Accounting & Administrative Controls Handbook

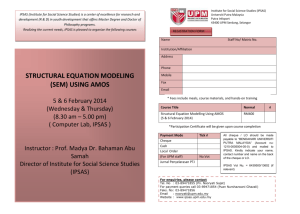

advertisement