Perceived Barriers to Parental Involvement in Schools - UW

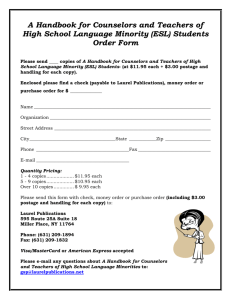

advertisement

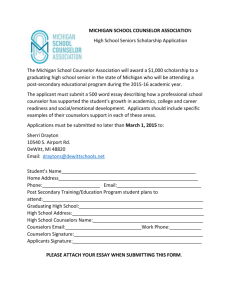

1 Perceived Barriers to Parental Involvement in Schools by Lindsay J. Horvatin A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree In School Counseling Approved: 2 Semester Credits The Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout December, 2011 2 The Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout Menomonie, WI Author: Horvatin, Lindsay J. Title: Perceived Barriers to Parent Involvement in Schools Graduate Degree! Major: MS School Counseling Research Adviser: Carol Johnson, Ph.D. MonthN ear: December, 2011 Number of Pages: 42 Style Manual Used: American Psychological Association, 6th edition Abstract While many parents make good effort to attend school functions and support the educators who work with their children, some parents perceive barriers to participation in schoolrelated activities. Literature indicated perceived language barriers, cultural understanding conflicts, financial and work related restraints, an atmosphere that is not always welcoming, judgmental attitudes, inconvenient scheduling, and lack of resources in time and money. Parents who are involved in their children's education tend to having higher expectations, encourage children to participate in activities, and notice higher performance in academics in the school setting. Educators who are aware of the perceived barriers can do much to help parents who are not involved with the school. School administrators or counselors who provide training to staff encouraging a welcoming environment and multiple opportunities to connect with parents in a positive manner, notice that parent engagement increases. School counselors, administrators and 3 other educators need to be knowledgeable about how perceived barriers regarding participation in school settings impacts children at school. Educators need to utilize interventions and strategies to help children succeed while promoting parent involvement by removing perceived barriers encountered by dysfunctional or disadvantaged families. 4 The Graduate School University of Wisconsin Stout Menomonie, WI Acknowledgments I would like to thank my husband, parents, and sister for their overwhelming support as I have not only finished my thesis, but also my graduate degree. My husband, Josh, was willing to work while I went back to school and went above and beyond to help out so it was possible for me to get things done. He has always helped me to see the big picture and what I am working toward. My parents, Steve and Barb, and sister Ashley have also been incredibly supportive as when I needed encouragement or help, they were always there and went out of their way to make things easier for me. Their kind words and motivational support were always helpful to me and I know that my success in completing my thesis and graduate school would not have been possible without these people and I am incredibly grateful to them. I would also like to thank my graduate school and research advisor Dr. Carol Johnson for all her help, support and advice. She has a positive and upbeat attitude that has helped me to believe I can do this and be successful. Throughout the program and while working on my thesis, her support and assistance made it possible for me to be successful and I am so blessed to have had the opportunity to work with her. 5 Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... Page Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter I: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 6 Statement of the Problem ................................................................................................. 8 Purpose of the Study ........................................................................................................ 8 Research Questions .................................................................................. 8 Assumptions and Limitations of the Study ....................................................................... 9 Definition of Terms ....................................................................................................... 10 Chapter II: Literature Review .................................................................................................... 12 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 12 Perceived Barriers to School Involvement ..................................................................... 12 Challenges for Parents ................................................................................................... 16 Not Always a Welcome Environment ............................................................................ 17 Strategies to Increase Parent Involvement ...................................................... 20 Making Time in a Busy Schedule ................................................................. 29 Research Models that Support Parent Involvement. ........................................... 30 Chapter III: Summary, Discussion and Recommendations ........................................................ 35 Summary ....................................................................................................................... 35 Discussion ..................................................................................................................... 37 Recommendations ......................................................................................................... 38 References ................................................................................................................................ 40 6 Chapter I: Introduction Nearly all individuals experience belonging to and interacting with a type of family system at some point during their lifetime. While most children enjoy childhood and spending time with their families, some find childhood to be filled with turmoil and challenges. Family dysfunction for this paper is defined using Webster's Dictionary as impaired, abnormal or unhealthy interactions or interpersonal behavior (http://www.merriamwebster.comldictionary/ dysfunction) and therefore, dysfunctional families as those families in which caregivers are unable to consistently fulfill family responsibility (http://medicaldictionary. thefreedictionary .comlFamily+dysfunction). Those families who experience dysfunction, may do so on varying levels of intensity. For some, dysfunction may be mild and seen as normal day-to-day functioning, while others experience more severe and detrimental challenges that threaten the family system and the success of those in it. In these types of situations, children may be physically or emotionally scarred from physical or emotional violence that affects them not only at home, but may also carryover in other areas such as school, work, or in the development of healthy relationships of their own in the future. Dysfunction may also put children at risk for increased negative school experiences, and emotional, physiological, and social consequences (Lambie & Sias, 2005). There are countless types of challenges that families face today, and discussing each and every type would be beyond of the scope of this study. For some, dysfunction could be how the family or children live day to day, such as with one parent, in a foster horne, constantly moving, with a parent in prison, a parent deployed in the military, or perhaps a chaotic family structure of many step and half siblings that can be very confusing to the child. Some families may identify grief as disruptive to the family structure as grief may come with a sudden loss, a divorce or 7 death of someone in the family battling an illness, such as cancer or even a mental illness or severe addiction. Dysfunction could also be characterized by how the family interacts or how the children are nurtured. In some families, parents may be dependent on drugs or alcohol, and children may be unsupervised or even neglected or abused. With so many potential types of dysfunction, poverty is also perceived as a type of family dysfunction as it may put them at a disadvantage. In the current economy, poverty affects many families and appears to be on the rise. In 2009 the poverty rate was 14.3%, which was an increase from 13.2 % in 2008 (Poverty in the United States, 2010). It should also be noted that poverty is often defined as a lack of income, but poverty may also result in the lack of power, humiliation, and a sense of being excluded by others (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Living in poverty, many families find they are often unable to support their children or parent their children as they would like, and poverty could further have an impact on student achievement. Therefore, there is a need for educators and school counselors to be knowledgeable about how poverty impacts children at school and to utilize interventions and strategies to help children succeed while promoting parent involvement by removing perceived barriers encountered by dysfunctional and disadvantaged families. Children living in poverty are at risk for experiencing education hardships such as grade retention, dropping out, and being referred for special education classes (Benner & Mistry, 2007). However, it should be noted that not all children living in poverty are destined to fail. Benner and Mistry (2007) stated that 50% of children living in poverty will obtain their diploma or an equivalent, and of those who graduate, 53% will continue their education and attend college. School counselors need to be ready to intervene and get parents involved early in their children's schooling, so that more of these children living in poverty or dysfunctional homes 8 would graduate and pursue additional education and training. School counselors often have opportunities to connect with all families, the offer to assist them, and direct them to needed resources (Lambie & Sias, 2005). Counselors could playa role in improving the education for those children living in poverty. Statement of the Problem With the increase in immigration and language barriers, the challenges faced by families in the current economy who are working multiple jobs to keep the family together, parents are indicating perceived barriers to becoming involved in their children's education. Seeking ways to identify and remove barriers to help all children find success is important to educators. The problem becomes, what barriers are parents experiencing and what strategies are available to help these families overcome the obstacles to parental involvement? Purpose of the Study The purpose of this literature review is to examine the impact of dysfunctional and disadvantaged families on student achievement. In addition, strategies that school counselors could utilize to help these students and encouraged parental school involvement will be collected through a comprehensive literature review during the fall semester of 20 11. Research Questions The following research questions will be addressed throughout this literature review: 1. How does dysfunction and disadvantage impact the academic achievement of students? 2. How does parental involvement impact students' academic achievement? 9 3. What types of strategies could be utilized to assist children living in poverty or dysfunctional homes, and how can educators encourage parents to become more involved in their children's schooling? Assumptions and Limitations of the Study Dysfunction could be defined in a number of ways, but for this paper it is a family who struggles with an identity and unclear role expectations. It is assumed that poverty may add to the dysfunction of the family as members take on multiple roles such as older children become the caregiver to younger children, parents may be absent due to working multiple jobs and children may be subject to large amounts of unsupervised time. When this carries over in to the schools, children may not be prepared for school, may stay up too late, may also be working to contribute to the family, and may have stress and fatigue that keep them from performing well at school. It is also assumed that parents are willing to become more involved in their children's lives and in their education. While not all parents are able to be involved, if perceived barriers including feeling welcome, adjusting meetings to meet their schedules, adoption of materials in their language, and a non-judgmental attitude, parents may be willing to meet educators half way. The final assumption is that "parents" is applicable to many different types of parental figures, such as grandparents, step-parents, adopted parents, or parents who serve as the legal guardians of children. Therefore, throughout this study "parents" will be used to refer to the wide array of parental figures that may be present in children's lives. 10 One limitation to this review of literature is the number of sources available at the time of writing. Some materials may have been overlooked or omitted due to time restraints and limited resources ofthe writer. Another limitation is that school counselors have limited time and resources to intervene and assist families by offering support, meeting with parents and students and directing them to outside resources. Improvements in parental involvement may only occur if parents are willing to try interventions or strategies offered to them as school leaders are only able to help to a certain extent before parents must take the initiative to make the next step. Definitions of Terms American School Counseling Association (ASCA). The agency that developed the national model and standards for school counselors to help identify and prioritize the skills, knowledge and attitudes that students should acquire from being involved with a school counseling program. (American School Counselor Association, 2011). Dysfunctional family. Dysfunction is defined as impaired, abnormal or unhealthy interactions or interpersonal behavior in families in which caregivers are unable to consistently fulfill family responsibility (www.merriam-webster.com!dictionaryI dysfunction) (http://medicaldictionary .thefreedictionary. com!F amily+dysfunction). Funds of knowledge. Funds of knowledge are the values, skills, and knowledge that families have acquired or built, and the focal point from which the family may perceive things and learn (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). No Child Left Behind (NCLB). This act was signed into law in 2002 as a way to reform education. The main goal ofNCLB is to close the achievement gap between minority and disadvantaged K-12 students (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2011). 11 Poverty. Includes those individuals who struggle to obtain adequate shelter, food and basic needs that are required for daily living (Russel, Harris, & Gockel, 2008). 12 Chapter II: Literature Review Introduction This chapter includes a comprehensive literature review that begins by looking at types of family dysfunction and the limiting impacts that poverty may have on children's achievement in school. The literature reviewed indicated techniques or strategies that could be utilized by schools counselors, to assist children living in poverty and to engage their families in becoming more aware of potential resources. The chapter concludes with ways to identify and remove perceived barriers, so that parents may become more involved with the school. Perceived Barriers to School Involvement Living in poverty can be difficult and challenging not only for children, but also for parents. There seems to be a lack of research on how school counselors can assist low-income students, and as Amatea and West-Olatunji (2007) further stated, fewer than ten articles seem to discuss the efforts of school counselors in combination with poverty and social class over the last decade. There appear to be many benefits of parents staying involved with their children's education, but parents living in poverty are less likely to participate with school events or their children's education than those living out of poverty (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). Some parents may willingly not participate, or have no wish to be involved, while others may want to be involved, but unable. For example, take a family struggling to make ends meet. One or both parents may have to work long hours at one or more jobs, with an inconsistent and irregular schedule that makes it difficult for them to find time to be involved. In their free time, these parents may need to catch up on sleep, run errands, pay bills, or care for small children or others at home such as elderly parents (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). If money is tight, parents may not have the funds to be 13 involved in certain school functions or may not be able to afford the gas or transportation to get to and from the school. It often costs additional money to purchase equipment to participate in sports, such as soccer shoes, team uniforms, mouth guards, special insurance or summer camps. If parents have limited resources, it may limit opportunities for students to participate in extracurricular activities. Parents may miss out on car-pool opportunities and chances to meet and connect with other parents who could provide encouragement and emotional support to the family. If school personnel don't know about the parent's financial limitations, they are often unable to offer scholarship for extra-curricular activities or waive fees for the family. Due to their upbringing and possible lack of education, some parents living in poverty may doubt their abilities and feel because they did not obtain a certain level of education when they attended school, that they are not suited to assist their children with their academics (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). Due to these inferior feelings, parents may refrain from becoming involved with the school, athletic events, or helping their children with schoolwork at home. Still other parents may have a sense of pride and may not want to ask for a hand-out. They keep their personal business and finances to themselves and do not wish to disclose to others their limited budgets that may present as a barrier to becoming more involved in school. Those living in poverty are often at a greater risk for mental health diagnosis, and unfortunately, also have limited access to mental health services (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Depression is often linked with poverty which not only may put children at risk, but also parents who may be dealing with their own mental health issues and unable to exert a great deal of energy into their children's education (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). In addition to depression and lower participation at school, children living in poverty are at an increased risk to have anxiety and behavioral difficulties. Once in school, children living in poverty may fail, develop 14 educational delays, not graduate, may have lower standardized test scores, higher incidences of tardiness and absenteeism, and dropping out of school than their peers who are not from lowincome families (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Not only are children living in poverty at risk for development of depression, anxiety, and distress, but adolescents in general are at an increased risk because of the emotional, physical, and intellectual changes they are going through as they are developing (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). Once children mingle with others, they tend to notice the "have and have not" in the cars kids drive to school, in the homes they live in, the electronic gadgets they carry, vacations they experience, and in the clothes they wear. Some students may feel embarrassed to have hand-medowns or second-hand clothes, distressed cars, low-income housing and limited gadgets to entertain themselves. This may create a feeling of inferiority. They could be embarrassed to have their families come to school. Therefore, adolescents living in poverty are at an even higher risk of struggling in school (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). Children living in poverty are not only at risk for mental health disorders, but also abuse, neglect, and deviant behaviors such as increased incidences of violent crimes, drug use, and pregnancy (Bennett-Johnson, 2004; Russel, Harris, & Gockel, 2008). As described earlier, families living in poverty may be chaotic, dysfunctional, and even lack support for one another. Parents may not be present as much as needed to parent their children appropriately. Parents may also have lower expectations for their children, and be poor role-models, exposing their children to some of their own poor habits, such as drug use (Bennett-Johnson, 2004). Children living with parents who use and abuse drugs or alcohol are not only being exposed to an environment of drug use, but also may struggle at school. It was estimated that 15 15% of children under the age of 18 years old were living with at least one person diagnosed or dependent on alcohol in the last year (Lambie & Sias, 2005). Lambie and Sias (2005) stated that these children often go unidentified at school, putting them at risk for lower academic achievement and delinquent behaviors. Living in an environment in which a parent abuses alcohol can be very chaotic and it may be difficult for children to get appropriate rest or help from parents; therefore, children may be unable to finish their homework, putting them at even greater risk. Lambie and Sias (2005) further went on to say that parents who abuse alcohol may seem uninterested in their children's education to school staff. They may be hard to reach, may not keep appointments, and sometimes even show up to school under the influence of alcohol. In addition to risks at home, children with alcoholic parents may show delinquent behaviors sooner than their peers, be at risk for academic failure, involved with gangs, and lack commitment to school. It is not implied that all parents living in poverty use or abuse drugs and alcohol, but those parents who do, may have additional factors to contend with in addition to those already present for families living in poverty, which may prevent them from being involved with the school and their children's education (Bennett-Johnson, 2004). When parents are uninvolved in their children's education, make poor decisions, have irregular employment or are unemployed, the children are also impacted as the parents are modeling these behavior patterns to their children, who are likely to see their parents as role models (Bennett-Johnson, 2004). This is why intervention at any level, such as a school counselor trying to help parents become more active in their children's education, may not only be beneficial for children at the time, but for their future children as well, who are likely to develop the same behavior patterns if nothing changes. Not only are children's future behaviors 16 influenced by modeling from their parents, but student success in school can actually be impacted by parental involvement in school. Other parents may not speak fluent English and find it difficult to be involved with school activities or volunteer opportunities due to the language barrier. In addition to the language barrier, some parents' cultures encourage them not be become too involved in school and feel to do so is disrespectful (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). There may be cultural issues that conflict with dress code restrictions. Cultural issues may also prevent families from participating in holiday activities based on family values and beliefs. At times, there may be parents who perceive the school as an intimidating environment and feel that they are discriminated against by school staff, therefore keeping their distance from the school. Parent involvement is thought to be a powerful predicator of academic achievement, along with a sense of well-being, school attendance, grades, and aspirations for the future (Benner & Mistry, 2007; Holcomb-McCoy, 2010). In a meta-analysis of studies, Van Velsor and Orozco (2007) showed a significant relationship between the academic achievement of children and parental involvement in school. Despite the benefits of parental involvement in school, lowincome parents participate much less than their counterparts who are not from a low-income status (Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007). Challenges for Parents If research indicates that children do better in school when parents are involved, then what prevents parents from becoming involved in school? The answer to this question is not an easy one, as parents themselves may be unsure of what is preventing them from being involved or may not give school staff an accurate perception of why they choose not be involved. Perhaps, as discussed above, parents really do want to be involved, but just are unable to do so. 17 Some parents, especially those living in poverty, may have long, frequent, and unpredictable work hours and multiple responsibilities at home that prevent them from being involved as much as they would like. In many cases, school activities or events are held at times that are convenient for the school and not always convenient for the families (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). When school programs or recitals are held during the school day, parents may be at work and unable to attend all events. If parents are needed to supervise fieldtrips, some workers may find that they lose money in tips or hourly wages that keep the family afloat. In addition, other issues may complicate the ability for parents to be involved. Lack of transportation or money for bus fare, arranging longer child care, knowledge of school rules or policies, and communication from the school about events or meetings that are taking place are just a few of the complicating issues according to Griffin and Galassi (2010). Parents may also feel that school staff does not trust them or that there is a judgmental attitude toward them by staff (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). If teachers think the parents don't care, but in reality, they can't take time offwork or may jeopardize the scheduling of others, parents may decline to get involved in order to keep their jobs and please the boss. Not Always a Welcome Environment Some cultures view education differently and parents may not know how to interact with the school or feel that the education of their children is for the school to deal with without their involvement. Some cultural and ethnic backgrounds have values that differ from what the perceived "American" values are, and therefore teachers may look upon parents with differing values differently and see them as uninterested or unconcerned, when in fact the parents may be interested, but just value education differently than is perceived by teachers (Amatea & WestOlatunji, 2007). Some cultures value education very much and believe minimal parental 18 influence will allow the educational experts to take over and make all decisions. While some parents may be unable to be involved, others may be unsure when to become involved, and are reluctant based on how the school has treated them in the past. They may also feel the school will treat them unfavorably if they become involved. When parents only receive negative feedback, a parent may feel intimidated to come to school in fear of being lectured on parenting. School staff may seem to have a common understanding of what they expect from parents, but this may not be understood by parents or communicated to them. Parents may be unsure about what their role is in their children's education, how they should help, or when they should step in and assist (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). As children approach middle and high school, parents often feel that some of the responsibility, such as homework, should shift from them to their child. Depending on the parents own level of education, some may find homework beyond their understanding and ability to assist. However, some parents do not know when they should step in to ensure everything is okay and homework is being completed, while also trying to promote responsibility and let their children do things on their own (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). While some parent involvement naturally decreases around the time children enter middle or high school, some parents are less involved because they feel like they know less about the curriculum and how to help their children (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). Parents may be unsure how to help with homework and may not engage in helping their children or become involved with the school because they feel they lack the communication, confidence, knowledge, and skills that are utilized by school staff (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). These types of parents may be seen by school staff as not caring about their children or hard to reach, when in reality the parents doubt their own abilities. 19 Other parents may avoid schools because of negative experiences they had in the past, as former students themselves or with their own children. Parents may feel when they are contacted by the school it is usually just to deal with some sort of problem or when something is wrong. When they are contacted, they are sometimes talked down to or blamed for incidences and spoken to by school staff in a business-like fashion (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). If parents avoid the school system because they feel they are not treated respectfully and only contacted when something is wrong, perhaps school staff should consider making regular phone calls to parents to let them know their children have done well, while also communicating in a tone of genuine care and respect. Griffin and Galassi (2010) reported that sometimes parents are not informed until two or three days have passed since an incident at school has taken place, which then makes it difficult for parents to discipline their children in a timely manner. Parents suggested that teachers be proactive about responding in a timely manner, especially in regard to misbehavior. Parents can't always "drop everything" and show up on the step of the school to deal with issues in a minutes' notice. In research by Griffin and Galassi (2010), one parent stated she would have been more involved in parent meetings and programs, but when she did attend, it felt like the only progress of the meeting was going through updates from the last meeting versus taking the time to talk about some of the issues the parent's child was experiencing. The parent also stated that having some sort of speaker on a relevant topic would have been beneficial as well. Various barriers seem to impede the involvement of parents in their children's education, which suggests there is a need to further engage and include the parents. 20 Strategies to Increase Parent Involvement School counselors have many responsibilities within the school, ranging from working with individual students, providing classroom lessons to participating on students' teams and collaborating with parents and others. The American School Counseling Association (2011) national model states, "National standards offer an opportunity for school counselors, school administrators, faculty, parents, businesses and the community to engage in conversations about expectations for students' academic success and the role of counseling program in enhancing student learning" (p. 4). Therefore, school counselors may be responsible for working with school staff, families, and the community to create the best possible learning environment for students. AJ:latea and West-Olatunji (2007) suggested that there are three primary roles that school counselors should have as leaders, which include: teaming with teachers to create welcoming and family-centered school environments, working with teachers to connect students' lives with the curriculum, and bridging together the gaps between teachers and students. Getting parents involved may seem like a huge task, but there are many small things that school counselors can do to ensure that every effort possible is made to get parents involved with the education of their children. Strategies for bridging together parental involvement and the school system are addressed in the literature regarding aspects of what school counselors can do. First of all, it is important to work with school staff, such as teachers, to get them on board. Some teachers may want parent involvement, but may subtly discourage it or hold negative views toward parent involvement (Lomb ana & Lombana, 1982) and teachers who see parents as uninvolved may actually come to expect less from those children in the classroom (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). 21 School staff may also view low-income parents and students as inferior or think that they are in their financial position due to poor attitudes, behaviors, lack of motivation and work values (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). School counselors can help teachers and school staff not only see the importance of parental involvement, but how it benefits children, by sharing the truths about those living in poverty, and also giving some suggestions to teachers and other school staff about reaching out in a welcoming manner to others. Teachers should understand that when parents are blamed for their children's downfalls, or when they feel that they are, that parents often become defensive and this often disrupts the ability for teachers to work with the parents (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Also, when parents feel there may be conflict between them and the school they, like most individuals, may automatically react by deflecting or avoiding the situation to avoid a sense of humiliation, guilt, shame, or embarrassment on their part (Clark, 1995). Knowing how to approach parents and communicate in a way to avoid conflict or any potential defensiveness that will only push parents further away from the school, is helpful not only for teachers, but also for increasing the likelihood for student success. Creating an atmosphere in which parents feel valued and respected is very important. School counselors can help staff see that it is important to communicate with and include parents through many forms of communication, and that parent involvement is important and more likely to happen when parents feel welcomed (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). There are many ways that parents can feel involved and since they know their children well, they can often be of assistance to teachers in learning more about his or her students. For example, a teacher could ask parents to share information about their children during the first week of school, which could in turn be helpful to teachers as they assist children with 22 learning opportunities in the classroom (Griffin & Galassi, 2010; Walker, Shenker, & HooverOempsey,201O). School counselors can also encourage teachers to have some sort of homework or family centered projects to work on together at home (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). Homework that requires students and their families to work together, not only creates an opportunity for positive interactions at home, but is also a small way for parents to feel involved if they are unable to come to the school. Amatea and West-Olatunji (2007) suggested that parents can also help their children reach goals. For example, if a parent has a goal for their child to increase literacy, instead of working on the goal only in the classroom, a teacher could invite the parent to the school one night a week to make story books that assist with reading or have them work on a family-related project to help the child with reading. This way the parents are involved, able to celebrate their family culture with their child, and can be present to help the child succeed in school with established goals. It was also suggested that families could be interviewed, preferably in the beginning of the school year, about their "funds of knowledge" so teachers could learn more about the families and build this information into the classroom and curriculum. Funds of knowledge are basically the values, skills, and knowledge that families have acquired or built, and the focal point from which the family may perceive things and learn. The funds of knowledge will not only vary from family to family, but also by economic status and cultural backgrounds (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Therefore, just one way oflearning or one singular curriculum in the classroom may not universally fit each and every student. However, knowing more about each family and student could help teachers adjust curriculum to students, which may greatly help children succeed in the classroom. 23 School counselors can also collaborate with school staff to discuss the benefits of parent involvement, any potential barriers, and how teachers may hold misperceptions about why parents sometimes are not involved and inform them about differences in values and culture that may exist between families and the school (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). If necessary, a survey could be given to school staff to identify if staff needs to learn more about this topic and if there is a need, school counselors could talk with staff further about parental inclusion with training to review the barriers and importance of parental involvement (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). The downfall of implementing interventions, such as those previously described, with teachers are the perceptions teachers sometimes hold against school counselors. Some teachers may feel that the role of a school counselor is solely to work with students and not with staff (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). If teachers are willing to work with school counselors, and it may only be with those who are interested, teachers and school counselors could learn more about students, families, and how children learn in the home by visiting some families and conducting surveys (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Information about how parents interact with their children and how children learn at home could then be useful in incorporating some of it into the classroom. It may be timeconsuming, may not be seen as beneficial to some, and there may be some school districts that do not feel comfortable with school staff reaching into the homes of families out of respect of privacy. School staff could also collaborate to put together workshops or professional development events that were focused on working with culturally 24 diverse families, redesigning curriculum, and using effective classroom management with all students, with the goal of helping teachers identify student and family interests and strengths (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). School counselors can also give advice to school staff about how to appropriately communicate with parents. Walker, Shenker, and Hoover-Oempsey (2010) suggested that staff could learn more about how to use interpersonal communication, such as using open-ended questions, building rapport, and using appropriate eye contact or word encouragers; all reinforce the importance of becoming effective active listeners. By using open-ended questions, parents are encouraged to share more than just a yes or no response. When listening to parents, reflecting and paraphrasing what the parent has said is also helpful. For example, a teacher could say "I hear you saying ... " so that the parent feels heard, understood, and trusted. If the parent does not feel understood by the teacher, the way in which this question was originally phrased gives parents the opportunity to clarify and explain further. Walker, et al. (2010) also suggested using non-threatening questions so parents do not become defensive. If a teacher would like more information about a student, a way to ask this is, "To help me get a better understanding of your son, tell me more about him." It is also important for teachers to understand that when parents do not feel involved and communicated with, that their involvement with the school is likely to decrease (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). School counselors are often a central point of communication for families and school staff; therefore, they should be approachable, friendly, and helpful. Some of the first communications families have with schools could very well be with the school counselors. It is important that they set a good first impression with families, as school counselors are professionally trained and an important asset for bridging school, community and families 25 (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). Walker, et al. (2010) indicated that school counselors should treat all in an honest, trustworthy, open, caring, and positive manner. School counselors can also create awareness and advocate for school staff to treat minority and immigrant families, as well as those who have varying family compositions, such as children living with extended family, same-sex parents or in foster homes, in a consistent, fair, open, and sincere way and by doing so is just one of the ways to overcome the feelings of mistrust and powerlessness that parents may feel toward the school (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). School counselors can help students by working to increase parent involvement by not only working with all staff, but by looking at processes within the schools that deal with parent involvement. Since 2001, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) has been a focal point in the schools. One premise ofNCLB is the importance of parental involvement as an important way to help children succeed academically (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). A reoccurring theme found in literature is the need for schools to have two-way communication that sends the message that everyone is working together, versus information that comes to the family one way via a hierarchy within the school (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Creating an open, warm and inviting environment with two-way communication for parents can be accomplished by school staff contacting parents for both positive and negative situations, asking for parents' input, finding opportunities to get parents involved in the school, and teachers sending welcome letters or messages that require parents to reply (Amatea & WestOlatunji, 2007). School counselors hold an important role in helping teachers and other staff members see the importance in working together to get families involved and also being the connecting piece between not only the school and families, but also the community to encourage 26 families involvement (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007; Van Velsor & Orozco, 2007; Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). Team meetings for students are often held at school and present another opportunity for school counselors to promote parent involvement. School counselors can ultimately model how to involve parents, set the tone for cooperation from all, as well as the importance of not blaming parents, for their children's performance in school (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). It is also important to help the team brainstorm how to get low-income parents involved with their children's education, whether they are physically able to come to the school or not (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). During meetings, parents and students should be invited to participate and encouraged to share their viewpoints. If the meeting is all negative, the likelihood that parents will want to attend on a regular basis will be lower than if strengths, as well as areas for improvement, are discussed. Staff can be encouraged to pull all this information together in the meeting to provide an action plan to move forward in a way that expresses everyone is working together as a team (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007). Working with parents to engage in school activities is probably one of the most crucial aspects of ensuring student success. School counselors can help staff see the importance of helping parents to become more involved, but also playa pivotal role in working to get parents involved. How parents perceive their involvement is important to understand as those who feel they are needed, effective and have skills to put forward are more likely to be involved than those who feel it is just another demand that takes away from their time and energy (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). 27 One of the first things that can be done is to get parents in contact with other parents, especially those who may be in similar situations as them. School counselors could organize parent networks that connect them with one another, the school, events, and resources, while also modeling how to work with the school. Ideally, it is thought that families who reach out to one another could possibly go on to support each other, not only with their children's education, but also outside of school (Amatea & West-Olatunji, 2007; Griffin & Galassi, 2010). This could be especially helpful for families living in poverty as they may be able to help each other with transportation, child care or in other ways. Research by Lombana and Lombana (1982) suggested that there are numerous ways school counselors can work directly with parents. School counselors are usually knowledgeable about agencies or resources in the community and can refer families to them for assistance and support. Parents may seek family counseling from a school counselor, but this is seldom a duty that falls within the role of a school counselor, and would be an example of a situation in which parents could be referred to an outside agency. It may be appropriate for school counselors to collaborate with other staff, such as social workers, to identify families who seek extra resources or services to help them succeed (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). In regard to volunteering in the school, some parents may feel comfortable jumping into activities and events, while others may prefer more behind-the-scenes level of involvement. Lombana and Lombana (1982) stated that school counselors could work to get parents connected with volunteer opportunities in the school, whether it is directly helping children in the classroom, on a field trip or non-directly by working on a newsletter, helping with a fundraiser, or putting together student handbooks. It is imperative that parents feel comfortable with the 28 task they are doing, so it is important to take this into consideration when matching them to an activity. The Lombanas (1982) highlighted one school that went as far as creating a parent room in the school so that parents felt valued and welcomed, as they had a place of their own to collaborate and work on projects. Overall, parents need to be encouraged. Parents may feel that no one cares about them or their family's needs, so school counselors can empathize with what they may be going through, but also help parents see how to properly communicate, motivate, and discipline their children so the parents feel they are capable and have control (Clark, 1995). In addition to having parents volunteer in the school, there are also other ways to help parents become involved and guidelines that school counselors can utilize to build rapport with parents. The following ideas to increase parent involvement were suggested by Walker, Shenker, and Hoover-Oempsey (2010). For those families that are able to come to the school, family events or nights can be organized to allow families the opportunity to be involved with activities they may otherwise not have access to or know how to do. For example, the school could host chess lessons, and math or science nights. Community organizations could be invited into the school to teach families new skills or to help children involved with activities such as youth scouting programs. If parents are unable to attend these events or other school functions due to their schedules, this should be addressed and school counselors can make every effort possible to eliminate barriers such as transportation or child care. Counselors could even consider home visits hosting events at various community centers or buildings throughout the area that could make involvement easier for some families. Parents, even if they are not involved, often have skills they can share. Parents can be recruited and utilized as leaders to share their knowledge at school fairs or assemblies, which would most 29 likely in turn, empower them to see they are a valuable asset to the school and do have skills they can contribute. When parents lack skills or don't feel confident, they can be offered ideas to enhance their parenting skills or resources that could assist them. New parents should always be invited into the school so they feel involved and welcomed from the first possible opportunity. Finally, Lombana and Lombana (1982) stated that meetings with parents should be scheduled at a convenient time, and parents should be treated respectfully, listened to empathetically, offered suggestions when asked, be provided with all necessary information, involved in activities that make sense to them, and given feedback on their contributions and progress. Making Time in a Busy Schedule School counselors are tasked with working with students to promote their academic, social, and personal success, so it is easy to see that on top of these requirements, finding the time to collaborate with school staff and parents to increase parent involvement and student success of students living in poverty, may be a strain. With their already overloaded responsibilities, school counselors may feel they have limited time and energy to tackle another task. However, as discussed earlier, children living in poverty may have parents who are rarely involved, and may be at a higher risk for academic struggles if there is no attempt at any sort of intervention. Amatea and West-Olatunji (2007) suggested that school counselors who feel stretched too thin should speak with their principals about the importance of helping low-income students succeed, especially by getting their parents involved. Perhaps they could then work together so the school counselor's role could be renegotiated a bit, allowing for more time to work on making improvements. In addition, they stated that school counselors can expand their 30 leadership abilities when working in high poverty schools by creating a more family-centered school environment, partnering with staff to design culturally relevant curriculum, and working as a negotiator between the staff, families, students, and the community. Finally, when students are assigned to school counselors by the alphabet, it is helpful so that families with many children are familiar with one school counselor as a reference point versus many if it is a large school (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). In the event that parents have children with different last names, it would most likely be in the best interest of the children and the parents to have one counselor assigned to the whole family if possible. This would also make it easier for parents so they could work with one counselor and not have to meet with and/or contact separate counselors for each child. Research Models that Support Parent Involvement All parents have different needs of a school counselor, so it is important when meeting with parents or communicating with them; to distinguish what types of support they are seeking (Lombana & Lombana, 1982). Lombana and Lombana (1982) discussed the home-school partnership model that explains four different areas of support that parents may need from school counselors. The model is explained as a triangle with four levels stacked on top of each other. At the bottom level is parent involvement, then parent conferences, parent education, and parent counseling at the top. The base of the triangle is bigger and therefore represents that more parents are in need of parent involvement support. The top section of the pyramid, parent counseling, represents the section where parents need the least support. The bottom level, parent involvement, indicates the need for parents to feel attachment to the school. They also need to have necessary information, the ability to communicate with staff, and to feel connected with the school. Within the next section of the model, some parents are required to attend or feel a need 31 to have conferences with counselors, teachers, or other staff. The third level, parent education programs, affects about one out of every five parents and includes those parents who need to be taught effective ways to discipline and communicate with their children. The top section of the pyramid, which affects about one in twenty parents, represents parents who need parent counseling. As stated earlier, this is rarely an appropriate task for school counselors and most of the time these parents should be referred to outside agencies. When working with parents, it is important to understand the various needs of parents, what they may need from the school counselor, and how the school counselor can reach out to them. This model helps school counselors to see that the majority of parents on the lowest level of the model just need to be involved in the school and feel a sense of connection with the school. A second model that can be used to examine parent involvement and how to increase it in schools is the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler's model of parental involvement (Griffin & Galassi, 2010; Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). This model discusses why parents become involved, what involvement looks like, and how involvement influences student achievement by looking at how school counselors can be the connection between home and school (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). The following are the five levels of the model in order starting with level one: parent perceptions of involvement, types of parental involvement, student perception of the learning methods utilized by parents during involvement, and the fourth and fifth have to do with outcome measures surrounding student achievement (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). The model is complex, so for the purposes of this review, only level one and two will be discussed as the remainder deal with what happens after parents are involved. Level one of the Hoover-Dempsey and Sandlers parent involvement model discussions why parents become involved and what motivates them to do so. Walker, Shenker, and Hoover- 32 Oempsey (2010) explained that there are a variety of reasons why parents may become involved with their children's education, such as invitations sent to parents from the school. This is why it is important for school counselors to help school staff see the importance of making connections with parents so they feel welcome. Parents may also be influenced by what they feel their role is in helping, how much they feel they can help their children, their time, energy, knowledge, skills, and family culture regarding involvement in the schools. Other factors that may shape parent involvement include socioeconomic status, resources, and parent level of education. Overall, Walker, Shenker, and Hoover-Oempsey (2010) stressed that the relationships between schools, parents, and students are imperative if parents are to become more involved in the school setting. It is also important that parents feel welcome and that they feel they are needed and helpful when they do become involved (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). Level two of the model discusses the various types of parental involvement and skills utilized by parents during involvement. For example, the degree to which parents offer encouragement, reinforcement, instruction, or modeling while they are involved would be explored (Griffin & Galassi, 2010). The different ways in which parents can be involved are at school, by parent communication with the school, and helping children with homework at home (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). Also intertwined into the various ways parents can be involved are the parents' expectation of student achievement and the goals parents have set for their children. These expectations for their children are often predictors of the student outcomes in the higher four and five levels of the model, and therefore parent expectations for their children are important (Walker, Shenker, & Hoover-Oempsey, 2010). 33 Levels one and two of this model can be beneficial for school counselors as it helps them understand why parents get involved and how they do so. While it may not be possible for school counselors to change parental expectations for their children, school counselors can use this information to intervene and help parents become more involved. A parent who is involved at home may lack the confidence to become involved with activities at the school until they are encouraged, invited, and made to feel welcomed. School counselors could help the parent in this example to get involved not only at home, but also in school, to help the student have better educational outcomes. In another example, a parent may feel he or she does not need to help their child at home and therefore the student may be struggling. If the school counselor could help the parent see the benefit of becoming more involved at home, perhaps the student would do better academically. In addition, if the parent is more involved at home, the child may have a different sense of what is expected by his or her parent, and may do much better because the child feels more is expected. Overall, this model helps school counselors get a picture of why certain parents may not be involved and help them brainstorm how to get parents, especially low-income parents, more involved to help children succeed and achieve in school. In summary, parents generally want to attend school events. Perceive barriers to making it a priority include work situations, money for gas or public transportation, missed time at work may indicate missed income, cultural misunderstandings, language barriers to understanding responsibilities and a feeling of being judged by educators. Previous experience with their own school settings when they were younger may also cast a shadow of doubt on their ability to handle school situations as parents. When educators and administrators talk down or blame 34 parents, it can make a return visit a challenge for the belittled parent. School counselors can work with other school administrators and leaders to help remove barriers by informing staff about ways to reach out to parents and help them realize everyone wants the best for the children. When all parties work together, children may feel supported at home and at school by the partners in education who can help them find success in school and in the community. 35 Chapter ill: Summary, Discussion and Recommendations Summary Children seem to benefit from parental involvement in the school and family dysfunction, along with the disadvantages of living in poverty may present negative outcomes in academic achievement in school. There are perceived barriers to getting parents more involved, yet parent involvement may be the very factor that could boast academic achievement. Parents may willingly choose not to participate with the school or may be unable to become more involved for several valid reasons. For some parents living in poverty, daily life is hectic and one or both parents may work several jobs, long hours, have other obligations at home, or simply just have no additional time or resources to become involved even if they wanted. Other parents may not become involved because of the language barrier, cultural beliefs about education, negative perceptions of school, their lack of confidence about their own skills, or feeling they are mainly only contacted by the school for negative incidences. Other parents may have experienced negative experiences in school personally and still remain unsure about the outreach services provided by schools. Therefore, school counselors can be utilized as a connection between the school, students, parents, and community to support parent involvement and potential increased student academic achievement, especially for those living in poverty. Living with poverty not only creates hardships for many parents, but is also detrimental for some children. Children living in poverty may be at an increased risk for mental health issues, as are their parents, but also for academic struggles, school failure, crime, abuse, neglect, and some may live with parents who are abusing drugs or alcohol. This chaotic and unsupportive environment may influence the level of success students experience in school. Parents may have low expectations for their children's education, may not create a conductive 36 environment for learning at home, nor assist their children with tasks such homework. Helping parents become more involved in school, even on an entry level, could greatly increase the changes of children succeeding in school. Van Velsor and Orozco (2007) found that there was a positive relationship between parental involvement and children's academic success. It still appears that parents living in poverty or family dysfunction are less likely to become involved with their children's education, resulting in additional factors contributing to a child's struggle both academically and socially at school. Research in the literature focused on getting parents involved and some may perceive this as a potential if the approaches and models discussed are used. However, it may be the case that some parents are going to be resistant and defiant no matter what approaches are utilized. There appears to be limited research on the topics that address parental involvement if they are unwilling. Even after removing perceived barriers, parents may still decline the outstretched hand of assistance as they prefer to remain aloof and distant in the educational process. School leaders can only do so much and cannot change parents' thoughts, beliefs, or perceptions about involvement ifparents aren't willing to at least meet them halfway. The literature review suggested ideas for school counselors and even went another step further to identify two models that could be used to increase parental involvement. The homeschool partnership model explained that parents may seek school counselors for one of four reasons including: parent involvement, parent conferences, parent education, and parent counseling. However, the majority of parents just need to feel involved with the school, invited and informed. The Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler's model of parental involvement presented five levels to develop relationships with parents, however, level one and two were the most relevant as they 37 discussed why parents get involved and how they do so. This model identifies why some parents become involved and also why others may not and also explored the various methods in which parents can be involved, such as by helping with homework, participating in school activities, or communicating with school staff. This model is deemed helpful as it can be used to determine how to get some parents involved if they are not. While school counselors may not be able to change parents' perceptions about their involvement, they can present ways parents can become involved, which may influence parent perception about involvement and the benefits for their children. Discussion The ASCA National Model (2011) for school counselors, suggests that one role of a school counselor is to bring together the school, family, and community. Research indicated this could be done in several ways, such as working with teachers, school staff, developing school policies and procedures and practices of the school counselor, and overall being an advocate for change by informing others and ultimately modeling how to make it happen. Teachers mayor may not understand to what extent they can influence how parents become involved. They, along with other school staff including custodians, secretaries, bus drivers and food servers, are encouraged to create a warm and welcoming environment for all that includes two-way communication, open-ended questions, and opportunities for the parents to become involved whether in the classroom, or at home with a family homework activity. Teachers can also collaborate with school counselors to gather information regarding the children's home life, parental needs and expectations in order to better serve them while bringing learning from the classroom into the homes. As teachers develop more appropriate curriculum so children can be successful, parents should be contacted for both positive and negative feedback 38 and communicated with in a way that is respectful and conveys the message that everyone is working together in the best interest of the children. School counselors can use all of these strategies when working with parents and children, but can also take it a step further to pull everything together. As school counselors are often the central source of communication for parents, counselors should make every effort to communicate trust, openness, respect, and empathy. In addition, meetings should be scheduled at a time when parents can be involved. The school counselor can try to reduce any perceived barriers, such as childcare or transportation and can connect families to community resources, outside agencies or other families that may be able to support one another. School counselors can also find opportunities to get parents involved in the school whether contributing to a project or helping out in a classroom. Overall, school counselors are instrumental as they try to brainstorm solutions to problems and create a welcoming environment for parents where everyone works together to help all children succeed. Recommendations for Further Research More research needs is needed to study optimal parental involvement in schools. While it is recognize there are overly engaged parents and much research on that topic, for the under involved parents, more research is needed. As the population changes and immigrants enter the country, some wish to remain hidden and unnoticed to avoid being sent back to the home country. By remaining in the background, they raise their families with minimum contact with community agencies including schools. Perhaps further research would yield other suggestions of how to get parents involved with the goal of increasing student academic success. Also, little research was found on work with the difficult parents who see no value in becoming involved. It is recommended that more research be conducted on these topics in the 39 future to give a more rounded approach to this topic. Maybe research assessments need to be provided in the native languages of populations who are absent in being engaged with schools. In summary, school counselors seem to hold a very important role in helping families by getting parents more involved so that children succeed academically. It is recommended that school counselors take an active role in doing what they can to get parents more involved. School counselors may already feel overwhelmed with multiple tasks and roles, leaving them feeling as though they are unable to take on another. However, research shows the parental involvement is important, not only to children living in dysfunction or the disadvantages of poverty, but to all children. To work toward improvements, school counselors can use the models addressed in this review to look at what assistance parents need and also why they become involved and how. From there, this information can be used, in conjunction with the suggestions in the literature, to get parents more involved in the best interest of the children. 40 References Amatea, E., & West-Olatunji, C. (2007). Joining the conversation about educating our poorest children: Emerging leadership roles for school counselors in high-poverty schools. Professional School Counseling, 11(2), 81-89. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.1ib.uwstou t.edu: 2699/ehost/detail?vid=23&hid=3&sid=9bdb52d7 -6917 -43a8-b3d 1-be06936b87 01 %40s essionmgr 13&bdata=J nNpdGU9ZWhvc3 QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&AN= 28027600 American School Counselor Association. (2011). School counselor competences. Retrieved from: www.schoolcounselor.org/files/SCCompetencies.pdf Benner, A, & Mistry, R. (2007). Congruence of mother and teacher educational expectations and low-income youth's academic competence. Journal ofEducational Psychology, 99(1), 140-153. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.140 Bennett-Johnson, E. (2004). The root of school violence: Causes and recommendations for a plan of action. College Student Journal, 38(2), 199. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.1ib.uw stout.edu :2699/ehost/detail?vid=25&hid=3&sid=9bdb52d7-6917 -43a8-b3d 1-be0693 6b870 1%40sessionmgr 13&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h& AN=14098754 Clark, A (1995). Rationalization and the role of the school counselor. School Counselor, 42(4), 283. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.1ib.uwstout.edu:2699/ehost/detail?vid=27&hid=3& sid=9bdb52d7-6917-43a8-b3d1-be06936b8701%40sessionmgr13&bdata=JnNpd GU9ZWhvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&AN=9506020046 41 Griffin, D., & Galassi, 1. (2010). Parent perceptions of barriers to academic success in a rural middle school. Professional School Counseling, 14(1),87-100. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.uwstout.edu:2699/ehostldetail?vid=29&hid=3&sid=9bdbS2d7-69l'743a8-b3dl-be06936b8701%40sessionmgrI3&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2Z Q%3d%3d#db=a9h&~=S4626961 Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2010). Involving low-income parents and parents of color in college readiness activities: An exploratory study. Professional School Counseling, 14(1), l1S124. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.uwstout.edu:2699/ehost/detail? vid=12&hid=3&sid=9bdbS2d7-6917-43a8-b3dl-be06936b8701%40 sessionmgrI3&bdata=JnNpdGU9Z Whvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&~=178661S Lambie, G., & Sias, S. (200S). Children of alcoholics: Implications for professional school counseling. Professional School Counseling, 8(3),266-273. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.uwstout.edu:2699/ehost/detail?vid=ll&hid=3&sid=9bdbS2d7-691743a8-b3d I-be06936b870 1%40sessionmgrI3&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGI2ZQ% 3 d%3d#db=a9h&~=16182121 Lombana, 1., & Lombana, A. (1982). The home-school partnerships: A model for counselors. The Personnel and Guidance Journal. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.uwstout.edu:26 99 lehost/detail?vid=31&hid=3&sid=9bdbS2d7-6917-43a8-b3dl-be06936b8701 %40 sessionmgr 13&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&~=64624 76 Poverty in the United States. (2010). Congressional Digest, 89(10),298-300. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.uwstout.edu:2170/ehostlpdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=427aa4aa-e2eS4b41-9877-924eb4468b43%40sessionmgrI2&vid=24&hid= 17 42 Russel, M., Harris, B., & Gockel, A. (2008). Parenting in poverty: Perspectives of high-risk parents. Journal of Children and Poverty, 14(1),83-98. doi: 10.1080/1079612070 1871322 Van Velsor, P., & Orozco, G. (2007). Involving low-income parents in the schools: Community centric strategies for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, Jl(1), 17-24. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib .uwstout. edu :2699/ehostldetail ?vid=3 5&hid=3& sid=9bdb52d7-6917-43a8-b3dl-be06936b8701%40sessionmgrl3&bdata=JnNpdGU9Z Whvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&AN=272643 3 9 Walker, 1., Shenker, S., & Hoover-Oempsey, K. (2010). Why do parents become involved in their children's education? Implications for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 14(1),27-41. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.1ib.uwstout.edu:2699/ehost/ detail ?vid= 3 6&hid=3 &sid= 9bdb52d7 -6917 -4 3 a8-b3 d I-be0693 6b8 701 %40session mgr 13&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGI2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ehh&AN=54626956 Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. (2011). "What is the NCLB?" and ten other things parents should know about the No Child Left Behind Act. Retrieved from: http://dpi.wi.gov/esea/pdf/parents.pdf