Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto

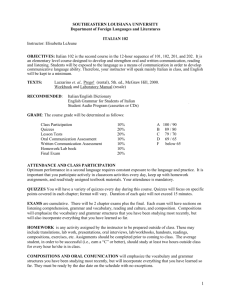

advertisement

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto:

A Distributed Morphology Analysis

Andrea Calabrese

Calabrese, Andrea(2012), “Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed

Morphology Analysis,” Language & Information Society 18. Many Italian verbs display stem

alternations with highly idiosyncratic vocalic and consonantal allomorphy in the paradigm

of the simple past. Due to their complexity, these alternations are often used by linguists as

evidence for models assuming rote memorization of stem alternants and endings (see the

recent work by Maiden 2005, 2010 for example). In this paper, I will show that these alternations are characterized by basic regularities and that a rather simple analysis of them can be

formulated in the framework of Distributed Morphology (DM) (Halle and Marantz 1993;

Embick 2010; Embick and Marantz 2008). In particular, this analysis involves notions such

as roots, Vocabulary Items and Readjustment Rules as predicted by DM. There is no evidence

for memorized stem alternants. Instead, the allomorphy we see in the Italian Passato Remoto

is readily accounted for by providing an appropriate morphosyntactic analysis of the forms and

by deriving the irregular alternants from single underlying roots by means of Readjustment

Rules. This paper also shows that it is crucial that the rules accounting for this allomorphy

obey a strict definition of locality requiring linear adjacency. This explains why the presence of

I would like to thank Morris Halle, David Embick, Diego Pescarini, three anonymous reviewers

and especially Jonathan Bobaljik for their comments and helpful suggestions on a previous draft of

this paper.

University of Connecticut

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 1

the Thematic Vowel prevents their application. In the irregular forms where these rules apply,

the Thematic Vowel is removed by a special pruning rule. Crucially, Impoverishment removes

a diacritic index associated with the application of this pruning rule in certain morphosyntactic contexts (in the 1st and 2nd pl., and 2nd sg.), thus the regular basic form of the root will

appear in these contexts. Impoverishment in this case is motivated by a general Markedness

principle that disfavors complex exponence in morphologically marked environments.

keywords: allomorphy, stem alternations, Distributed Morphology, roots, vocabulary items,

readjustment rules, locality, impoverishment, morphological markedness, Italian

verbal morphology, Italian stress system

0. Introduction

Many Italian verbs display stem alternations with highly idiosyncratic vocalic and

consonantal allomorphy in the paradigm of the simple past, what is traditionally

called Passato Remoto in Italian grammars—in this paper I will use this term to refer

to this tense. Due to their complexity, these alternations are often used by linguists

as evidence for models assuming rote memorization of stem alternants and endings

(see the recent work by Maiden 2005, 2010 for example). In this paper I will show

that these alternations are characterized by basic regularities and that a rather simple

analysis of them can be formulated in the framework of Distributed Morphology

(Halle and Marantz 1993; Embick 2010; Embick and Marantz 2008). I will show

that the best synchronic analysis of the Italian Passato Remoto morphology involves

notions such as roots, vocabulary items and readjustment rules as predicted by DM.

In particular, I will propose that the irregular allomorphy we see in the Italian Passato

Remoto is readily accounted for by providing an appropriate morphosyntactic analysis of the forms and by deriving the alternants from single underlying roots by means

2 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

of Readjustment Rules, phonological operations operating under morphological conditions. No memorization of stem alternants and endings is needed.

A sample case of the allomorphy found in the irregular forms of the Passato

Remoto is given in (1) where we see alternations between 2nd and 3rd person plural

forms.

(1) perdeste

persero

‘lose-Past-2nd pl./3rd sg.’

In the 2nd pl., there is a thematic form of the verb—i.e., a thematic vowel (TV) follows the root1)—and the form of the root regularly appearing with other tenses is

found (cf. perd-e-t-e ‘pr.Ind -2nd pl.’, perd-e-v-a-te ‘Imp.Ind-2nd pl.’, perd-e-re ‘inf’).

In contrast, in 3rdpl., we have an athematic form of the verb—no thematic vowel is

present after the root and the stem undergoes changes in phonological shape, specifically addition of the consonant /s/ (cf. spensero, vissero)—actually an exponent of the

past Tense, as argued later—with subsequent deletion of the final root consonant /d/

(i.e., perd-s-e… → per-s-e-…). The 1st pl. and 2nd sg. behave like the 2nd pl.; in contrast, the 1st and the 3rdsg. behave like the 3rd pl. Therefore, we have the paradigmatic

alternations in (2):

(2) Singular

1

2

persi

perdesti

3

perse

Plural

1

perdemmo

2

perdeste

3

persero

‘lose’

There are 200 verbs in Italian that share this basic pattern, let’s call it a regularity

1) To understand alternations such as that in (1) an important feature of Italian verbal (and also nominal) morphology must be considered: the presence of a vowel, the so-called Thematic Vowel, after

the verbal root and other functional projections. This important aspect of Italian (and of Latin and

other Romance languages) will be discussed in detail below.

(i) perd-e-v-a-no/perd-e-ss-i-mo ‘lose-imperf3pl./ imperfSubj1pl.’

(schematically: [[[[perd]root -eTV-]V -v-T-aTV-T]- no]AGR/ [[[[perd]root -eTV-]V -ss-T-iTV-]T -mo]AGR)

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 3

in the irregularity: in the 1st and 3rdsg. and 3rdpl., they have an athematic form of

the verb and the root undergoes the idiosyncratic phonological changes characteristic of this tense. In the 1st and 2nd pl. and 2nd sg., there is a thematic form of the

verb and the form of the root regularly appearing with other tenses is found. Stress

shifts are also associated with these alternations. The irregular forms receive stress

on the root—the traditional literature calls them rhizotonic. The thematic forms

instead receive stress on the thematic vowel—these forms are traditionally called

arhizotonic.2)

(3) Irregular: [[[[pérd]root ___]V -s-]T i]AGR

pérsi

Athematic

vs.

Regular: [[[perd]root-éTV-]V -sti]T+AGR3)

perdésti

Thematic

Notice that despite this unifying regularity, the surface shape of irregular forms may

be quite different: specifically, the exponents of the past tense in the irregular forms

may be different, and different morphophonological operations may also apply in

their context. I provide a sample of the alternations found in the irregular forms of

the Passato Remoto in (4).

(4) i. Exponent /s/:

No change:

valeste/valsero ‘be worth’ (Root: val)

Deletion of final coronal stop:

perdeste/persero ‘lose’ (Root: perd)

Assimilation of final consonant: viveste/vissero ‘live’ (Root: viv)

Assimilation of final consonant + degemination:

speɲɲeste/spensero ‘turn off’ (Root: speɲɲ)

Changes in vowel quality:

espelleste/espulro ‘expell’ (Root: espell )

2) Traditional accounts assume that stress position is fundamental to accounting for the distribution

of regular/irregular stem forms. In section 5, I demonstrate that stress in verbal forms is predictable

and that its distribution is in part related to the presence /absence of Thematic Vowels. I defer discussion of stress to that section. I will not mark stress in the examples unless an accent is required

by the Italian orthography.

3) I assume that there is fusion between Tense and AGR in the regular form of the verb. See section 3

below for discussion.

4 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

ii. Exponent /Ø/:

a. With gemination of the final

root consonant (the consonant

is also rounded if dorsal):4)

b. With changes in vowel quality:

veniste/vɛnnero ‘come’ (Root: ven)

tat∫este/takkwero ‘be silent’ (Root: tak)

faceste/fet∫ero ‘make, do’ (Root: fak)

videro/vedeste ‘see’ (Root: ved)

The paper provides an account for how the special allomorphs characterizing the

irregular forms are derived. Here is a brief sketch of how the allomorphs are derived

(see section 3 for more details). As mentioned above, the irregular stem allomorphs

are athematic as in (5). The thematic vowel that is always present in regular morphology is removed by a pruning rule—which I assume to be a Readjustment Rule—as

in Embick and Halle’s (2005) analysis of irregular forms in the Latin Perfect, the

ancestor forms of the athematic forms in (5). The exponents for the past morpheme

are given in (6). As will be shown in section 3, (6a) causes gemination and secondary rounding of the preceding consonant, where rounding is preserved only in

dorsal stops (see (4iia)). The surface phonological shape of the roots is accounted for

through the application of Readjustment Rules. If one disregards vowel changes5)

and some other minor phonotactic adjustments, two simple phonological operations

account for the surface forms of the roots: one is coronal stop deletion and the other

one is consonantal assimilation, where coronal stop deletion applies before the other

rule. Simplified derivations involving these rules are given in (7). (The symbol ^ indicates that the two elements must be linearly adjacent for the rule to apply (see section

1)). The reasons for having a diacritic index on the root will be discussed in section 6.

4) In the analysis developed below, this exponent is not null but actually involves a skeletal position

associated with [+round] secondary articulation.

5) Vowel changes in the root require special rules of ablaut. For example, one implements vowel

fronting in /fat∫/:

(i) /fat∫/-/Ø/-/e/ ↑ vowel fronting ↑ [fet∫e]

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 5

(5) [[[[perd]root ]V -s-]T -e ]AGR

+pst 3sg.

X

↔ [+past]T / RootL ^__ , when RootL = ven, tak, dʒak, etc.

|

Labial

|

[+round]

b. s ↔ [+past]T / RootS ^__ , when RootS = mett, viv, muov, perd, etc.

c. Ø ↔ [+past]T / RootA ^__ , when RootA = fat∫, ved, etc.

(6) a.

(7) a. /ven/-/Xw/-/e/ → gemination ↑ vennwe → removal-rounding → [venne]

b. /tak/-/Xw/-/e/ → consonant gemination → [takkwe]

c. /perd/-/s/-/e/ → coronal stop deletion → [perse]

d. /prend/-/s/-/e/ → coronal deletion → [prense] → coronal deletion → [prese]

e. /viv/-/s/-/e/ → consonant assimilation → [visse]

The phonological shape of the large majority of the irregular forms of the Italian

Passato Remoto can be readily derived by means of theoretical primitives and rules

like those mentioned above.

In addition to showing how the allomorphs of the irregular forms are derived,

another important goal of this paper is accounting for why there are the alternations

according to person-number in (1)-(2). Following Embick (2003, 2010, 2011), I

assume that rules dealing with contextual allomorphy (both Vocabulary Item Rules

and Readjustment Rules) apply under strict locality conditions. In fact, the rules

needed to account for the allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto require linear adjacency between the root and past tense. This readily explains why no special

allomorphy occurs in the forms in which there is a thematic vowel. The intervening

thematic vowel disrupts the adjacency that is required for the application of these

rules. The unmodified form of the root therefore appears since only regular morphology vocabulary items can be inserted in this case and, in addition, no Readjustment

6 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

Rule can apply. One of the contributions of this paper is then to provide evidence for

morphological rules that require linear adjacency to apply. In section 1, I address the

question why not all morphological rules appear to undergo this requirement.

Another contribution made by this paper regards a novel use of the operation

of Impoverishment (Bobaljik 2003; Bonet 1991; Halle 1997; Halle and Marantz

1993; Harley 2008; Nevins 2011; Noyer 1992, 1998). The issue is to explain why

the 1st and 2nd pl. and 2nd sg. Passato Remoto forms are thematic, or more precisely,

to explain why the rule that prunes away the Thematic Vowel does not apply in

their case. I will account for this fact by proposing the following: 1) the application

of Readjustment Rules requires the presence of special diacritic indices. In particular,

a root diacritic index is necessary for the application of the Thematic Vowel Pruning

Rule. 2) Impoverishment deletes this diacritic index in 1st and 2nd pl. and 2nd sg.

forms. The Pruning Rule therefore does not apply. The Thematic Vowel stays and

regular morphology will be inserted as discussed above.

The operation impoverishing the diacritic, however, is not arbitrary. In fact, I

will hypothesize that the ultimate (diachronic) cause of this operation is a markedness principle: Brøndal’s (1940, 1943) “Principle of Compensation”. This principle

states that marked categories tend not to combine. In Calabrese (2011) I interpret

this principle as stating that marked categories cannot have idiosyncratic exponence

when in combination with other marked categories. Special Vocabulary Items

and Readjustment Rules indeed create idiosyncratic exponence. Now the Passato

Remoto, and persons such as the 1st and 2nd plural are marked morphological categories. Therefore, according to the Principle of Compensation, idiosyncratic exponence

in the 1st and 2nd plural of the Passato Remoto should be avoided (see section 8 for

a proposal regarding the 2nd sg.) I propose that this is obtained by impoverishing the

diacritic index required for the application of the Thematic Vowel Pruning Rule; the

Thematic Vowel therefore remains with the consequences discussed above. In secAllomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 7

tion 5, I will discuss other cases from the Present and other tenses that show the same

markedness effect in the 1st and 2nd pl. As discussed in this section, the emergence of

regular morphology in the 1st and 2nd pl. in the Passato Remoto and these other

cases appears to be part of a general pattern characterizing Italian and Italian dialects. In fact, in many of these varieties, idiosyncratic exponence is avoided in the 1st

and 2nd plural by means of replacement of exponents (syncretism) or even removal/

omission of exponence (cf. in subject clitic systems (Calabrese 2011), in object clitics

(Calabrese 1995), in verbal inflections (Calabrese 2002)).

1. Distributed Morphology

The theory of Distributed Morphology (Embick 2010; Embick and Marantz

2008; Halle and Marantz 1993; Harley and Noyer 1999, among others) proposes

a piece-based view of word formation in which the syntax/morphology interface is

as transparent as possible. Distributed Morphology posits that there are two types

of primitive elements in the grammar that serve as the terminals of the syntactic

derivation, and, accordingly, as the primitives of word formation. These two types

of terminals correspond to the standard distinction between functional and lexical

categories (Embick and Halle 2005):6)

(8) a. Abstract Morphemes: These are composed exclusively of nonphonetic features, such

as [past] or [pl], the features that make up the terminal nodes of the syntax.

6) Abstract morphemes receive phonological features, i.e., exponents, by Vocabulary Insertion in

the morphological component (see below). Roots, instead, already have exponents and therefore

do not undergo Vocabulary Insertion. However, Root suppletion (see section 8 for an example)

is usually accounted for by assuming that suppletive roots undergo Vocabulary Insertion (see

Bobaljik 2012 for recent discussion). Some models of DM (see Marantz 1995) assume that all

roots undergo Vocabulary Insertion like abstract morphemes. The issue of whether or not roots

undergo Vocabulary insertion is not relevant for the analysis developed in this paper and will not

8 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

b. Roots: These make up the open-class vocabulary. They include items such as the

verbal roots /ven/, /mett/, /prend/, etc., which are sequences of complexes of phonetic

features, along with abstract indices (to distinguish homophones) and other diacritics

(e.g., class features).

Distributed Morphology conceives of the architecture of the grammar as sketched

in (9), in which Morphology refers to a sequence of operations that apply during the

PF derivation, operations that apply to the output of the syntactic derivation. This

theory is in its essence a syntactic theory of morphology, where the basic building

blocks of both syntax and morphology are the primitives in (8). There is no Lexicon

distinct from the syntax where word formation takes place; rather, the default case is

one in which morphological structure simply is syntactic structure.

(9) The Grammar

(Syntactic Derivation)

|

Morphology

PF

LF

The derivation of all forms takes place in accordance with the architecture in (9).

Roots and abstract morphemes are combined into larger syntactic objects, which are

moved when necessary (Merge, Move).

The Latin verbal form in (10) illustrates how a complex verbal form is derived.

This form has the syntactic structure in (11), where as proposed by Oltra-Massuet

(1999), Oltra-Massuet and Arregi (2005), Embick and Halle (2005), every functional/lexical projection has a Thematic Vowel. Thematic Vowels (TV) are special morphological elements adjoined to certain functional heads in morphological structure.

be discussed further here.

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 9

(10) laud - a: + u-i + s + s-e: + mus

‘praised-Perf-Past-Subj-1st Pl’

|

(11)

|

MOOD

|

V7)

|

√Root

laud

V

|

|

ASP

|

|

MOOD

T

|

| ASP | T

TV ASP

|

|

T

|

|

AGR

|

|

MOOD

MOOD

TV

TV

TV

Structures like those in (12) determine the terminal nodes to which phonological

realization is provided by the vocabulary items. Each terminal node consists of syntactico-semantic features drawn from the set made available by Universal Grammar.

In the simplest case, Morphology linearizes the hierarchical structure generated by

the syntax by adding phonological material to the abstract morphemes in a process

called Vocabulary Insertion. Therefore, the (abstract) morphosyntactic representation

is the input to a morphological component that assigns phonological realizations

to the terminal nodes (Late Insertion). During Vocabulary Insertion, individual

7) I assume, following Marantz (1997, 1999), that roots have no category and that in the syntax, they

are merged with category-giving functional heads. In the verbal domain, this head is v (Harley

1995; Chomsky 1995). This head is responsible for the verbal properties of the verbal complex.

In nonverbal environments, this head is n for nouns and a for adjectives (see Marantz 1999;

McGinnis 2000).

(i)

V

/ \

Root v

N

/ \

Root

n

A

/ \

Root a

However, as discussed by Embick (2010, 2011), this category-giving functional head, especially if

phonologically empty as in all of the cases discussed in this paper, is systematically transparent to

Vocabulary insertion and Readjustment rules—perhaps it is automatically pruned away once the

lexical category cycle (V/N/A) cycle has run through; it therefore does not play any role in defining

adjacency or locality for them. For this reason and also for the sake of representational simplicity I

will omit these functional heads in the morphosyntactic representation of verbal form in this paper.

10 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

Vocabulary Items—rules that match a phonological exponent with a morphosyntactic

context—are consulted, and the most specific rule that can apply to an abstract morpheme applies (in the so-called Elsewhere (Subset, Paninian) ordering). Vocabulary

Items are essentially instructions that insert phonological material in a terminal node

given certain specific feature configurations in the terminal node and its adjacent

environment. Abstract morphemes are thus said to be spelled out during Vocabulary

Insertion.

Thus, morphological pieces such as those in (11) are filled in by exponents via the

Vocabulary Items in (12):8)

(12) a. Root:

Laud

Vocabulary items:

TV

TV

TV

TV

b. [+perf]

[+past]

[+subj]

↔

↔

↔

c. [+auth, +part, +pl.]

↔

↔

↔

↔

a/

i/

Ø/

e/

v

s

s

/ [+past] ___

Root V____

[+perf]___

[+past] ___

[+subj] ___

↔

mus

8) The person features I adopt in this paper are given in (i):

(i) Person Features (see Bobaljik 2008 for a different system of person features)

2nd

3rd

1st

Author of speech act

+

Participant of speech act

+

+

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 11

(13)

MOOD

MOOD

|

V

|

√Root

laud

V

ASP

|

ASP

|

|

TV ASP

| |

a

v

|

|

TV

|

i

T

|

T

|

|

AGR

|

T

TV

s

Ø

| |

|

| ||

MOOD

|

MOOD

s

|

TV

e

mus

Vocabulary Insertion proceeds cyclically from the inside out, beginning with the

root node: Inner nodes can’t see outer nodes’ phonology, but outer nodes can see all

the features of inner nodes. (Halle and Marantz 1993; Bobaljik 2000; Embick 2010).

In addition, it is assumed that morphological operations operate under strict conditions of Locality; in certain configurations, a trigger of a given rule may be too far

away to trigger that rule.

Notice at this point that the phonological information contained in the exponents inserted by Vocabulary Items is not sufficient to ensure that in all cases the

correct phonological output will be generated. In addition to the Vocabulary Items,

a number of further rules that alter the phonology of the exponents are required.

Such rules are called Readjustment Rules in Distributed Morphology. Readjustment

Rules are phonological rules. Their distinguishing property is, however, that they are

conditioned by both morphosyntactic and Root/morpheme-specific information. In

this way, Readjustment Rules differ from other rules of the phonology that require

no reference to morphosyntactic environments; nor to diacritics specifying whether a

given root/morpheme undergoes or triggers them.

An example of a Readjustment Rule applying in the Passato Remoto of irregular

12 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

verbs is the rule that changes the quality of the root vowel in a form such as 3rd pl.

videro (cf. vedesti 2nd pl) ‘see’. The rule is given in (14). Crucially this must be restricted to apply to the root vowel of roots such ved ‘see’, met ‘put’, fond ‘fuse’ which will

be marked by a special diacritic (see section 6 for discussion of the use of diacritics):

(14)

N

|

X

[-cons] → [+high] / ___ C]Rooti ^ Past

(e, o → i, u)

Rooti = ved, mett, fond

Locality will be of particular importance in the analysis developed here. An important issue is how locality is defined. Nevins (2010), along the lines of Rizzi (1990,

2001), proposes that Locality is not absolute but must always be relativized according

to some given parameter that establishes what is relevant in defining it. I adopt this

idea here. An example can be provided by long distance operations in Phonology

when analyzed in terms of Visibility theory (Calabrese 2005).9) According to this

theory, processes in search of a target may disregard/“not see” certain sets of features,

specifically non-contrastive or unmarked features, and achieve locality in this way.

Consider lateral dissimilation in Latin. According to this process, the /l/ of the suffix

/-alis/ dissimilates to /r/ when preceded by another /l/ (cf. semin-alis vs. aliment-aris

unless an /r/ intervenes between them (cf. littor-alis). The rule is defined as operating

only on contrastive specification for [lateral]. Therefore, the non-contrastive [-lateral]

specifications of non-sonorant or nasal consonants are disregarded by the process (cf.

aliment-aris, milit-aris). We can then say that the process applies locally between the

contrastive feature specifications [+lateral] on the lateral plane disregarding the non-

9) Visibility theory proposes an alternative account for facts that were previously accounted for in

phonology by assuming feature underspecification. Feature underspecification has been shown to

lead to various problems and has been abandoned in recent models of phonology (see Clements

2001; Calabrese 2005; Dresher 2009; Mohanan 1991; Nevins 2010, among others for discussion).

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 13

contrastive specifications [-lateral] (those of [m], [n] and [t]) which are shaded in (16)

and (17).

(15) [+lateral] > [-lateral] / [+lateral] ___ in the suffix -alis

(Parameter: Access only contrastive features.)

(16) a l i m e n t -a l i s > (by (15)) > a l i m e n t -a r i s

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

+lat -lat -lat -lat +lat

+lat -lat -lat -lat -lat

However, if the contrastive specification [-lateral] intervenes between them, the process can no longer apply.

(17) l i tt o r - a l i s

|

| | |

+lat -lat -lat +lat

Morphological operations can be defined in the same way so that certain aspects of

the morphological representations may be disregarded to achieve locality. The obvious question is that of the parameters governing locality in morphological operations.

In this paper I will focus on a basic parameter that appears to be governing morphological operations: featural locality vs. linear adjacency, and I will not investigate

other additional parameters that may intervene.

Morphemes have a bipartite structure in which a phonetic index—an exponent—is associated with a set of morphological (syntactic/semantic/lexical) features.

Morphological rules, then, may refer to these two components of the morphemes:

the features or the exponents. Different definitions of locality follow from this. I propose that there are rules that look at the featural organization of the string, and others

that look at the string’s composition in terms of exponents.10) The latter rules require

10) If one assumes that this holds only for overt exponents, morphemes with null, non-overt exponents will be disregarded by rules of this type.

14 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

surface linear adjacency as a condition for their application; the former look only for

adjacency between feature containing nodes or, better, between nodes containing

relevant features. These rules may disregard surface exponents lacking features or,

better, relevant features.

The Vocabulary Insertion Rules characterizing irregular morphology in the

Passato Remoto are a clear instance of rules requiring linear adjacency: as we will

see, they apply only if there is this type of adjacency between the location of their

application and the irregular root. If this adjacency is disrupted by the presence of a

Thematic Vowel, only regular unmarked morphology will occur. For example, the

special exponent /-s-/ for the[+past]Tense of some of the irregular Passato Remoto

forms is inserted by the Vocabulary Item in (18). This rule applies only when Tense

is linearly adjacent to the Root (Remember that this requirement is represented here

by the symbol ^.):

(18) VI rule for the Passato Remoto Tense morpheme (provisional)

/s/ ↔ [+Past]T / Roots ^____ (where Roots = corr, val, perd, met, etc.)

Given the linear adjacency requirements, (18) can apply only when the Thematic

Vowel is missing. So it can apply in the structure in (19) but not in (20) where the

TV is present:

(19) a. [[[[ corrS ]root

b. [[[[ corrS ]root

c. cor-s-i

] +PAST TV ]T +part, -+auth, -pl] AGR

]

s

]T i ] AGR

(20) a. [[[[ corrS ]root TV] +PAST TV ]T +part, +auth, +sg] AGR

b. [[[[ scriv ]root e]

s

]T i ] AGR

c. corr-e-s-i

A different type of vocabulary insertion rule is found in the case of the Latin Perfect

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 15

AGR suffix. Embick (2011) shows that the special perfect 2nd sg. AGR ending /-sti/

of Latin appears only when no other Tense or Mood morpheme appears between

AGR and [perf] Aspect. Otherwise, as can be seen in (21), the Agreement morphemes are those found elsewhere in the system (i.e., /-s/↔2s):

(21) amā-v-i-stī vs. amā-v-e-rā-s, amā-v-e-rĭ-s, amā-v-i-s-s-e-s ‘love-2Sg.’

Perf. Ind. Pluperf. Ind.

Perf. Subj. Pluperf. Subj.

Cf. amā-s amā-b-ā-s

‘love-2Sg.’

Pres. Ind.

Imperf. Ind.

The problem is that a theme vowel /-i-/ appears between the Perfect and AGR.

Therefore there is no linear adjacency between these morphemes. I propose that in

this case the Vocabulary Item is inserted by looking at the closest relevant feature

without requiring linear adjacency:

(22) /-stis / ↔ 2p / [perf.] __

In the form /amā-v-i-stī/, the feature [Perfect] is the closest feature to AGR insofar as

the Theme vowel does not contain any features. Locality is therefore met although

not in terms of linear adjacency.

We can now turn to the issue of allomorphy generated by Readjustment Rules. As

discussed below, the Readjustment Rules accounting for the allomorphy we observe

in the Passato Remoto obey linear adjacency. But this is only one of the parametric

options available for morphological rules. So there can be Readjustment Rules that

obey a different type of locality. In fact, Embick (2010, 2011), following Kiparsky

(1996), provides examples of Readjustment Rules that do not appear to obey linear

adjacency. An example is metaphony in Italian dialects:

16 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(23) Metaphony triggered by AGR in the dialect of Ischia, Campania

Pr. ind.

Impf. ind.

1s kand-ə

kand-a-v-ə

‘sing’

2s kɛnd-ə

kand-ɛ-v-ə

3s kand-ə

kand-a-v-ə

The most adequate analysis of these alternations involves a Readjustment Rule

raising the stressed vowel triggered by 2nd sg. AGR, which is realized as [ə] as the

other AGR suffixes. The rule is fully morphologized in also having exceptions and

lexical conditioning. However, this readjustment rule applies over intervening

Imperfective tense morpheme -v in kand-ɛ-v-ə (Root-TV-T-AGR). Nonetheless,

although this rule violates linear adjacency, it can still be considered as applying

locally if we see locality in relativized terms. The point is that the metaphony rule

must be defined as applying to a stressed vowel. If we assume that the target of

metaphony must be contained in the “closest” morpheme that satisfies the rule

description, we have a simple account for how adjacency is violated. The “intervening” morpheme here contains only a consonant which is not a possible target of metaphony. Therefore, this morpheme can be disregarded.11) If a morpheme contains a

vowel, it cannot be skipped. Another similar case reported in the literature is from Zulu, where the palatalization of labial consonants triggered by the passive suffix -w skips the intervening causative morpheme -is (Carstairs 1987; Carstairs-McCarthy 1992):

11) If we look at the rule from the point of view of the trigger, one can say that morphological

rules apply to the ‘closest’ morpheme that can undergo the rule. If, on the contrary, we look at the

rule from the point of view of the target, the rule is triggered by the closest morpheme that contains a possible trigger. Therefore in a situation like that in (i):

(i) target(m)-X-trigger(m)

trigger-target interactions are possible only when X is neither a possible undergoer nor a trigger.

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 17

(24) Zulu palatalization of labials

Active

a. bamb-a ‘catch’

boph-a ‘tie’

b. bamb-is-a ‘cause to catch’

boph-is-a ‘cause to tie’

Passive

banj-wa ‘be caught’

bosh-wa ‘be tied’

banj-is-wa ‘be caused to catch’

bosh-is-wa ‘be caused to tie’

The idea proposed above can be easily extended to this case once we observe that the

target can only be a labial consonant. Therefore, the Readjustment Rule of Zulu targets the closest morpheme containing a labial.

The Italian Passato Remoto rules are not of this type, though. They indeed require

linear adjacency. As discussed above, this follows from a different parametric choice:

These rules are defined as requiring linear adjacency. Given this requirement, an

intervening TV blocks their application.

It is an open question whether or not there are principled reasons for the selection

of the different parametric choices defining locality in allomorphic processes. I do not

believe so. As in the case of the different parametric options defining locality in the

case of phonologic rules, I have the feeling that the different choices may have their

causes in diachronic idiosyncracies. Further research must establish if this is indeed

correct and investigate what happens in the historical development of these processes.

2. Basic Properties of Italian Verbal Morphosyntax

The basic morphosyntactic structure of Italian verbs is given in (25):12)

12) A morphosyntactic change occurred in the development of the Romance languages as can be seen

in (i) where I compare the Latin pluperfect subjunctive in (ia) (= (11)) with the form that historically derived from it in Italian, i.e., the Imperfect subjunctive (ib):

18 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(25)

T

V

T

T

|

T

ROOT

AGR

The structure in (25) then undergoes Thematic Vowel insertion. Thematic Vowels

are adjoined to V and Tense heads as in (26):

(26)

T

V

T

|

V

|

TV1

ROOT

T

T

AGR

TV2

(26) accounts for the morphological structure of the imperfect forms in (27) (and for

the imperfect subjunctive in (23b)).

(i)

a. laud - a: + u-i

+s

b. lod -a+ss-i-

+ s-e:

+ mus

+ mo

‘praise-PlprfSubj1pl’

‘praise-ImpSubj1pl’

In Italian, functional categories such as aspect, tense and mood are no longer represented as

independent morphological pieces as they were in Latin. Instead, a single morpheme appears in

their place. This morphosyntactic development and its semantic consequences are irrelevant to

my analysis here. I will simply assume that the Asp, Tense and Mood nodes are fused together in

Italian (i.e., Tense in (25) = Aspect+Tense+Mood). Another issue that I will put aside is whether or

not V-to-V movement is needed to derive (25).

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 19

(27) Italian imperfect indicative

AMARE ‘love’:

am-a-v-o am-a-v-i am-a-v-a

BATTERE ‘beat’:

batt-e-v-o batt-e-v-i batt-e-v-a

PARTIRE ‘leave’:

part-i-v-o part-i-v-i part-i-v-a

1

2

3

Singular

am-a-v-a-mo am-a-v-a-te am-a-v-a-no

batt-e-v-a-mo batt-e-v-a-te batt-e-v-a-no

part-i-v-a-mo part-i-v-a-te part-i-v-a-no

1

2

3

Plural

In the Present Tense (see (28)), there is no evidence for an independent Tense morpheme. The same situation is found in Spanish, and to account for this fact, OltraMassuet and Arregi (2005) propose a process of fusion merging Tense and AGR into

a single node. I propose that the same process of fusion applies in Italian, changing

(25) into (29):

(28) Italian present indicative

AMARE ‘love’:

am-o am-i am-a BATTERE ‘beat’:

batt-o batt-i batt-e PARTIRE ‘leave’:

part-o

part-i part-e 1

2

3

Singular

am-ia-mo am-a-te am-a-no

batt-ia-mo batt-e-te batt-o-no

part-ia-mo 1

Plural

part-i-te 2

part-o-no

3

(29) Fusion between Tense and AGR:

T

V

|

V

|

ROOT

TV

20 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

T

|

T+ AGR

Observe that the Fusion process must apply before the insertion of the Tense

Thematic Vowel, otherwise the Thematic Vowel position would interfere with the

fusion process. Furthermore, as discussed later at the end of section 3, a cyclic implementation of fusion and TV insertion appears to be required.

The following vocabulary items account for verbal inflections in the Italian present

and imperfect tenses of regular verbs. In the case of the Vocabulary Items in (30) the

Head can include a root or the head of a functional projection (cf. (32)):

(30) TV13)

→

(31) AGR Suffixes:

a. /-mo/

b. /-te/

c. /-no/

d. /-o/

e. /-i/

f. /Ø/

↔

↔

↔

↔

↔

↔

/-a-/

/-e-/

/-i-/

Head a ____

Head e ____

Head i ____

[+author, +plural]AGR

[+participant, +plural]AGR

[+plural]AGR

[+author]AGR / [-subjunctive]T _____

[+participant]AGR / [-subjunctive]T _____

[-participant]AGR

13) According to (30) we should expect the forms in (i) for the 1st pl. present of all conjugations and

the 3rd pl. present of the /e/ and /i/ conjugations:

(i) a. am-a-mo

b.

batt-e-mo part-i-mo

batt-e-no part-i-no

We instead have the forms in (ii):

(ii) a. am-ya-mo batt-ya-mo par-ya-mo

b.

batt-o-no part-o-no

Further vocabulary items accounting for the surface form of the Thematic Vowels we see in (ii) are

given in (iii) and (iv).

(iii) TV ↔ ya / [ ___ ]TV^[PRES, +part, +auth, +pl]AGR+T

(TV is [ya] in the 1st pl. of present tense of all conjugation.)

(iv) TV ↔ o / Roote & i [ ___ ]TV ^[PRES, -part, -auth, +pl]AGR+T

(TV is [o] in the 3rd pl. of present tense of II and III conjugation.)

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 21

(32) Tense Exponents (the subscript a indicates that the imperfect Thematic Vowel is /a/ by

(30)) :

/-v a -/

↔

[+imperfect]tense

A phonological rule that is very important in accounting for the surface distribution

of the Thematic Vowels is that in (33) which deletes Thematic Vowels before vowelinitial suffixes. Sample applications of this rule are given in (34). Given rule (33) the

verb, Thematic Vowel in the present indicative and the Tense Thematic Vowel in

the imperfect indicative are deleted before the suffix /-o/.

(33) V

→

Ø / [TV ___ ] + [V

(34) [[[am]-a]-o]

[[[[am]-a]-v-a-o]

→

→

amo

amavo

‘love-PresInd-1sg.’

‘love-ImperfInd-1sg.’

3. The Passato Remoto Forms of Regular Verbs

Before dealing with the allomorphy characterizing the irregular forms of the

Passato Remoto let us consider the regular forms of this tense in Italian.

22 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(35) Passato Remoto of Regular Verbs

AMARE ‘love’:

am-a-i14) am-a-sti am-ò

BATTERE ‘beat’:

batt-e-i batt-e-sti batt-è

PARTIRE ‘leave’:

part-i-i part-i-sti part-ì

TEMERE ‘be afraid’

tem-e-i tem-e-sti tem-è

1

2

3

Singular

am-a-mmo

am-a-ste am-a-ro-no

batt-e-mmo

batt-e-ste batt-e-ro-no

part-i-mmo

part-i-ste part-i-ro-no

tem-e-mmo

1

Plural

tem-e-ste 2

tem-e-ro-no

3

If we compare the regular forms of the Passato Remoto in (35) to those of the indicative present (28) and the imperfect (27), this Tense appears to have only 3 different

pieces like the present, not 5 like the imperfect (see (26)). One could assume a null

exponent for Tense as in (36):

(36) [[[[part]root i]V -Ø-]T ste]AGR

But in the structure in (36) we would also expect to find a Tense Thematic Vowel.

However, it is missing. The best account for this fact is to assume that the regular

forms of the Passato Remoto do not have the structure in (26) but actually that in

(29), repeated here as (38), as in the Present. Therefore, also in the Passato Remoto

of the regular verbs, Tense and AGR undergo fusion (see Oltra-Massuet and Arregi

2005 for a similar proposal for Spanish):

(37) a. tem-e-ste

b. tem-e-te

c. tem-e-v-a-te

14) The 1st sg. of the Passato Remoto displays a systematic exception to (33). In this person, the verb’s

Thematic Vowel is never deleted before the following vowel initial suffix /-i/. Rule (33) applies as

usual in the 3rd sg. (am-a-ò → am-ò).

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 23

(38)

T

V

|

V

|

ROOT

T

|

T+ AGR

TV1

This analysis accounts for the fact that neither a tense morpheme nor a related

Thematic Vowel are present in the regular forms of the Passato Remoto. Evidence

for this analysis is provided by the distributional properties of AGR suffixes. Notice

that the other past forms in the verb conjugation share AGR suffixes that are different from those found in the regular forms of the Passato Remoto (35). Consider for

example the 3rd sg. and pl. of the imperfect subjunctive and of the conditional where

we have the suffixes: /-e/, /-e-ro/:

(39) Imperfect Subjunctive

am-a-ss-e

‘love-3sg.’

am-a-ss-e-ro

‘love-3pl.’

(40) Conditional

am-er-ebb-e

am-er-ebb-e-ro

These suffixes also appear in the irregular forms of the Passato Remoto:

(41) venn-e

venn-e-ro

‘come-3sg’

‘come-3pl’

The non-appearance of these suffixes in the regular forms of the Passato Remoto can

be accounted for by saying that the suffixes found in the regular forms have a more

restricted distribution than those found in (39), (40) and (41). In fact, notice that

24 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

some of these suffixes require Thematic Vowel information like the 3rdsg. /-ò/ of the

/-a/-conjugation, (the so-called 1st conjugation), the 3rd sg. preaccenting /-Ø/ of the

/e/ and /i/-conjugations (the 2nd and 3rd conjugations), and also the augment /no/ for

the 3rd plural which appears only in the Passato Remoto of the regular verbs. Now, if

we assume the locality requirement—in any of its forms: either linear or featural adjacency—for morpheme-morpheme interactions, access to Thematic Vowel information would be impossible for a Vocabulary Item realizing AGR since the Tense node,

which contains a relevant [+past] feature, intervenes between them. However, if we

assume fusion between Tense and AGR, adjacency between the insertion site of the

special Vocabulary Items and the Thematic Vowel is achieved. Therefore, the presence of special suffixes requiring Thematic Vowel information in the regular forms

of the Passato Remoto provides independent evidence for the fusion between Tense

and AGR in (38).

The vocabulary items for the AGR terminal node are given in (42). Notice that,

in the 3rd sg. of the irregular forms, one finds the 3rd person exponent /Ø/ in (31f),

which is also characteristic of other tenses. I assume that the ending /-e/ we see in

(41) is actually the Tense Thematic Vowel (see (44) below). The symbol ] appearing

in (42) is a prosodic bracket causing stress assignment on the suffix (i.e., amò ‘lovePast-3rd sg’) or on the preceding TV (battè ‘beat-Past-3rd sg’, temè ‘fear-Past-3rd’, partì

‘leave-Past-3rd’) (see section 5 for discussion of the stress algorithm in Italian verbs).

The rules in (42a-b) apply only in regular morphology. This is indicated by the context TVa ]V_____ (The presence of the Thematic Vowel is in fact the characterizing

feature of regular morphology, as discussed above.). The other rules apply to all verbs:

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 25

(42) VIs for the AGR morpheme

]

a. /-o/

↔ [-part, +past]T+AGR / TVa ]V^ _____

]

b. /-Ø /

↔ [-part, +past]T+AGR / TV] V^ _____

c. /-mmo/ ↔ [+author, +plural]/ [+past] ____

d. /-ste/

↔ [+participant, +plural]/ [ +past] ____

e. /-sti/

↔ [+participant, -author]/ [ +past] _____

f. /-i/

↔ [+author]/ [+past] _____

g. /-ro/

↔ [-participant, +plural]/ [+past] _____

The suffix /-no/ that appears in the 3rd pl. of regular Passato Remoto forms is

accounted for in the following way: there is fission of [+plural] in [-part, +plural,

+past] in the context TV]V___; then application of (30c) leads to the insertion of

/-no/ (see Halle 1997; Noyer 1992 on morphological fission).

Above, I proposed that in the Passato Remoto of the regular verbs Tense and

AGR undergo fusion like in the present, as in (38), to account for the fact that no

overt tense morpheme appears in them. However, unlike the regular forms of the

Passato Remoto, irregular forms—which are athematic, as discussed below—do

show such an overt morpheme for this tense. In fact, forms like those in (43) argue

for a morphological segmentation in which /s/ is the exponent of the Past with the

additional application of the Readjustment Rules discussed in section 6.

(43) val-e

ett∫ɛll-e korr-e

speɲɲ-e

pɛrd-e

voldʒ-e

val-s-e

ett∫ɛll-s-e [ett∫ɛlse]

korr-s-e [korse]

speɲɲ-s-e [spese]

perd-s-e [perse]

voldʒ-s-e [volse]

‘be worth’

‘excel’

‘run’

‘turn off’

‘lose’

‘turn’

I assume that these forms have the constituent structure in (44) (after Verb TV pruning (see below)):

26 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(44)

T

T

T

V

|

ROOT

korr

(cf. korr

T

TV

s

s

e

e

|

|

AGR

|

Ø (3rd sg.)

ro (3rd pl.))

The crucial aspect of the structure in (44) is the absence of the Verb Thematic

Vowel. Hence I propose that the Tense+AGR fusion is restricted to Thematic constructions as in (45):15)

(45) T

|

+past

AGR

→

T+AGR

|

+past

/

TV]V

______

Notice that once we assume the structure in (44), we have an account for why the

default AGR suffix /Ø-/ (31f) appears in the 3rd sg. As mentioned above, the special

items listed in (42a) appears only when linearly adjacent to the verb Thematic Vowel

(am-a-ò (surface am-ò)), and therefore not to the Tense Thematic Vowel, like the

AGR suffix in (31f).

The Vocabulary Item for the Passato Remoto forms in (44) is given in (46); other

two VIs will be discussed later. The reasons for having a diacritic index on the root

will become clear in section 6.

15) It follows that Fusion in (45) must apply after TV pruning in (49) which I assume to be a readjustment rule. A consequence of this is that (45) should also be considered a Readjustment Rule.

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 27

(46) VI for the Passato Remoto Tense morpheme (provisional)

/s/ ↔ [+Past]T / Roots^ ____ (where Roots = corr, val, perd, met, etc.)

I will close this section by turning again to the relative ordering of Fusion and

Thematic Vowel insertion. It is obvious that the Fusion process must apply before

the insertion of the Tense Thematic Vowel: otherwise the TV would prevent the

fusion process. However, as proposed above, the presence of the Root TV is crucial

for the application of Fusion in the past. This calls for a cyclic implementation of TV

insertion and fusion: first, at the root node a TV is appended, and then (39) applies

at the root node (if its conditions are met, i.e., the presence of a special diacritic index

(see section 4). Then, on the next cycle (Tense) either Fusion applies, or, if its conditions are not met, then TV is appended to (unfused) Tense.

4. The Passato Remoto Forms of Irregular Verbs

Let us turn to the irregular forms of the Passato Remoto. Sample cases are given in

(47):

(47) Singular

1

valsi

persi

misi

scrissi

fusi

venni

takkwi

2

valeste

perdesti

mettesti

scrivesti

fondesti

venisti

tat∫esti

3

valse

perse

mise

scrisse

fuse

venne

takkwe

Plural

1

valemmo

perdemmo

mettemmo

scrivemmo

fondemmo

venimmo

tat∫emmo

2

valeste

perdeste

metteste

scriveste

fondeste

veniste

tat∫este

3

valsero

persero

misero

scrissero

fusero

vennero

takkwerò

‘be worth’

‘lose’

‘put’

‘write’

‘fuse’

‘come’

‘be silent’

As observed earlier, if we look at the paradigm in (47) a striking regularity can be

28 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

observed. In the 1st and 3rd sg. and 3rd pl., we have an athematic form of the verb and

the root appears in an idiosyncratic irregular form. In the 1st and 2nd pl. and 2nd sg.,

there is a thematic form of the verb and the form of the root regularly appearing with

other tenses is found.

I will account for the alternations between the athematic and thematic forms in

(47) in section 6. For now, let us consider the phonological changes affecting the

athematic forms of the verbs. The first issue to address is the absence of Thematic

Vowels in these verbs. We saw that the irregular forms of the Passato Remoto are

athematic:

(48) Regular

[[[batt]V -e]TV-i]T+AGR

vs.

Irregular16)

[[[corr]V -s]T -i]AGR / [[[perd]V-s]T -i]AGR

The absence of the Thematic Vowel is accounted for by a rule of pruning in (49).

Rule (49) removes the Thematic Vowel after certain roots, those that have irregular

forms in the past. I propose that these roots are assigned a special diacritic [+TV-pruning].

The reason for assuming a special diacritic index for these roots will be discussed in

section 6. Observe that only roots of the e- and i- conjugations undergo Thematic

Vowel Pruning. Given that the rule in (49) is sensitive to root-specific information, I

assume it to be a Readjustment Rule:

(49)

V

V

TV / Root-e/i[+TV-pruning]^___ Past, Root[+TV-pruning]= korr, prend, met, ven, etc.

Thus given (50), we obtain (51) due to the application of (49):

16) Actually, the forms below contain an underlying Tense Thematic Vowel that is deleted before the

suffixal V by (33): [[[corr]V -s-e-]T -i]AGR / [[[perd]V-s-e-]T -i]AGR. Remember that the 1st sg. of the

regular Passato Remoto is an exception to rule (33).

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 29

(50)

|

V

|

V

|

ROOT[+TV-prn]

(51)

T

|

TV1

T

|

|

T

|

AGR

T

T

T

| |

AGR

V

|

ROOT[+TV-prn]

In addition to being athematic, however, irregular verbs undergo various phonological changes. For example, coronal [+anterior] stops /t, d/ and /n/ are deleted

before /s/. This accounts for metteva/mise (root: mett ‘put’), kyudeva/kyuse (root: kyud

‘know’), utt∫ideva/utt∫ise (root: utt∫id ‘kill’). Another rule that is crucial to account

for the allomorphy we see in the irregular past forms is the rule of /s/- assimilation.

It applies to obstruents (both stops and fricatives) and to nasals but not to liquids:

condut∫eva/condusse (root: konduk ‘conduct’), skonfiddʒeva/skonfisse (root: skonfigg

‘defeat’), diridʒeva/dirisse (root: dirig ‘direct’), komprimeva/comprɛsse (root: komprim

‘compress’), kwɔtƒeva/kɔsse (root: kwɔt∫ ‘cook’), mwɔveva/mosse (root: mwɔv ‘move’),

viveva/visse (root: viv ‘live’), skriveva/skrisse (root: skriv ‘write’). Another rule deletes

the root nasal in the Passato Remoto: rompeva/ruppe, interrompeva/interruppe. Other

rules change the quality of the root vowel: fat∫eva/fet∫e, vedeva/vide, rompeva/ruppe.

In Calabrese (2012), I provide a detailed account of these rules and how they apply.

Here, I will focus only on another change characterizing the irregular morphology:

30 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

gemination. Consider sample forms like those in (52):

(52) Imperf.

vɛniva

kadeva

voleva

not∫eva

tat∫eva

Passato Remoto

vɛnne kadde

volle

nokkwe

takkwe

Root

vɛn

kad

vol

nok

tak

‘come’

‘fall’

‘want’

‘harm’

‘be silent’

Notice that the gemination of the final consonant in these forms indicates the

presence of an extra skeletal position. The rounding observed on the velar stop in

takkwe, nokkwe also indicates the presence of a labial [+round] feature that is otherwise

lost. To account for the gemination we observe in these forms, I propose to postulate

the exponent in (53a) for the Passato Remoto in addition to that already mentioned

in (46) (= (53b)). Another exponent of the Passato remote is /Ø/ which is inserted by

(53c) after the roots /fak/ ‘do’ (fet∫ -Ø- i) ‘I did’ and /ved/ ‘see’ (vid-Ø-i ‘I saw’).

(53) a. X ↔ [+past]T / RootL ^____ (RootL = nok, tak, dʒak, etc.)

|

Labial

|

[+round]

b. s

↔ [+past]T / RootS ^ ____ {RootS= scriv, muov, etc.}

c. Ø ↔ [+past]T / RootØ ^ ____ {RootØ= fak, ved, etc.}

(53a) consists of an empty skeletal position including, however, a floating nondesignated labial [+round] articulator, a secondary articulation (see Halle 1995 for

the notion of designated articulator). The skeletal position is filled in by the preceding consonant. The secondary labial articulation is attached to the place node only

when the designated articulator of the first consonant is dorsal, otherwise its attachment is blocked because of an active Marking Statement disallowing labial secondary

articulation with non-dorsal consonants. In this case, the secondary articulation is

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 31

deleted.17)

(54) v e n

XXX

|

-

i

-X

X

[+cons]

|

Place

|

=

Coronal

|

|

→

|

-

X

[+cons]

|

Place

|

Dorsal

|

[+dorsal]

|

|

Labial

|

[+round]

[+cons]

|

Place

|

Coronal

|

[+coronal]

i

-X

tak

XXX

[+coronal]

[+anterior]

[+distributed]

(55) t a k

XXX

ven

XXX

→

|

|

n

-X

i

-X

Labial →Ø

|

[+round]

kw

- X

i

-X

[+cons]

|

Place

|

Labial

|

[+round]

Dorsal

|

[+dorsal]

Labial

|

[+round]

17) The Passato Remoto of the irregular verb parere ‘seem’ seems to require the postulation of an

additional exponent /-v-/ in addition to those listed in (53) (cf. 3rd pl. parvero /par-v-e-ro/ (vs. 2nd

pl. par-e-ste). This exponent would be restricted only to this verb. Here I prefer to assume in the

case of this form that we are dealing with an instance of the exponent in (53a) which after the root

/par/ undergoes the special readjustment rule in (i) assigning features such as [+consonantal, -sonorant, +cont] to the empty skeletal position characterizing this exponent. The feature [+round] is

deleted because of the restriction of [+round] to dorsal stop consonants:

(i)

X

→

[

Labial

|

[+round]

32 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

X

/ par ^ ____

|

+cons

-son

|

Labial [+cont]

]

|

[+round]

Derivations for the 3rdpl. forms in (47) are given in (56):

(56) Rules:

Thematic Vowel Deletion (TV): (49)

Ablaut Rules (A) changing root vowel quality

Coronal Stop Deletion (CD)

Consonantal Assimilation (CA)

Nasal Deletion (ND)

a.

TV

VI

Output:

b.

TV

VI

CD

Output:

c.

TV

VI

A

CD

CD

Output:

d.

TV

VI

CA

Output:

e.

TV

VI

A

CD

ND

Output:

[[[[ val ]root TV] +PAST TV ]T -part, +pl ] AGR

[[[[ val ]root ] +PAST TV ]T +part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ val ]root ]

s e ]T ro

] AGR

valsero

[[[[ perd]root TV] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ perd ]root ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ perd ]root ] s

e ]T ro

] AGR

per

s

e ro

persero

[[[[ mett ]root TV] +PAST TV ]T +-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ mett ]root ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl ] AGR

[[[[ mett ]root ]

s

e ]T ro

] AGR

mitt

s

e

ro

mit

s

e

ro

mi

s

e

ro

misero

[[[[ skriv]root TV] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ skriv ]root ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[skriv ]root ]

s

e ]T ro

] AGR

skris

s

e

ro

skrissero

[[[[ fond]root TV] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ fond ]root ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ fond ]root ]

s

e ]T ro

] AGR

fund

s

e ro

fun

s

e ro

fu

s

e ro

fusero

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 33

f.

[[[[ ven ]root TV ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ ven ]root

] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

[[[[ ven ]root

] Xw e ]T ro

] AGR

w

venn

e

ro

venn

e

ro

vennero

g.

[[[[ tak ]root TV] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

TV

[[[[ tak ]root ] +PAST TV ]T-part, +pl] AGR

VI

[[[[ tak ]root ]

Xw e ]T ro

] AGR

w

Gemination takk

e ro

Output:

takkwero

TV

VI

Gemination

Derounding

Output:

5. Brief Discussion of Stress in Verbal Forms

The alternations in (47) are also associated with stress shifts. Most other accounts

of them—some which will be critiqued later—pay much attention to the stress patterns of the alternating forms. In this section, I briefly consider the stress properties

of the Passato Remoto. I argue that the position of stress simply follows from the

morphosyntactic structure of the verb forms. Therefore, it cannot have any role in

determining them.

Italian nouns display stress on any of the three final syllables. The stress falls on the

penultimate if it is heavy. Otherwise, it can occur either on the penultimate or the

antepenultimate. Here I assume that penultimate stress is lexically marked, and the

antepenultimate is the default. I will not deal with stress on nouns here.

In verbs, any of the last four syllables may be stressed, as shown in (57). If we

include forms with clitics we even find stress on the fifth-last syllable (see (57)).

34 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(57) a. Final syllable

auguró ‘s/he wished’

b. Penultimate syllable

auguráva ‘s/he was wishing’

c. Antepenultimate syllable

áuguro ‘I wish’

d. Preantepenultimate

áugurano ‘they wish’

áuguraglielo ‘Wish it to him/her!’

As observed by Oltra-Massuet and Arregi (2005), the morphosyntactic structure of

the verbal form is important to determine stress in Spanish and Catalan. Specifically,

according to Oltra-Massuet and Arregi, in these two languages stress falls on the

vowel preceding the Tense node, in particular on the verbal Thematic Vowel. Most

stress patterns in Italian verbs follow this generalization, as we can see in (58):

(58) Stress on the Thematic Vowel (in bold and underlined) before Tense

augurávo

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

augurávano

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

augurássi

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

However, there are some differences. First of all, in Italian the Thematic Vowel

immediately preceding the 1st and 2nd pl. suffix stress has a special status and always

receives stress so that in this case stress is shifted rightwards from the Thematic Vowel

before T. In Spanish this does not occur and stress always falls on the Thematic

Vowel before T (Spanish: cantábamos, cantábais ‘sing’ vs. Italian cantavàmo, cantavàte

‘sing’).18)

18) An exception is the imperfect subjunctive where stress falls on the verb Thematic Vowel and not

on the Thematic Vowel preceding the suffix of 1st:

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 35

(59) auguravàmo (cf. augurávo)

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

auguraváte

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

There is then another difference more complex to describe since it has to do with

exceptions to the generalization that stress is assigned to the V before Tense. In both

Spanish and Italian, present indicative and subjunctive forms, stress falls on the root

and not on the Thematic Vowel19),20) as would be expected given Oltra-Massuet and

Arregi’s generalization. Take for example the 3rd pl. cánten in Spanish. According to

this generalization, stress should be on the thematic /e/ as in cantén instead of being

on the root syllable. To account for this fact, Oltra-Massuet and Arregi propose

that there is a special rule that retracts stress from the final vowel onto the preceding

vowel. However, this account cannot hold in Italian due to the following: (i) the suffix of the 3rd plural in Italian ends in a vowel; the consequence of this is that we cannot use this retraction rule to account for the root stress in this person. (ii) In addition, if stress falls on the root in Italian and the root contains more than one syllable,

stress can be on the last root syllable as in (61), or crucially on the penultimate root

syllable as we can see in (60) and (61), although never on a syllable preceding this

one (see (62)). The retraction rule would always give stress on the last root syllable in

Italian, contrary to the facts.

(i)

augurássimo

19) One could hypothesize that this fact is related to the fusion between Tense and AGR in this tense:

namely, once Tense is fused with AGR, it is no longer a true Tense node, and one could hypothesize that only “true” Tense nodes can trigger stress assignment. However, this does not hold for

the regular forms of the Passato Remoto where we also have fusion between Tense and AGR but

Tense still assigns stress. This hypothesis must then be rejected and the rule must be formulated as

not applying in the present.

20) As mentioned earlier, the 1st and 2nd pl. behave differently and stress is assigned to the TV that

precedes the AGR suffix in this case.

36 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(60) Stress on the root

áuguro

[[ root TV] T + AGR ]

áugurano

[[ root TV] T + AGR ]

(61)

1sg

3sg

3pl

a.

prédico ‘preach’

prédica

prédicano

(62) teléfono ‘phone’

comúnico ‘communicate’

b.

adóro ‘worship’

adóra

adórano

télefono

cómunico

Note that regardless of the position of stress in the present, in the other tenses verbs

follow the preceding generalization: stress falls on the Thematic Vowel before Tense,

on the Thematic Vowel before 1st and 2nd pl., or on exceptional final endings, e.g.,

predicò (see below for discussion):

(63) predicáva, predicavámo, predicò

adorávo, adoravámo, adorò

‘preach-ImpInd-3sg./1pl./past-3sg.’

‘worship-ImpInd-3sg./1pl./past-3sg.’

I will simply propose that the rule assigning stress to the TV before Tense does not

apply in the present (see note 20). The default stress rule of Italian applies in this

case, assigning antepenultimate stress unless the penultimate vowel is heavy or is

assigned an idiosyncratic lexical accent: (prédic-o vs. adór-o). A detailed discussion

of Oltra-Massuet and Arregi’s analysis is not possible here due to space limits so I

will simply go on and propose a modification of Oltra-Massuet and Arregi’s theory

that can account for the Italian stress pattern. Following their lead, I assume an

account within the framework of the metrical grid (see, e.g., Liberman and Prince

1977; Prince 1983; Halle and Vergnaud 1987) and adopt the implementation of

this framework proposed in Idsardi (1992) and Halle and Idsardi (1995), which can

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 37

be summarized as follows. Stress is not a phonetic feature. Rather, it is a phonetic

means for marking certain groupings of linguistic elements. Furthermore, not all

phonemes in the string are capable of bearing stress. This fact is implemented by

having the elements capable of bearing stress project an abstract mark on a separate

plane, the metrical plane. The sequence of abstract marks projected by stressable elements constitutes the line 0 of the metrical plane. These elements are grouped into

what are called feet. This grouping is done by inserting parentheses on the metrical

plane. Idsardi’s (1992) innovation is that only one parenthesis is necessary to group

grid marks: a left parenthesis groups all the marks to its right, and a right parenthesis

groups all the marks to its left. Parentheses are projected either at the edges of the

stress domain (Edge-Marking rules) or at the edges of certain syllables (heavy syllables, a specific syllable in an accented vocabulary item, etc.). Within each foot, a grid

mark (the rightmost or the leftmost one) is designated as the head and is projected

onto the next line in the grid. A new grouping and a relative head are assigned on this

line and thus word stress is determined.

As in Oltra-Massuet and Arregi’s proposal, Idsardi’s notion of Edge Marking

is extended by allowing the projection of metrical parentheses from the syntactic

structure. In particular, as in their analysis of Spanish, the projection of parentheses

is determined by the morphosyntactic structure of the string. The set of rules that

derive stress placement in verbs in Italian is the following:

38 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

(64) Stress algorithm:

a. Project a line 0 mark for each syllable nucleus

(3rd pl. suffix -no and enclitics do not project).

b. On line 0, insert a left parenthesis to the left of the mark projected by the stressable

element preceding a [-present] Tense.

c. On line 0 insert a left parenthesis to the left of mark projected by the stressable element preceding [+part, +plur]AGR.

d. Place a right parenthesis to the left of the right-most element on line 0.

e. Insert a parenthesis every two elements starting from the right-most element.

f. Project the leftmost mark of each line 0 foot onto line 1.

g. Insert a right parenthesis to the right of the rightmost mark on line 1.

h. Project the rightmost mark of each line 1 foot onto line 2.

The basic rule that derives stress placement in finite tenses is (64b). Note that it

makes crucial reference to the syntactic node Tense, not to its phonological realization; that is, it ensures that stress precedes Tense, no matter what the realization of

Tense is.

As an example, here I give the forms of the imperfect, both the indicative and the

subjunctive. All of these forms have the stress pattern in (65), where stress falls on the

vowel realizing the verbal theme position.

(65) Stress in the imperfective

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

ImpInd . . . . . . á v o

ImpSbj . . . . . . á ss i

As shown in (66), the application of stress algorithm (64) gives the right result. First,

(64a) projects stressable elements onto the grid (line 0). Second, (64b) places a left

parenthesis to the left of the mark projected by the stressable element preceding

Tense. In this case the element is the Thematic Vowel. Since, by (64f), feet on line 0

are left-headed, the result is that stress falls on the Thematic Vowel preceding Tense.

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 39

(66) a. 1Sg imperfective indicative (verb cantare ‘sing’)

Line 2

x

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x)

x

String

c a n t - a - v - _21)- o

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

b. 1Sg imperfective subjunctive

Line 2

x

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x)

x

String

c a n t -a -ss -i - Ø

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

Rule (64c) accounts for the stress patterns found in the case of the 1st and 2nd plural.22)

(67) 1Pl imperfective indicative

Line 2

x

Line 1

x

x)

Line 0

x (x

(x)

x

String

c a n t -a -v -a -m o

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T TV ] AGR ]

(68) 2Pl present indicative (verb telefonare ‘phone’)

Line 2

x

Line 1

x

x)

Line 0

x(x x (x)

x

String

t e l e f o n -a

-t e

Syntax

[[ root TV] T +AGR ]

The stress pattern found in the other forms of the present indicative can now be

derived. The rule inserting a left parenthesis on the Thematic Vowel before Tense

21) The TV is deleted before the vowel initial suffix by (33).

22) An exception to (64) is the imperfect subjunctive where the TV preceding the AGR of 1st and 2nd

pl. is not stressed; instead stress is assigned to the TV preceding Tense.

40 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

does not apply. Application of (64d) and (64e) constructs a left-headed foot starting

from the right edge as in (69). Observe that the suffix /-no/ of the 3rd pl. does not

project. The stress pattern constructed in (70) is also found here.

(69) 1Sg present indicative

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x x )

x

String

t elefono

Syntax

[[ root

TV] T+AGR ]

(70) 3Pl present indicative

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x(x x) x

String

t elefon a

no

Syntax

[[ root

TV] T+AGR ]

The last vowel of the root of the verb adorare (/ador/) ‘worship’ is idiosyncratically

marked as projecting a left parenthesis. This vowel will get word stress as shown in

(71). The pattern shown in (71) does not change in the 3rdpl. in (72) because /-no/

does not project on line 0 as discussed above:

(71) 1Sg present indicative

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x)

x

String

a dor -_

-o

Syntax

[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

(i)

1Pl. imperfective indicative

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x

(x

x)

x

String

c a n t - a ss i

mo

Syntax

[[[ root TV ] T TV ] AGR ]

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 41

(72) 3Pl present indicative

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x) x

String

a dor- a _

-no

Syntax

[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

Notice that the left parenthesis inserted before the AGR suffix of 2nd(and 1st) pl. will

trigger rightwards stress shift both in the case of predicate (see (68)) and of adorate

(73):

(73) 2Pl present indicative

Line 2

x

Line 1

x x)

Line 0

x ( x ) (x)

x

String

a d o r -a -te

Syntax

[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

In the regular Passato Remoto, rule (64) will insert a left parenthesis on the Thematic

Vowel preceding Tense–fused with AGR by (45). This will generate the stress pattern shown in (74). Remember that the 3rd pl. /-no/ does not project on line 0 so we

get the same pattern as in (75):

(74) 1Sg Passato Remoto

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x) x

String

cant-a- i

Syntax

[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

(75) 3Pl Passato Remoto

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x ( x) x

String

c a n t -a- r o -no

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T+AGR ]+fissioned [+plur] (see Sect. 3)

42 | 언어와 정보 사회 제18호

This also holds for the 3rd sg. of the II and III conjugations that have a zero-suffix in

this case. The same analysis as discussed above can be given for the 3rd pl: partírono

‘veave’, battérono ‘leave’):

(76) 3Sg Passato Remoto (verb partire ‘leave’)

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x) x

String

p a r t -i -Ø

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

(77) 3Pl Passato Remoto (verb battere ‘beat’)

Line 1

x)

Line 0

x (x)

x

String

ba t t - e

-Ø

Syntax [[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

To account for the 3rd person of the past form where stress falls on the final suffix

instead of the verbal thematic as expected by (64), I assume that, as in Oltra-Massuet

and Arregi’s analysis of similar cases in Spanish, the vocabulary item for this morpheme is exceptionally specified to project a line 0 left parenthesis to its left, as shown

in (78) (where the thematic vowel /-a-/ is deleted before /-ó/ by (33)):23)

(78) 3Sg Passato Remoto

Line 2

x

Line 1

x

x)

Line 0

x (x) (x

String

cant- _

-o

Syntax

[[[ root TV] T+AGR ]

The stress pattern of the athematic forms of the Passato Remoto is now easy to

23) I assume that also the endings of the future (ameró, amerà, etc. ‘love’) and of the conditional

(ameréi, etc.) are exceptionally specified to project a line 0 left parenthesis to their left (see OltraMassuet and Arregi (2005) for an alternative analysis of these tenses in Spanish).

Allomorphy in the Italian Passato Remoto: A Distributed Morphology Analysis | 43

account for. Since no verbal Thematic Vowel is present, the left parenthesis assigned

by Tense will fall on the last vowel of the root. This accounts for why the athematic

roots have root stress, i.e. using the traditional term, for why they are rhizotonic.

(79) 3Sg Passato Remoto (verb mettere ‘put’)

Line 1

x

Line 0

(x)

x

String

mi s _

i

Syntax

[[[ root ]T TV ] AGR ]

(80) 3Pl Passato Remoto

Line 1

x

Line 0

(x

x) x

String

m i s e ro

Syntax

[[[ root ] T TV ] AGR ]

6. An Account of the Alternations in the Passato Remoto

Irregular Forms

We can now provide an account of why the 1st and 2nd pl. and 2nd sg. in (47) display regular morphology. As a reminder, I list here the different forms of the Passato

Remoto of the verbs perdere ‘lose’, scrivere ‘write’ and venire ‘come’:

(81) Singular

1

persi

scrissi

venni

2

perdesti

scrivesti

venisti

3

perse

scrisse

venne

Plural

1

perdemmo

scrivemmo

venimmo

2