Word

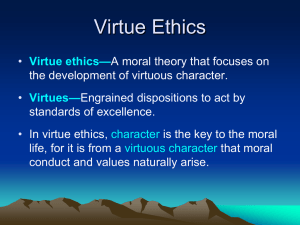

advertisement

Lecture 8 Objectives: After learning this material you will be able to: 1. Present the basic arguments concerning virtue ethics. 2. Understand the Doctrine of the Mean in Aristotle and Confucius. 3. Discuss the nature of the relationship between feeling and virtue. 4. Understand the issues concerned with feminist care ethics. 5. Reflect on the principles of moral integrity and the unity of virtue. 6. Compare and contrast the relationship of virtue to different ideas concerning moral education. Welcome back! The last lecture continued to explore some of the ideas that imply that morality and ethics are based on universal principles. Specifically we studied deontology (the ethics of duty) and rights ethics to help us understand how these theories influence our understanding of what is good. In this lecture we will present a final ethical theory called virtue ethics. The emphasis here is on becoming a good person rather than on following specific moral guidelines. How we become virtuous depends partially on how you answer the question of whether we are born good, evil or neutral. In the process we will seek to understand whether virtue itself is relative or universal. Virtue Ethics and Character There are people who do good things without being able to give a so-called “reason” for doing so. They may never have studied ethics and might not know the difference between duty ethics and utilitarianism. Yet they do good and desire to do good. This is because goodness springs from who they are rather than what they believe or think. “Virtue ethics emphasizes right being over right action. The sort of person we are constitutes the heart of our moral life. More important than the rules or principles we follow is our character. A person of virtuous character can be depended upon to do the right thing. Virtue ethics, however, is not an alternative to ethical theories that stress right conduct, such as utilitarianism and deontological theories. Rather, virtue ethics and theories of right action complement each other” (Judith A. Boss, Ethics For Life: A Text With Readings, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2008] p. 400. Hereafter referred to as Boss.) Some people think that all of the effort we put into trying to figure out what is right is a waste of time. If we would focus our energy on simply becoming a person of virtuous character then we would not need to worry about what is best; we would simply act in the best way possible for all concerned. In reality it might not be all that simple. People of good character do not always agree on what is best and sometimes must struggle with uncertainty, but it is still an important part of the equation. If we both develop our character and learn the rules we have covered so far in this course then we have a much better chance of living authentic lives of goodness and being able to live without regrets. What is a Virtue? 1 We hear a lot during political campaigns about the “character issue.” We want our leaders to be people of character and by that we usually mean virtuous people. But what is virtue? “A moral virtue is an admirable character trait or disposition to habitually act in a manner that benefits oneself and others. We often speak of virtue in terms of individual traits, yet virtue is more correctly defined as an overarching quality of goodness or excellence that gives unity and integrity to a person’s character. A vice, in contrast, is a character trait or disposition to act in a manner that harms oneself and others. Vices stand in our way of achieving happiness and the good life” (Boss, p. 401.) Rather than a static quality, a virtue such as courage is a dynamic quality because it is always changing and adapting itself to situations. It is also important to see how the virtues are not an abstract idea, but a helpful quality that makes our lives better. The virtues help us live in a way that brings happiness and honor rather than sadness and shame. We misunderstand virtue when we think of it as only about goodness and character rather than about joy and fulfillment. “Virtue ethics is based upon certain assumptions about human nature. Most virtue ethicists believe that virtue is important for achieving not only moral well-being but also happiness and inner harmony. Aristotle referred to this sense of psychological well-being as eudaemonia. Eudaemonia is not the same as what utilitarians or egoists mean by happiness. Rather, it is a condition of the soul or psyche; it is the good that humans seek by nature and that arises from the fulfillment of our function as humans. Eudaemonia is similar to Eastern and modern Western concepts such as enlightenment, nirvana, self-actualization, and proper self-esteem” (Boss, p. 401.) The Buddha taught people how to end their suffering. There are many aspects to this, but one important component to his solution (known as the Noble Eightfold Path) is to live in such a way that we do not create more misery for ourselves and other people. This is only possible when we live in an ethical manner, one that is fostered by living a life of virtue. The Role of Intention During this course we have discussed the outcome of our actions (utilitarianism) and doing our duty (deontology), but you may have noticed that we have not spent much time discussing what role our intentions play. This is the realm of virtue ethics. “An action may be morally good because it has a certain quality, such as being beneficial; however, this in itself does not make it a virtuous act. For example, a wealthy person may give a million dollars to a charity simply because she wants the tax deduction or a building named after her. Although the act itself is good in terms of its consequences, we would probably hesitate to say that she is virtuous for doing it. The actions of a virtuous person stem from an underlying disposition of concern for the well-being of others and themselves, or what Aristotle called ‘a certain frame of mind.’ A poor widow may give her last coin to the needy out of compassion. Although the consequences of her action 2 are not nearly as far-reaching as those of the wealthy patroness, most people would agree that the widow is the more virtuous of the two” (Boss, p. 404.) This is a good example of how a virtuous person is something much deeper than simply the sum total of their actions. This is because a virtuous person includes qualities such as motivation. A person who does good only to be noticed or to get something in return is missing an important part of what it means to be a good person, a person of character. In the same way, a person of character can do something wrong or make a mistake and we feel differently about this from a person who does not mean well and makes the same error. On one level an error is an error; what difference does it make? Yet we realize it makes all the difference in the world. Sometimes people avoid confrontations by not taking a stand on an issue. Often this does not matter and may even be wise! But other times not taking a stand is actually making an important choice in terms of ethics. If you see someone being hurt and you do not do anything to stop it, what does that say about your character? “Simply refraining from harming others is not enough to make us morally good people. It is also necessary to cultivate a good will. Performing morally good actions strengthens a virtuous disposition. Action and practice are the means by which our natural predisposition and energies are developed into virtues. According to Mill, reflection, which includes moral analysis, provides the bridge that connects action and the cultivation of a virtuous disposition. Our actions test our old habits and call upon us to reflect on our past actions and to reevaluate ourselves and our alternatives. Reflection, which is grounded in moral values, in turn generates a habitual virtuous moral response” (Boss, p. 405.) This is one of the reasons why Socrates taught that the unexamined life was not worth living. Self-Knowledge Socrates knew that people who avoided learning about themselves would only end up unhappy. Now we know from modern psychology why he was right. The unconscious has a huge influence on our motivations and behavior and if we want to live lives of goodness and character then we need to become more conscious. For example, if we don’t face our anger we may avoid hitting someone if we are strong on self-discipline, but we only push the anger down into the unconscious where it remains a volatile energy. Eventually it reemerges as passive-aggressive behavior that even we ourselves do not understand unless we are able to learn to work with this repressed energy. A person of character works to become more conscious. This work on consciousness is also a work of developing virtue because it forms what psychologists call a positive feedback loop. The more conscious we become the less we hurt others. The less we hurt others the less shame we feel and thus we are more willing to explore our depths (rather than hide) and 3 uncover our unconscious motivations. This is why the Buddha taught his disciples to both meditate and live an ethical life. Meditation would help them ethically and living ethically would help their meditation. We see a similar understanding of what today we would call psychology in Greek philosophy. “According to Aristotle, immorality results from a disordered psyche. Virtue serves as a correction to our passions by helping us resist our impulses and passions that interfere with us living the life of reason: the good life. For example, the virtue of courage is a corrective to the emotion of fear. Temperance is a corrective to the temptation to overindulge or to seek immediate pleasure. Aristotle, however, did not want to see passion eliminated; he recognized that emotion is an important component of moral goodness. Although our emotions and passions should always be subject to the control of reason, this is not the same as saying that emotions are bad and should be eliminated. Rather, he was saying that emotions such as fear or boldness and anger or pity are appropriate at times, but only when they are under the control of reason” (Boss, pp. 408409.) Our passions are also what enable us to will the good according to philosophers such as David Hume and feminist care ethics. It is one thing to know the good and another thing to do what is right. One of the main sources of motivation we have is our feeling, which needs to be engaged rather than suppressed. Unfortunately, for various historical reasons, the life of virtue became associated with a life of denying the feelings. The wisdom of coming to know ourselves and of bringing our feelings into our lives (guided by reason of course) is found in both the East as well as the West. “There are strong strands of virtue ethics in both Buddhist and Hindu ethics. Both stress the importance of reason and wisdom in the virtuous life. Buddhist virtue ethics is also teleological in that it is directed toward the end of self-realization or Nirvana or the extinction of suffering. According to Buddha, the normal human condition is accompanied by suffering. In addition to ignorance and irrationality, two major causes of suffering are the moral vices of greed and hatred. To overcome suffering, we need to cultivate wisdom as well as the virtues of giving and love” (Boss, p. 409.) For the Greeks, especially Aristotle, the greatest virtue was wisdom because without this virtue we would not be able to put the others to their best use. Religious people sometimes place faith and/or love above wisdom, but it will nevertheless be high on their lists as well. The goal of a virtuous life is to live with both an open heart and an open mind. Love and wisdom are the keys to understanding virtuous people. Aristotle and Confucius: The Doctrine of the Mean You have probably heard of the virtue of moderation. A famous proverb says: “All things in moderation.” The Buddha taught the “middle way” between the 4 extremes of asceticism and self-indulgence. It is no surprise then that virtue ethics also looks to a middle way of its own. “The Doctrine of the Mean is found in both Eastern and Western philosophies. According to the Doctrine of the Mean, most virtues entail finding the mean between excess and deficiency. Some character traits or dispositions, however, are good or evil in themselves. For example, both Confucius and Aristotle believed that ignorance and malice are always vices, and wisdom is always a virtue. In Buddhist ethics, the virtue of ahimsa, or nonharming, which is reflected in a person’s respect for all living beings, is good in itself. For Confucians, ‘absolute sincerity’ is always a virtue and is considered the highest virtue that we can cultivate. ‘Only those who are absolutely sincere,’ Confucius wrote, ‘can fully develop their nature’” (Boss, pp. 411-412.) In other words, moderation in most things is important but that does not mean you have to be moderate in the amount of wisdom and love you have or that you can be moderately cruel. We have to be careful to not take the idea of moderation out of its context. Part of this context is to not use the idea of moderation to justify a lack of involvement in important issues. “The doctrine of the mean should not be misinterpreted as advising us to be wishy-washy or to compromise our moral standards. Aristotle and Confucius were not suggesting that we seek a consensus or take a moderate position. The doctrine of the mean is meant to apply to virtues, not to our positions on moral issues. Aristotle was not referring to being lukewarm or a fence-straddler but to seeking what is reasonable” (Boss, p. 412.) Aristotle taught people to analyze extremes such as cowardice and foolhardiness to find the mean, which is the virtue (in this case courage.) It is too easy for young men to do foolhardy things and call it courage, but courage as a virtue will not contradict another virtue such as being able to use our heads. Courage does not require us to be stupid! Finding virtue, however, is not as easy as looking something up in a chart. This is, once again, because of its dynamic nature. “How do we know when we have found the mean? The mean in this context is also not the same as the mathematical mean. There are no formulas or rules for deciding what is virtuous for a particular person in a particular situation. Aristotle offers the following practical advice: ‘(1) Keep away from that extreme which is more opposed to the mean…(2) Note the errors into which we personally are most liable to fall…(3) Always be particularly on your guard against pleasure and pleasant things.’ By living according to the doctrine of the mean, Aristotle and Confucius both believed, we can find the greatest happiness and inner harmony. To do this, it is important to be aware of the tendencies of your personality so that, if necessary, you can habituate yourself to compensate for them. This involves noticing how you respond to others and listening to your conscience” (Boss, p. 414.) In other words, to live a life of virtue we have to live a life of mindfulness. To live mindfully we must work to increase our awareness and consciousness so that we do not slip into evasions and rationalizations and all of the other fallacies we studied earlier in this course. 5 David Hume: Sentiment and Virtue While Aristotle thought wisdom was the most important virtue and reason its greatest tool, not everyone agrees with him. “Most Western philosophers emphasize reason over sentiment; others, such as David Hume (1711-1776) and Nel Noddings (b. 1929), believe that sympathy and caring are the most important virtues. According to these philosophers, moral sentiments like compassion and sympathy are forms of knowledge regarding moral standards that should be taken seriously. Sympathy forms the heart of our conscience and complements rather than competes with the more cognitive virtues. Sympathy involves both feeling pleased by another’s accomplishments and feeling indignation at another’s injury or misfortune. Sympathy joins us to others, breaking down barriers. In Confucian ethics, caring and loyalty in the context of the traditional family are extremely important. It is absurd, Mencius argued, to claim that one ought to save a stranger rather than one’s child; our special obligations to those we have a relationship with goes beyond our abstract obligations to one another as humans” (Boss, p. 415.) We can verify this idea in what we give our time and money to when it comes to good causes. For example, there are a multitude of wonderful charities. So why do we give to one and not another? It is not a purely rational decision because on rational grounds any honorable charity can be supported. The difference seems to be in our feelings. We are moved not simply by an idea, but by a feeling. This is why feelings can be considered as a form of knowledge, a way of knowing. Hume made this same point because it seemed to him that many great philosophers had missed this point. “Unlike Kant and Aristotle, Hume argued that reason or reflection can only tell us what is right or wrong. Reason, however, cannot move us to act virtuously. Instead, it is sentiment that actually moves us to act virtuously. According to Hume, sympathy is the greatest virtue, and cruelty, or the lack of sympathy, is the greatest vice. His claim is not without empirical support. In a study of people who rescued Jews during World War II, most rescuers reported that they rarely engaged in reflection before acting. They reported that they acted instead from a sense of care and sympathy” (Boss, p. 416.) We often don’t even have time to reflect on what we “should” do; instead we do what comes naturally to us. This is why the formation of our character is so important. One of the things developmental psychologists look for in people as they mature is a growing circle of care and sympathy. Someone who only thinks of himself or herself is fine as a baby, but as an adult it is very sad because they are virtually disabled. The virtues help us expand our understanding of who and what is included in our moral circle. “Sympathy opens us up to others by breaking down the us/them mentality that acts as a barrier to expanding our moral community. Sympathy involves being in relationship in a way that reason does not. The 6 sympathetic person sees service as a mutual process where all parties are engaged. Sympathy as a virtue entails listening to the people we are serving rather than defining their problems ourselves and imposing our ready-made solutions. Sympathy opens up our hearts to bear the stories of those we are serving. By allowing them also to serve us, we can learn from their experiences and their strengths” (Boss, p. 417.) This is one of the great values of doing community service work. We do it to be of service, but in the process we usually gain so much more because our hearts expand and we grow more kind. It is all too easy for ethical theories to simply become divorced from life and loss in the realm of abstractions. “Justice and reason demand that everyone be treated equally, but caring requires also that our moral decisions be made in the context of relationships” (Boss, p. 418.) Theories do not mean a whole lot until we face real suffering and misery and then seek to solve the problems we face. Then ethics becomes practical as we seek the good in the concrete world of real life and real people. It is so easy to say the poor should take care of themselves from the place of theory. But when one is confronted with real poverty then one aches to help alleviate such deprivation. Feminist Approaches to Ethics The voice of women has been absent for too long due to the patriarchal culture that informed so much of our world’s values until recently. But this is changing and women philosophers are beginning to be heard not only in academia, but also in politics where ethics comes alive and gets applied (or ignored) on a large scale. “Western ethical theory has been faulted by feminists as showing little concern for women’s rights and interests, and for valuing traditional masculine traits and virtues such as reason, independence, individual achievement, and autonomy over traditional feminine virtues such as sympathy, interdependence, community, and peace. Most modern feminist ethicists, such as Carol Gilligan, believe that these gender differences are a combination of nature and nurture. In addition, feminist ethicists maintain that the issues that arise in the ‘private world’ of home and family have been too often dismissed by traditional ethicists as boring and morally uninteresting” (Boss, p. 419.) What would it be like to have a gender-equal ethics? It would mean a new understanding of balance, where men’s and women’s values combined in new ways to create a new ethics. It will be exciting to see where it all goes. One of the main complaints of feminist care ethicists is that traditional masculine ethics are too abstract. “While care ethicists do not reject the use of principles altogether, they believe that it is care, not rational calculations or an abstract sense of duty, that creates moral obligation. In other words, practical morality is constructed through interaction with others, not merely by an autonomous examination of the dictates of reason” (Boss, p. 419.) We learn more from acting ethically and practicing virtue than from reading about it. We might understand the importance of kindness intellectually, but then one day when we are down 7 someone really does something kind for us and it “blows us away.” We will always have a new understanding of what it means to be kind because it has become real to us. We can see how this new level of kindness comes into play when it comes to how we treat animals. There are all sorts of arguments out there that inform of us on different sides of whether or not we should eat animals, experiment on them and other such ethical subjects. But what touches our feelings? “Ecofeminist Karen Warren expands care ethics to include all living creatures and all of nature. Care, according to her, is unlimited by the ability of the recipient to reciprocate. She argues that the virtue of sympathy of care joins us to others and breaks down barriers, not just between humans, but between humans and the rest of the natural world. Like many of the early feminists, she maintains that one of the goals of feminism is the liberation of nature as well as women by erasing oppressive categories based on superiority and privilege, and ‘the creation of a world in which difference does not breed domination.’ To do this, Warren argues, we need to cultivate what philosopher Marilyn Frye refers to as the ‘loving eye’ of care ethics rather than the ‘arrogant eye’ of an ethics based on domination and conquests” (Boss, p. 424.) Usually the best way to change someone into a vegetarian (or at least a more conscious consumer of organic meats) is not to argue with him or her but to show him or her the way most animals are treated in the process of becoming items on the table. Then something besides the intellect is engaged, feelings are touched, and behavior changes. It is a very interesting process! Is Virtue Culturally Relative? We have been studying virtue and now it is time to address the issue of relativism once again. Are virtues constant and universal? “Although different cultures and groups of people may emphasize different virtues (sociological relativism), this does not mean that virtue is culturally relative in the sense that the concept of virtue is a cultural creation. Indeed, what is most striking are the similarities among the various lists of virtues rather than the differences. For example, anthropologist Clyde Kluckholn noted that, among the Navaho, the primary virtues are generosity, loyalty, self-control, peacefulness, amity, courteousness, and honesty. These virtues are not seen as peculiar to Navaho but are regarded by them as desirable for all humans and as universal as the air we breathe” (Boss, p. 428.) Let’s look at another culture. “The Egyptian text The Instruction of Ptahhotep, written more than four thousand years ago, states that the following virtues should be practiced toward everyone: self-control, moderation, kindness, generosity, justice, and truthfulness, and discretion. The Swahili proverbs teach that a virtuous person is kind, cautious (prudent), patient, courageous, selfcontrolled, humble (in the Kantian sense), honest, fair, responsible, respectful, and cooperative. Thus, although the relative importance of different virtues may 8 vary from culture to culture, the list of what are considered virtues and what are considered vices seems to be transcultural” (Boss, p. 428.) Just as we can say all people need to eat food but different people eat different kinds of food, so all people need the virtues even though how the virtues are rated differ from one culture and time to another. For example, I mentioned earlier how the Greeks valued wisdom above all of the virtues, while Christians value love as the greatest virtue. Nevertheless, both the Greeks and Christians value love and wisdom, only the emphasis placed on each differs. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) questioned the virtues of traditional Christianity, but he did not question virtue itself. In fact he proposed his own greatest virtue, known as the will to power, which has been greatly misunderstood and abused. “By the will to power, Nietzsche meant ‘the will to grow, spread, seize, become predominant’ that is found in all living beings. The will to power involves the experience of living at its greatest. In his book, The Dawn, Nietzsche lists ‘The good four. Honest with ourselves and whatever is friend to us; courageous toward the enemy; generous toward the vanquished; polite - always; that is how the four cardinal virtues want us.’ Weak people, in contrast, make humility, selfsacrifice, and equality into virtues because they lack the courage, power, and personal resolve to live the life of the great person. Thus, the Christian ‘herd morality’ drags the best and strongest people down to the lowest common denominator” (Boss, p. 430.) Nietzsche questioned values such as humility and forgiveness if they were used to allow people to continue to abuse us or for people to put up with evil governments. Karl Marx complained that religion was the opiate of the people for the same reason. While there are other ways to understand these religious virtues of course, the fact is that Nietzsche and Marx were dealing with the facts around them, not with the theory of what these virtues could mean. Nietzsche taught that some characteristics that were called virtues were actually ruining society. “Like junk food that is bad for our bodies, virtues that impede our growth as humans are junk virtues. A culture that promotes junk virtues as true virtues is destructive to the development of moral character” (Boss, p. 430.) One example of a modern American “virtue” is the push to be busy and efficient. While there is nothing wrong with these traits in themselves we can also see how they can lead to the feeling that there is never enough time and we are always rushing around trying to take care of millions of things. Many Americans have lost a sense of the values of silence and contemplation. Our growing level of anxiety and depression may very well speak to this issue as well. One of the things that most philosophers, East and West, ancient and modern, seem to agree upon is that virtue is not a simple given, but that it must be cultivated. “A virtuous character does not develop in isolation but in community. As Aristotle pointed out, we do not become more virtuous by merely reflecting on or intellectualizing virtues but by living a virtuous life. A good society provides an 9 environment where virtues are encouraged and where people can thrive and develop to their fullest potential” (Boss, p. 431.) An interesting task is to analyze different cultures according to how well they advocate and support the virtuous life. Take a look at modern popular culture in the United States and ask yourself what it leads to and what it celebrates. It is not always a pretty picture! This is why we are very fortunate if we have virtuous people in our lives. Their presence in our lives is the best guide to whether or not we can live virtuous lives ourselves. Moral Integrity and the Unity of Virtue If we are not careful it is easy to talk about the virtuous life as if it is only a collection of separated characteristics that you either possess or do not. But it is more than that. When we look closely at what is going on we see that the sum is greater than its parts. “According to Aristotle, virtue is a unifying concept rather than simply a collection of different personality traits. We speak of a good person as being virtuous in a general sense. Virtue, in other words, is the disposition that predisposes us to act in a manner that benefits ourselves and others” (Boss, p. 432.) That is why we see virtuous people as loving and wise and kind… Different characteristics may manifest under different conditions and requirements, but what we really intuit is a general sense of goodness. This is what makes virtuous people so attractive. To a certain extent humans are a contradictory species! We are both lazy and ambitious, loving and spiteful, forgiving and judgmental. But one of the things we find attractive about virtuous people is how their character seems to come together into a seamless whole. “The concept of virtue as a unifying principle in the human psyche, rather than a collection of discrete personality traits, is found in both Eastern and Western virtue ethics. Nietzsche regarded the will to power as the fount of all virtuous action. In Chinese philosophy, hsin - that which is one with nature and the principle of all conscious and moral activity - is the source of all virtue. Virtue, according to Confucian ethics, stems from an all-pervading unity” (Boss, p. 432.) Once again we have a positive feedback loop where the virtues lead to unity and unity supports being able to live a virtuous life and be a fulfilled person. Unity within our nature leads to greater contentment and less suffering. We don’t experience as much tension and fear because we can relax more into the present moment. “The good life entails cultivating all the virtues, it involves living a life of integrity. Without integrity, we are not truly virtuous because there is still disharmony within ourselves” (Boss, p. 433.) One of the ironies of life is that when we feel restless and discontent we look for something in the outer world to bring us peace or at least distraction. But the real answer, we are told by so many sages, is to find peace within. One way to do find this inner peace is to become a unified person, a virtuous human being. 10 But lest we become discouraged early on we must begin the journey with an emphasis on each step rather than on our future destination. “The cultivation of virtue and the good will is a lifelong process. Very few people ever attain a level of moral development where they no longer struggle against temptation. According to Aristotle, for those who constantly strive to be virtuous, being a virtuous person gradually becomes much easier and more pleasurable. To determine whether we are virtuous people, Aristotle suggests that all we must do is ask ourselves whether we find pleasure in acting virtuously” (Boss, p. 434.) When it seems difficult to do the right thing we know we still have to mature and grow up into more loving people. When we find it actually brings us both peace and energy to do what is right then we know we have started down the right path. Sages often give up many things valued by popular culture such as wealth and loose living. But they say popular culture has really given up the most because people who live according to the standards of a materialistic culture have given up in so many cases peace, joy, and fulfillment. Which people, they challenge us, have given up the most? Virtue and Moral Education We have discussed the need to cultivate the virtues, but we have not yet brought in an underlying problem. It seems that how we go about cultivating a virtuous life depends to a certain extent on how we see ourselves in the first place. Are we naturally bad? Good? Neutral? “Lao Tzu regarded people as basically good. The Tao, he maintained, not only shapes our character but provides us with ethical principles. We have only to lose ourselves in the Tao just as a fish loses itself in water. Cultivating virtue involves letting go and letting the guiding principles flow naturally out of the Tao. However, Lao Tzu did not advocate apathy and shutting ourselves off from the world. Moral education instead involves being open to others and affirming their natural goodness” (Boss, p. 435.) Thomas Aquinas, a medieval theologian, thought that people were born with a sinful nature, but through a combination of grace and grit people could lead the virtuous life. Because people naturally leaned toward what was wrong, they had to undergo a deep inner transformation and then combine this with a vigorous discipline to educate their character. The Greeks seemed to come down somewhere in the middle between Christianity and Taoism. “For Aristotle, it is not enough to simply nurture our natural inclinations. The cultivation of virtues requires willpower and practice as well. We acquire virtue primarily through repetition or habituation. Because humans are social as well as rational beings, becoming virtuous involves both the cultivation of reason and proper socialization. We do not become just simply by believing in the principle of justice. We become just or unjust in the course of our dealings with others. It is our duty, therefore, to practice the various virtues so that we will become proficient” (Boss, p. 435.) While Aristotle placed a great deal of emphasis on our actions, the Buddha would place even greater emphasis on our thoughts. He taught that we needed to change our thinking, and once we 11 did that we would see our actions begin to fall into place more naturally and gracefully. This is one of the reasons why Buddhism has so much emphasis on meditation and on learning to see the world correctly according their philosophy. When we see things through eyes that have not been trained, we see a superficial world, which then leads to a superficial life. Critique of Virtue Ethics The biggest problem with virtue ethics is the same problem we have seen with each of the rules we have studied in past lectures. It is great as a piece of the puzzle, but it does not work well if it is seen as complete in itself. “The primary criticism of virtue ethics is that it is incomplete. Virtue ethics has been criticized for its lack of emphasis on actions” (Boss, p. 437.) Some people feel that if you just talk about being a good person you forget that good people must do good things! But usually this is not such a problem. It would seem that it is easier for “bad” people to do good things for some ulterior reason then for a good person to avoid doing what is necessary. This is because the nature of goodness seems to be to give itself away in compassion and service. Is being a virtuous person enough? Most philosophers do not think so. “Virtue alone does not offer sufficient guidance for making moral decisions in the real world. Virtue may be adequate for the saint, but most of us also need formal moral guidelines” (Boss, pp. 437-438.) If we are a virtuous person we might lean more naturally to do the good, but that does not always make the good clear, especially in our increasingly complex world. Most good people still struggle with the great moral questions. This is why even virtuous people benefit from understanding moral theory and studying moral rules as we have been doing in this class. It used to be that the only real care the poor and sick received came from charitable organizations, both religious and secular. But what happens when the state takes over many of these functions? “Virtue ethics goes beyond pure duty and rights-based ethics by challenging us to rise above ordinary moral demands. Philosopher Christina Sommers argues that individuals are transferring too much responsibility for the well-being of others onto institutions and professionals. She concludes that these solutions are incomplete and that what is needed instead is the virtuous individual” (Boss, p. 438.) It is important to send off a check to different groups doing good works, but virtue ethics tells us that it is necessary for us to get more actively involved as well because it is only in the practice of virtue in relationship with other people that we truly become good. The best thing about virtue ethics is that it challenges us on the level of our motivations and intentions. This seems to have been the interest of Jesus as well. When he taught people that not only should people not commit adultery, they shouldn’t even look upon one another in this way, he was moving morality inward. It is not enough to just follow the rules. “The development of a virtuous 12 character is essential to the concept of the good life and the good society. While virtue ethics does not stand on its own as an independent moral theory, nor do most virtue ethics intend to, virtue ethics offers an important corrective to a morality based on abstract moral principles and rights” (Boss, p. 439.) When we bring all of the various rules we have studied together with an emphasis on becoming a good person, a person of character, we begin to approach the ideal of being able to apply moral theory in real life. Reflection: Applying Moral Theory in Real Life I hope that one of the things you have learned in this class is to question the value of moral relativism and subjectivity. There is a certain place for sociological relativism, but it is a fallacy to jump from that to ethical relativism. “As people mature in their moral reasoning, they look to universal moral principles and sentiments, rather than relativist theories, for moral guidance. According to developmental psychologists, people at the higher stages of moral reasoning tend to make more satisfactory moral decisions and are better at resolving moral dilemmas” (Boss, p. 441.) Mature people are able to accept and celebrate differences and diversity without condoning injustice in the name of respect and tolerance. Let’s briefly review what we have learned so that we can tie it all together. “Utilitarianism, one of the first universal moral theories we studied, has proven to be very useful in evaluating and developing public policy. However, it risks neglecting personal integrity in seeking the greatest good for the community. Ethical egoism, on the other hand, focuses too much on the individual to the neglect of the community and social good” (Boss, p. 441.) Once again, we see how these two opposite ideas contradict one another when standing alone, but how both can bring important ideas that should be included in any integral ethical theory. If we can’t simply judge the goodness of an act by its consequences then we might be tempted to judge it only by the nature of the action itself. “Kantian deontology, while offering a strong foundation for ethics in the form of the categorical imperative, tends to be too demanding. It also ignores consequences in making moral decisions. Prima facie deontology provides a corrective to the rigidity of Kantian deontology and, at the same time, recognizes future-looking duties. However, neither form of deontology adequately addresses the issue of moral rights. Rights ethics, on the other hand, without being tied to deontology, allows the strong to assert their rights at the expense of the weak” (Boss, pp. 441-442.) It is easy to get so caught up in the rules that we ignore the consequences. This can be a disaster. When it comes to rights ethics, and we grow up in a democracy we tend to think that the majority is right. But history gives us example after example of where the majority has failed to see what is good. Thus there has always been fear of the 13 “tyranny of the majority.” “Finally, virtue ethics points out the importance of a virtuous character in morality and the importance of seeking the mean. However, it does not, on its own provide adequate guidelines for making moral decisions in everyday life, especially ones involving issues of justice” (Boss, p. 442.) An emphasis on intention and underlying motivations brings balance to the many ethical theories that focus on the outward actions rather than the inward development of people and how these traits contribute to the moral life of a society. What happens when we bring them all together? “While all the moral theories we studied have a different focus, there is a great deal of overlap between the universal moral theories. They all claim that moral principles should be applied universally and impartially. They all require that we treat persons with respect whether person be defined as all sentient beings or, more narrowly, as only rational beings. All the universal moral theories promote self-improvement in virtue and wisdom” (Boss, p. 442.) It is frustrating to see how people can be so narrow in their outlook that they make their theory of life, their way of seeing the world, the only way. So often this fundamentalist approach - “My way or the highway” - can lead to the very evil it was trying to avoid in the first place. Thus it seems that one important hint we are learning about morality is that it is more conducive to growth and maturity to include more rather than less. One of the things I hope you have learned to appreciate throughout this course and in your own wrestling with ethical issues is that ethical decisions are not as easy as many would have us think. “W.D. Ross likened moral decision making to the artistic process. According to Ross, there is no set formula for determining which action we should take in a moral dilemma. The general duties themselves may be self-evident, but judgments about our duties in a particular case are not. Instead, we need to use reason and creativity to make judgments about our duty in that situation. Ross believed that this lack of clarity is due to the nature of moral decision making, which, he claimed, is more like creating a work of art than solving a mathematical problem. The finished paintings might look very different, but we are all painting from the same palette. Universal moral principles, like the artist’s palette, provide the form rather than the specific content of our final decision. Ross believed that, to demand ethicists provide us with predetermined moral decisions is as unreasonable as artists demanding that their mentors tell them exactly how their finished works should look” (Boss, p. 443.) We must not let the lack of absolute certainty lead us to think that everything is purely subjective. The great moral leaders of our world have far more in common than not. Thoughtful people may not always do the right thing, but they are not nearly the danger to civilized society as are people who do not bother to think and reflect much at all. Thoughtful people make use of the wisdom that has been handed down to us. “Like any creative undertaking, moral decision making requires the proper tools and expertise in reasoning, but it also demands that we personally enter into the 14 process. The sort of moral decisions we make says as much about the kind of people we are as it does about the universal moral principles themselves. Thus, in making satisfactory and well-informed moral decisions in your life, it is important to know yourself and to constantly strive to overcome immature defense mechanisms and narrow-mindedness and to become a more virtuous and wise person” (Boss, p. 443.) The wonderful thing here is that as we undertake the journey to lead a life of goodness we can see the fruits of such an endeavor in our own level of growing serenity and peace. Summary We will conclude this class in the next lecture by returning to where we began, the world of philosophy and questions. When people ask me how I can teach ethics, I always tell them I can’t, really. All I can do is try to get people to think and be self-reflective. Thankfully this alone seems to be enough. Just as we cannot make plants grow, we can provide them with optimal conditions for growth to naturally occur when the plant is ready to follow its own inner nature to expand. It seems to me that ethical and philosophical education is very much the same. If plants need water and sunshine then I think students need Ken Wilber and Jacob Needleman. In the last lecture I want to introduce you to the new field of Integral Philosophy and how it can enhance our ability to exclude less and include more. I will close the last lecture by having you study again the importance of questions in philosophy and the Socratic method in particular to help us all think more deeply about life and become more contemplative people. In the process we will see the importance of dialogue, questioning, and selfknowledge in allowing philosophy to become not simply a subject studied, but a way of life. Until then, celebrate the virtuous life! Bibliography: Judith A. Boss, Ethics For Life: A Text With Readings, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2008] Donald Palmer, Looking at Philosophy: The Unbearable Heaviness of Philosophy Made Lighter, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2006] Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, [New York, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945] Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View, [New York, New York: Harmony Books, 1991] 15 Bruce Waller, You Decide! Current Debates in Contemporary Moral Problems, [New York, New York: Pearson, 2006] 16