Ghost: Beliefs, History & Cultural Significance

advertisement

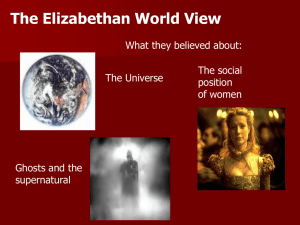

Ghost From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In traditional belief, a ghost is the soul or spirit of a deceased person or animal that can appear, in visible form or other manifestation, to the living. Descriptions of the apparition of ghosts can vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or wispy shapes, to realistic, life-like visions. The deliberate attempt to contact the spirit of a deceased person is known as necromancy, or in spiritism as a séance. The belief in manifestations of the spirits of the dead is widespread, dating back to animism or ancestor worship in pre-literate cultures. Certain religious practices—funeral rites, exorcisms, and some practices of spiritualism and ritual magic—are specifically designed to appease the spirits of the dead. Ghosts are generally described as solitary essences that haunt particular locations, objects, or people they were associated with in life Besides denoting the human spirit or soul, both of the living and the deceased, the Old English word is used as a synonym of Latin spiritus also in the meaning of "breath" or "blast" from the earliest attestations (9th century). It could also denote any good or evil spirit, i.e. angels and demons; the Anglo-Saxon gospel refers to the demonic possession of Matthew 12:43 as se unclæna gast. Also from the Old English period, the word could denote the spirit of God, viz. the "Holy Ghost". The now prevailing sense of "the soul of a deceased person, spoken of as appearing in a visible form" only emerges in Middle English (14th century). The modern noun does, however, retain a wider field of application, extending on one hand to "soul", "spirit", "mind" or "psyche", the seat of feeling, thought and moral judgment; on the other hand used figuratively of any shadowy outline, fuzzy or unsubstantial image, in optics, photography and cinematography especially a flare, secondary image or spurious signal. In many cultures malignant, restless ghosts are distinguished from the more benign spirits involved in ancestor worship. Ancestor worship typically involves rites intended to prevent vengeful spirits of the dead, imagined as starving and envious of the living. Strategies for preventing these spirits may either include sacrifice, i.e., giving the dead food and drink to pacify them, or magical banishment of the deceased to force them not to return. Ritual feeding of the dead is performed in traditions like the Chinese Ghost Festival or the Western All Soul’s Day. Magical banishment of the dead is present in many of the world's burial customs. The bodies found in many tumuli (kurgan) had been ritually bound before burial, and the custom of binding the dead persists, for example, in rural Anatolia. Although the human soul was sometimes symbolically or literally depicted in ancient cultures as a bird or other animal, it appears to have been widely held that the soul was an exact reproduction of the body in every feature, even down to clothing the person wore. This is depicted in artwork from various ancient cultures, including such works as the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which shows deceased people in the afterlife appearing much as they did before death, including the style of dress. Another widespread belief concerning ghosts is that they are composed of a misty, airy, or subtle material. Anthropologists link this idea to early beliefs that ghosts were the person within the person (the person's spirit), most noticeable in ancient cultures as a person's breath, which upon exhaling in colder climates appears visibly as a white mist. This belief may have also fostered the metaphorical meaning of "breath" in certain languages, such as the Latin spiritus and the Greek pneuma, which by analogy became extended to mean the soul. In the Bible, God is depicted as animating Adam with a breath. In many traditional accounts, ghosts were often thought to be deceased people looking for vengeance, or imprisoned on earth for bad things they did during life. The appearance of a ghost has often been regarded as an omen or portent of death. Seeing one's own ghostly double or "fetch" is a related omen of death. White ladies were reported to appear in many rural areas, and supposed to have died tragically or suffered trauma in life. White Lady legends are found around the world. Common to many of them is the theme of losing or being betrayed by a husband or fiancé. They are often associated with an individual family line or regarded as a harbinger of death similar to a banshee. Legends of ghost ships have existed since the 18th century; most notable of these is the Flying Dutchman. This theme has been used in literature in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge. A place where ghosts are reported is described as haunted, and often seen as being inhabited by spirits of deceased who may have been former residents or were familiar with the property. Supernatural activity inside homes is said to be mainly associated with violent or tragic events in the building's past such as murder, accidental death, or suicide — sometimes in the recent or ancient past. But not all hauntings are at a place of a violent death, or even on violent grounds. Many cultures and religions believe the essence of a being, such as the 'soul', continues to exist. Some philosophical and religious views argue that the 'spirits' of those who have died have not 'passed over' and are trapped inside the property where their memories and energy are strong. There was widespread belief in ghosts in ancient Egyptian culture in the sense of the continued existence of the soul and spirit after death, with the ability to assist or harm the living, and the possibility of a second death. Over a period of more than 2,500 years, Egyptian beliefs about the nature of the afterlife evolved constantly. Many of these beliefs were recorded in inscriptions, papyrus scrolls and tomb paintings. The Egyptian Book of the Dead compiles some of the beliefs from different periods of ancient Egyptian history. In modern times, the fanciful concept of a mummy coming back to life and wreaking vengeance when disturbed has spawned a whole genre of horror stories and movies. Biblical references & Judæo–Christian belief The Hebrew Torah and the Bible contain few references to ghosts, associating spiritism with forbidden occult activities cf. Deuteronomy 18:11. The most notable reference is in the First Book of Samuel (I Samuel 28:3-19 KJV), in which a disguised King Saul has the Witch of Endor summon the spirit/ghost of Samuel. In the New Testament, Jesus has to persuade the Disciples that he is not a ghost following the resurrection, Luke 24:37-39 (note that some versions of the Bible, such as the KJV and NKJV, use the term "spirit"). In a similar vein, Jesus' followers at first believe him to be a ghost (spirit) when they see him walking on water. In several cases, the Bible excludes ghosts, in the modern sense, from being associated with the dead. The general argument of these cases is that in death, there is a cessation of all consciousness, effectively the non-existence of the identity. A representative case is found in Ecclesiastes 9:5,6. This must not be understood that there is no afterlife, only that there is a time lapse between the resurrection and death, during which there is a period of non-existence. As such, much of the Christian Church considers ghosts as beings who while tied to earth, no longer live on the material plane. Furthermore, some Christian denominations teach that ghosts are beings who linger in an interim state before continuing their journey to heaven. On occasion, God would allow the souls in this state to return to earth to warn the living of the need for repentance. Nevertheless, Jews and Christians are taught that it is sinful to attempt to conjure or control spirits, in accordance with Deuteronomy XVIII: 9–12. Accepting, but moving beyond this position, some ghosts are actually said to be demons in disguise, who the Church teaches, in accordance with I Timothy 4:1, that they "come to deceive people and draw them away from God and into bondage." As a result, attempts to contact the dead may lead to unwanted contact with a demon or an unclean spirit, as was said to occur in the case of Robbie Mannheim, a fourteen year old Maryland youth. According to one Christian source, appearances of orbs of light that are attributed by some authors to ghosts, can be explained by II Corinthians 11:14, which states that "even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light" (NRSV). Classical Greece Ghosts appeared in Homer's Odyssey and Iliad, in which they were described as vanishing "as a vapor, gibbering and whining into the earth". Homer’s ghosts had little interaction with the world of the living. Periodically they were called upon to provide advice or prophecy, but they do not appear to be particularly feared. Ghosts in the classical world often appeared in the form of vapor or smoke, but at other times they were described as being substantial, appearing as they had been at the time of death, complete with the wounds that killed them. By the 5th century BC, classical Greek ghosts had become haunting, frightening creatures who could work to either good or evil purposes. The spirit of the dead was believed to hover near the resting place of the corpse, and cemeteries were places the living avoided. The dead were to be ritually mourned through public ceremony, sacrifice and libations, or they might return to haunt their families. The ancient Greeks held annual feasts to honor and placate the spirits of the dead, to which the family ghosts were invited, and after which they were “firmly invited to leave until the same time next year”. The 5th century BC play Oresteia contains one of the first ghosts to appear in a work of fiction. Roman Empire The ancient Romans believed a ghost could be used to exact revenge on an enemy by scratching a curse on a piece of lead or pottery and placing it into a grave. Plutarch, in the 1st century AD, described the haunting of the baths at Chaeronea by the ghost of a murdered man. The ghost’s loud and frightful groans caused the people of the town to seal up the doors of the building. Another celebrated account of a haunted house from the ancient classical world is given by Pliny the Younger (c. 50 AD). Pliny describes the haunting of a house in Athens by a ghost bound in chains. The hauntings ceased when the ghost's shackled skeleton was unearthed, and given a proper reburial. The writers Plautus and Lucian also wrote stories about haunted houses. One of the first persons to express disbelief in ghosts was Lucian of Samosata in the 2nd century AD. In his tale "The Doubter" (circa 150 AD) he relates how Democritus "the learned man from Abdera in Thrace" lived in a tomb outside the city gates to prove that cemeteries were not haunted by the spirits of the departed. Lucian relates how he persisted in his disbelief despite practical jokes perpetrated by "some young men of Abdera" who dressed up in black robes with skull masks to frighten him. This account by Lucian notes something about the popular classical expectation of how a ghost should look. In the 5th century AD, the Christian priest Constantius of Lyon recorded an instance of the recurring theme of the improperly buried dead who come back to haunt the living, and who can only cease their haunting when their bones have been discovered and properly reburied. European Middle Ages Ghosts reported in medieval Europe tended to fall into two categories: the souls of the dead, or demons. The souls of the dead returned for a specific purpose. Demonic ghosts existed only to torment or tempt the living. The living could tell them apart by demanding their purpose in the name of Jesus Christ. The soul of a dead person divulged their mission, while a demonic ghost was banished at the sound of the Holy Name. Most ghosts were souls assigned to Purgatory, condemned for a specific period to atone for their transgressions in life. Their penance was generally related to their sin. For example, the ghost of a man who had been abusive to his servants was condemned to tear off and swallow bits of his own tongue; the ghost of another man, who had neglected to leave his cloak to the poor, was condemned to wear the cloak, now "heavy as a church tower". These ghosts appeared to the living to ask for prayers to end their suffering. Other dead souls returned to urge the living to confess their sins before their own deaths. Medieval European ghosts were more substantial than ghosts described in the Victorian age, and there are accounts of ghosts being wrestled with and physically restrained until a priest could arrive to hear its confession. Some were less solid, and could move through walls. Often they were described as paler and sadder versions of the person they had been while alive, and dressed in tattered gray rags. The vast majority of reported sightings were male. There were some reported cases of ghostly armies, fighting battles at night in the forest, or in the remains of an Iron Age hillfort, as at Wandlebury, near Cambridge, England. Living knights were sometimes challenged to single combat by phantom knights, which vanished when defeated. From the medieval period an apparition of a ghost is recorded from 1211, at the time of the Albigensian Crusade. Gervase of Tilbury, Marshal of Arles, wrote that the image of Guilhem, a boy recently murdered in the forest, appeared in his cousin's home in Beaucaire, near Avignon. This series of "visits" lasted all of the summer. Through his cousin, who spoke for him, the boy allegedly held conversations with anyone who wished, until the local priest requested to speak to the boy directly, leading to an extended disquisition on theology. The boy narrated the trauma of death and the unhappiness of his fellow souls in Purgatory, and reported that God was most pleased with the ongoing Crusade against the Cathar heretics, launched three years earlier. The time of the Albigensian Crusade in southern France was marked by intense and prolonged warfare, this constant bloodshed and dislocation of populations being the context for these reported visits by the murdered boy. European Renaissance to Romanticism "Hamlet and his father's ghost" by Henry Fuseli (1780s drawing). The ghost is wearing stylized plate armor in 17th century style, including a morion type helmet and tassets. Depicting ghosts as wearing armor, to suggest a sense of antiquity, was common in Elizabethan theater. Renaissance magic took a revived interest in the occult, including necromancy. In the era of the Reformation and Counter Reformation, there was frequently a backlash against unwholesome interest in the dark arts, typified by writers such as Thomas Erastus. The Swiss Reformed pastor Ludwig Lavater supplied one of the most frequently reprinted books of the period with his Of Ghosts and Spirits Walking By Night. The Child ballad "Sweet William's Ghost" (1868) recounts the story of a ghost returning to beg a woman to free him from his promise to marry her, as he obviously cannot being dead. Her refusal would mean his damnation. This reflects a popular British belief that the dead haunted their lovers if they took up with a new love without some formal release. "The Unquiet Grave" expresses a belief even more widespread, found in various locations over Europe: ghosts can stem from the excessive grief of the living, whose mourning interferes with the dead's peaceful rest. In many folktales from around the world, the hero arranges for the burial of a dead man. Soon after, he gains a companion who aids him and, in the end, the hero's companion reveals that he is in fact the dead man. Instances of this include the Italian fairy tale "Fair Brow" and the Swedish "The Bird 'Grip'". Scientific skepticism Joe Nickell of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, wrote that there was no credible scientific evidence that any location was inhabited by spirits of the dead. Limitations of human perception and ordinary physical explanations can account for ghost sightings; for example, air pressure changes in a home causing doors to slam, or lights from a passing car reflected through a window at night. Pareidolia, an innate tendency to recognize patterns in random perceptions, is what some skeptics believe causes people to believe that they have seen ghosts. Reports of ghosts "seen out of the corner of the eye" may be accounted for by the sensitivity of human peripheral vision. According to Nickell, peripheral vision can easily mislead, especially late at night when the brain is tired and more likely to misinterpret sights and sounds." Some researchers, such as Michael Persinger of Laurentian University, Canada, have speculated that changes in geomagnetic fields (created, e.g., by tectonic stresses in the Earth's crust or solar activity) could stimulate the brain's temporal lobes and produce many of the experiences associated with hauntings. Sound is thought to be another cause of supposed sightings. Richard Lord and Richard Wiseman have concluded that infrasound can cause humans to experience bizarre feelings in a room, such as anxiety, extreme sorrow, a feeling of being watched, or even the chills. Carbon monoxide poisoning, which can cause changes in perception of the visual and auditory systems, was speculated upon as a possible explanation for haunted houses as early as 1921. European folklore Further information: Revenant (folklore), Necromancy, Samhain, Halloween, and All Souls' Day Belief in ghosts in European folklore is characterized by the recurring fear of "returning" or revenant deceased who may harm the living. This includes the Scandinavian gjenganger, the Romanian strigoi, the Serbian vampir, the Greek vrykolakas, etc. British folklore is particularly notable for its numerous haunted locations. Belief in the soul and an afterlife remained near universal until the emergence of atheism in the 18th century. In the 19th century, spiritism resurrected "belief in ghosts" as the object of systematic inquiry, and popular opinion in Western culture remains divided. Depiction in the arts: Renaissance to Romanticism (1500 to 1840) 19th century etching by John Leech of the Ghost of Christmas Present as depicted in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol One of the more recognizable ghosts in English literature is the shade of Hamlet's murdered father in Shakespeare’s The Tragical History of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. In Hamlet, it is the ghost who demands that Prince Hamlet investigate his "murder most foul" and seek revenge upon his usurping uncle, King Claudius. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the murdered Banquo returns as a ghost to the dismay of the title character. In English Renaissance theater, ghosts were often depicted in the garb of the living and even in armor, as with the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Armor, being out-of-date by the time of the Renaissance, gave the stage ghost a sense of antiquity.[79] But the sheeted ghost began to gain ground on stage in the 19th century because an armored ghost could not satisfactorily convey the requisite spookiness: it clanked and creaked, and had to be moved about by complicated pulley systems or elevators. These clanking ghosts being hoisted about the stage became objects of ridicule as they became clichéd stage elements. Ann Jones and Peter Stallybrass, in Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory, point out, "In fact, it is as laughter increasingly threatens the Ghost that he starts to be staged not in armor but in some form of 'spirit drapery'." An interesting observation by Jones and Stallybrass is that ...at the historical point at which ghosts themselves become increasingly implausible, at least to an educated elite, to believe in them at all it seems to be necessary to assert their immateriality, their invisibility. The drapery of ghosts must now, indeed, be as spiritual as the ghosts themselves. This is a striking departure both from the ghosts of the Renaissance stage and from the Greek and Roman theatrical ghosts upon which that stage drew. The most prominent feature of Renaissance ghosts is precisely their gross materiality. They appear to us conspicuously clothed. Ghosts figured prominently in traditional British ballads of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly the “Border Ballads” of the turbulent border country between England and Scotland. Ballads of this type include The Unquiet Grave, The Wife of Usher's Well, and Sweet William's Ghost, which feature the recurring theme of returning dead lovers or children.