Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349 – 365

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijresmar

A paradox of price–quality and market efficiency: a comparative

study of the US and China markets

Kevin Zheng Zhou a,*, Chenting Su b, Yeqing Bao c

a

School of Business, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

b

University of Victoria, Canada

c

University of Alabama, Huntsville, AL, USA

Received 28 August 2001; received in revised form 14 January 2002; accepted 4 April 2002

Abstract

The price – quality schema rests on an assumption that price is credible information about product quality. However, the

credibility of price information varies across different markets. In an inefficient market, consumers would believe in the price –

quality relationship to a lesser extent because price information is less credible. Paradoxically, in such a market, sometimes

consumers have to rely more on price to infer quality because other product information is less available. With a cross-national

perspective, this study investigated the influences of market efficiency and consumer risk aversion on the price – quality schema

between the China and the US markets. We found that due to the inefficient market environment, Chinese consumers possess a

weaker price – quality schema than American consumers. Chinese consumers are more risk averse than their American

counterparts. However, in China, risk-averse consumers are more likely to use price to infer product quality. Implications for

global marketing are discussed, and directions for future research are suggested.

D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: China; Price – quality schema; Market efficiency; Risk aversion; Measurement invariance

1. Introduction

The importance of the price – quality relationship

has kindled an enduring research interest (Dodds,

Monroe, & Grewal, 1991; Lichtenstein & Burton,

1989; Lichtenstein, Ridgway, & Netemeyer, 1993;

Rao & Monroe, 1989; Teas & Agarwal, 2000; Zeithaml, 1988). It is believed that consumers may

assume a positive relationship between price and

product quality and rely on this ‘‘price reliance

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +852-2859-1011;

fax: +852-2858-5614.

E-mail address: kevinzhou@business.hku.hk (K.Z. Zhou).

schema’’ (Peterson & Wilson, 1985) or ‘‘price – quality schema’’ (Lichtenstein et al., 1993) as a shortcut to

make purchase decisions. This belief rests on an

assumption that price is credible information about

product quality in a market. However, few studies in

the price – quality research have scrutinized this

assumption in different national market conditions,

especially in an inefficient market. A question of

interest is that given the different marketing conditions across countries, is the price –quality schema

invariant or robust across markets?

This issue has important managerial implications

for international business operations because marketing strategies should be adapted based on local market

0167-8116/02/$ - see front matter D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 1 6 7 - 8 11 6 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 0 9 6 - 4

350

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

conditions, cultural factors, and consumer behaviors

(Dawar & Parker, 1994; McGowan & Sternquist,

1998). Research has indicated that the price –quality

product strategies can significantly improve firm performance if they match the home-country environments. For example, Brouthers, Werner, and Matulich

(2000) find that a superior-value product strategy

(high quality/low price) performs better in Japan, a

premium product strategy (high quality/high price)

works better in the European Union, and an economy

product strategy (low quality/low price) is more

appropriate in the US market.

As the economy globalizes, marketing in big

emerging markets is vital to Western multinational

companies. However, most former studies have

mainly focused on price –quality issues in developed

markets (e.g., Brouthers et al., 2000; Dawar & Parker,

1994; Lichtenstein & Burton, 1989; McGowan &

Sternquist, 1998). The purpose of this study, therefore,

is to extend our understanding of the price –quality

schema in an inefficient market. In particular, we

examine to what extent consumers in an inefficient

market believe in the price – quality relationship and

how environmental factors (e.g., market efficiency)

and psychological factors (e.g., risk aversion) impact

their beliefs in a price – quality relationship.

We argue that in an inefficient market such as

markets in less-developed countries, consumers would

believe in the price –quality relationship to a lesser

extent because price information is less credible.

Paradoxically, sometimes consumers in such a market

have to rely more on price to infer quality because

other product information is less available or less

reliable. To investigate this paradox, we compare

market efficiency and consumer price – quality schema

between the US and China (PRC), as these two

countries represent two typical different economies

(a developed economy vs. a less-developed or transitional economy) (Luo & Peng, 1999). To further

uncover the effects of market efficiency on consumers’ price – quality schema, we also investigate the

relationships between price –quality schema and risk

aversion, one important psychological factor predicting consumer information search behavior, in these

two markets.

Methodologically, cross-cultural studies have long

been criticized as lacking cross-national measurement

validity (e.g., Durvasula, Andrews, Lysonski, & Nete-

meyer, 1993; Mullen, 1995; Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998). To make any meaningful comparisons

across cultures, the applicability of models developed

in one nation must be assessed in other countries

(Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998). For this purpose,

the cross-national applicability of construct measures

in this study is assessed through multi-model comparison procedures proposed by Durvasula et al. (1993)

and Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998).

2. Price– quality schema

Price – quality schema is defined as ‘‘the generalized belief across product categories that the level of

the price cue is related positively to the quality level

of the product’’ (Lichtenstein et al., 1993, p. 236). It

reflects a consumer’s propensity to use price to make

a judgment of a product’s overall excellence or

superiority (i.e., perceived quality) (Zeithaml, 1988).

As such, the price – quality schema focuses on consumer’s belief of the relationship between price and

perceived quality but not the objective quality (cf.

Lichtenstein & Burton, 1989, p. 429).

The price – quality schema plays an important role

in consumer decision making. It affects the judgments

of perceived quality, influences perceived value and

purchase intentions, and determines information

search and other aspects of consumer decision-making

processes (John, Scott, & Bettman, 1986; Lichtenstein

et al., 1993; Peterson & Wilson, 1985; Zeithaml,

1988). As Tellis and Gaeth (1990) note, if a consumer

is used to inferring the product quality from the price,

he/she actually prefers paying higher prices and

behaves as ‘‘price seeking’’.

Studies have shown that consumers tend to perceive price as positively related to product quality

and some consumers have a higher propensity than

others to use price as a general indicator of quality,

regardless of the product type (e.g., Lichtenstein &

Burton, 1989; Peterson & Wilson, 1985; Rao &

Monroe, 1989). In particular, Peterson and Wilson

(1985) found that consumers could be classified into

groups—‘‘schematics’’ and ‘‘aschematics’’—based

on their belief of the price – quality relationship.

Schematics generally perceive a stronger relationship

between price and quality than aschematics. Lichtenstein and Burton (1989) also confirmed the existence

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

of a price –quality schema and further categorized

consumers into four segments on the basis of their

price – quality perceptions.

Researchers have suggested that the price – quality

schema forms through consumer learning and generalizing process (Peterson & Wilson, 1985). Consumers

develop knowledge about the price –quality relationships for different product categories when abstracting

information over various consumption experiences.

However, few studies have investigated the factors

that underlie the formation of price –quality schema or

explain ‘‘why do price – quality schemas differ?’’

(Lichtenstein & Burton, 1989), especially from a

cross-national perspective.

Recently, there has been some cross-national research on the price – quality schema and price-related

issues. For example, Dawar and Parker (1994) found

that there are few differences in the use of price to

signify quality for a highly homogeneous segment of

consumers across Western industrialized countries and

Japan. McGowan and Sternquist (1998) compared

Japanese and US young consumers in terms of their

price – quality schema, prestige sensitivity, and value

consciousness. Results suggested that price-inference

behaviors may be market-universal for a similar segment of Japanese and US consumers. These studies,

however, have exclusively focused on comparing

consumer price – quality perceptions across developed

markets, where market conditions are comparatively

homogeneous and efficient.

As the first attempt to study the price – quality

schema in a less-developed market, Veeck and Burns

(1995) successfully grouped urban Chinese consumers into schematics and aschematics based on their

price – quality perceptions. This finding contrasts with

that of the US studies, which have documented the

existence of three or four distinct schematic groups

(e.g., Lichtenstein & Burton, 1989). However, Veeck

and Burns focused mainly on classifying Chinese

consumers into different groups. Little effort has been

paid to the market conditions which affect the credibility of market information and thus the schematic

differences between Chinese and American consumers. As a consequence, a set of research issues remain

unanswered, that is: why do Chinese consumers differ

from American consumers in their beliefs in price –

quality relationship? How is the price –quality schema

affected in an inefficient market like China? As Veeck

351

and Burns note, these issues provide challenges for

future research on the price –quality relationship. In

the next section, we try to explore these questions by

examining how market efficiency affects the formation of a price – quality schema and how consumer risk

aversion influences a price –quality schema in different market environments, particularly, China and the

US.

3. Research hypotheses

3.1. Market efficiency and price – quality schema

A market is efficient if all relevant and ascertainable information is widely available to participants

(Gabriel & Marsden, 1990). Ideally, in an efficient

market, all the information changes are reflected in

price changes (Rosen, 1974). Market efficiency may

result from perfect competition and intensive communication and some product market may be more

efficient than others. As Chernev and Carpenter

(2001, p. 350) note,

In the case of personal computers, differences

between products are often perceived as minimal,

which forces manufacturers to offer comparable

packages. For other products, such as wine, for

which value is more subjective and consumers are

less knowledgeable, much less pressure exists to

offer the products at value parity with competitors.

In this example, the personal computer market is

more efficient than the wine market, as the competition and communication are more intense and ascertainable information is widely available and understandable to consumers.

In the marketing literature, studies on market

efficiency have mainly focused on the relationship

between market efficiency and objective product

quality (e.g., Hjorth-Anderson, 1984; Ratchford,

Agrawal, Grimm, & Srinivasan, 1996). However,

how consumers’ perceptions of market efficiency

affect their beliefs, values, and behaviors remains

unexplored (Chernev & Carpenter, 2001). Here, we

extend the current research by examining how one’s

perception of market efficiency impacts the formation

of his/her price – quality schema.

352

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

As discussed earlier, a price – quality schema forms

through consumer learning and generalizing processes

about the price – quality relationship (Peterson & Wilson, 1985). In a highly efficient market, brands offer

value parity, so that any additional value offered by a

product is equal to its marginal price (Rosen, 1974).

Because all the information is available to consumers,

they may learn through experience that, in this market,

equal-priced products offer comparable values and a

higher price indicates a higher quality. Over time,

consumers form a general belief of a positive price –

quality relationship, i.e., ‘‘you get what you pay for’’.

In a less-efficient market, low-quality, high-priced

products are able to survive, because the competition

is not intense and/or product quality information is not

available or difficult to assess (Lichtenstein & Burton,

1989). Consumers may find that some necessary

information is not available, the searching cost is

too high, or the product information is ambiguous to

evaluate (Chernev & Carpenter, 2001). From the

experience, consumers could gradually learn the inefficiency of the market and that price is not a good

indicator of product quality. This suggests that consumer price – quality schema will be affected by their

perceptions of market efficiency. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1 . The more consumers perceive the market as

efficient, the stronger their price –quality schemas.

As an emerging market, the China market is not as

efficient as the US market. In the latter, the intense

competition makes abundant and comparable goods

available to every consumer. American companies

also tend to use various sale and promotion campaigns

in order to attract consumers. In contrast, market

competition in China is relatively low, Chinese consumers are more concerned with the availability and/

or the quality instead of the price of a satisfactory

product (Batra, 1997). Further, in the US, detailed

product information is available from a number of

sources such as Consumer Reports and the Internet.

While in China, where the communication level is

low, detailed product information is difficult to

acquire and reliable information source may not be

available to most consumers (Ho, 2001).

As in the transition from a planned central economy to a market economy, market regulation and

legislation by the government and business self-regu-

lation in China are much less refined compared with

those in the US (Batra, 1997). In China, deceptive

advertising (exaggerated and fraudulent advertising),

trademark violation (counterfeit goods with poor

quality but always under the names of popular

brands), and unethical business practices (e.g., selling

poor-quality products at very high prices) are malpractices that have aroused particular concerns to the

public (Ho, 2001; Ho & Sin, 1988).

The above discussion suggests that the US market

is more efficient than the China market. Therefore,

price is a relatively credible indicator of product

quality in the US. Over time, American consumers

will come to understand the efficient nature of the

market. Accordingly, they may rely more on price cue

to indicate product quality as a heuristic way to reduce

information-searching costs and facilitate decision

making. In contrast, the less-intensive competition,

low level of communication, and weak regulations

lead to a less fair pricing system in China. Some

products are overpriced (such as counterfeit products),

while others are underpriced (e.g., plagiarism products). Because ascertainable information is unavailable, Chinese consumers will perceive the market as

less efficient and thus, tend to doubt the credibility of

price in indicating product quality. Therefore, we

predict the following.

H2 . The China market is perceived less efficient than

the US market.

H3 . Chinese consumers possess a weaker price –

quality schema than American consumers.

H1 – H3 investigate the impact of market efficiency

on the formation of price – quality schema. In the

following hypothesis development, we further assess

how market efficiency moderates the relationship

between risk aversion and price – quality schema.

3.2. Risk aversion and price – quality schema

In cross-cultural settings, risk aversion refers to

one’s general tendency to avoid uncertainty (Hofstede,

1980). It reflects ‘‘the extent to which people feel

threatened by ambiguous situations and have created

beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these’’ (Hofstede & Bond, 1984, p. 419). This concept captures

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

the cultural pattern of seeking stability, predictability,

and low stress rather than volatility and new experiences. Risk-averse people are inclined to feel threatened by uncertain situations (Hofstede, 1991).

Past research suggests that Americans value risk

seeking, while Chinese tend to be risk averse (Hofstede, 1980). China is a typical collectivistic society in

which people tend to act as a group. To sustain withingroup harmony, people are expected to abide by

certain behavioral codes. Risk-taking behavior is

regarded as a challenge to the group’s interest and

existence and is thereby often discouraged (Triandis,

1995). In contrast, the US is a typical individualistic

society in which people tend to view themselves as a

unique set of internal attributes such as motivations,

traits, and values (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Individuals are willing to and encouraged to make their

own decisions and are responsible for their decisions

and behaviors. Exploring uncertainty is regarded as

one’s merit in life and thus is fostered (Triandis,

1995). These arguments suggest the Chinese to be

more risk averse than the Americans. Since this

prediction has been tested in former studies, it is

treated here as a replication hypothesis.

H4 . Chinese consumers are more risk averse than

American consumers.

Risk aversion affects consumers’ decision making

in various ways (e.g., Rao & Bergen, 1992; Shimp &

Bearden, 1982). Risk-averse consumers feel threatened by ambiguous and uncertain purchasing situations. They tend to search for more information

regarding quality from information sources such as

Consumer Reports before making a decision (Shimp

& Bearden, 1982). If such information is easy to get,

risk-averse consumers can rely on the information to

decrease their perceived risk. If such information is

not available or not credible, risk-averse consumers

have to rely more on extrinsic cues such as price,

brand, or store image to infer product quality (Zeithaml, 1988, p. 9).

In the US market, the intense competition makes

comparable goods available to every consumer. Product information is abundant due to various sales and

promotional campaigns and efficient mass communication. Objective product quality information is also

easily assessable from external sources such as Consumer Reports. In addition, due to the extensive

353

regulations, American companies are less likely to

provide deceptive information (such as deceptive

advertising) than Chinese companies. As a result,

for American consumers, product information is not

only easy to get but credible as well. To reduce their

risk perceptions, risk-averse consumers can conduct a

thorough research and analysis of product information

provided in a marketing communication campaign or

other third parties (Grewal, Gotlieb, & Marmorstein,

1994). With intrinsic cues or other objective information, consumers are less likely to use price to infer

product quality (Dodds et al., 1991; Zeithaml, 1988).

Hence, risk-averse consumers in the US will rely less

on price to evaluate a product.

H5a . In the US market, the more risk averse the

consumers, the weaker their price – quality schema.

As a transitional economy, the China market is less

efficient and characterized by lack of coherent business regulations and legislation, less-intense competition, and low levels of mass communication (Batra,

1997; Luo & Peng, 1999; Nee, 1992). Deceptive

advertising, counterfeit products, and unethical business practices are prevalent in the market (Fan &

Xiao, 1998). Chinese consumers have to be very

cautious about the information in the ad and have to

distinguish counterfeit products by themselves (Ho,

2001). However, due to the low level of mass communication, it is difficult for Chinese consumers to

obtain sufficient product information to judge the

product quality and other objective information sources such as Consumer Reports are not available to

most consumers.

When lacking information, especially when credible information is unavailable, risk-averse consumers

have to infer product quality from available cues.

Extrinsic cues such as price, brand, and store information thus will be used more heavily (Zeithaml,

1988). However, the retailing system is fragmented

and the distribution channel is long in China. Western countries usually have 50 –80% of sales occurring through large chains, but such large or national

retailing chains are nearly absent in China (Batra,

1997). As Batra (p. 101) notes, ‘‘the retail sector in

China now consists of about 9.2 million very small

(one- and two-person) retail shops . . .’’ Most stores

cannot guarantee the quality of the products it sells.

As a result, consumers can hardly depend on store

354

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

information to evaluate a product. Further, trademark

violation is prevalent in China and counterfeit products can be seen everywhere (Fan & Xiao, 1998; Ho,

2001). These products, on one hand, cause reputation

damages for name, and high-quality brands (Batra,

1997), on the other hand, make consumers rely less

on brand to assess quality. Because extrinsic cues

such as brand and store image are less dependable,

price, as a relatively unambiguous cue, will have a

greater effect on product quality judgment (Dodds et

al., 1991).

In sum, because objective quality information is

not available and intrinsic product information is less

credible in China, risk-averse consumers have to rely

more on extrinsic cues to evaluate a product to reduce perceived risks. Further, they are forced to use

price as an indicator of quality, because brand and

store information is even less dependable. Hence, we

predict,

H5b . In the China market, the more risk averse the

consumers, the stronger their price – quality schema.

4. Methods

Measurement reliability and validity across nations

have long been a serious concern for cross-national

studies. In particular, the equivalence of samples,

constructs, and measurement across countries must

be empirically assessed to ensure valid comparisons

(Dawar & Parker, 1994; Mullen, 1995; Steenkamp &

Baumgartner, 1998).

4.1. Survey design

A survey study was conducted to collect data in

both the United States and China. Singh (1995)

suggested that it is necessary to assess the scale

validity before cross-national data collection. Therefore, a pretest was conducted among 40 college

students in the US to test the measures for this study.

Some items were deleted according to the pretest, and

some were modified to enhance clarity.

To measure theoretical constructs cross-nationally,

translation equivalence must be considered (Mullen,

1995). Following Mullen’s suggestion, an original

survey was designed in English, and was then trans-

lated to Chinese by a bilingual speaker. The Chinese

version of questionnaire was then back-translated to

English by another bilingual person. Discrepancies in

the translation were carefully inspected and corrected

to ensure equivalence in the questionnaire. The English and Chinese versions of the measurement items

are presented in Appendix A.

4.2. Sampling

Young consumers are especially studied because:

(1) young consumers are recognized as a specialized

global market segment for a variety of goods and

services (Moschis & Moore, 1979), and (2) in China,

compared with the older generations, the young have

more appetites for, and consuming experience with,

Western products, and are more likely to be the

potential consumers for Western companies (Anderson & He, 1998).

A matched sample of respondents is required in a

cross-national study (Dawar & Parker, 1994). For this

reason, college students were recruited as subjects in

both China and the US. The samples are not nationally representative, but constitute comparable populations (Durvasula et al., 1993, p. 628) and are an

important component of the target population. Altogether, 222 completed questionnaires were obtained,

in which 106 from a large state university in the US

and 116 from a large state university in China. The

demographic characteristics of the sample were similar in these two data sets. For example, all the

Chinese subjects were undergraduate students,

49.1% were junior, and aged between 18 and 25 years

old with a mean of 20.4. All the American subjects

were also undergraduate students, 72.9% were junior,

and aged from 19 to 27 with a mean of 21.1.

Dawar and Parker (1994) also note that economic

factor is another important matching criteria for a

matched sample. Thus, financial concern, one key

economic variable, was included to check this concern. Given that this study is conducted in a crossnational context, a measure indicating subjective

financial concern would be more appropriate than a

measure of objective financial status. The measure of

financial concern (see Appendix A) is adapted from

Mandrik, Fern, and Bao (1999) and results indicate no

significant difference (MEANus = 4.506, MEANchina = 4.417, Dv2(1) = 2.684, p>0.10, multi-model

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

comparison used, see Section 5 for more methodological details). Thus, we concluded that the

samples used in this study are matched and comparable.

4.3. Measures

Price – quality schema was measured with four

seven-point Likert scale items (see Appendix A)

adapted from Lichtenstein et al. (1993). The measure of perceptions of market efficiency was specifically designed for this study. The initial measure

included a number of items pertaining to market

competition and information availability (cf. Chernev & Carpenter, 2001), such as ‘‘there are a lot of

alternative brands available even for a specific

brand,’’ and ‘‘I can easily collect plenty of information about the price and quality of a product.’’

Based on the pretest, three items were retained in

the final questionnaire.

As discussed earlier, in cross-national settings, risk

aversion refers to one’s general tendency to avoid

uncertainty (Hofstede, 1980). Although Hofstede et

al. developed a set of measurements for uncertainty

avoidance, their measures are more related to people’s

behavior in an organizational context, thus are not

directly applicable to the consumer decision-making

context. In order to reflect consumers’ general uncertainty avoidance pertaining to purchase, the measurement of risk aversion developed by Raju (1980) was

adapted. Based on pretest, three items were used in the

final survey.

4.4. Measurement invariance assessment

Measurement invariance refers to whether or not

the measurement operations yield measures of the

same attribute under different cultures or countries

(Mullen, 1995). If a measure is not cross-nationally

invariant, conclusions based on that scale are ‘‘at best

ambiguous and at worst erroneous’’ (Steenkamp &

Baumgartner, 1998, p. 78). For example, if we compare price –quality schemas between American and

Chinese consumers without assessing the measurement invariance, then we will not be able to tell

whether the difference (if any) comes from consumers’ price perceptions or just from their semantic

interpretations of the questionnaire.

355

To make valid cross-national comparisons, it is

necessary to establish configural invariance, metric

invariance, and scalar invariance for measurement

instruments (Mullen, 1995). First, the measurement

should be configurally invariant (i.e., the same

pattern of factor loadings across different cultural

groups). Second, the measurement should be metrically equivalent for at least two items (i.e., equal

loadings for the two items across cultural groups).

Third, at least two items should be scalar invariant

(i.e., equal intercepts for those two items across

cultural groups) (cf., Steenkamp & Baumgartner,

1998). These three steps are accumulative, and the

former step is the necessary condition for the latter

steps.

Based on the multigroup comparison procedures

proposed by Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998),

the measurement instrument for each construct is

examined, and cross-cultural invariance is assessed

using AMOS 4.0 with maximum likelihood as the

estimation method (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999).

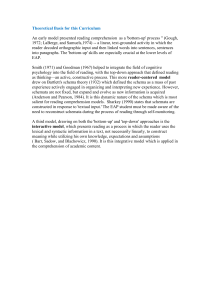

For illustration purposes, the measurement invariance test for price –quality schema is illustrated in

Fig. 1.

4.4.1. Price – quality schema

The first step was to test the equality of covariances and means of the four indicators of this measure

across two groups: China and the US (see Fig. 1a).

The test results were: v2(14) = 58.087, p < 0.001; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.983, Tucker – Lewis index

(TLI) = 0.975; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.120, Akaike information criterion

(AIC) = 86.087. The significance of chi-square and the

relatively large RMSEA and AIC indicated the lack of

invariance of covariance matrices and mean vectors

across the two samples.

Thus, we turned to the test of the configural

invariance, which means that indicators should load

on the factor in a similar pattern across countries

(see Fig. 1b). This model was the baseline model

against which further models could be compared.

The results (v2(4) = 9.481, p = 0.050; CFI = 0.971,

TLI = 0.912; RMSEA = 0.079, AIC = 41.481) indicated a good fit of the model. All factor loadings

were highly significant in both countries ( p <

0.001), and standardized factor loadings ranged

between 0.45 and 0.82. Therefore, the measure of

356

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

Fig. 1. An example of measurement invariance test.

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

price – quality schema was configurally invariant

across the US and China samples.

Next, we tested the metric invariance which means

that the matrix of factor loadings was invariant across

countries (see Fig. 1c). The results (v2(7) = 11.195,

p = 0.130; CFI = 0.978, TLI = 0.962; RMSEA = 0.052,

AIC = 37.195) showed that the increase in chi-square

was not significant (Dv2(3) = 1.714, p = 0.634) and

TLI, RMSEA, and AIC actually improved. Thus, the

price – quality schema was also fully metric invariant

across the US and China samples.

Finally, the scalar invariance was tested. The

intercepts of the four indicators were set to be invar-

357

iant across countries (see Fig. 1d). Such a model

resulted in an acceptable fit (v2 (11) = 20.962,

p = 0.034; CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.993; RMSEA = 0.064,

AIC = 54.962). The increase of chi-square over the

full configural invariance model was not significant

(Dv2(7) = 11.482, p = 0.119); CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and

AIC also exhibited a good fit. Thus, full scalar

invariance was supported.

The previous procedure was run for measures of

market efficiency perception, risk aversion, and financial concern. Note that if the full metric or scalar

invariance model was not adequate, then constraints

on certain indicators (as revealed by the Modification

Table 1

Assessment of measurement invariance

Model

v2

df

p-value

CFI

TLI

RMSEA

AIC

Relaxed

constrainta

Price – quality schema

Equality of covariances and means

Configural invariance

Full metric invariance

Final partial metric invariance

Initial full scalar invariance

Final partial scalar invariance

58.087

9.481

11.195

–

20.962

–

14

4

7

–

11

–

0.000

0.050

0.130

–

0.034

–

0.983

0.971

0.978

–

0.996

–

0.975

0.912

0.962

–

0.993

–

0.120

0.079

0.052

–

0.064

–

86.087

41.481

37.195

–

54.962

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Perception of market efficiency

Equality of covariances and means

Configural invariance

Full metric invariance

Final partial metric invariance

Initial full scalar invariance

Final partial scalar invariance

207.260

0

5.250

–

80.978

13.303

9

0

2

–

5

4

0.000

–

0.072

–

0.000

0.008

0.895

1.000

0.986

–

0.944

0.974

0.860

–

0.958

–

0.896

0.942

0.316

–

0.086

–

0.250

0.089

225.260

24.000

25.250

–

106.978

32.303

–

–

–

–

–

ME3

Risk aversion

Equality of covariances and means

Configural invariance

Full metric invariance

Final partial metric Invariance

Initial full scalar invariance

Final partial scalar invariance

72.802

0

2.301

–

66.135

14.121

9

0

2

–

5

4

0.000

–

0.317

–

0.000

0.007

0.962

1.000

0.997

–

0.964

0.994

0.950

–

0.990

–

0.914

0.982

0.180

–

0.026

–

0.236

0.107

90.802

24.000

22.301

–

92.135

42.121

–

–

–

–

–

RISK3

Financial concern

Equality of covariances and means

Configural invariance

Full metric invariance

Final partial metric invariance

Initial full scalar invariance

Final partial scalar invariance

41.025

0

3.535

–

32.540

11.389

9

0

2

–

5

4

0.000

–

0.171

–

0.000

0.023

0.979

1.000

0.980

–

0.982

0.995

0.971

–

0.940

–

0.956

0.985

0.127

–

0.059

–

0.158

0.092

59.025

24.000

23.535

–

58.540

39.389

–

–

–

–

–

FS1

a

See Appendix A for details on the scale items.

358

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

nationally invariant and their means could be compared meaningfully (Steenkamp & Baumgartner,

1998).

Index [MI]) were relaxed to get an acceptable partial

invariance model (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998).

The details of construct invariance assessment are

reported in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that the measure of price –quality

schema is configurally invariant, fully metric invariant, and fully scalar invariant. Measures of market

efficiency perception, risk aversion, and financial

concern are also configurally invariant and fully

metric invariant, but not fully scalar invariant. Nevertheless, all the partial scalar invariance models are

acceptable. Therefore, these measures are cross-

4.5. Measurement model analysis

Measurement reliability and validity is assessed by

estimating a three-factor confirmatory measurement

model at both the national level (i.e., China and the

US) and the multigroup level (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988; Durvasula et al., 1993). In the model, each item

was set to load only on its own factor, and the factors

Table 2

Across-construct measurement validity assessmenta

American sample

Construct

Price – quality schema

PQ1

PQ2

PQ3

PQ4

Perception of market efficiency

ME1

ME2

ME3

Risk aversion

RISK1

RISK2

RISK3

Chinese sample

Factor

loading

Composite

reliability

Construct

0.822

Price – quality schema

PQ1

PQ2

PQ3

PQ4

Perception of market efficiency

ME1

ME2

ME3

Risk aversion

RISK1

RISK2

RISK3

1.000b

0.700

0.925

0.848

0.856

0.646

1.000b

1.215

0.671

0.617

1.000b

0.772

Factor

loading

Composite

reliability

0.600

1.000b

0.698

0.723

0.788

0.754

0.556

1.000b

0.790

0.652

1.050

1.000b

0.899

Goodness-of-fit statistics

American sample:

Chinese sample:

Multigroup level:

v2 = 50.429, df = 32, p = 0.020; GFI = 0.919, CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.074

v2 = 48.010, df = 32, p = 0.034; GFI = 0.924, CFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.920; RMSEA = 0.066

v2 = 98.442, df = 64, p = 0.004; GFI = 0.922, CFI = 0.936, IFI = 0.939; RMSEA = 0.049

U Matrixc

US

1

China

2

3

1

1.000

0.156

1.000

3.414

1.358

4.957

0.876

Price – quality schema

Perception of efficiency

Risk aversion

1.000

0.152

0.023

1.000

0.066

1.000

1.000

0.249d

0.280d

Meanc

S.D.

5.024

1.043

5.079

0.854

4.164

1.109

4.698

0.889

a

All factor loadings statistically significant at p < 0.01.

Fixed parameter.

c

Measures reversed and averaged by the number of scale items.

d

p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

b

2

3

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

were allowed to correlate. The results of measurement

analysis are exhibited in Table 2, which also reports the

means and standard deviations of the three measures.

To make the comparison more intuitive, construct

means are averaged and reverse coded.

All three models provided an acceptable fit to the

data (American sample: v2(32) = 50.429, p = 0.020;

GFI = 0.919, CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.950; RMSEA =

0.074; Chinese sample: v2(32) = 48.010, p = 0.034;

GFI = 0.924, CFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.920; RMSEA =

0.066; multigroup level: v2(64) = 98.442, p = 0.004;

GFI = 0.922, CFI = 0.936, IFI = 0.939; RMSEA =

0.049). Although the v2 tests were significant, the

goodness-of-fit measures were all satisfactory and the

RMSEAs were below the 0.08 rule of thumb (Bollen,

1989). These results indicate the unidimensionality

of the measures (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Further, all factor loadings were statistically significant

359

( p < 0.01) and the composite reliabilities of each

construct all exceeded the usual 0.60 benchmark

(Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Thus, these measures demonstrate adequate convergent validity and reliability.

Moreover, all the cross-construct correlations were

significantly smaller than A1.00A ( p < 0.01), signifying the discriminant validity of these measures (Phillips, 1981). Overall, these results show that the

measures in this study possess adequate reliability

and validity.

5. Results

We tested H2, H3, and H4 with structural equation method, which is advantageous to the traditional

ANOVA/MANOVA approach by incorporating errors

in construct measurement (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989;

Table 3

Results of hypotheses testing

H2, H3, and H4

Mean

Chi-square

US

China

DMean

Dv2

v2 (67) = 196.046

v2 (65) = 187.686

97.604a

89.244a

v2 (65) = 105.227

v2 (65) = 110.348

6.784a

11.905a

5.079

3.414

1.665

v2 (64) = 98.442

v2 (64) = 98.442

5.024

4.164

4.698

4.957

0.326a

0.793a

v2 (64) = 98.442

v2 (64) = 98.442

H1, H5a and H5b

Endogenous latent variables — standardized coefficients (t-value)

Independent

latent variables

Price – quality

schema (US)

H1: Perceptions of

market efficiency (ME)

H5a, H5b:

Risk aversion (RA)

R-square

U correlation between

ME and RA

Goodness-of-fit

measures

a

p < 0.01.

p < 0.10 (one-tailed).

c

p < 0.05 (one-tailed).

b

Price – quality

schema (China)

0.155b (1.385)

0.300c (2.111)

0.033 (

0.327c (2.020)

0.265)

0.024

0.066

v2 = 50.429, df = 32,

p = 0.020; GFI = 0.919,

CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.950;

RMSEA = 0.074

M1)

M2

(constrained)

Overall test

H2: Perceptions of

market efficiency

H3: Price – quality schema

H4: Risk aversion

a

(M2

M1

(unconstrained)

0.166

0.156

v2 = 48.010, df = 32,

p = 0.034; GFI = 0.924,

CFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.920;

RMSEA = 0.066

360

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

Durvasula et al., 1993). As Durvasula et al. (1993)

suggest, two models were first compared to assess

the overall mean differences (price –quality schema,

market efficiency perception, and risk aversion)

across two data sets (similar to MANOVA). One

model freely estimated all means across countries

(M1, unconstrained model), and the other assumed

that construct means were equal across countries

(M2, constrained model). The v2 difference between

M1 (v2(64) = 98.442) and M2 (v2(67) = 196.046) was

highly significant (Dv2(3) = 97.604, p < 0.001), indicating that the construct means are significantly

different across countries. Then, individual construct

mean tests were performed with similar techniques

(similar to ANOVA). The results are reported in

Table 3.

H2 deals with consumer perceptions of market

efficiency. As predicted, the China market (l =

3.414) is perceived less efficient than the US market

(l = 5.079). A comparison between M1 and M2

(Dv2(1) = 89.244, p < 0.001) indicates that the difference is highly significant. These findings support

H2.

H3 argues that Chinese consumers possess a

weaker price – quality schema than American consumers. The results in Table 3 show that the mean value of

Chinese sample (4.698) is significantly less than that

of American sample (5.024, Dv2(1) = 6.784, p < 0.01),

lending support to H3.

H4 deals with the extent of risk aversion between

American and Chinese consumers. Table 3 shows that

the change of chi-square is highly significant

(Dv2(1) = 11.905, p < 0.001), indicating that Chinese

consumers (l = 4.957) are more risk averse than

American consumers (l = 4.164). Thus, H4 is supported.

H1, H5a, and H5b focus on the relationships

between market efficiency, risk aversion, and price –

quality schema. As suggested by Steenkamp and

Baumgartner (1998, p. 82), the structural equation

model was applied to test this relationship across

countries so that the potential lack of error variance – invariance does not create a problem. In the

model, price – quality schema is the dependent variable and perceptions of market efficiency and risk

aversion are the two independent variables. Results

(see Table 3) show that the model fit the data

satisfactorily (American sample: v2(32) = 50.429,

p = 0.020; GFI = 0.919, CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.950;

RMSEA = 0.074; Chinese sample: v2(32) = 48.010,

p = 0.034; GFI = 0.924, CFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.920;

RMSEA = 0.066).

H1 predicts that consumer perception of market

efficiency is positively related to their price – quality

schema. Table 3 shows that for American consumers,

price – quality schema is positively related to market

efficiency perception (b = 0.155, p < 0.10, marginally

significant); for Chinese consumers, their perceptions

of market efficiency positively affect their price –

quality schema (b = 0.300, p < 0.05). These results

lend support to H1.

H5a and H5b states that the relationship

between risk aversion and price – quality schema is

negative in the US (H5a) but positive in China

(H5b). Contrary to H5a, the results show that risk

aversion is not significantly related to price – quality

for American consumers (b = 0.033, p>0.10).

Thus, H5a is not supported. For the Chinese

sample, risk aversion is positively linked to

price – quality schema (b = 0.327, p < 0.05), supporting H5b.1

5.1. Post-analysis

Some post-analyses were run to further examine

the relationships of price – quality schema, market

efficiency, and risk aversion. More specifically, which

factor is more important in influencing the formation

of price – quality schema, risk aversion or market

1

When developing H5b, we did a qualitative analysis to show

why price has a greater effect on product quality judgment than

either brand or store image. We also indirectly tested this reasoning

with proxy measures of brand and store-image effects. In the survey,

there is one question pertaining to consumer’s general perception of

store (Store: ‘‘It is difficult for me to find a satisfactory store to go

shopping’’, reversed scale) and one item of consumer’s perception

of name brand (Brand: ‘‘The well-known national brands are best

for me’’). Both are seven-point Likert scales. Though these two

items do not focus on the store/brand – quality relationship, we

could use them as proxy indicators. A comparison between PQ,

Store, and Brand shows that in China, PQ (m = 4.70) is greater than

Brand (m = 3.84, p < 0.001), Brand greater than Store (m = 3.24,

p < 0.01), and PQ greater than Store ( p < 0.001). These results

indirectly suggest that in China, the price information is perceived

as more credible than either brand or store information, and store

information is the least dependable.

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

efficiency? Further, do market efficiency and risk

aversion have similar effects on price – quality schema

across these two countries?

To answer these two questions, a series of

model comparison tests were run between unconstrained models (where b’s are freely estimated)

and constrained models (where b’s are constrained

to be equal). For question 1, the results show that

in the US, the impact of market efficiency upon

price – quality schema is slightly stronger than that

of risk aversion (Dv2(1) = 2.740, p < 0.10). However, in China, there is no significant difference

between the impacts of market efficiency and risk

aversion (Dv2(1) = 0.182, p>0.10). For question 2,

the results indicate that risk aversion has a stronger

impact on price –quality schema in China than in

the US (Dv2(1) = 3.156, p < 0.10), while market

efficiency has a similar effect on price – quality

schema in these two countries (Dv2(1) = 0.002,

p>0.10).

6. Discussion and conclusions

The major objective of this research is to understand consumer’s price –quality schema in an inefficient market. Our findings generally support the

hypothesized relationships. Basically, we found that

market efficiency positively affects the formation of

price – quality schemas. In an inefficient market, consumers believe the positive relationship between price

and quality to a less extent, but paradoxically, riskaverse consumers have to rely more on price to infer

product quality.

We compared market efficiency and price – quality schema in the China and US market. Our

findings show that market efficiency has a positive

impact on consumer beliefs of price – quality relationship. As Peterson and Wilson (1985) suggest,

price – quality schema develops through consumer

experience and generalizing process. If, over time,

consumers get to know the efficiency (or inefficiency) of the market through experience, they will

(more or less) use price to indicate product quality.

Our findings also indicate that the China market is

perceived much less efficient than the US market.

At the macro-level, market and management literatures have long recognized the inefficiency of a

361

transitional economy such as China (e.g., Nee, 1992;

Luo & Peng, 1999). Our findings further suggest

that at the individual level, market efficiency will be

reflected into consumer perceptions of market conditions. Since Chinese consumers perceive the market as less efficient than American consumers, and

market efficiency perceptions affect consumer

price –quality schemas, Chinese consumers possess

a weaker price – quality schema than their American

counterparts. These results echo the recent call of

Chernev and Carpenter (2001) for more research on

how consumer understanding of market efficiency

affects their beliefs and decision makings.

To further uncover the effect of inefficient market conditions on consumer price –quality schema,

the relationship between risk aversion and price –

quality schema was investigated from a crossnational perspective. Previous research has already

indicated that risk-averse consumers tend to search

for more product information in purchase decisions

(e.g., Shimp & Bearden, 1982). When reliable

product information is unavailable, these consumers

are inclined to rely on extrinsic cues such as price

and brand to infer product quality (Dodds et al.,

1991; Zeithaml, 1988). We found that in China,

where the economy is in a transitional process from

a central planned one to a market one, ascertainable

and credible in product information is hardly available; therefore, risk-averse consumers are forced to

rely more on price to infer product quality. These

findings support the proposition of Dodds et al. in

an inefficient market.

The hypothesis that consumer risk aversion is

negatively related to their price – quality schema in

the US market is not supported. In other words, in

the US, more risk-averse and less risk-averse consumers may use price to infer product quality at

similar levels. One possible explanation may be that

in the US market, product information is so abundant

that information search and analysis becomes a

burden to many consumers. That is, information

overload increases the time and cost of information

search. As a result, consumers may rely on their

price – quality schema to conserve the efforts and

shortcut the decision making, even if they are risk

averse.

In sum, our findings disclose an interesting paradox of price – quality schema in an inefficient mar-

362

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

ket. That is, in a transitional economy, Chinese

consumers in general doubt the credibility of price

as an indicator of product quality (H1 – H3). However, still due to the market environment, riskaverse consumers are forced to rely more on price

to infer price quality (H4, H5a, and H5b). An

intuitive explanation of the paradox may be that

Chinese consumers believe ‘‘a high price does not

mean high quality, but a high-quality product must

have a high price.’’

Our findings also provide some implications for

companies seeking opportunities in China. In

China, consumers in general are less confident

about product –quality relationship due to the poor

market environment. However, sometimes, they

(highly risk-averse consumers) have to rely on

price to infer product quality. Thus, enhancing

consumers’ confidence with detailed product information, company information, and a high price

might be a way to go. Other market cues such

as store reputation and brand name should be

provided to assure the product quality and prevent

the impairment of counterfeit products. Further,

because market efficiency impacts consumers’ use

of price to evaluate a product, and the market

conditions vary widely across different areas within

China (Ho, 2001), companies may also need to

adapt their strategies across different areas and

markets, even within China.

6.1. Research implications

This research advances our understanding of

price – quality schema in an inefficient market

and provides some preliminary explanations of

why consumers differ in price – quality schema. It

appears that both market environmental factors

(e.g., market efficiency) and consumer psychological characteristics (e.g., risk aversion) have

impacts on the formation of price – quality schema

in an inefficient market, suggesting the importance

of considering both market environmental and

individual psychological factors in cross-national

studies.

Methodologically, we made efforts to establish

cross-national measurement equivalence before making comparisons. In line with researchers’ recommendation (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989; Durvasula et al., 1993;

Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998), this study assessed

and verified the cross-national invariance of the focal

construct measures; mean comparison and association

analysis were also conducted with structural equation

methods. As such, this research contributes to the

cross-national consumer research. Future researchers

could directly apply the measures of price – quality

schema, market efficiency perception, risk aversion,

and financial concern in studies involving American

and Chinese consumers.

However, we must caution that one should not

overgeneralize the results of this study and we encourage future research to overcome the limitations of this

paper. First, the sample is comprised of students;

therefore, samples from other segments are needed

to generalize the findings to other populations. Second, this study was conducted in two countries, China

and the US. Obviously, research conducted in other

countries is necessary to test the robustness of the

findings. Further, because our study was cross-sectional, we cannot determine the causal links of the

model with certainty. Experimental research is needed

to test whether our theoretically based causal model

will be fully supported. To further understand the

paradox identified, it is worthwhile to cross market

efficiency, risk aversion, and other factors such as

price and brand in a complete factorial design, and

then test why consumers may rely more on price to

indicate quality. Is it because they want to reduce high

levels of risk perceptions? Or maybe it depends on

consumer product knowledge and/or purchase

involvement? Finally, it would be interesting to examine whether consumers’ price – quality schema

changes in a different country where the market

efficiency level differs. This will provide more

insights for us to understand important questions such

as the persistency of the price – quality schema and

whether the price – quality schema is country-specific

or consumer-specific.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to

the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their

invaluable suggestions on previous versions of the

article. We also thank Kent Nakamoto for his

comments and suggestions.

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

363

Appendix A . Measurement appendix

All the items are anchored from ‘‘1’’ (strongly

agree) to ‘‘7’’ (strongly disagree).

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation

modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411 – 423.

Anderson, P. M., & He, X. (1998). Price influence and age segments of Beijing consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing,

15(2), 152 – 169.

Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 user’s guide.

Chicago: SmallWaters.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural

equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

16, 74 – 94.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1989). On the use of structural equation

364

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

models in experimental designs. Journal of Marketing Research,

26, 271 – 284.

Batra, R. (1997). Marketing issues and challenges in transitional

economics. Journal of International Marketing, 5(4), 95 – 114.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables.

New York: Wiley.

Brouthers, L. E., Werner, S., & Matulich, E. (2000). The influence

of triad nations’ environments on price – quality product strategies and MNC performance. Journal of International Business

Studies, 31(1), 39 – 62.

Chernev, A., & Carpenter, G. S. (2001). The role of market efficiency intuitions in consumer choice: a case of compensatory

inferences. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 346 – 361.

Dawar, N., & Parker, P. (1994). Marketing universals: consumers’

use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. Journal of Marketing, 58,

81 – 95.

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of

price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 307 – 319.

Durvasula, S., Andrews, J. C., Lysonski, S., & Netemeyer, R. G.

(1993). Assessing the cross-national applicability of consumer

behavior models: a model of attitude toward advertising in general. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 626 – 636.

Fan, J. X., & Xiao, J. J. (1998). Consumer decision-making styles of

young-adult Chinese. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32(2),

275 – 294.

Gabriel, P. E., & Marsden, J. R. (1990). An examination of market

efficiency in British racetrack betting. Journal of Political Economy, 98(4), 874 – 885.

Grewal, D., Gotlieb, J., & Marmorstein, H. (1994). The moderating

effects of message framing and source credibility on the price –

perceived risk relationship. Journal of Consumer Research, 21,

145 – 153.

Hjorth-Anderson, C. (1984). The concept of quality and the efficiency of markets for consumer products. Journal of Consumer

Research, 11, 708 – 718.

Ho, S. C. (2001). Growing consumer power in China: some lessons for managers. Journal of International Marketing, 9 (1),

64 – 83.

Ho, S. C., & Sin, Y. (1988). Consumer protection in China: the

current state of the art. European Journal of Marketing, 22(1),

41 – 57.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related value. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: software of the

mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1984). Hofstede’s culture dimensions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 15(4), 417 – 433.

John, D. R., Scott, C. A., & Bettman, J. R. (1986). Sampling data

for covariation assessment: the effect of prior beliefs on search

patterns. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 149 – 154.

Lichtenstein, D. R., & Burton, S. (1989). The relationship between

perceived and objective price – quality. Journal of Marketing

Research, 26, 429 – 443.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Ridgway, N. M., & Netemeyer, R. G. (1993).

Price perceptions and consumer shopping behavior: a field

study. Journal of Marketing Research, 30, 234 – 245.

Luo, Y., & Peng, M. W. (1999). Learning to compete in a transition

economy: experience, environment, & performance. Journal of

International Business Studies, 30(2), 269 – 296.

Mandrik, C. A., Fern, E. F., & Bao, Y. (1999). Intergenerational

influence in mother/daughter dyads. Working paper. Virginia

Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological

Review, 98, 224 – 253.

McGowan, K. M., & Sternquist, B. J. (1998). Dimensions of price

as a marketing universal: a comparison of Japanese & U.S.

consumers. Journal of International Marketing, 6(4), 49 – 65.

Moschis, G. P., & Moore, R. L. (1979, September). Decision making among the young: a socialization perspective. Journal of

Consumer Research, 6, 101 – 112.

Mullen, M. R. (1995). Diagnosing measurement equivalence in

cross-national research. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 573 – 596.

Nee, V. (1992). Organizational dynamics of marketing transition:

hybrid firms, property right, and mixed economy in China. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 1 – 27.

Peterson, R. A., & Wilson, W. R. (1985). Perceived risk and price

reliance schema as price-perceived quality mediators. In J.

Jacoby, & J. C. Olson (Eds.), Perceived quality: how consumers view stores and merchandise ( pp. 247 – 268). Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company.

Phillips, L. W. (1981). Assessing measurement error in key informant reports: a methodological note on organizational analysis in

marketing. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 395 – 415.

Raju, P. S. (1980). Optimum stimulation level: its relationship to

personality, demographics, and exploratory behavior. Journal of

Consumer Research, 7(3), 272 – 282.

Rao, A. R., & Bergen, M. E. (1992). Price premium variations as a

consequence of buyers’ lack of information. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 412 – 423.

Rao, A. R., & Monroe, K. B. (1989). The effect of price, brand name,

and store name on buyers’ perceptions of product quality: an

integrative review. Journal of Marketing Research, 26, 351 – 357.

Ratchford, B. T., Agrawal, J., Grimm, P. E., & Srinivasan, N.

(1996). Toward understanding the measurement of market

efficiency. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 15(2),

167 – 184.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product

differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 34 – 55.

Shimp, T. A., & Bearden, W. O. (1982). Warranty and other extrinsic cue effects on consumers’ risk perceptions. Journal of

Consumer Research, 9, 38 – 46.

Singh, J. (1995). Measurement issues in cross-national research.

Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 597 – 619.

Steenkamp, J. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal

of Consumer Research, 25, 78 – 90.

Teas, K. R., & Agarwal, S. (2000). The effects of extrinsic

product cues on consumers’ perceptions of quality, sacrifice,

K.Z. Zhou et al. / Intern. J. of Research in Marketing 19 (2002) 349–365

and value. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (2),

278 – 290.

Tellis, G. J., & Gaeth, G. J. (1990). Best value, price-seeking, and

price aversion: the impact of information and learning on consumer choices. Journal of Marketing, 54, 34 – 45.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder,

CO: Westview Press.

365

Veeck, A., & Burns, A. C. (1995). An investigation of the use of

price-quality schema by urban Chinese consumers. Advances in

Consumer Research, 22, 297 – 302.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and

value: a means – end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal

of Marketing, 52, 2 – 22.