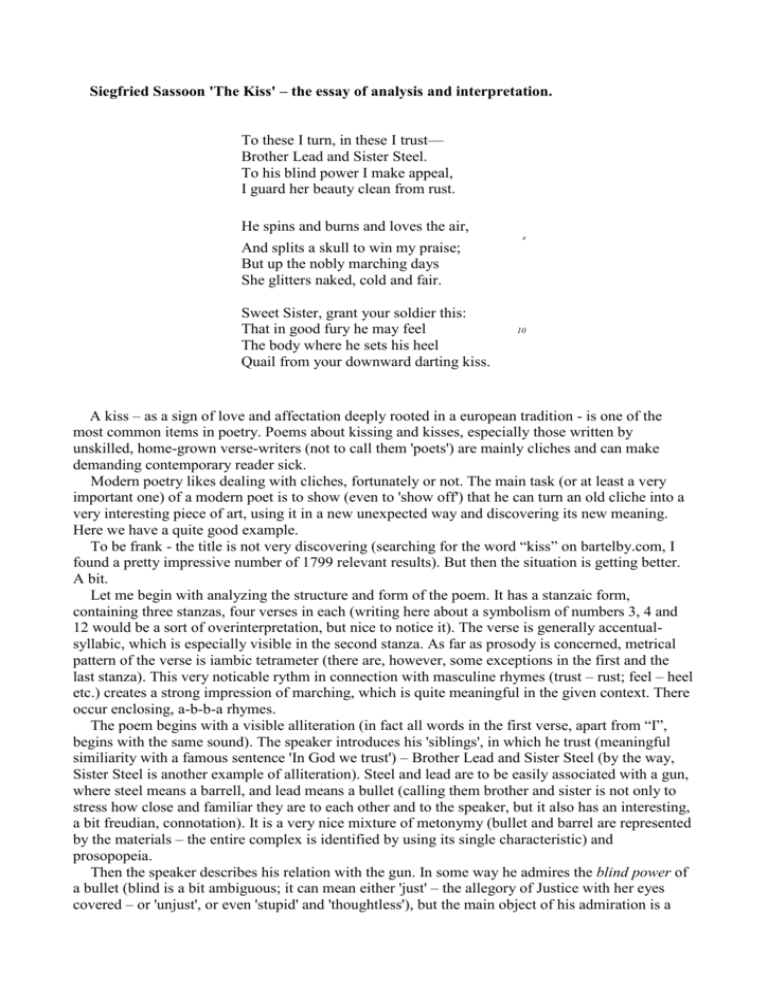

Siegfried Sassoon `The Kiss` – the essay of analysis and

advertisement

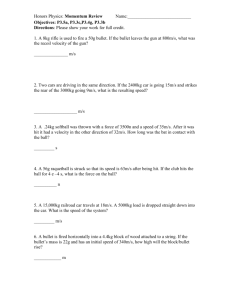

Siegfried Sassoon 'The Kiss' – the essay of analysis and interpretation. To these I turn, in these I trust— Brother Lead and Sister Steel. To his blind power I make appeal, I guard her beauty clean from rust. He spins and burns and loves the air, And splits a skull to win my praise; But up the nobly marching days She glitters naked, cold and fair. Sweet Sister, grant your soldier this: That in good fury he may feel The body where he sets his heel Quail from your downward darting kiss. 5 10 A kiss – as a sign of love and affectation deeply rooted in a european tradition - is one of the most common items in poetry. Poems about kissing and kisses, especially those written by unskilled, home-grown verse-writers (not to call them 'poets') are mainly cliches and can make demanding contemporary reader sick. Modern poetry likes dealing with cliches, fortunately or not. The main task (or at least a very important one) of a modern poet is to show (even to 'show off') that he can turn an old cliche into a very interesting piece of art, using it in a new unexpected way and discovering its new meaning. Here we have a quite good example. To be frank - the title is not very discovering (searching for the word “kiss” on bartelby.com, I found a pretty impressive number of 1799 relevant results). But then the situation is getting better. A bit. Let me begin with analyzing the structure and form of the poem. It has a stanzaic form, containing three stanzas, four verses in each (writing here about a symbolism of numbers 3, 4 and 12 would be a sort of overinterpretation, but nice to notice it). The verse is generally accentualsyllabic, which is especially visible in the second stanza. As far as prosody is concerned, metrical pattern of the verse is iambic tetrameter (there are, however, some exceptions in the first and the last stanza). This very noticable rythm in connection with masculine rhymes (trust – rust; feel – heel etc.) creates a strong impression of marching, which is quite meaningful in the given context. There occur enclosing, a-b-b-a rhymes. The poem begins with a visible alliteration (in fact all words in the first verse, apart from “I”, begins with the same sound). The speaker introduces his 'siblings', in which he trust (meaningful similiarity with a famous sentence 'In God we trust') – Brother Lead and Sister Steel (by the way, Sister Steel is another example of alliteration). Steel and lead are to be easily associated with a gun, where steel means a barrell, and lead means a bullet (calling them brother and sister is not only to stress how close and familiar they are to each other and to the speaker, but it also has an interesting, a bit freudian, connotation). It is a very nice mixture of metonymy (bullet and barrel are represented by the materials – the entire complex is identified by using its single characteristic) and prosopopeia. Then the speaker describes his relation with the gun. In some way he admires the blind power of a bullet (blind is a bit ambiguous; it can mean either 'just' – the allegory of Justice with her eyes covered – or 'unjust', or even 'stupid' and 'thoughtless'), but the main object of his admiration is a barrell, described as feminine and beautiful. Keeping it (her) clean from rust means not only caring for it (her), but may also mean frequently using the gun (there is a sort of common belief, that device frequently used tends not to rust). In the second stanza 'masculine' and 'feminine' factors of the gun are strongly distinguished and divided (which – again – has some Freudian connotation and can mean that the relation between both – the gun and the speaker and the barrel and the bullet – is almost sexual). Masculine factor – Brother Lead, the bullet, is active: he spins, burnes and loves (obviously sexual allusion) the air (description of a flying bullet), even splits a skull (alliteration again) to win the speaker's praise. It is indeed a very masculine way of acting – being active in order to impress other people (not necesserily a woman, but also another man). Notice, that it is HE, a bullet, who kills with malice and cruelty, who does the 'bad job'. The conjunction 'but' introduces the opposition between him and her – the barrel. She is static, glittering with beauty, naked (a symbol of innocence) and cold (indiffirent). Morally OK. Even days are not just passing around her, but nobly marching (yes, Freud would have a lot to say about the speaker's imprisoned subconciousness). The third stanza is almost a prayer. The masculine factor disappears, only She – Sweet Sister Steel (what a heavy alliteration) remains. In a form of apostrophe the speaker makes an appeal to her, calling himself – interesting – her soldier, which signifies his feeling of inferiority towards her. It is not a soldier who rules his weapon, but the reverse! The speaker almost prays to the weapon to let him feel fear and axiety of his victims. Notice, that he kills with a great malice – kills a lying man, pressing his body with his heel, treading on him. What can we say about the speaker? Definitely he is a dangerous maniac. One may assume that he is a soldier, but probably he is not (in a warfare one simply doesn't have time to kill his enemies 'in person', with such a malice). He is rather a murderer. And here we come to the conclusion. The last – and the most important – word of the poem is 'kiss', a repetition of the title. But now it has maybe not very new, but uncommon meaning – the kiss is in fact death; in addition quite unpleasant one, by being shot. The simile of death and love, kiss or sex is shocking, but in fact it's pretty old, beginning (to my knowledge) with the New Testament, where the kiss of Judas and Jesus was a sign of deceit and incoming death. Also the metaphore 'kiss of death' is quite familiar to our western tradition. Well, in fact Sassoon doesn't discover any new meaning of life or death, but – mainly because of interesting sexual relation between a man and a gun described, I find his poem quite worth reading.