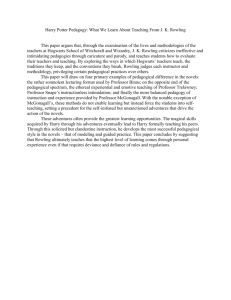

Lessons Learned: Rowling's Use of Folklore in the World of Harry

Lessons Learned:

Rowling’s

use

of

Folklore

in

the

World

of

Harry

Potter

Sammi Vanderstok

[Pick the date]

J.K.

Rowling created a fantastical world in her Harry Potter series complete with locations, history, and cultural nuances.

She gave depth to her world by having her characters face issues that people today are struggling with.

She even created historical legends and myths of the wizarding world and had her main characters interact with them.

But one interesting thing to note about Rowling’s use of wizarding legend is that in the Harry Potter series we hear more about the folklore than we do about the actual wizard history.

Instead of having her main character interact and know about past wizards or historical events, Rowling has her characters unearth old legends and discover artifacts that had only been mentioned in young wizard tales.

From Harry’s very first adventure in Harry Potter and the

Sorcerer’s Stone until his final quest to destroy Voldemort, wizarding legends offer solutions, literally, to

Harry and his quests.

In seeing how Rowling puts so much emphasis on wizarding lore, it is my belief that she is expressing an opinion that the moral messages gained from folklore are more important than the actual history of a society.

There may be various reasons why J.K.

Rowling put so much emphasis on developing a mythological past for her wizarding world.

It could be that Rowling wanted to include some heart ‐ warming tales that reminded her young adult audience of their childhood stories.

Or it could be that

Rowling wanted to create a mystery that her young heroes would be familiar with.

It is even possible that the lack of historical presence and heavy reliance on folklore in her series was an unconscious oversight.

But seeing the extensive nature folklore has in the Harry Potter series, it seems that the above explanations are too simple to cover the importance of her choice.

One reason that Rowling may have chose myths to teach her characters lessons is that myths, in essence, are universal truths.

Myths and folklore are thought to be figurative stories about how people within different cultures deal with certain universal life issues;

1

every culture has them, and it is one of

1

Susan Sellers, “Contexts: Theories of Myth,” in Myth and Fairy Tale in Contemporary Women’s Fiction ( New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2001), http://site.ebrary.com.online.library.marist.edu/lib/marist/docDetail.action?docID=10057407&p00=myths%2C%20fairy%20tales%2C%20%20fe minism (accessed May 2, 2010), p.4.

Page 2 of 13

the influences that shape how a society sees the world and understands their cultural traditions.

There are many different theories as to the purpose and importance of myths for human beings, but myths are almost universally acknowledged as a tool in helping to figure out the world and each other.

Joseph Campbell, a literary analyst who has done extensive research about the structure of mythology and specifically the hero ‐ quest, discusses the importance of mythology in a society in The

Power of Myth .

In the book, he argues that “myths are [the] clues to the spiritual potentialities of the human life.

[They show] what we’re capable of knowing and experiencing within.”

2

He then goes onto say that myths “have to do with the themes that have supported human life, built civilizations, and informed religions over a millennia, [they] have to do with deep inner problems, inner mysteries, inner thresholds of passage.”

3

According to Campbell, myths are a form of literature that deals with universal issues.

He saw them as central to human kind and their desire to live an enlightened life.

He even goes onto state that myths are there to provide insight and answers to universal issues.

He says that the value of a myth is that they help the present generation learn from the past and he evens issues a warning to the reader that “if you don’t know what the guide ‐ signs are along the way, you have to work it out yourself.”

4

Carl Jung, a man who researched and tested a lot of psychoanalytic ideas and also contributed his concept of archetypes to literary analysis.

5

Jung, like Campbell, continues on a similar thread and states that myths “offer crucial messages, providing insights into unrealized or neglected aspects of personality, and issue warnings of imbalance or wrong action.”

6

In considering what both of these

2

Joseph Cambell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, ed.

Betty Sue Flowers (New York: Anchor Books, 1988), p.

5.

3

Joseph Cambell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, ed.

Betty Sue Flowers (New York: Anchor Books, 1988), p.

2.

4

Joseph Cambell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, ed.

Betty Sue Flowers (New York: Anchor Books, 1988), p.

2.

5

Susan Sellers, “Contexts: Theories of Myth,” in Myth and Fairy Tale in Contemporary Women’s Fiction ( New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2001), http://site.ebrary.com.online.library.marist.edu/lib/marist/docDetail.action?docID=10057407&p00=myths%2C%20fairy%20tales%2C%20%20fe minism (accessed May 2, 2010), p.4.

6

Susan Sellers, “Contexts: Theories of Myth,” in Myth and Fairy Tale in Contemporary Women’s Fiction ( New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2001), http://site.ebrary.com.online.library.marist.edu/lib/marist/docDetail.action?docID=10057407&p00=myths%2C%20fairy%20tales%2C%20%20fe minism (accessed May 2, 2010), p.

5.

Page 3 of 13

theorists were stating, it seems that the true meaning and value of a culture’s myths are indeed the lesson that are at the heart of the tale.

One example of Rowling emphasizing the morals within her fairy ‐ tales is in how she wrote The

Tales of Beedle the Bard.

This book is one of the few accompanying texts that Rowling wrote about the wizarding world of Harry Potter, and it is remarkable that she chose to write about wizarding fairy tales instead of the plentiful array of other wizarding issues.

Then, she created the book in such a way that it includes the literary analysis of each story by her most wise character, Albus Dumbledore.

She could have just as easily simply made a collection of wizarding fairy tales for readers to enjoy, but the fact that she includes the insights of the most respected and moral wizard, Dumbledore, shows that she is trying to impart the value of the fairy tales more than the actual stories themselves.

For example, in Dumbledore’s commentary on “The Wizard and the Hopping Pot,” which is a pro ‐ muggle fairy tale, he says “a simple and heart ‐ warming fable, one might think—in which case, one would reveal oneself to be an innocent nincompoop.”

7

Dumbledore goes onto explain that the pro ‐

Muggle fairy tale that taught the message of brotherly love between wizards and muggles was nothing short of miraculous because wizards have practically been at war with non ‐ wizards for over five centuries.

8

How wizards should co ‐ exist with the larger non ‐ magical society is the backdrop for the entire Harry Potter series and as the reader learns more about the wizarding world, the more they see the issue of superiority and inferiority come up in terms of how much muggle blood one has in their ancestry.

Considering how contentious the issue “The Wizard and the Hopping Pot” is dealing with, and considering the fact that it leaves the reader with a clear moral to embody, one can see that this fairy tale is definitely beyond “simple and heart ‐ warming.”

9

It is relating a truth that can bring peace to wizarding world while being conveyed through a medium that will exist for generations to come.

Seeing

7

J.

K.

Rowling, “The Wizard and the Hopping Pot” in The Tales of Beedle the Bard (New York: the Children’s High Level Group, 2008), p.11.

8

J.

K.

Rowling, “The Wizard and the Hopping Pot” in The Tales of Beedle the Bard (New York: the Children’s High Level Group, 2008), p.12.

9

J.

K.

Rowling, “The Wizard and the Hopping Pot” in The Tales of Beedle the Bard (New York: the Children’s High Level Group, 2008), p.11.

Page 4 of 13

how this myth and its message have reached the ears of countless witches and wizards, it would make sense that Rowling would want to identify this large influence and magnify it.

Another reason why Rowling could be trying to convey a message through her use of myth instead of history has to do with how the British society in general views their folklore and mythology.

In

2008 there was a survey done by a local British newspaper asking which British characters, such as

Winston Churchill and Sherlock Holmes, were real and which were fictitious.

Surprisingly, the survey revealed that over 50% of the people believed that Sherlock Holmes was real and almost 25% believed that Winston Churchill and Florence Nightingale were mythological.

10

There was also an equal amount of confusion between the real kings of British past like Richard the Lionheart, and fictitious kings like King

Arthur.

People were even unsure about the reality of fairly internationally known characters like Gandhi and Cleopatra.

11

Of course it is hard to judge whether or not this survey was completely representative of the entire British nation, but it does bring up an interesting point.

How much influence has British folklore had upon how the British view their own past?

British history, like the history of almost every nation, is a mixture of good governance and tyrannical rulers, of national progression and the brutal conquest of foreign lands, and of national identity mixed in with the repression of other cultures.

Although there are of course noteworthy characters in England’s past like Sir Isaac Newton (discovered gravity), William

Wilberforce (politician who headed the abolition of slavery in England) and William Shakespeare,

12

there are also countless examples of immoral leaders who used their power to a negative effect.

So if, for example, a parent was faced with having to use a British historical figure as a role model for their child,

10

“Legendary figures are just myths,” Aberdeen Evening Express , February 4, 2008, p.

8, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://proquest.umi.com.online.library.marist.edu/pqdweb?did=1423699671&sid=1&Fmt=3&clientI d=14836&RQT=309&VName=PQD (accessed May 5, 2010).

11

“Legendary figures are just myths,” Aberdeen Evening Express , February 4, 2008, p.

8, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://proquest.umi.com.online.library.marist.edu/pqdweb?did=1423699671&sid=1&Fmt=3&clientI d=14836&RQT=309&VName=PQD (accessed May 5, 2010).

12

Encyclopedia of the Nations, “Famous Britons” in United Kingdom, Advameg Inc., http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Europe/United ‐ Kingdom ‐ FAMOUS ‐ BRITONS.html

(accessed May 9, 2010).

Page 5 of 13

how many of them would ever tell their child to be like King Henry VIII

13

?

If they did, they would be encouraging violence as a means of control, the misuse of women, and the execution of whoever you don’t like.

In many ways, it is much easier to gleam life lessons from the British legends than it is to try to find the heroic deeds of past British rulers.

It could be that the un ‐ romantic reality of British history is one reason why British culture has long romanticized its mythological heroes.

In trying to guide the future generations to make honorable and selfless choices, it would be easier to point their youth to myths like the legend of King Arthur and his adventures to create the British Empire than any one historical ruler.

And indeed, from the 10 th

century on, there have been countless references and stories done on King Arthur and all the quests he went on.

14

There are even parts of England that claim to be a part of the Arthurian legend, like the city of Glastonbury which claims to be the burial site of Arthur and Guinevere, and Cadbury Castle in

Somerset which claims to be where Camelot was.

15

There have been princes named after him, King

Henry VII named his eldest son Arthur, and King Arthur’s Round Table became synonymous with how medieval England conducted its court and activities like their tournaments.

16

We also see how much influence it has had on popular culture with all the books and movies that have explored the Arthurian legend over the centuries.

So why would we see the legends of Arthur pop ‐ up time and again in British culture?

Not because it is the literal past of the country, because indeed it is not, but because Arthur was a symbol of what they wanted their culture to be like.

If one compares how England focuses so much on its legendary past to how Rowling develops the wizarding world’s folklore, one will find a lot of common ground.

In her series, Rowling depicts wizard history much like the actual history of Great Britain—extremely muddled and hard to learn from.

13

Anniina Jokinen, “King Henry VIII of England” in Luminarium:Anthology of English Literature, http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/tudorbio.htm

(accessed May 9, 2010).

14

15

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, ed.

Lewis Thorpe (London: Penguin Classics, 1966), p.107.

Norris J.

Lacy et al, ed., “Topography and Local Legends” in The New Arthurian Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1996), p.455.

16

Norris J.

Lacy et al, ed., “Tournaments” in The New Arthurian Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1996), p.458.

Page 6 of 13

In The Tales of Beedle the Bard , Dumbledore mentions some of the dark sides of wizarding past and how medieval wizards used to use the Unforgivable Curses when dueling each other.

17

We also hear the occasional mention of dark wizards and some of the gruesome things they did in history throughout the

Harry Potter series, like invent Horcruxes

18

.

Seeing how Rowling parallels wizarding history with British history could also explain why Rowling makes very little effort to have her characters be knowledgeable about wizarding history.

One of the best examples of this is how she develops the character of Ron Weasley.

All throughout the Harry Potter series Ron remains ignorant of wizarding history and the only knowledge he seems to retain is the childhood stories that he grew up with.

He is dependent upon Hermoine’s instruction for his entire duration at Hogwart’s and when Ron recognizes The Tales of Beedle the Bard in the final Harry Potter book, Harry comments that “the circumstance of Ron having read a book that

Hermione had not was unprecedented.”

19

Of course this quote is also referring to Ron’s level of literacy, but it also shows why Ron is so uninformed about wizarding history—he has no desire to learn or study the ancient past.

But not only in Ron is the apparent ignorance of history strong, Rowling seems to put history in a secondary role throughout her entire wizarding world.

Its importance never seems to leave the classroom, and Hermione ends up being the main exception to the rule that no one seems to care about wizarding history once they leave school.

But if one considers the theory that Rowling is stating that the lessons learned in history are more important than remembering the actual history itself, then her apparent disregard for history begins to make sense.

17

J.

K.

Rowling, “Babbitty Rabbitty and Her Cackling Stump” in The Tales of Beedle the Bard (New York: the Children’s High Level Group,

2008), p.86.

18

19

J.K.

Rowling, Harry Potter and the Half ‐ Blood Prince , (New York: Scholastic Inc., 2005), p.

497.

J.K.

Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows , (New York: Scholastic Inc., 2007), p.135.

Page 7 of 13

It is also important to note that Rowling’s writings have been directly influenced and based off of British mythology.

According to the Encyclopedia of Arthurian Legend, “common elements in

Arthurian fantasy are a young protagonist assisted by siblings or friends, a quest to acquire magical artifacts, a supernatural guide, a confrontation between good and evil in which the child plays a crucial role, and a good deal of folklore associated with the “Old Ones.”

20

This description in particular is surprising because it sounds almost exactly like the story line of the Harry Potter series.

If one analyzes

Harry Potter even briefly, one will see similarities in how Harry is the prophesied to bring peace to the wizards like how Arthur is prophesized to bring peace to Britain.

21

There are also similarities between

Merlin and Dumbledore and Harry’s ever ‐ present quests throughout the series.

But not only does Rowling create a story in line with Arthurian myths, she completely bases her work off of England’s mythological characters and creatures.

Her entire series is about witches, wizards, and the magical world they’re a part of.

More specifically, the way she develops her fantastical world is in line with how the British viewed magic in their mythological past.

She has her characters interact with

Western magical creatures like the basilisk, the dragon, the giant, the unicorn, the elf, and the centaur.

She has her heroes go on quests for magical objects like the Philosopher’s Stone while having them use magical artifacts like time ‐ travelling necklaces.

Seeing how Rowling directly drew upon England’s mythological history, one would assume that she herself noticed what power mythology holds in influencing people.

The final reason why it seems that Rowling is stating that mythology supersedes the past is because another famous British author, J.R.R.

Tolkien, wrote his novels for this exact purpose.

When

Tolkien was asked about why he created the Lord of the Rings series, he wrote a letter explaining that

20

Norris J.

Lacy et al, ed., “Juvenile Fiction in English” in The New Arthurian Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1996), p.257.

21

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, ed.

Lewis Thorpe (London: Penguin Classics, 1966), p.92.

Page 8 of 13

his goal behind creating Middle Earth was to create a mythology that Britain could claim as its own.

22

In later letters, Tolkien espoused this idea even more clearly as he wrote that he hoped his Middle ‐ Earth mythology could guide England for centuries to come in ways the existing mythology could not.

23

If one reads Tolkien’s works, especially his book of Middle ‐ Earth mythology called The Simillarion, one can see how he does indeed establish a complete mythology.

He compiles almost every form of myth starting from the Creation of Middle ‐ Earth to the famous heroes who sacrificed themselves for the sake of peace in the lands.

24

When trying to explain why he felt he needed to develop mythology, Tolkien replied that “myth and fairy ‐ story…must reflect and contain in solution, elements of moral and religious truth (or error), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary real world.”

25

Tolkien believed that mythology was critical in trying to guide people towards a better future.

He saw the value of including a mythology within the history of a country because it offered examples of how future generations should act and think.

Once again this topic can be explored in much more depth, but even in these short quotes one can see that Tolkien exercised his created mythology to guide his characters, and in his case took this idea to a new level by hoping that his created mythology would guide all of Great Britain.

One interesting thing though is when Rowling herself was asked by interviewers whether she was influenced by Tolkien, she responded that “if you set aside the fact that the books overlap in terms of dragons & wands & wizards, the Harry Potter books are very different, especially in tone.

Tolkien created a whole mythology; I don’t think anyone could claim that I have done that.

On the other

22

John C.

Hunter, The Evidentce of Things Not Seen, Journal of Modern Literature (Winter 2006), volume 29 ‐ 2, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2006530679&site=ehost ‐ live , p128 and 136.

23

John C.

Hunter, The Evidentce of Things Not Seen, Journal of Modern Literature (Winter 2006), volume 29 ‐ 2, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2006530679&site=ehost ‐ live , p.136.

24

25

Jane Chance, Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader (Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), p.

20.

John Gough, Tolkien’s Creation Myth in the Simillarion: Northern or Not?, Children’s Literature in Education, published March 1999,

Volume 30 ‐ 1, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=1999028365&site=ehost ‐ live , p.3.

Page 9 of 13

hand…he didn’t have Dudley.”

26

But although Rowling may not have received inspiration from Tolkien in terms of her plot and characters, and as she says, didn’t develop an entirely new mythology, it seems that on a deeper level she did mimic how Tolkien used mythology as a moral compass.

One example is that Rowling, like Tolkien, has her characters refer back to folklore and myths in order to seek guidance.

In J.R.R

Tolkien’s writings he not only takes time to create an in depth mythology, there are numerous scenes in his Lord of the Rings trilogy where one of the characters refers back to the ancient legends of the land and feel inspiration to continue on.

One scene in particular is when Samwise and Frodo are on their journey to Mordor and losing faith that they can succeed, when Samwise jumps into an approximate 20 page retelling of the history of one of Middle ‐ Earth’s hero’s called Hurin.

27

If one then takes this example and looks at how Rowling inspires and guides her characters, a lot of similarities surface.

One of the largest examples of how Rowling uses folklore to guide her characters is how she framed the downfall of Voldemort.

In the beginning of the Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,

Dumbledore leaves Hermione The Tales of Beedle the Bard which has the story “ The Tale of the Three

Brothers.” In the story, the reader finds out about the legend of the Elder Wand and how it supposedly is makes the wielder undefeatable.

But at the end of the story the brother who owns the elder wand dies and the moral is that can never beat off death and seeking to do so will always end in tragedy.

The interesting thing is that of all the ways that Voldemort could have been defeated, it is his disregard for the moral of a story that ultimately leads to his downfall.

What’s even more interesting is that Rowling doesn’t only make Harry the hero because of his duel with Voldemort, but she includes how Harry learns the lesson from “The Tales of the Three Brothers” and handles the three Hallows in the proper way.

Harry takes to heart that one can never fool death and as such he is able to resist the

26

John Granger, “Tolkien and Rowling: A Case for “Text Only”, Deathly Hallows Lectures (October 9, 2008) http://www.hogwartsprofessor.com/tolkien ‐ and ‐ rowling ‐ a ‐ case ‐ for ‐ text ‐ only/ (accessed May 10, 2010).

27

J.R.R.

Tolkien, The Return of the King (New York: Ballantine Publishers, 1965), p.221.

Page 10 of 13

temptation the Resurrection Stone and Elder Wand offer.

The last few pages of the seventh book

(before the epilogue) end with Harry deciding to never use the Elder Wand and as such he breaks the deadly cycle it had begun in its legendary past.

28

Having the Harry Potter series end in this way is very dramatic and like Tolkien’s emphasis on mythology, Rowling solidifies the use of legends as a moral compass.

One final point that one should notice is that Rowling takes artistic license with her own mythology and turns wizarding myths into real wizarding history.

She creates the legend of the Chamber of Secrets and then has it become the actual location of Voldemort’s 2 nd

attempt to return to power.

She takes the Deathly Hallows and makes their presence real and vital for defeating evil.

Then, she takes real historical artifacts of the wizarding world and gives them legendary qualities.

The 4 artifacts of the

Hogwart’s founders either become Horcruxes or become one of the few weapons that can destroy the

Horcruxes, like Gryffindor’s sword.

If we then think about what effect her blending of legend and reality produce, one can see that the purpose of the legend becomes more magnified.

The Chamber of Secrets is supposed to fulfill Slytherin’s goal of purging the school of un ‐ pure wizards and by making Voldemort actually access the place, the purpose of Slytherin becomes embodied.

The point of the Deathly Hallows is to teach children that death should never be evaded or meddled with and when they become real, the purpose of the story becomes the solution to stopping

Voldemort.

The four artifacts of the Hogwart’s founders not only symbolize the four houses, but when all of them are united then the school can remain whole and prosperous, and Harry has to discover and utilize every one of them to stop Voldemort.

Considering that Rowling’s personification of wizarding legends seem to lead to the moral of the legend also becoming literal, it seems that Rowling was indeed trying to convey the message of morals being the actual lesson of an event.

28

J.K.

Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows , (New York: Scholastic Inc., 2007), p.749.

Page 11 of 13

In considering the impact J.K.

Rowling has had upon this generation’s young people, it is important to not only notice the new trends and styles she has created through her literary writings; it is also important to notice the morals and messages she is conveying and supporting.

Through her characters she is encouraging her audience to adopt a certain worldview and to live by a certain moral standard, and it seems that she is trying to tell her reader to look to the past to find guidance for the future.

But more specifically, Rowling is saying that one’s myths, legends, and fairy tales are the embodiment of what our past has to offer to our present generation; that within these lay the truths that will guide our society and its members in the right direction.

Historically, children’s literature has been a tool for educating the youth and it seems that

Rowling’s Harry Potter series is no exception to this trend.

Seeing her utilize mythology in a way that magnified her world and specifically magnified the messages she was trying to convey was and is truly noteworthy.

In considering all of the messages that Rowling shares through her Harry Potter series, it seems that she is encouraging our future generation to never forget that society will only prevail if we take to heart the lessons our culture has taught us through the legends they left behind.

Page 12 of 13

Works

Cited

Campbell, Joseph with Moyers,Bill.

The Power of Myth .

Edited by Betty Sue Flowers.

New York: Anchor

Books, 1988.

Chance, Jane.

Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader.

Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky,

2004.

Encyclopedia of the Nations.

“Famous Britons” in United Kingdom.

Advameg Inc.

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Europe/United ‐ Kingdom ‐ FAMOUS ‐ BRITONS.html

(accessed May

9, 2010).

Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The History of the Kings of Britain.

Edited by Lewis Thorpe.

London: Penguin

Classics, 1966.

Gough, John.

Tolkien’s Creation Myth in the Simillarion: Northern or Not?

Children’s Literature in

Education, published March 1999, Volume 30 ‐ 1, http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh

&AN=1999028365&site=ehost ‐ live , (accesses May 10, 2010).

Granger, John.

“Tolkien and Rowling: A Case for “Text Only”, Deathly Hallows Lectures on October 9,

2008.

http://www.hogwartsprofessor.com/tolkien ‐ and ‐ rowling ‐ a ‐ case ‐ for ‐ text ‐ only/ (accessed May 10,

2010).

Hunter,John C.

The Evidence of Things Not Seen, Journal of Modern Literature (Winter 2006), volume 29 ‐

2, p.

128 ‐ 47.

http://online.library.marist.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh

&AN=2006530679&site=ehost ‐ live (accessed May 7, 2010).

Jokinen, Anniina.

“King Henry VIII of England” in Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature.

Anniina

Jokinen.

http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/tudorbio.htm

(accessed May 9, 2010).

Lacy, Norris J.

ed., Ashe, Geoffrey ed., Ihle Sandra Ness ed., Kalinke, Marianne E.

ed., and Thompson,

Raymond H.

ed..

The New Arthurian Encyclopedia.

New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1996.

"

Legendary figures are just myths.

" Aberdeen Evening Express 4 Feb.

2008, ProQuest

Newsstand, ProQuest.

Web.

11 May.

2010.

Rowling, J.K..

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

New York: Scholastic Inc., 2007.

Rowling, J.K..

Harry Potter and the Half ‐ Blood Prince.

New York: Scholastic Inc., 2005.

Rowling, J.K..

The Tales of Beedle the Bard.

New York: Children’s High Level Group, 2008.

Sellers, Susan.

“Contexts: Theories of Myth.” In Myth and Fairy Tale in Contemporary Women’s Fiction.

New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

http://site.ebrary.com.online.library.marist.edu/lib/marist/docDetail.action?docID=10057407&p00=myt hs%2C%20fairy%20tales%2C%20%20feminism .

Tolkien, J.R.R..

The Return of the King .

New York: Ballantine Publishers, 1965.

Page 13 of 13