articles on roads in rainforests

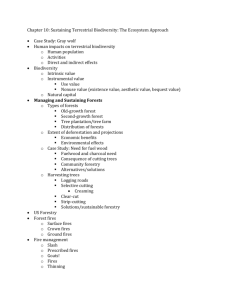

advertisement

Railroad could reduce Amazon deforestation relative to proposed highway mongabay.com March 24, 2008 Building a railroad instead of improving a major highway could reduce deforestation and biodiversity loss in the heart of the Amazon rainforest says an Brazilian environmental group. The Institute for Conservation and Sustainable Development of Amazonas (IDESAM), together with the state of Amazonas, have teamed up to host a debate on the paving of BR319, a highway that links the capital cities of Manaus and Porto-Velho, but is presently impassable. Environmentalists say that paving the road could increase deforestation pressures in Amazonas, a state where 98 percent of the forest is still intact. Instead, IDESAM and Amazon propose building a railway system between the cities. "Building a railway system would have considerably less impact, avoiding a great deal of the forest loss predicted for the future, while still achieving the economic benefits associated with improving the transportation infrastructure within the Brazilian Amazon," said IDESAM in a statement. The railroad would facilitate the transport of goods from Manaus, a major manufacturing center, to the rest of Brazil. At the same time a railway could avoid the deforestation associated with the establishment and improvement of road networks. Settlers, land speculators and developers often use roads to penetrate previously inaccessible forest areas: data from Brazil's Ministry of the Environment show that from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s, approximately 75 percent of the deforestation in the Amazon occurred near paved roads. This map demonstrates that deforestation up to 2006 (light yellow) is concentrated along roads and waterways. Source: Soares-Filho et al., (Unpublished), based on data from the PRODES Program, Brazilian National Institute for Space Studies Still, there is intense pressure from development interests to pave the BR-319. Through the Avança Brasil program, Brazil has proposed $43 billion in infrastructure improvement and expansion projects in the region through the year 2020. Improved infrastructure can improve the economic viability of logging, cattle ranching, and agricultural products like soybeans and sugar cane. Read more at http://news.mongabay.com/2008/0324-amazon.html#juOGVm05ZeV4Q1gy.99 TREE-974; No of Pages 4 Forum New strategies for conserving tropical forests Rhett A. Butler1 and William F. Laurance2 1 2 Mongabay.com, P.O. Box 0291, Menlo Park, CA 94026, USA Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092, Balboa, Ancón, Panama In an interval of just 1–2 decades, the nature of tropical forest destruction has changed. Rather than being dominated by rural farmers, tropical deforestation now is substantially driven by major industries and economic globalization, with timber operations, oil and gas development, large-scale farming and exotic-tree plantations being the most frequent causes of forest loss. Although instigating serious challenges, such changes are also creating important new opportunities for forest conservation. Here we argue that, by increasingly targeting strategic corporations and trade groups with publicpressure campaigns, conservation interests could have a much stronger influence on the fate of tropical forests. Introduction Tropical forests are the Earth’s biologically richest ecosystems and play vital roles in regional hydrology, carbon storage and the global climate [1,2]. Yet destruction of tropical forests continues apace, with some 13 million hectares of forest felled or razed each year [3]. Although this rate has not changed markedly in recent decades [3], the fundamental drivers of deforestation are shifting – from mostly subsistence-driven deforestation in the 1960s through 1980s, to far more industrial-driven deforestation more recently [4–6]. This trend, we assert, has key implications for forest conservation. From the 1960s to 1980s, tropical deforestation was largely promoted by government policies for rural development, including agricultural loans, tax incentives and road construction, in concert with rapid population growth in many developing nations [4–6]. These initiatives, especially evident in countries such as Brazil and Indonesia, prompted a dramatic influx of colonists into frontier areas and frequently caused rapid forest destruction. The notion that small-scale farmers and shifting cultivators were responsible for most forest loss [7] led to conservation approaches, such as Integrated Conservation and Development Projects (ICDP), that attempted to link nature conservation with sustainable rural development [8]. Many, however, now believe that ICDPs have largely failed because of weaknesses in their design and implementation and because local peoples typically use ICDP funds to bolster their incomes, rather than to replace the benefits they gain from exploiting nature [9–13]. More recently, the direct impact of rural peoples on tropical forests appears to have stabilized and could even Corresponding author: Laurance, W.F. (laurancew@si.edu). be diminishing in some areas. Although many tropical nations still have quite high population growth, strong urbanization trends in developing nations (except in Sub-Saharan Africa) mean that rural populations are growing more slowly, and in some nations are beginning to decline (Figure 1) [14,15]. The popularity of large-scale frontier-colonization programs has also waned in several countries [5,16,17]. If such trends continue, they might alleviate some pressures on forests from small-scale farming, hunting and fuelwood gathering [18]. At the same time, globalized financial markets and a worldwide commodity boom are creating a highly attractive environment for the private sector [5,6]. As a result, industrial logging, mining, oil and gas development and especially large-scale agriculture are increasingly emerging as the dominant causes of tropical forest destruction [6,19–22]. In Brazilian Amazonia, for instance, large-scale ranching has exploded, with the number of cattle more than tripling (from 22 to 74 million head) since 1990 [23], while industrial logging and soy farming have also grown dramatically [24,25]. Surging demand for grains and edible oils, driven by the global thirst for biofuels and rising standards of living in developing countries, is helping to spur this trend [19,26,27]. Although we and others are alarmed by the rise of industrial-scale deforestation (Figure 2), we argue here that it also signals emerging opportunities for forest protection and management. Rather than attempting to influence hundreds of millions of forest colonists in the tropics – a daunting challenge, at best – proponents of conservation can now focus their attention on a vastly smaller number of resource-exploiting corporations. Many of these are either multinational firms or domestic companies seeking access to international markets [6,19–22], which compels them to exhibit some sensitivity to the growing environmental concerns of global consumers and shareholders. When they err, such corporations can be vulnerable to attacks on their public image. Confronting corporations Today, few corporations can easily ignore the environment. Conservation groups are learning to target corporate transgressors, mobilizing support via consumer boycotts and public-awareness campaigns. For example, following an intense public crusade, Greenpeace recently pressured the largest soy crushers in Amazonia to implement a moratorium on soy processing, pending development of a tracking mechanism to ensure their crop is 0169-5347/$ – see front matter . Published by Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.006 Available online xxxxxx 1 TREE-974; No of Pages 4 to favor more-sustainable timber products [29]. Under threats of negative publicity, RAN has even convinced some of the world’s biggest financial firms, including Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup and Bank of America, to modify their lending and funding practices for forestry projects [30]. Recent trends are making it easier for conservation groups to sway resource-exploiting industries. Because of economies of scale, multinational corporations often find it more efficient to concentrate their activities in just a few large countries, thereby reducing the number of geographic areas that conservation groups must actively monitor. Moreover, many industries, motivated by fears of negative publicity, are establishing coalitions that claim to promote environmental sustainability among their members. Examples of such industry groups include Aliança da Terra for Amazonian cattle ranchers [31], the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil in Southeast Asia and the Forest Stewardship Council for the global timber industry. Hence, rather than targeting hundreds of different corporations, conservationists can have a big impact by striking just a few industrial pressure points. Corporations are also being swayed by carrots as well as sticks. Firms that buy into sustainability enjoy growing consumer preferences and premium prices for their ecofriendly products. According to industry sources [32], for example, ‘green’ timber products – those produced in an environmentally sustainable manner – accounted for $7.4 billion in sales in the United States in 2005, and are expected to grow to $38 billion there by 2010. Such rewards might have greater leverage with multinational corporations, which must attempt to keep their international consumers and shareholders happy, than with local firms operating solely in developing countries [33]. Figure 1. Changing urban (red) and rural (blue) populations in major Latin American, Asian and African tropical nations, respectively, from 1950 to 2030, using estimates and future projections from the UN Population Division [14]. coming from environmentally responsible producers [28]. Earlier boycotts by the Rainforest Action Network (RAN) prompted several major U.S. retail chains, including Home Depot and Lowe’s, to alter their buying policies 2 New challenges The rising impact of corporate deforesters also has serious downsides. Industrialization can accelerate forest destruction, with forests that once were laboriously hand cleared by small-scale farmers now being quickly overrun by bulldozers. Moreover, industrial activities such as logging, mining and oil and gas developments promote deforestation not only directly but also indirectly, by creating a powerful economic impetus for forest-road building. Once constructed, such roads can unleash uncontrolled forest invasions by colonists, hunters and land speculators [20,21,24]. Another big problem is that not all markets respond to environmental priorities. In many developing nations, environmental concerns are being swamped by burgeoning demands from a growing middle class. For instance, Asian consumers have so far shown little interest in eco-certified timber products [34], unlike consumers in North America and especially Europe. Moreover, as prices for raw materials soar, an all-out scramble for natural resources could ensue, rendering environmental sustainability a mere afterthought to meeting growing needs. Finally, even an abundance of eco-conscious consumers cannot guarantee good corporate behavior (see Box 1). Many corporations have been accused of ‘greenwashing’ – producing ostensibly green products that actually have TREE-974; No of Pages 4 Figure 2. Changing drivers of deforestation: small-scale cultivators versus industrial road construction in Gabon, central Africa (photos by W.F.L.). little environmental benefit. In the tropical timber industry, for instance, some dubious, industry-sponsored groups have tried to compete with legitimate eco-certification bodies such as the Forest Stewardship Council [35]. Tracking products from the forest to final consumers – via chains of middlemen, manufacturers and retailers – can also be maddeningly difficult. For example, Greenpeace [36] recently revealed that food giants such as Nestlé, Procter and Gamble, and Unilever were using palm oil grown on Box 1. Challenges for eco-certification In the tropics, as elsewhere, eco-certification schemes face some tall hurdles. Even when customers favor eco-friendly products, ecocertification can be hampered by corruption and weak governance, ineffective measures to ensure environmental sustainability and leakage of noncertified products into markets. For instance, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), often viewed as the gold standard for certification of wood products, has been heavily criticized by some environmental groups [40]. Critics say FSC certification of products from ‘mixed sources,’ such as furniture derived only partly from certified wood, hurts its credibility. Certification of some dubious timber schemes, such as plantation monocultures on former forest lands, has also harmed the label [40]. Last year an inquiry by the Wall Street Journal forced the FSC to effectively revoke certification of the Singapore-based Asia Pulp and Paper Company because of its environmentally damaging activities on the Indonesian island of Sumatra [41]. Corruption and fraud are also concerns. Collaboration with corrupt officials allows some companies to falsely certify their products, whereas other firms have claimed to have certification when they do not. A recent report on illegal logging in Southeast Asia, for instance, revealed that at least two major furniture firms were marketing products as eco-certified when they had no such label [42]. Another challenge is properly evaluating the sundry activities of international timber corporations. Eco-certifiers have been accused of focusing too narrowly on logging operations inside core conservation areas while ignoring damaging operations elsewhere [40]. In addition, timber corporations frequently buy timber from various sources and subcontract to other firms, and it can be very difficult to determine whether these subsidiaries and partners are engaged in damaging logging [36]. Finally, some critics argue that even eco-certified timber operations are rarely sustainable in the long term. Repeated logging of old-growth forest can reduce carbon stocks and degrade habitat for forest specialists, thereby threatening biodiversity [1]. Further, logged forests are more vulnerable to desiccation, fires and deforestation than are unlogged areas [24,43]. recently deforested lands, despite assurances to the contrary from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Such complications reward cheaters and diminish the benefits for corporations that make a good-faith effort toward sustainability. The future Despite such complications, conservationists must learn to deal effectively and forcefully with the corporate drivers of tropical deforestation. Such drivers will certainly increase in the future because global industrial activity is expected to expand 300–600% by 2050, with much of this growth in developing countries [37]. For their part, an increasing number of corporations are realizing that environmental sustainability is simply good business. In light of such trends, we see much need for dialogue and debate among industrial, scientific and conservation interests in the tropics. Aside from the influence of environmental groups, the impacts of industry will also be mediated by government policies and by international agreements, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity. For instance, massive U.S. government subsidies for corn ethanol are currently creating market distortions that promote deforestation in the Amazon [23], whereas international carbon trading could eventually slow rapid forest destruction in certain countries [38,39]. Because such policies can change rapidly and have far-reaching implications, conservationists ignore them at their peril. Change is upon us. On the one hand, rapid globalization and industrial farming, logging, mining and biofuel production are emerging as the dominant drivers of tropical deforestation. On the other hand, growing public concerns about environmental sustainability are creating important new opportunities for forest protection. By targeting strategic industries with consumer-education campaigns, conservation interests could gain powerful new weapons in the battle to slow harmful forest destruction. Acknowledgements We thank Thomas Rudel, Robert Ewers, Susan Laurance, Katja Bargum and three anonymous referees for many helpful comments. 3 TREE-974; No of Pages 4 References 1 Laurance, W.F. (1999) Reflections on the tropical deforestation crisis. Biol. Conserv. 91, 109–117 2 Fearnside, P.M. (1997) Environmental services as a strategy for sustainable development in rural Amazonia. Ecol. Econ. 20, 53–70 3 FAO (2005) Global Forest Resources Assessment. UN Food and Agriculture Organisation 4 Geist, H.J. and Lambin, E. (2002) Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. Bioscience 52, 143–150 5 Rudel, T.K. (2005) Tropical Forests: Regional Paths of Destruction and Regeneration in the Late 20th Century. Columbia University Press 6 Rudel, T.K. (2005) Changing agents of deforestation: from stateinitiated to enterprise driven processes, 1970–2000, Land Use Policy 24, 35–41 7 Myers, N. (1993) Tropical forests: the main deforestation fronts. Environ. Conserv. 20, 9–16 8 McNeely, J.A. (1988) Economics and Biological Diversity: Developing and Using Incentives to Conserve Biological Resources, IUCN 9 Brandon, K.E. and Wells, M. (1992) Planning for people and parks: design dilemmas. World Dev. 20, 557–570 10 Ferraro, P.J. (2001) Global habitat protection: limitations of development interventions and a role for conservation performance payments. Conserv. Biol. 15, 990–1000 11 Johannesen, A.B. and Skonhoft, A. (2005) Tourism, poaching and wildlife conservation: what can integrated conservation and development projects accomplish? Resour. Energy Econ. 27, 208–226 12 Strusaker, T.T. et al. (2005) Conserving Africa’s rain forests: problems in protected areas and possible solutions. Biol. Conserv. 123, 45–54 13 Kramer, R. et al. (1997) Last Stand, Oxford University Press 14 UN (2004) World Urbanization Prospects: The 2003 Revision. UN Population Division 15 Montgomery, M. and National Research Council on Urban Population Dynamics (2003) Cities Transformed: Demographic Change and Its Implications in the Developing World, National Academy Press 16 Fearnside, P.M. (1997) Transmigration in Indonesia: lessons from its environmental and social impacts. Environ. Manage. 21, 553–570 17 Barreto, P. et al. (2006) Human Pressure on the Brazilian Amazon Forests. World Resources Institute 18 Wright, S.J. and Muller-Landau, H.C. (2006) The future of tropical forest species. Biotropica 38, 287–301 19 Von Braun, J. (2007) The World Food Situation: New Driving Forces and Required Actions. International Food Policy Research Institute 20 Fearnside, P.M. (2007) Brazil’s Cuiabá-Santarém (BR-163) highway: the environmental cost of paving a soybean corridor through the Amazon. Environ. Manage. 39, 601–614 21 Laurance, W.F. et al. (2004) Deforestation in Amazonia. Science 304, 1109–1111 22 Nepstad, D.C. et al. (2006) Globalization of the Amazon soy and beef industries: opportunities for conservation. Conserv. Biol. 20, 1595–1604 23 Smeraldi, R. and May, P.H. (2008) The Cattle Realm: A New Phase in the Livestock Colonization of Brazilian Amazonia, Amigos da Terra (Friends of the Earth) Amazônia Brasileira 4 24 Laurance, W.F. (1998) A crisis in the making: responses of Amazonian forests to land use and climate change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 411–415 25 Fearnside, P.M. (2001) Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environ. Conserv. 28, 23–38 26 Laurance, W.F. (2007) Switch to corn promotes Amazon deforestation. Science 318, 1721 27 Scharlemann, J. and Laurance, W.F. (2008) How green are biofuels? Science 319, 52–53 28 Kaufman, M. (2007) New allies on the Amazon. Washington Post 24 April (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/ 04/23/AR2007042301903.html) 29 Gunther, M. (2004) Boycotts on timber products. Fortune Magazine 31 May (http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2004/ 05/31/370717/index.htm) 30 Graydon, N. (2006) Rainforest Action Network: the inspiring group bringing corporate America to its senses. The Ecologist 16 February (http://www.ran.org/media_center/news_article/?uid=1849) 31 Butler, R.A. (2007) Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon? (http://news.mongabay.com/2007/0607-carter_interview. html); posted June 7 32 Yaussi, S. (2006) Year of the green builder. Big Builder Magazine 15 April (http://www.bigbuilderonline.com/industry-news.asp?sectionID= 367&articleID=303214) 33 Laurance, W.F. et al. (2006) Impacts of roads and hunting on central African rainforest mammals. Conserv. Biol. 20, 1251–1261 34 Gale, F. (2006) The Political Economy of Sustainable Development in the Asia-Pacific: Lessons of the Forest Stewardship Council Experience. University of Melbourne In: http://www.politics.unimelb.edu.au/ocis/ Gale.pdf) 35 Alter, A. (2007) Green or greenwashing? (http://www.treehugger.com/ files/2007/10/greenwashing_in.php); posted 25 October. 36 Greenpeace (2008) How the palm oil industry is cooking the climate (http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/international/press/reports/ palm-oil-cooking-the-climate.pdf); posted 8 November. 37 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Opportunities and Challenges for Businesses and Industry. Island Press 38 Gullison, R.E. et al. (2007) Tropical forests and climate policy. Science 316, 985–986 39 Laurance, W.F. (2008) Can carbon trading save vanishing forests? Bioscience 58, 286–287 40 Hance, J.L. (2008) The FSC is the ‘Enron of forestry’ says rainforest activist (http://news.mongabay.com/2008/0417-hance_interview_ counsell.html); posted 17 April 41 Wright, T. and Carlton, J. (2007) FSC’s ‘green’ label for wood products gets growing pains. Wall Street Journal 30 October, p. B1 42 EIA/Telapak (2008) Borderlines: Vietnam’s Booming Furniture Industry and Timber Smuggling in the Mekong Region (http:// www.eia-international.org/files/reports160-1.pdf). 43 Asner, G.P. et al. (2008) Condition and fate of logged forests in the Brazilian Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 12947–12950 Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon - Pr... Page 1 of 3 Please consider the environment before printing | PDF version Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon Jeremy Hance mongabay.com September 13, 2009 Oil company in Ecuador transforms indigenous community into commercial poachers, threatening wildlife in a protected area The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador's Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call "one of the most species diverse forests in the world"—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest. By building a 149 kilometer (92 mile) road through the protected forest and providing subsidies to the local tribes, the oil company Maxus Ecuador Inc. transformed some members of the tribes from semi-nomadic subsistence hunters into commercial poachers. "We’ve found that a road in a forest can bring huge social changes to local groups and the ways in which they utilize wildlife resources," said Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) researcher Esteban Suárez, lead author of the study. "Communities existing inside and around the park are changing their customs to a lifestyle of commercial hunting, the first stage in a potential overexploitation of wildlife." According to the new study by the WCS and the IDEASUniversidad San Francisco The collared peccary made up 7.3 percent of the hunted mammals, birds, de Quito in Ecuador, the and reptiles in the study. It's close relative the white-lipped peccary made up 47.9 percent. Photo by: Julie Larsen Maher © WCS. creation of the single road allowed tribe members to transport game to a market where it is sold illegally. In addition, the subsidies and free access to the road, all provided by the oil company, make the transportation of the meat— and thereby the wild meat market itself—economically viable. Although sale of wild meat and products in Ecuador is illegal, the researchers report that "local authorities and park rangers know about the market, [but] they lack the resources and political will to stop the illegal trade of wildlife in Pompeya, primarily to avoid conflicts with the local indigenous population." Some communities of the Waorani tribe even abandoned their traditional semi-nomadic life and built settled villages along the http://print.news.mongabay.com/2009/0913-hance_ecuador_oil.html 20/05/2013 Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon - Pr... Page 2 of 3 road for easy transport of their game. They took up firearms (instead of the traditional blowguns), which became more prevalent following the arrival of the oil company. "These changes," the authors explain, "are amplified by patronizing relationships in which large companies buy their right to operate in the area by providing local communities with resources, money or Peccary legs. Wild meat fetched prices double that of domestic in the area. infrastructure without Photo by: Julie Larsen Maher © WCS. consideration of the social and ecological impact of these 'compensation plans'". The study published in Animal Conservation found that the wild meat market appeared shortly after the road was constructed in early 1990s and free travel was given to the indigenous tribes. Between 2005 and 2007, 11,000 kilograms (24,000 pounds) of wild meat were sold at the Pompeya market every year. The amount of meat sold every day doubled between 2005 and 2007, from 150 kilograms (330 pounds) to 300 kilograms (661 pounds). "While the magnitude of the wildlife trade occurring at Pompeya is still limited, its emergence and continuous growth are symptomatic of the dramatic changes that the area is experiencing under the influence of the oil industry and the absence of effective management and control strategies," the authors write. The most commonly targeted animals for the wild meat harvests were pacas, white-lipped peccaries, collared peccaries, and woolly monkeys. These four species made up 80 percent of the mammal, bird, and reptile meat collected, while fish, primarily caught by the Kichwa, tribe made up 30 percent of all the species' total. According to the researchers the availability of cheap travel for the tribes was the An oil truck on a barge in the Napo River near Yasuni National Park Photo largest factor in creating the by: Julie Larsen Maher © WCS. presence and size of the illegal market, while the demand for wild meat in restaurants spurred on the trade. Sixtynine percent of the meat was bought by middlemen—who consistently knocked-up the price around 60 percent. These middlemen then transported the meat to restaurants and markets as far away as 234 kilometers (145 miles). Consumers in the area were found to be willing to pay double for wild meat than what they would pay for domestic. "A simple, seemingly inoffensive road can have far-reaching effects on a landscape and its people," said Dr. Avecita Chicchón, Director of WCS’s Latin America and Caribbean Program. "It provides hunters with more access to a wider range of forest while providing a low-cost transportation route to markets. More importantly, it plugs communities more easily into the larger economic world while creating increased demand for numerous species of animals. It is the road to unsustainability." Citation: E.Suarez, M. Morales, R. Cueva, V. Utreras Bucheli, G. Zapata-Rios, E. Toral, J.Torres, W. Prado & J. Vargas Olalla. Oil industry, wild meat trade and roads: indirect effects http://print.news.mongabay.com/2009/0913-hance_ecuador_oil.html 20/05/2013 Indigenous groups oppose priest pushing for road through uncontacted tribes' land - Print Page 1 of 3 Please consider the environment before printing | PDF version Indigenous groups oppose priest pushing for road through uncontacted tribes' land Commentary by: David Hill, special to mongabay.com April 19, 2012 A view of Puerto Esperanza. Photo by: David Hill. A grassroots indigenous organization in Peru is calling for the removal of an Italian Catholic priest from the remote Amazon in response to his lobbying to build a highway through the country’s biggest national park. The park, in the Purus region in south-east Peru, was founded with the WWF’s support and is home to at least two groups of indigenous people living without any contact with outsiders, often called "uncontacted." The priest, Miguel Piovesan, has been vigorously promoting the highway in his parish magazine, on the parish radio and even during mass in the local church. The parish website features a photo of a sign reading, "WW, GET OUT OF PURUS NOW," "WW" being local short-hand for the WWF. But FECONAPU, an indigenous organization based in Purus's only town, Puerto Esperanza, is firmly against the road. It calls Piovesan’s lobbying a "disinformation campaign" and says he has "insulted," "mocked," "humiliated" and "defamed" Purus's indigenous residents opposed to his plans. "For years indigenous people in Purus have been the object of constant mockery and humiliation from the Catholic church’s representative, who has been obsessively trying to build a highway between Puerto Esperanza and Inapari," says FECONAPU, which represents 47 indigenous communities in Purus and claims the priest’s lobbying has created "marked ethnic tension" in the region. FECONAPU is now demanding Piovesan’s removal and is urging national indigenous organization AIDESEP to raise the matter with his superiors at the Apostolic Vicariate, which falls under the http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0419-hill_commentary_priest_peru.html 20/05/2013 Indigenous groups oppose priest pushing for road through uncontacted tribes' land - Print Page 2 of 3 immediate responsibility of the Vatican, in a town in Peru’s south-east. Piovesan, from Italy’s Veneto region, refused to comment, but a spokesman said the "uncontacted tribes 'made him laugh'." The priest has previously denied the existence of the tribes, leading one critic to describe him as "believing in the existence of God but not in indigenous people who live in voluntary isolation." FECONAPU is also calling for an investigation into Piovesan’s "real motives," and, according to AIDESEP, it has announced it will march in protest against him. "Purus’s indigenous population is against the highway," says FECONAPU’s Flora Rodriguez Arauso. "The people who want it are the priest and a few mestizos who actually live in Pucallpa." Piovesan argues the highway would bring "development," "freedom" and cheaper goods to Purus. At present, the region is so remote its only connection with the rest of Peru is by plane. But the director of the national park, Arsenio Calle Cordova, has dismissed these claims, saying the highway is about opening up the otherwise inaccessible forest to loggers in search of valuable timber. The Upper Amazon Conservancy, an American NGO working in the region, warns the highway could lead to "exponential increases in illicit resource extraction" including drug trafficking, mining and poaching as well as logging. Piovesan, who claims support from some local people, is fiercely critical of his opponents, both in Peru and abroad. In the latest edition of the parish magazine, Purus is described as "the property of polluting countries in the First World which, under a facade of 'protected areas,' are really protecting their own selfish, inhumane interests." "The majority of indigenous people in Purus, as well as local and even national authorities, believe the construction of this road would be extremely worrying," says Jorge Herrera from the WWF, which continues to support the national park’s protection. "It is not a road that would solve Purus’s isolation, but a strong government presence." If built, the highway would connect to the Inter-Oceanica road system running all the way from Brazil’s Atlantic coast to Peru’s Pacific. In addition to the national park, called by the WWF "a vast portion of the Amazon in its original state," the highway would cut through Purus’s Communal Reserve and a reserve for ‘uncontacted’ people in the Madre de Dios region. Piovesan’s position is in stark contrast to that adopted by other Catholic clergy in Peru in recent years. In a statement titled ‘The Catholic church’s role in the Peruvian Amazon’ made in 2010, the president of Peru’s Conference of Bishops committed his organization to promoting peace and warned against allowing powerful economic interests to exploit natural resources at the expense of others and the environment. "It’s reprehensible that a representative of God should adopt this kind of attitude," says ORAU, an indigenous organization, based in Pucallpa, to which FECONAPU is affiliated. "It’s an attitude that is far removed from his role as an evangelist and quite different from what is recommended by the Catholic church." Last month a delegation from Peru’s Foreign Relations Commission visited Purus to hold a public meeting and announced it would push for the highway’s construction in Congress. The meeting was condemned by FECONAPU, AIDESEP and the national park’s management committee, which complained many indigenous people could not attend or understand what was being said. Opposition to the highway centers on the impact it would have on local people, including the uncontacted groups, and the rainforest. http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0419-hill_commentary_priest_peru.html 20/05/2013 Indigenous groups oppose priest pushing for road through uncontacted tribes' land - Print Page 3 of 3 "It’s the largest protected area in the country and it now runs a serious risk of being invaded by a highway which threatens to destroy the lives of thousands of indigenous people by exposing them to the dangers of drugs trafficking, illegal logging, and unwanted contact," says AIDESEP. Some of the uncontacted people at risk are known as the ‘Mashco-Piro.’ Photos of a different ‘Mashco-Piro’ group made world headlines earlier this year after they were published by Survival International. "It’s an outrage that in the face of massive indigenous opposition plans for this road continue to push ahead," says Survival’s Rebecca Spooner. Comments (0) http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0419-hill_commentary_priest_peru.html Mongabay.com seeks to raise interest in and appreciation of wild lands and wildlife, while examining the impact of emerging trends in climate, technology, economics, and finance on conservation and development. Copyright mongabay 2009 http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0419-hill_commentary_priest_peru.html 20/05/2013 Industry-driven road-building to fuel Amazon deforestation Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com March 12, 2008 Unofficial road-building will be a major driver of deforestation and land-use change in the Amazon rainforest, according to an analysis published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Improved governance, as exemplified by the innovative MAP Initiative in the southwestern Amazon, could help reduce the future impact of roads, without diminishing economic prospects in the region. Roads in the Amazon Road-building spurs forest development in the Amazon by providing access for loggers, land speculators, ranchers, farmers, and colonists to otherwise remote wooded areas. Beyond facilitating deforestation, roads affect forests and biodiversity by fragmentation, which increases vulnerability to forest fires and has other negative ecological consequences. Still, roads are seen as an expedient way to expand extractive industries and promote agricultural expansion in the Amazon. As such, roads are increasingly funded and built by interest groups, especially the agroindustry and logging sectors. These "unofficial" roads complement existing government-sanctioned roads originally built under economic development schemes in the 1970s and 1980s. Industry also exerts pressure on lawmakers to fund road improvement projects, like the paving of highways. These improvements further promote the expansion of unofficial road networks, which improve the economic viability of resource extraction and agricultural production in once inaccessible areas. Improved economic viability provides greater incentive for more roadbuilding and the cycle continues. Reviewing the economic drivers of road-building in the Amazon, Stephen Perz and colleagues conclude that breaking the road-building feedback cycle will require improved governance. The authors cite the MAP Initiative in the southwestern Amazon as a model that could be used elsewhere in the Amazon to rein in and reduce the negative environmental impact of the unofficial roads, which are presently expanding at a significantly faster rate than official road networks in the region. Government road improvements spur expansion of unofficial roads The authors note that "distinguishing between official and unofficial roads in the Amazon reveals an important synergy: paving of official roads motivates unofficial road building." "Paving raises land values, which provides the incentive to exploit natural resources farther out from official road corridors. This in turn is made possible via construction or extension of unofficial roads, which then generate income that facilitates additional road building. This synergy poses a dilemma for environmental governance in the Amazon," they write. "On the one hand, official paving projects enjoy considerable political support and unofficial road building is crucial for local livelihoods. On the other hand, new infrastructure without environmental governance will probably lead to forest fragmentation and social conflicts. Such outcomes not only undermine the sustainability of current local livelihoods but also render forest more vulnerable to climate change, threatening future livelihood sustainability." Perz and colleagues say these issues have "prompted the discussion of new models of environmental governance" in the Amazon and cite the MAP Initiative as "an example of an innovative hybrid approach to environmental governance." MAP: A model for governance 'MAP' refers to the trinational frontier area between Bolivia, Brazil and Peru that is "incurring largescale infrastructure investments for the Inter-Oceanic Highway", a project that will connect Pacific Ocean ports to the heart of Amazonia with a paved highway. Projections for the region suggest the plan could have a detrimental impact on the environment: under a "business-as-usual" scenario, roughly 67 percent of MAP's 300,000 hectares of forest cover and 40 percent of its mammalian biodiversity will be lost by 2050. The authors say the MAP Initiative is working to avoid this fate by building capacity across national borders for tri-national environmental governance in what they call a "polycentric network". "The MAP Initiative has organized tri-national forums open to the public for presentations, dialogue and planning activities involving four key themes: economic development, environmental conservation, social equity and public policies," they write. "This multifaceted array of themes allows for consideration of the many impacts of roads as well as climate change." "The underlying strategy of the MAP Consortium is to premise trans-boundary environmental governance on sustaining an autonomous, polycentric structure that does not rely on a single centralized authority such as a government, or on a fully decentralized, uncoordinated network such as a set of local communities," they continue. "By retaining flexibility while ensuring coordination, the MAP Consortium constitutes a structure for collaborative environmental governance that can manage itself adaptively in order to respond quickly to rapid changes." Stephen Perz, a sociologist at the University of Florida, says the initiative — the planning process for which links scientific data to public deliberations involving industry, NGOs, local communities including indigenous groups, and state bodies — will help ensure proper governance no matter the future circumstances in the region. "The Inter-Oceanic Highway is bringing major changes to the southwestern Amazon, but it needs to be seen in the context of many other challenges, including other infrastructure projects, notably the Madeira Dam Complex, as well as climate change itself," Perz told mongabay.com via email. "The southwestern Amazon faces opportunities as well as perils due to economic integration -- such as growing investment from outside the Amazon in sugar cane and petroleum -- or from climate variability, which in recent years has included drought and fires (2005) as well as floods (2006 and right now in February 2008). This complex circumstance has strengthened recognition of shared interests and concerns among communities and local governments on all three sides of the MAP frontier. That has resulted in annual tri-national MAP [forums], open to the public, to broaden participation in planning for more sustainable resource management via a polycentric network." The same polycentric network concept could be applied in other parts of the Amazon where pressure from roads is likely to rise. The net effect: a reduction in deforestation, biodivesity loss, and conflict over land. Stephen Perz et al (2008). Road building, land use and climate change: prospects for environmental governance in the Amazon [FREE OPEN ACCESS]. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0026 Read more at http://news.mongabay.com/2008/0312-perz_amazon.html#CD4jMSaa7Tte615G.99 Ple as e c o ns id e r the e nviro nme nt b e fo re p rinting | PDF ve rs io n NGO: conf lict of int erest s behind Peruvian highway proposal in t he Amazon Jeremy Hance mongabay.com May 16, 2013 As Peru's legislature debates the merits of building the Purús highway through the Amaz on rainforest, a new report by Global Witness alleges that the project has been aggressively pushed by those with a financial stake in opening up the remote area to logging and mining. Roads built in the Amaz on lead to spikes in deforestation, mining, poaching and other extractive activities as remote areas become suddenly accessible. The road in question would cut through parts of the Peruvian Amaz on rich in biodiversity and home to indigenous tribes who have chosen to live in "voluntary isolation." If built, the Purús highway would run 270 kilometers (167 miles) from Puerto Esperanz a in Ucayali to Iñapari in Madre de Dios, bisecting Peru's Alto National Park, the Purús Community Reserve and the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve. According to the Global Witness report, the road would violate "Peru's laws on protected areas." However, the road has a number of influential supporters, including an Italian priest in the region, Miguel Piovesan, who first proposed the road's construction in 2004. Piovesan claims that those who oppose the road are denying economic development for local indigenous groups. In addition he says that isolated tribes do not exist in the area, despite evidence to the contrary from Peru's National Park service. But even the Global Witness report admits that the region is one of the most neglected in the country, likely due to a combination of remoteness and a very small population. PDFmyURL.com Aerial view of deforestation stemming from the controversial TransOceanic highway in the Peruvian Amazon. The major highway cuts through the rainforest in Brazil and Peru. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. "There is no doubt Purús needs development, according to the report. "73 percent of Purús homes do not have electricity and those which do only have access for five hours a day. A fifth of the population is illiterate, one of the highest rates in the country. There are only seven health posts and ten hospital beds in the whole province. Life expectancy and human development indicators are within the lowest 20 percent of all districts in Peru whilst per capita income is just US$85 a month." But Billy Kyte, campaigner with Global Witness, says that while no one disputes needs for development in parts of the region, the road is not the solution. "It is crucial that investment comes to the isolated Purús region to improve services for the population, but there are important questions to be answered over who this project would actually benefit. The huge social and environmental costs that would result from this new highway have not been properly assessed and Congress should vote it down," he notes. According to the report subsidiz ed and increased airfare could play a major role in alleviating poverty in the region without the road. PDFmyURL.com The report alleges that the build- up to the road project reaching the legislature has been marred by conflict- of- interests, illegal contracts for timber, discrimination against indigenous people, and even bribery. "A representative of the Federation of Native Communities of Purús Province (FECONAPU), the organiz ation representing Purús' indigenous communities, was offered a bribe of 30,000 Soles (around US$10,000) by a local government official to support the road construction," the report reads. Global Witness also says that Purús municipality had already begun logging the proposed road area, even though the project has not been improved. The NGO recommends that Peru's congress immediately suspend the highway bill and investigate possible conflict- of- interests connected to the legislation. Map of proposed highway. Image: Rocio Medina/La Republica. Image courtesy of Global Witness. PDFmyURL.com Innovative program seeks to safeguard Peruvian Amazon from impacts of Inter-Oceanic Highway - Print Page 1 of 7 Please consider the environment before printing | PDF version Innovative program seeks to safeguard Peruvian Amazon from impacts of Inter-Oceanic Highway By: Ryan King, special to mongabay.com March 06, 2012 An interview with Arbio Left bank: Arbio's concession area. Photo by: Arbio. Arbio was begun by Michel Saini and Tatiana Espinosa Q. in the Peruvian Amazon region of Madre de Dios. The project focuses on a protective response to the increased encroachment and destructive land use driven by development. The recent construction of the Inter-Oceanic Highway in the Madre de Dios area presents an enormous threat to forest biodiversity. Arbio provides opportunities to help establish a buffer zone near the road to limit intrusive agricultural and deforestation activities. Michel Saini is an Italian Environmental Engineer at the Polytechnic of Milan. In 2003 he traveled to Chile to study Forestry Engineering and learn what a real forest felt like. After this experience he decided to devote himself to the study and conservation of forests in Latin America. He moved to Costa Rica in 2007 and completed a Masters in Management and Conservation of Tropical Forests at CATIE, specializing in politics and governance of natural resources. In CATIE he meets a classmate, Tatiana Espinosa Q., Peruvian engineer in Forest Sciences at the UNALM, Peru. Her interest in the Amazon led her to work in the Madre de Dios region since 2003 on issues of Conservation, Wildlife and Management of non timber forest products. In 2009, after concluding the program, they traveled together to Madre de Dios and in 2010 Arbio was born. For more information, visit their website. INTERVIEW WITH ARBIO http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0306-king_arbio_interview.html 20/05/2013 Innovative program seeks to safeguard Peruvian Amazon from impacts of Inter-Oceanic Highway - Print Page 2 of 7 The Madre de Dios region is characterized by the world's highest diversity of butterflies. There are over 1200 species. Photo by: Arbio. Mongabay: What sorts of programs does Arbio plan to introduce in order to support local economies while avoiding the destruction of the forests and biodiversity in the Madre de Dios region? Arbio: We plan to introduce the concept of productive conservation, which is a concept of coexistence of society with the rainforest ecosystem. Our project includes the introduction of the Analog Forestry method, which is the exact opposite of a monoculture: Is a culture with 20 or more species in the same hectare, with different height and age and nutritional requirements. Fertilizers are no longer necessary, when we find the correlations between the nutrients needed and produced by each culture. This method seeks to maintain a functioning ecosystem dominated by trees while providing non-timber products (Brazil nuts, medicinal plants, Amazon fruits, etc.) and maintain a wildlife habitat. In this way, we seek to empower rural communities socially and economically through the use of species that provide commercial products. This system is completely integrated with the landscape, emphasizing the biodiversity to ensure sustainable production and operation is based on ecological considerations and ecosystem restoration. Mongabay: What are some of the most commonly seen animals in your area? Arbio: Among the mammals we have the mighty jaguar (Panthera onca), tapir (Tapirus terrestris), “sajinos” or wild pigs (Pecari tajacu), hundreds of herds of peccaries (Tayassu peccary). In the river can be seen the capybara - the largest rodent in the world (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), deer (Mazama sp), nocturnal animals such a chozna (Potos flavus), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), and a variety of monkeys including the howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus), white-fronted capuchin (Cebus albifrons), night monkeys (Aotus sp.), and tamarins (Saguinus sp.). Among the reptiles have the white caiman (Caiman crocodylus), the "taricaya" aquatic turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), tortoise (Geochelone denticulata), a variety of boas and snakes, lizards, etc. Among the birds we have the second largest species of the macaw (Ara chloropterus), the largest stork in South America: the Jabiru (Jabiru mycteria), toucans (Ramphastos cuvieri), the most http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0306-king_arbio_interview.html 20/05/2013 Innovative program seeks to safeguard Peruvian Amazon from impacts of Inter-Oceanic Highway - Print Page 3 of 7 powerful bird of prey: the Harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), also egret (Egretta thula), guan (Mitu tuberosum), pucacunga (Penelope jacquacu). In addition to a wide variety of arthropods such as butterflies (this region has the world record in butterfly species diversity), beetles, centipedes, spiders, ants that measure 4 cm, among others. Mongabay: Could you describe Arbio’s system of land rental of forested area by the hectare for conservation and research purposes? Arbio: Our project is funded entirely by individuals, through our web platform rentals. Any Internet user can choose their own hectare by seeing a satellite photo of each hectare of our base area and make a rental-for-conservation process which costs only US$42/year. Hectares chosen automatically come into the category of "absolute conservation" which means that only the local wildlife and our caretaker can enter, however, as the project progresses and the models of productive conservation will be implemented, we will connect by email the people who are protecting hectares in strategic locations (near the base camp or the trails) asking if they want to change their land’s use from absolute conservations to productive conservation. In short, the land use change possibility is only for strategic hectares and for those who want to give researchers the opportunity to test sustainable organic farming and/or medicinal plants following the model of the Analog Forestry, or to perform research related to the wildlife. Any details will be discussed with the tenant on a case by case basis. And if the tenant does not agree, the hectares will continue in absolute conservation, of course! Mongabay: What are some of the major threats posed by the construction of the Inter-Oceanic Highway? Arbio: The threat is historical and well documented. The same Inter-Oceanic Highway, in the Brazilian soil, led to deforestation of 50 Km of each side of the road in 20 years after his construction. If we don’t do anything, the same thing will happen in our region too, only at a faster rate, because everything is growing and getting http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0306-king_arbio_interview.html 20/05/2013 Innovative program seeks to safeguard Peruvian Amazon from impacts of Inter-Oceanic Highway - Print Page 4 of 7 faster in this endless-growth way of life. The threat is the actual system of what is seen as “development.” Extensive monoculture just doesn’t work for society or for the ecosystem. Very few people can work in extensive agriculture and fewer people really benefit from the immense fields. Deforestation is everywhere and fires and smoke can be seen from kilometers away. The Brazilian agro industry now can transport products directly to the Pacific coast avoiding a large trip from his Atlantic coast to the mayor markets: China and India. Additionally, the low price of land compared to Brazil, together with cost savings of Customs and the closer proximity to the Pacific will make the Peruvian Amazon the goal of the main industries of monocultures. Mongabay: Are conservation initiatives such as Arbio able to out-compete competition by extractive industries such as gold mining and monoculture plantations in the tropics? Concession area. Photo by: Arbio. Arbio: The answer to this question relies on the education of the actual land-owner and their capacity of long-term thinking. The current land tenure system in the Peruvian Amazon, a system of concessions granted by the state, is actually helping our job, even if some laws are against sustainability. Having the concession of a land for 40 years, renewable and heritable allow the tenants to think in long-term solutions for support themselves and their families, and selling the land or deforesting for monoculture is an absolutely short-term solution. They know that most of people that have sold his land are now living in the peripheries of the capital without a way of living, and the people who have transformed they land to a monoculture are now paying banks and fertilizers suppliers, with little or no benefit to their way of life. We offer for free a way of living close to their ancestral traditions but embedded in the actual market and granting sustainability in the future, not only with the Analog Forestry method of culture but also with the insertion in the Fair Trade Market and the future Payment for Environmental Services, when this opportunity will be available. Long-term thinking is our way to gain actual way of development. For more information, visit www.english.Arbioperu.org. http://print.news.mongabay.com/2012/0306-king_arbio_interview.html 20/05/2013 Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction - Print Page 1 of 6 Please consider the environment before printing | PDF version Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com September 24, 2009 Chainsaws, bulldozers, and fires are tools of rainforest destruction, but roads are enablers. Roads link markets to resources, enabling loggers, farmers, ranchers, miners, and land speculators to convert remote forests into economic opportunities. But the ecological cost is high: 95 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon occurs within 50-kilometers of a road, while in Central Africa, where logging roads are rapidly expanding across the Congo basin, the bulk of bushmeat hunting occurs near roads. In Laos and Sumatra, roads are opening last remnants of intact forests to logging, poaching, and plantation development. But roads also cause subtler impacts, fragmenting habitats, altering microclimates, creating highways for invasive species, blocking movement of wildlife, and claiming animals as roadkill. A new paper, published in Trends in Evolution and Ecology, reviews these and other impacts of roads on rainforests. Its conclusions don't bode well for the future of forests. Examining a large body of scientific literature, William F. Laurance, Miriam Goosem and Susan G.W. Laurance write that roads "can have an array of deleterious effects on tropical forests and their wildlife" in the form of biological and socioeconomic impacts. The latter is a far greater threat to forests. BR-230 highway near Rurópolis, Brazil in the heart of the Amazon. Image courtesy Over the past half of Google Earth century road networks have expanded across the tropics, opening remote forests to development. Once prompted primarily by political objectives such as national security, alleviating population pressures in cities, and rural development, roads are increasingly built by private interests — loggers, miners, and agribusiness — seeking access to resources and land. These "unofficial" roads complement existing government-sanctioned roads, amplifying their already substantial impact. Industry also exerts pressure on lawmakers to fund road improvement projects, like the paving of highways. These improvements further promote the expansion of unofficial road networks, which improve the economic viability of resource extraction and agricultural production in once inaccessible areas, attracting colonists and speculators, who cut and burn forests, hunt, and introduce alien species. Improved economic viability provides greater incentive for more road-building and the cycle continues. Roads in the Amazon The Brazilian Amazon is prime example of how roads have spurred large-scale change in the rainforest. Extensive deforestation began in the late 1960s when the Brazil's military government launched development programs to promote colonization in the region. The plan, which sought to provide economic opportunities for landless poor from crowded parts of the country and establish a national presence in the vast and sparsely populate interior, offered subsidized loans to settlers and ranchers, and funded ambitious highway projects like the Trans-Amazonian highway. http://print.news.mongabay.com/2009/0924-roads.html 20/05/2013 Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction - Print Page 2 of 6 While the TransAmazonian largely failed to meet its economic and social goals, it did open up large tracts of previously inaccessible rainforest land to development. Vast stretches of land were cleared for lowintensity cattle pasture and shortterm subsistence agriculture. Despite laws restricting landclearing to 50 percent of a settler's holdings, deforestation rates climbed from negligible to more than 20,000 square kilometers per year in the 1980s. Giant infrastructure projects—notably dams—facilitated development in the region, while logging spurred the growth of unofficial road networks and subsidized agricultural expansion that has Forest clearing and development near Tailândia, Brazil. Image courtesy of Google helped turn Brazil into Earth the world's largest exporter of many farm products. Its emergence as a global agricultural superpower has today created in Brazil a strong political block that lobbies for new infrastructure developments in the Amazon. With tens of billions of dollars now allocated to projects, including improvement of existing roads and construction of new highways, the future of the Amazon is increasingly linked to globalized markets, including demand for commodities. But road impacts in the Amazon are not limited to Brazil. Peru is putting the finishing touches on the Carretera Transoceanica, a highway that will connect the heart of the Amazon to Pacific ports. The project, which is largely funded by China and Brazil, will create an export pipeline for timber, minerals, and agricultural products to the world's fasting-growing consumer. Oil, gas, and mining companies are already setting up shop in the area, sometimes in conflict with indigenous groups and protected areas. Meanwhile roads are also extending into key forest areas in Guyana, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and other parts of Peru. Outside of Latin America, major roads projects are planned or under construction in a number of tropical forests areas. Among others, the authors note the Trans-Congo Road in Democratic Republic of Congo, a 1600-km road that will cut southeast to northwest across the Congo Basin providing access to timber and minerals; the North–South Economic Corridor, a 1500-km highway across Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar; the Leuser Road Plan, a network of more than 1600 km of major and minor roads in northern Sumatra; and the Mamberamo Basin Road which will run 1400 km through primary rainforests in northwestern New Guinea (Indonesia). Limiting damage from roads Aside from restricting development of new roads from frontier forest areas, there are limited options for mitigating the impacts of road expansion. Current efforts focus on measures taken in advance of road construction. For example, the Juma Sustainable Development Reserve Project for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Deforestation aims to curb forest clearing along the AM-174 and BR-319 highways by establishing a network of strict http://print.news.mongabay.com/2009/0924-roads.html 20/05/2013 Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction - Print Page 3 of 6 protected areas along the roads. The project is financed by a forest carbon fund on the basis that it will reduce emissions from deforestation by 190 million tons of carbon dioxide by 2050 compared to a business-as-usual approach. The authors also highlight other mechanisms for minimizing road impacts, including regulating access to roads, promoting railroads when possible, requiring proper environmental impact assessments prior to construction, limiting road width and gradient, restricting tree clearing along roads, and banning night-time driving. But in the end, the authors conclude that "actively limiting frontier roads... is by far the most realistic, cost-effective approach to promote the conservation of tropical nature and its crucial ecosystem services." Roads in the Brazilian Amazon. Courtesy of Digital Earth. William F. Laurance, Miriam Goosem and Susan G.W. Laurance. Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Trends in Evolution and Ecology (TREE) 1149 1–11 Comments (0) Related articles Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon (09/13/2009) The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador's Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call "one of the most species diverse forests in the world"—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest. New legislation in Brazil opens up road-paving across country, threatening Amazon (04/21/2009) Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies has approved a measure that would speed up paving roads across the country, including paving a road that environmentalists have longfought, BR-319. Environmental groups across the nation have warned of widespread deforestation if the measure passes the Senate and is signed by the president. Reserves with roads still vital for reducing fires in Brazilian Amazon (04/08/2009) Analyzing ten years of data from on fires in the Brazilian Amazon, researchers found that roads built through reserves do not largely hamper a reserve's important role in reducing the spread of forest fires. The finding is important as Brazil continues a spree of road-building while at the same time paving over existing roads. http://print.news.mongabay.com/2009/0924-roads.html 20/05/2013 Logging roads rapidly expanding in Congo rainforest mongabay.com June 7, 2007 Logging roads are rapidly expanding in the Congo rainforest, report researchers who have constructed the first satellitebased maps of road construction in Central Africa. The authors say the work will help conservation agencies, governments, and scientists better understand how the expansion of logging is impacting the forest, its inhabitants, and global climate. Analyzing Landsat satellite images of 4 million square miles of Central African rainforest acquired between 1976 and 2003, a team of researchers led by Dr. Nadine Laporte of the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) mapped nearly 52,000 km of logging roads in the forests of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Republic of Congo, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). They found that road density has increased dramatically since the 1970s and that around 29 percent of the remaining Congo rainforest was "likely to have increased wildlife hunting pressure because of easier access and local market opportunities" offered by new logging towns and roads. "Roads provide access, and this research provides clear evidence that the rainforests of Central Africa are not as remote as they once were .a bad thing for many of the species that call it home," said Jared Stabach, a researcher at WHRC and a coauthor of the paper. Roads appearing fastest in Republic of Congo, but DRC is next frontier The authors report that the highest logging road densities were in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, while the most rapidly changing area was in northern Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), where the rate of road construction more than quadrupled--from 156 kilometers per year to over 660 kilometers--between 1976 and 2003. The scientists found evidence of new frontier of logging expansion in DRC, which has just emerged from nearly a decade of civil war. "It has never been timelier to monitor forest degradation in Central Africa because there is still Logging road density in Congo countries. an opportunity to make a significant difference in reducing the amount of deforestation. The Democratic Republic of Congo contains most of the remaining forest and is the last frontier for logging expansion in Africa," said Laporte. Selective cutting still damaging; certification offers hope The authors note that more than 600,000 square kilometers of forest are presently under logging concessions, while just 12% of the area is protected. Most logging in the area is focused on selective harvesting of high-value tree species, like African mahoganies, for export, rather than clear-cutting. Monitoring the expansion of logging in last dense humid forest of Central Africa is not only important for biodiversity conservation but also for climatic change. Industrial logging in Central Africa is the most extensive land use with more than 30 percent of the forest under logging concession and the clearing of these forests could significantly increase carbon emissions. -Woods Hole Research Center Laporte says that selective cutting is increasingly driven by demand from European firms for certified timber, a trend that could eventually slow forest loss and degradation in Central Africa. "In central Africa, Reduced Impact Logging (RIL) has been adopted by many companies during the past 5 years under the pressure of European markets for certified wood," Laporte told mongabay.com. "It has definitely improved logging operations of large European logging companies; most of them have now adopted forest management plans, though small companies are still behind, struggling with the associated costs... [and] maybe just lack of interest, since they can sell noncertified wood to Asia and other countries that do not care much about certification." "I think that the future of many tropical forests is linked to our success of making people in Asia and elsewhere supportive of certification," she continued. "Education is key, and the media can play an important role. The info is there, but we need to reach the big consumers." Logging and the bushmeat trade A number of studies have linked logging roads to the bushmeat trade. In April, Science reported higher incidence of elephant poaching in close proximity to logging roads, while a May 2006 Conservation Biology study showed that roads and associated hunting pressure reduced the abundance of a number of mammal species including duikers, forest elephants, buffalo, red river hogs, lowland gorillas, and carnivores in the tropical forests of Gabon. Commercial hunting to meet market demand in cities and overseas is a greater threat than subsistence hunting. Laporte says that simple rules can reduce impact of logging roads on wildlife including: closing the logging road to traffic following the timber harvesting; establishing checkpoints to look for illegal bushmeat or ivory; banning logging roads near protected areas; and providing alternative sources of protein (such as fish ponds) to workers in logging camps. Broader implications of the logging road study Laporte and colleagues say the study will help policymakers and scientists better assess logging expansion in Central Africa as well as the potential impact of logging on global warming emissions. "Africa is poised for irreversible change, so it is important to help African countries with tools to monitor what is happening to their forests." said co-author Scott Goetz, a senior scientist at WHRC. "This work helps to provide key data to local scientists, allowing them the tools needed to work with policy makers to help manage their forests, and in the process reduce biodiversity loss and carbon emissions from deforestation," added Laporte. CITATION: Nadine T. Laporte, Jared A. Stabach, Robert Grosch, Tiffany S. Lin, Scott J. Goetz (2007). Expansion of Industrial Logging in Central Africa. Science 8 June 2007. Ayous loggers in Congo. Photo by Nadine Laporte. Toll road could raise money for Amazon conservation mongabay.com July 15, 2007 Southeastern Peru is arguably the most biodiverse place on the planet. A new highway project, already under construction, poses a great threat to this biological richness as well as indigenous groups that live in the region. While its too late to stop the road, called the Carretera Transoceanica or Interoceanic Highway, there are ways to reduce its impact on the forest ecosystem and its inhabitants. A new proposal, backed by a group of well-respected researchers, argues that turning parts of the highway into a toll road could help pay for conservation efforts that will mitigate damage to the surrounding rainforest. Organizers are asking supports to sign a petition that will then be presented to the Peruvian president. A statement from the group appears below. Highway up - A solution to unite economic development and conservation within the Andes-Amazon Region The Interoceanic Highway is currently under construction in South America. It is predicted to result in unprecedented destruction of the Amazon — the largest tropical forest in the world. In southern Peru the highway will slice through the Andes-Amazon region, critical habitat of the highly threatened Andean Bear, as well as jaguars, giant otters, and more than 1,200 other species of mammals and birds. Once the highway is complete, the A so-called Giant monkey frog from the threatened region in Peru. Photo by Rhett wilderness these species inhabit A. Butler today will be forever cut in two, separated by a growing corridor of deforestation along the highway. Elevating critical portions of the Interoceanic Highway, turning it into a toll pay scenic road, will help the conservation of the Andes-Amazon region and at the same time will catalyze the long-term economic stability of local people through ecotourism. Limiting economic activities around the highway only to special exits can be a great opportunity for regional economic growth. Doing so will reduce habitat destruction by restricting uncontrolled development of land away from the specified exits. At the same time it will be possible to offer tourists a variety of needs at one stop, including hotels, restaurants and field guides ready to show tourists the unique regional fauna and flora that should be regarded with pride and protected accordingly.