Death of the Moth.doc - English

advertisement

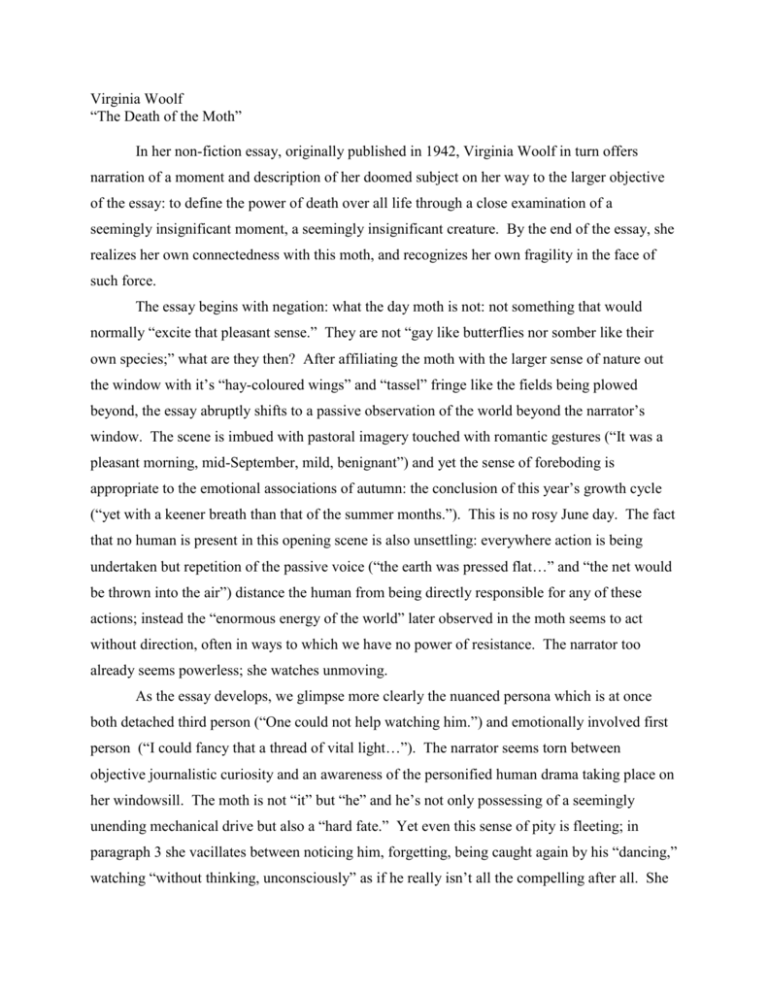

Virginia Woolf “The Death of the Moth” In her non-fiction essay, originally published in 1942, Virginia Woolf in turn offers narration of a moment and description of her doomed subject on her way to the larger objective of the essay: to define the power of death over all life through a close examination of a seemingly insignificant moment, a seemingly insignificant creature. By the end of the essay, she realizes her own connectedness with this moth, and recognizes her own fragility in the face of such force. The essay begins with negation: what the day moth is not: not something that would normally “excite that pleasant sense.” They are not “gay like butterflies nor somber like their own species;” what are they then? After affiliating the moth with the larger sense of nature out the window with it’s “hay-coloured wings” and “tassel” fringe like the fields being plowed beyond, the essay abruptly shifts to a passive observation of the world beyond the narrator’s window. The scene is imbued with pastoral imagery touched with romantic gestures (“It was a pleasant morning, mid-September, mild, benignant”) and yet the sense of foreboding is appropriate to the emotional associations of autumn: the conclusion of this year’s growth cycle (“yet with a keener breath than that of the summer months.”). This is no rosy June day. The fact that no human is present in this opening scene is also unsettling: everywhere action is being undertaken but repetition of the passive voice (“the earth was pressed flat…” and “the net would be thrown into the air”) distance the human from being directly responsible for any of these actions; instead the “enormous energy of the world” later observed in the moth seems to act without direction, often in ways to which we have no power of resistance. The narrator too already seems powerless; she watches unmoving. As the essay develops, we glimpse more clearly the nuanced persona which is at once both detached third person (“One could not help watching him.”) and emotionally involved first person (“I could fancy that a thread of vital light…”). The narrator seems torn between objective journalistic curiosity and an awareness of the personified human drama taking place on her windowsill. The moth is not “it” but “he” and he’s not only possessing of a seemingly unending mechanical drive but also a “hard fate.” Yet even this sense of pity is fleeting; in paragraph 3 she vacillates between noticing him, forgetting, being caught again by his “dancing,” watching “without thinking, unconsciously” as if he really isn’t all the compelling after all. She bestows attention upon him unwontedly. The observer is torn between extending efforts to assist this hard working creature, one she feels intimately connected with: he represents a “simple form of the energy that was rolling in at the open window..in my own brain and in those of other human beings” but in the end she chooses not to. Why? Because it all seems so futile. His efforts are futile, hers would be futile, the whole world’s efforts to deny the ferocity of the power of death would all be inevitably wasted. So why bother. The narrator ends the essay contemplating the nature of death. She instinctively looks for “the enemy against which he struggled” out of doors where the work has ominously stopped, the “horses stood still;” the repetition of “still” emphasizes the change to come as the world waits in anticipation, and the power – oh the power! – has “massed outside indifferent, impersonal.” The narrator’s view of death comes clear through her diction: it “moved one strangely” and “filled me with wonder”: death is an enemy, at once part and separate from us just as she is at once part and separate from (and often indifferent to) the moth’s struggles. The chilling “O yes, he seemed to say, death is stronger than I am,” is both the message of the moth and the narrator to the specter of death. The context of the essay’s publication, occurring one year after her own suicide by drowning, only magnifies the unease of the claim the essay makes: “It was useless to try to do anything…nothing, I knew, had any chance against death.” The “useless” pencil referred to repeatedly throughout the essay is lifted but not empowered to do anything but record the grim scene. Woolf, Virginia. “The Death of the Moth.” The Norton Reader: an Anthology of Expository Prose, Ninth Edition. Ed. Linda H. Peterson, John C. Brereton, and Joan E. Hartman. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996. 1267-1269. Print. Discussion questions: Track the use of pronouns throughout the essay. How does this stylistic choice signal the major tension of the piece? Track the movement between the three main foci in the piece: the world outside the window, the moth, and the narrator. Describe the persona of the narrator. Isolate specific images that resonate with you as a reader. What purpose do these images (visual, aural, tactile) serve? Of what purpose is the lack of action on the part of the narrator? How would her following through on her attempts to assist the moth change the intention of the essay? What conclusions does the essay make about the nature of death? Based on what evidence? Consider the different connotations or implications if the creature had been a butterfly instead of a moth. Compare to Dillard’s piece on the giant water bug. Notice ways in which the two essays intersect and diverge in their observations of the death of a creature.