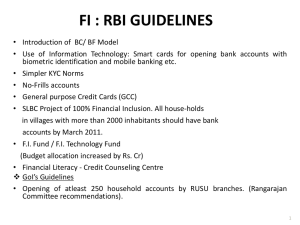

Banking Correspondent Linkages and Financial Inclusion Strategies

advertisement