Civil Rights - Mr. Tyler`s Lessons

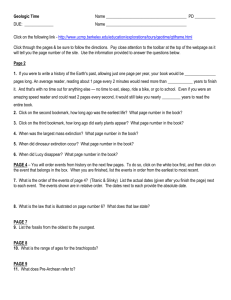

advertisement