An Examination of Virtue Ethics

advertisement

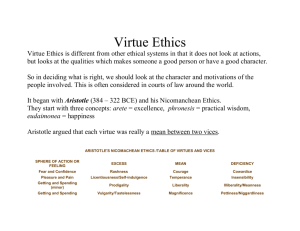

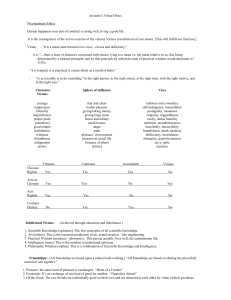

An Examination of Virtue Ethics Brandon Gillette, University of Kansas To the modern1 thinker, questions of morality are phrased almost exclusively as questions of right actions versus wrong actions. This seems to make sense, as all statements about morality are intended to be in some way action-guiding, but to the ancients, medievals, and to some well into the modern period, questions of ethics are properly phrased as questions of good personal character versus bad personal character. Good character traits are referred to as virtues, while bad character traits are referred to as vices. Actions themselves are important, but ultimately are mere instruments for building or revealing character. This writing is a summary of some (but of course not all) of the major ideas of virtue ethics, beginning with the differences between virtue ethics and deontological and utilitarian ethics, continuing on to summarize Aristotle’s account of the virtues, and finishing by identifying some difficulties associated with the virtue ethics approach. One of the places that something like a virtue ethics approach has prospered is in teaching morality to the young. Often parents and teachers will remind children of things like “Nobody likes a sore-loser”, “Cheaters lose in the end”, “Don’t be a tattle-tail” “Patience is a virtue”, or “Don’t be a liar”. The idea is that it is easier, and maybe more effective to identify character traits to encourage or discourage than it is to teach children to consistently apply the hedonic calculus or the categorical imperative. The idea is that by cultivating certain types of personalities, the natural inclinations of these people as adults will conform to our standards of morality. In this way, the virtue ethicist focuses on forming good habits as opposed to adopting a particular kind of decision calculus every time a decision is called for. One motivation for taking a virtue ethics approach seriously is that we tend to only care about whether actions are moral or immoral insofar as they determine how we treat the people that do those actions. In fact, since a person’s character persists through time (unlike a person’s actions, which once done cannot be undone) evaluations of peoples’ characters carry a great deal of weight in interpersonal relationships, and even in legal punishment. Consider the following selection from David Hume: “ The only proper object of hatred or vengeance is a person or creature, endowed with thought and consciousness; and when any criminal or injurious actions excite that passion, it is only by their relation to the person, or connexion with him. Actions are, by their very nature, temporary and perishing; and where they proceed not from some cause in the character and disposition of the person who performed them, they can neither redound to his honour, if good; nor infamy, if evil. The actions themselves may be blameable; they may be contrary to all the rules of morality and religion: but the person is not answerable for them; and as they proceeded from nothing in him that is durable and constant, and leave nothing of that nature behind them, it is impossible he can, upon their account, become the object of punishment or vengeance. According to the principle, therefore, which denies necessity, and consequently causes, a man is as pure and untainted, after having committed the most horrid crime, as at the first moment of his birth, nor is his character anywise concerned in his actions, since they are not derived In philosophy, this means past about 1600 CE, which doesn’t sound modern until you consider that Western philosophy itself is about two and a half thousand years old. 1 © Brandon Gillette 2010 from it, and the wickedness of the one can never be used as a proof of the depravity of the other.”2 Approaches to virtue ethics universally take their inspiration from Aristotle, who not only was the first western thinker to lay out a detailed and comprehensive system of virtue ethics, but the first western thinker to treat ethics as its own subject. At the heart of Aristotle’s approach to ethics is the question of what makes the best kind of life for a person. An argument called the function argument is central to Aristotle’ approach to answering this question. The function argument proceeds essentially as follows: It is clear that the best way to judge whether a builder is good is by the quality of the buildings. Even without someone pointing out what the criteria for good buildings are, we all have a remarkable degree of agreement about what those criteria are (some examples might be sturdiness, comfort, logical design, energy efficiency, etc.). Certain features of a builder, like attention to detail, efficiency, organization, and other features become the virtues of a good builder. In a similar way, to be just a good person (i.e. to live the good life) a different set of criteria for what makes a person or a life good will apply than applied in the specific case of the good builder. The entirety of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (so titled because he wrote it for his son, Nicomachus) concerns examinations of what kind of life is the best and what kind of virtues are central to living the best life for a person. The nuances of Aristotle’s approach to these big questions are too manifold to summarize effectively, but his general method of identifying the virtues is quite straightforward. The method is as follows: For every personal characteristic there exists at least one adjective to describe it. Each of these adjectives describes one of three things, viz. a vice of deficiency, a vice of excess, or a virtue. The virtue is a mean between the vices of excess and the vices of deficiency. One good example is courage or bravery. These words are both favorable evaluative terms when applied to someone. But what of the person who is TOO brave? We have words to describe that such as rash, hasty, impulsive, reckless, foolish. These would be words we would apply to someone who exhibits the vice of excess with respect to bravery. On the other side, words like coward, chicken, wimp, ‘fraidy-cat, etc. describe someone who exhibits the vice of deficiency with regard to bravery. So the courageous person is able to inhabit the mean between the vices of recklessness and cowardice. Each virtue will be discoverable and describable in such terms. One of the interesting consequences of this approach is that the number of virtues is limited only by our vocabulary. This expanding of the virtues makes it difficult to distinguish specifically moral virtues (if there are such things). For example, a virtue of politeness might exist between vices of obsequiousness and rudeness. It is certainly a virtue to be polite, but is it a moral virtue? The answer is unclear. Insofar as politeness contributes to the best life for a person, it is certainly a good, but it feels odd to treat etiquette as part of morality. In any case, most moral philosophers focus on a set of core virtues that typically include something like the following: Prudence: looking after one’s own interests; a mean between selfishness and selflessness Justice: giving to others their due; a mean between giving more and giving less than is due 2 David Hume, “On Liberty and Necessity” An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding © Brandon Gillette 2010 Temperance: pursuing temptation sparingly; a mean between asceticism and selfindulgence Fortitude: facing those things which we are not inclined to face; a mean between weakness and audacity Wisdom: the greatest of the moral virtues, consists in reasoning correctly about the virtues; a mean between ignorance and arrogance. © Brandon Gillette 2010