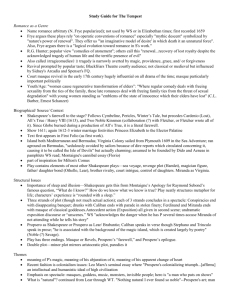

From Female Fairy to Fallen Angel: Interpreting Ariel

advertisement

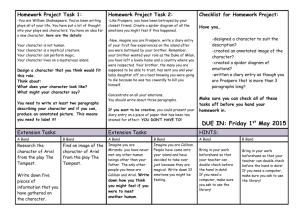

1 From Female Fairy to Fallen Angel: Interpreting Ariel One of the most problematic relationships in Shakespeare’s plays is the one between Prospero and Caliban in The Tempest. A first, superficial reading of the play suggests that Prospero is a wise, dignified, moderately pleasant old man and that Caliban is a heinous villain, but upon closer inspection certain questions arise: Is Prospero really as nice as he seems to be? Is he an entirely reliable narrator? Is Caliban really wicked, or are there redeeming circumstances? Much critical study has been devoted to these two characters, and as a result another fascinating character has had to make do with a place in their shadow: Ariel. Prospero’s other servant may seem a straightforward enough character, but taking a closer look at interpretations and adaptations of his role can evoke interesting questions and yield rewarding results. Ariel on stage The series Shakespeare in Production publishes annotated editions of Shakespeare’s plays which are accompanied by very useful notes and commentary: they focus on the stage productions of the play they are discussing. This series' edition of The Tempest offers a wealth of background information that is not only interesting to read, but also encourages readers to take a closer look at the play. Especially enlightening are the details of how various actors portrayed characters such as Prospero and Caliban, who are open to multiple interpretations, and the seemingly straightforward character Ariel acquires debt when we look at the various stagings. Ariel’s asking for his liberty (act 1, scene 2), for example, has been played with diverse emotions ranging from “wary respect” to “frightening malevolence” (Dymkowski, 245 ff). In this scene, Ariel can be presented as bold and confident, as hesitant, as reasonable and entreating or as sulky and moody, and these various interpretations define his relationship with Prospero and hence comment on Prospero’s character and motives as much as on Ariel's. An Ariel who argues his case reasonably and is rebuked for that will put his servitute to Prospero in a completely different light from an Ariel who has a threatening air or sulks like a moody child. Not only do various interpretations of a character encourage a student of Shakespeare's work to rethink his or her own first impression of that character, but they can also shed light on the importance of cultural circumstances. In her introduction to The Tempest, Christine Dymkowski pays particular attention to the role of Ariel in connection with gender issues; she argues that a director’s decision to have Ariel played by a man or a woman is highly significant for the interpretation of the play. The part in itself is androgynous: although Ariel refers to himself as male (“Ariel and all his quality”, 1.2.193), the roles he plays on Prospero’s orders are all female, namely a sea-nymph, a harpy and the goddess Ceres. It is likely that the part was played at first by a boy-actor, who would of course generally take up the role of a woman.1 The Dryden-Davenant adaption, however, firmly established the part as male and even gave Ariel a female counterpart and lover, Milcha. Dymkowski suggests that a male Ariel ratifies Prospero’s princely power by an act of male subservience. Inherent in this idea is the thought that Prospero’s power could be questioned and hence had to be ratified, and it is precisely this tension which demands that Ariel be played by a woman in later versions where Prospero is a figure of patriarchal authority: “Such a paternalist interpretation of Prospero necessitates a demure Miranda, a beast-like Caliban and an Ariel whose willing servility is seen as natural and inevitable: in other words, a gossamer female fairy” (Dymkowski, 37). From the moment Caliban is staged as a more human figure and Prospero’s 1 Dymkowski follows Keith Sturgess in this, and refers to his work: Jacobean Private Theatre (London: Routledge & Kegan Pual, 1987), p. 77. 2 authority and righteousness is being challenged, Ariel’s bondage is also questioned.2 The spirit is increasingly played by men once more, since a male slave is more disturbing than a woman in a serving role. The subsequent rise of feminism calls for female Ariels who also manage to question Prospero’s authority... and thereby the authority of men over women. A brief look at the history of Ariel’s role in terms of gender shows how culturally defined the interpretation of a play really is: society's view on gender influences the audience's experience of the relationship between two characters (and of course this relationship is inevitably tied to the relationship between Prospero and Caliban). Directors in every generation have their own way of looking at these issues and bringing them across to their audience. An awareness of this helps readers critically examine their own interpretations of The Tempest and exhorts them to understand that no text or an interpretation of that text can exist in a cultural vacuum. Adapting Ariel An interesting adaptation of The Tempest is Tad Williams’s novel Caliban’s Hour. As the title implies, the main character in this work is Caliban, who appears at Miranda’s door and forces her to listen to his version of the story. His narrative is set mainly before the events of The Tempest (though a brief reworking of the play is presented near the end) and presents Caliban as a sympathetic character and Prospero as the villain of the piece. Ariel is for most of the story a brooding presence in the background: Caliban occasionally visits the tree in which the spirit is imprisoned, which is situated in a hidden valley with overtones of the garden of Eden. When he finally is freed (only 40 pages from the end of the novel), Ariel is given the epithet “the Fallen” by Prospero. This, in combination with the characteristic –iel ending of his name (compare Gabriel, Uriel), strongly gives the impression that we are dealing with a fallen angel. This theory is further supported by the fact that Ariel literally fell from the heavens, as Caliban relates: “Then something fell burning from the sky. [...] Something rose from the pit it had dug into the sand, amorphous as smoke, but fast coalescing. My mother fought with it. [... She] at last found the chain of thought that would bind the thing” (Williams, 47). Ariel itself3 claims to be “one of Lucifer’s rebel army”, though at other times it says it is “the shade of a man [Sycorax] had murdered with her witchcraft” (Williams 153). Whatever its origin, in this version of the story there is nothing human or sympathetic about Ariel; on the contrary, it is a willing accomplice of Prospero and delights in cruelly torturing Caliban: As some take their hours of leisure walking or singing, the creature Ariel delighted in following me about, filling my day with tricks and taunts and other persecutions. [...] It flew around my head in the shape of a wasp, stinging me until tears of helpless rage ran down my face. It sang to me songs of my mother’s putrefaction, chirping sweetly of her eyes falling into her skull and her fles becoming sodden muck – even that she and the murdered sow had joined together beneath the earth as a sort of rotting family, that even my dead mother had forgotten me. (Williams, 152) Prospero comes across as a harsh, unfeeling tyrant, but it is Ariel who is pure evil. The spirit is far more malignant and fiendish than Caliban himself in The Tempest ever was. If an author wants to rewrite a story to create understanding and sympathy for a previously maligned character, such as Caliban, he must attempt to explain away this character’s bad deeds (in Caliban’s case, the attempted rape of Miranda and his grumblings against Prospero). In order 2 Dymkowski discusses the influence of colonial thinking and Darwinism on the process of humanising Caliban. In Caliban’s Hour the spirit is neither male nor female and is consistently referred to as ‘it’. Theo D’haen explicitly connects Ariel with Lucifer himself in his analysis of the novel: “The episode in which Caliban and Miranda almost engage in sexual contact uncannily echoes the Biblical scene of Man’s banishment from the Garden of Eden, with Ariel in the rol of the snake” (D’haen, 325). 3 3 to create a sympathetic Caliban, Tad Williams has not only taken the obvious path of turning Prospero into an unpleasant and tyrannical figure, but Ariel is also re-created as a rather nasty piece of work. This effectively turns Caliban into the poor, put-upon underdog who receives nothing but pain for his troubles. Ariel’s role in Caliban’s Hour shows that everything in Shakespeare’s play is interwoven: taking one character (Caliban) and turning him around, immediately necessitates adapting other characters and events to suit this new situation. Such a new reading of the story encourages readers to go back to The Tempest itself and to become more aware of the situation in the ‘original’. By looking at the changes an adapting author has made, for example to particular characters or scenes, readers become more aware of the function of these characters or scenes in the source text. Williams’s reworking of The Tempest gives us a story that fits almost perfectly with the events in Shakespeare’s play, but is seen from another perspective, and thereby encourages us to examine the point of view in The Tempest with a critical eye. It heightens our awareness of the fact that we often only see Prospero’s side of things and it makes us ask questions about his reliability as a narrator; these questions were of course already present in the play itself, but they are made even more visible by this adaptation. In addition, Caliban’s Hour makes us more aware of the complexity of the relationship between Caliban and Ariel. Often, these two are seen as complementing and contrasting each other and are placed in a simple dichotomy, but the rift that is created between them in this novel hints at a more complex situation. They are not simply two sides to one coin and Ariel is not simply a benevolent shadow to Caliban’s fiendishness; he is an interesting, intriguing character in his own right. As is pointed out in Shakespeare’s Caliban, “[a]llegorical interpretations [...] place Caliban in a convenient binary opposition to Ariel. [...] And though at some basic level this opposition is built into The Tempest’s structure [...] it neverheless oversimplifies both Caliban’s and Ariel’s complexity” (Vaughan 82-83). If an adaptation points its readers towards the difficulties and complexity in its source, and thereby helps them to re-examine that source and their own understanding of it, that adaptation can indeed be called succesful. Conclusion Becoming aware of the process of interpretation makes us realise that we ourselves are constantly interpretating: we mean by Shakespeare. An awareness of this makes us more careful and hopefully less prone to pronounce judgment on either original texts or interpretations of those texts. Reworkings of Shakespeare’s work which radically turn around certain aspects of their source or place them in a completely different light, encourage us to reflect upon the role of these aspects within the original play and their place within its structure. In this light, interpretations and adaptations are not only relevant for their own sake, but also help us to examine and understand their source. 4 Bibliography Williams, Tad. Caliban’s Hour. London: Legend Books, 1994. D’haen, Theo. “The Tempest Now and Twenty Years After. Rachel Ingalls’s Mrs Caliban and Tad Williams’s Caliban’s Hour.” Constellation Caliban: Figurations of Character. Amsterdam: Atlanta, 1997. 312-331. Dymkowski, Christine. Introduction. The Tempest. By William Shakespeare. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Ed. Christine Dymkowski. Shakespeare in Production. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. Vaughan, Alden T. and Vifginia Mason Vaughan. Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural History. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.