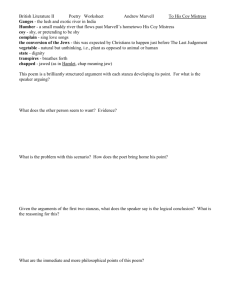

Nick's Notes

advertisement