.

taxes

w/o progressive

taxes

low transfers

small gov.

Y

N

C

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

0.0047

0.0078

-0.0254

-0.0119

0.0019

0.0746

-0.0059

-0.0056

-0.0168

-0.0147

-0.0080

0.0721

Effect on steady state

Table 1: S statistic for representative agent economy

Y

N

C

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0047

0.0078

-0.0254

-0.0119

0.0019

0.0746

-0.0059

-0.0056

-0.0168

-0.0147

-0.0080

0.0721

Progressive income tax only stabilizes C because of timing of

Table 2: Effects on steady state levels for representative agent economy

dividends by capital-goods firm. Transfers not exactly zero

because

taxable, but very close to Ricardian equivalence.

low propor. taxes w/o progressive taxes low transfers small gov.

Y

N

C

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

0.0159

0.0007

0.0147

0.0369

0.0369

0.0487

0.0002

0.0002

0.0002

0.0321

0.0167

0.2655

2

Table 2: Effects on steady state levels for representative agent economy

Y

N

C

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0159

0.0007

0.0147

0.0369

0.0369

0.0487

0.0002

0.0002

0.0002

0.0321

0.0167

0.2655

Progressive taxation comes with much lower output though

2

because of its high marginal tax rates.

6. Third result: heterogeneity

Solving the full model

�

�

4

Need to solve a model with:

�

Heterogeneity: must keep track of distributions, as in

Krusell and Smith (1997).

�

Nominal rigidities: as in Oh and Reis (2011) and Guerrieri

and Lorenzoni (2011).

�

Solve for aggregate dynamics: as in Reiter (2009)

We have just finished refining our grids (so no draft yet but

very soon).

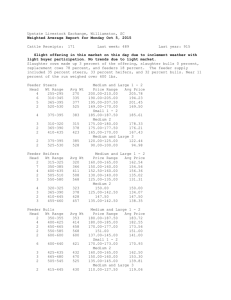

How the model works: household savings

employed

1.5

the model works:

capital

Results forHow

the heterogeneous

agent economy

i

The steady state effects are similar to the representative agent economy, but the impact on volatilities are now more substantial.

Transfers in particular have a substantially larger effect here and the

h −1

variance of log output is 13% higher when transfers are reduced. However, aggregate consumption

is more stable when transfers are reduced. This result is driven by the additional accumulation of

precautionary savings in the stationary economy. Lowering /01"#20*.%

transfers increases the precautionary

3'4)-5"%

savings motive of households, which means that they have more

savings with which to smooth

aggregate as well

as

idiosyncratic

shocks.

To

confirm

this

intuition,

we conducted an additional

−1

e

experiment in which we lower the households’ discount factor at the same time that we eliminate

transfers. This experiment is just meant to illustrate the role678,%9'()$'*%"$09:%

of precautionary savings in the model

and is not intended as a true policy experiment because it is not clear how one might achieve this

reduction in discount factor. We choose the new discount factor so that the aggregate assets of

678,% economy despite the fact that transfers are lower. In

the households is the same as in the baseline

201"#20*.%

this alternative economy with low transfers

and a low discount &'()$'*%+#,'-.%

factor, the volatility of consumption

is higher than in the baseline economy"'4)-5"%

by 22% (i.e. S = 0.22). This makes sense as in this case

the households have little private insurance in the form of precautionary savings and little public

insurance in the form of transfers. Therefore, the reduction in employment in a recession has a

strong impact on consumption.

The impact of progressive taxation on the volatility of output is now substantially larger than in

!""#$"%

the representative agent economy. However, while progressive taxation stabilized

consumption in

the representative agent economy, it now destabilizes log consumption. This result also arises out

of the impact of the policy on the steady state. The change to proportional taxes makes the level

of consumption more volatile and larger in steady state. These two effects have opposite effects

on the variance of log consumption. The impact on steady state consumption is stronger in the

Results

S increase in the volatility of the level

heterogeneous agent economy and this

is enough tofor

offset the

of consumption.

�

β

�

(β )

1

Table 3: S statistic for heterogeneous agent economy

0.5

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

unemployed

1

Y

N

C

0.5

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0036

0.0125

0.0424

0.1454

0.1348

-0.0663

0.1317

0.0640

-0.2270

0.1278

0.1364

-0.0716

1

out of the labor force

5

1

baseline

low transfers

Proportional taxes still mostly irrelevant. Our first extreme

Alternative

Financing

Mechanisms

result is still

a good approximation.

1. Baseline: lump-sum tax adjusts gradually to government debt outstanding.

0.5

2. No deficits: lump-sum tax immediately to clear government budget.

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

assets (1 = avg income)

0.8

1

3. Spending: G adjusts gradually to debt outstanding.

3

of the impact of the policy on the steady state. The change to proportional taxes makes the level

of consumption more volatile and larger in steady state. These two effects have opposite effects

on the variance of log consumption. The impact on steady state consumption is stronger in the

heterogeneous agent economy and this is enough to offset the increase in the volatility of the level

Results for S

of consumption.

of consumption more volatile and larger in steady state. These two effects have opposite effects

on the variance of log consumption. The impact on steady state consumption is stronger in the

heterogeneous agent economy and this is enough to offset the increase in the volatility of the level

of consumption.

Results for S

Table 3: S statistic for heterogeneous agent economy

Table 3: S statistic for heterogeneous agent economy

Y

N

C

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0036

0.0125

0.0424

0.1454

0.1348

-0.0663

0.1317

0.0640

-0.2270

0.1278

0.1364

-0.0716

Progressive taxes much more effective at stabilizing output and

5 Alternative

Financing

Mechanisms

employment,

but now destabilize

consumption. Actually C is

more

stable

in

levels,

but

steady-state

level much

so log

1. Baseline: lump-sum tax adjusts gradually to government

debtlower,

outstanding.

C is more volatile.

2. No deficits: lump-sum tax immediately to clear government budget.

Y

N

C

5

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0036

0.0125

0.0424

0.1454

0.1348

-0.0663

0.1317

0.0640

-0.2270

0.1278

0.1364

-0.0716

Transfers are hugely effective on Y, N but destabilize C. With

Alternative

Financing

Mechanisms

low transfers,

precautionary

savings rise allowing for better

smoothing

of shocks.

1. Baseline:

lump-sum

tax adjusts gradually to government debt outstanding.

2. No deficits:

lump-sum

taxhousehold

immediatelydiscount

to clear government

budget.

Experiment:

lower

factor. Now

S for

consumption

+22%. to debt outstanding.

3. Spending:

G adjustsisgradually

3. Spending: G adjusts gradually to debt outstanding.

3

3

Wealth distribution

Results for steady state

employed

0.015

0.01

Table 4: Effects on steady state levels for heterogeneous agent economy

0.005

0

0

2

−4

4

4

6

8

10

unemployed

x 10

Y

N

C

3

2

1

0

0

2

4

6

8

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

0.0164

0.0012

0.0153

0.0413

0.0413

0.0543

0.0017

0.0017

0.0024

0.0347

0.0192

0.2696

10

out of the labor force

0.015

baseline

low transfers

0.01

0.005

0

low propor. taxes

(1)

0

2

4

6

assets (1 = avg income)

8

10

Keynesian effect on bottom group, stabilizes Y,N.

Precautionary effect on other households, C destabilized.

The timing

of the lump-sum

tax hasimpacts

very littleoninfluence

the dynamics

Transfers

have minimal

steady on

state,

unlike of the economy, which

reflects a near

Ricardian

equivalence.

The

reason

that

Ricardian

equivalence

does not hold exactly

progressive taxes.

is that the interest payments on government debt alters taxable income. A fiscal adjustment rule

that has government spending adjust to stabilize government debt leads output and hours to be

more volatile, but consumption to be less volatile. The reason that hours are more volatile is

because of a wealth effect: in a boom, government revenues rise as the tax base increases and

government outlays fall as transfers fall. These forces lead to a reduction in government debt,

which is offset by increased government spending, which generates a wealth effect that increases

labor supply thus reinforcing the boom. This wealth effect also leads consumption to respond less

in a boom making it more stable. The same pattern arises in the representative agent economy.

because of a wealth effect: in a boom, government revenues rise as the tax base increases and

government outlays fall as transfers fall. These forces lead to a reduction in government debt,

which is offset by increased government spending, which generates a wealth effect that increases

labor supply thus reinforcing the boom. This wealth effect also leads consumption to respond less

in a boom making Alternative

it more stable. The same

pattern arises mechanisms

in the representative agent economy.

financing

Keynes or Precautionary?

Table 6: S statistic for hand-to-mouth economy

Table 5: Variance of logs for heterogeneous agent economy

Y

N

C

6

baseline

no deficits

spending

0.0166

0.0135

0.0190

0.0166

0.0135

0.0188

0.0185

0.0156

0.0122

Running deficits is almost irrelevant. Ricardian equivalence not

Results

for hand-to-mouth economy

such a bad approximation.

In this version of the model we assume that the households do not save and consume their after-tax

Government

leads

to calibration

large wealth

effects.

incomes immediately.

I didpurchases

not changeadjusting

any features

of the

except

that I increased the

because

in booms,

surplus, This

leadschange

to rises

coefficients inIncreases

the Taylorvolatility

rule to resolve

an issue

of non-existence.

mayinalter the overall

dynamics in G,

response

a shock,

I hope it will not effect the impact of the experiments too

whichtoare

furtherbut

expansionary.

much.

It is still the case that lowering proportional taxes has close to no effect on volatility. Progressive

taxes also have very limited impact, which is more similar to the representative agent economy

than the heterogeneous agent economy. Reducing transfers now makes consumption more volatile,

which is not surprising as a large part of consumption tracks income mechanically. In this economy,

transfers stabilize labor supply more than in the heterogeneous agent economy. The behavior of

labor supply in the transfer experiment depends in part on the way the transfers are financed.

If we conduct the same experiment under the assumption that government spending adjusts to

4

Y

N

C

low propor. taxes

(1)

w/o progressive taxes

(2)

low transfers

(3)

small gov.

(4)

-0.0002

0.0091

-0.0074

-0.0052

0.0217

0.0210

0.0280

0.0950

0.1518

0.0481

0.1362

0.1043

maintain long-run

budget

balance, then the

volatility

hourshouseholds

is nearly unchanged

by the change

Mankiw’s

savers-spenders,

just

assumeof that

live

in transfers.hand-to-mouth.

One effect of transfers under lump-sum financing is that a positive shock leads to a

positive wealth effect for the capital-owners since they will pay fewer taxes for the transfers. This

is stabilizing since the positive wealth effect leads them to work less. When government spending

Transfers now mechanically stabilize consumption, and because

is used to balance the budget, the positive shock leads to an increase in government spending to

in recession, lump-sum tax on entrepreneurs rises, they work

absorb the budget surplus so there is not the same wealth effect.

more, which is also stabilizing.

Conclusion

�

Follow the money: transfers, tax changes. Focus on

automatic stabilizers.

Contributions / results

7. Conclusion

�

Propose a new measure of stabilization. New method to

solve incomplete-market models with nominal rigidities.

�

Redistribution is the crucial stabilizing force.

�

Progressive taxation and safety-net transfers stabilize

output and hours, but not consumption.

�

Transfers cause small reductions in steady-state wealth.