Renu Journal 2013 Final - Uttarakhand State Ophthalmological

advertisement

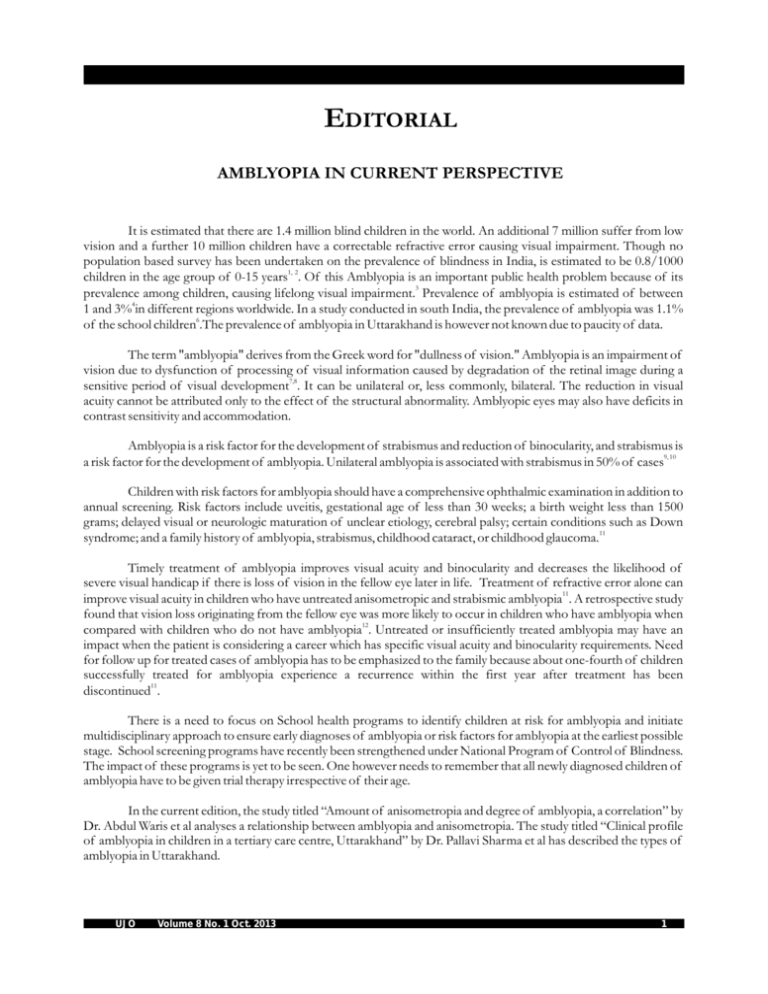

EDITORIAL AMBLYOPIA IN CURRENT PERSPECTIVE It is estimated that there are 1.4 million blind children in the world. An additional 7 million suffer from low vision and a further 10 million children have a correctable refractive error causing visual impairment. Though no population based survey has been undertaken on the prevalence of blindness in India, is estimated to be 0.8/1000 1, 2 children in the age group of 0-15 years . Of this Amblyopia is an important public health problem because of its prevalence among children, causing lifelong visual impairment.3 Prevalence of amblyopia is estimated of between 1 and 3%4in different regions worldwide. In a study conducted in south India, the prevalence of amblyopia was 1.1% 6 of the school children .The prevalence of amblyopia in Uttarakhand is however not known due to paucity of data. The term "amblyopia" derives from the Greek word for "dullness of vision." Amblyopia is an impairment of vision due to dysfunction of processing of visual information caused by degradation of the retinal image during a sensitive period of visual development7,8. It can be unilateral or, less commonly, bilateral. The reduction in visual acuity cannot be attributed only to the effect of the structural abnormality. Amblyopic eyes may also have deficits in contrast sensitivity and accommodation. Amblyopia is a risk factor for the development of strabismus and reduction of binocularity, and strabismus is 9, 10 a risk factor for the development of amblyopia. Unilateral amblyopia is associated with strabismus in 50% of cases Children with risk factors for amblyopia should have a comprehensive ophthalmic examination in addition to annual screening. Risk factors include uveitis, gestational age of less than 30 weeks; a birth weight less than 1500 grams; delayed visual or neurologic maturation of unclear etiology, cerebral palsy; certain conditions such as Down syndrome; and a family history of amblyopia, strabismus, childhood cataract, or childhood glaucoma.11 Timely treatment of amblyopia improves visual acuity and binocularity and decreases the likelihood of severe visual handicap if there is loss of vision in the fellow eye later in life. Treatment of refractive error alone can 11 improve visual acuity in children who have untreated anisometropic and strabismic amblyopia . A retrospective study found that vision loss originating from the fellow eye was more likely to occur in children who have amblyopia when 12 compared with children who do not have amblyopia . Untreated or insufficiently treated amblyopia may have an impact when the patient is considering a career which has specific visual acuity and binocularity requirements. Need for follow up for treated cases of amblyopia has to be emphasized to the family because about one-fourth of children successfully treated for amblyopia experience a recurrence within the first year after treatment has been discontinued11. There is a need to focus on School health programs to identify children at risk for amblyopia and initiate multidisciplinary approach to ensure early diagnoses of amblyopia or risk factors for amblyopia at the earliest possible stage. School screening programs have recently been strengthened under National Program of Control of Blindness. The impact of these programs is yet to be seen. One however needs to remember that all newly diagnosed children of amblyopia have to be given trial therapy irrespective of their age. In the current edition, the study titled “Amount of anisometropia and degree of amblyopia, a correlation” by Dr. Abdul Waris et al analyses a relationship between amblyopia and anisometropia. The study titled “Clinical profile of amblyopia in children in a tertiary care centre, Uttarakhand” by Dr. Pallavi Sharma et al has described the types of amblyopia in Uttarakhand. UJO Volume 8 No. 1 Oct. 2013 1 REFERENCES 1. A Study on Childhood Blindness, Visual Impairment and Refractive Errors in East Delhi. New Delhi: Community Ophthalmology Section, RP Centre, AIIMS; 2001. 2. Community Based Screening of Children for Detection of Visual Impairment in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Blindness Control Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi; 2006. 3. Hillis A, Flynn JT, Hawkins BS. The evolving concept of amblyopia: a challenge to epidemiologists. Am J Epidemiol 1983;118:192-205. 4. Bruce A, Pacey IE, Bradbury JA, Scally AJ, Barrett BT. Bilateral Changes in Foveal Structure in Individuals with Amblyopia. Ophthalmology. Sep 29 2012;[Medline]. 5. Von Noorden GK. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management. 1996;216-54. 6. Ganekal S, Jhanji V, Liang Y, Dorairaj S. Prevalence and etiology of amblyopia in Southern India: results from screening of school children aged 5-15 years.Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013 Aug;20(4):228-31. 7. Kushner, BJ. Amblyopia. In: Nelson LB, ed. Harley's Pediatric Ophthalmology. 1998:125-39. 8. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Amblyopia. In: Basic and Clinical Science Course: Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1997: 259-65 9. National Society to Prevent Blindness. Vision problems in the U.S. Data analysis. Definitions, data sources, detailed data tables, analysis, interpretation. Publication P-10. New York: National Society to Prevent Blindness, 1980. 10. National Advisory Eye Council. Vision Research: A National Plan. Report of the Strabismus, Amblyopia, and Visual Processing Panel, Vol 2, Part 5. Bethesda: US DHHS, NIH Publ No. 83-2475, 2001. 11. American Academy of Ophthalmology Pediatric Ophthalmology /Strabismus Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. Amblyopia. San Francisco, CA. American Academy of Ophthalmology;2012 12. Tommila V, Tarkkanen A. Incidence of loss of vision in the healthy eye in amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol 1981;65:575-7. Dr. Renu Dhasmana Editor UJO Volume 8 No. 1 Oct. 2013 2

![INITIAL ENTRY [headstart - fourth (4) grade]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007186926_1-bbcbbac65c6b7e51aa650c936c0e7792-300x300.png)