Determinants of Crude Oil Prices - United States Association for

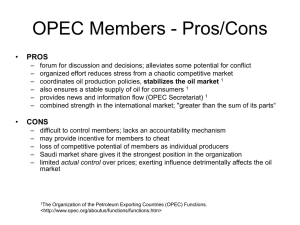

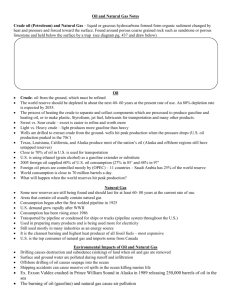

advertisement

Determinants of crude oil prices between 1997-2011 Nourah AlYousef Associate professor of Economics King Saud University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia E:mail: alyousefn@yahoo.com Phone:+966565166788 Keywords Oil prices, Oil demand, Oil supply, OPEC, Speculation. Overview The controversy over the causes of the rise in the price of crude oil is a subject of debate. One view is that oil price behavior is due to fundamental supply and demand factors. Other explanations refer to the market power OPEC, the crude oil producers. Lastly, it is the result of the major increase in oil derivatives trading over the past decade. Arguments have been offered both in favor and against of all three theories, Krichene (2006) and Dees et al. (2007) attempt to explain the rise in oil price using macroeconomic supply and demand frameworks. Other analysts emphasize the dynamic demand by emerging economies, most notably China and India. Advocates of market fundamental, who emphasize the importance of global production maximum (peak oil), refer to supply shortfalls as drivers behind oil price movements. Dees et al. (2008) and Kaufmann and Ullman (2009) focus on OPEC power and the role of speculation. Papers arguing that at least some oil price movements in recent years have been due to speculation Include: Einloth (2009), Phillips and Yu (2010), and Shu-ping (2011) . The four determinants of oil prices are not necessarily separate from each other but can go together or complement one another as shown by Hamilton (2008) and Dees et al. (2008. Hamilton (2008) used the major factors to explain the causation for changes in oil prices as follows: Whenver rate of increase in supply is far less than the rate of increase in demand speculation about future supply shortage will occur. Fattouh(2007) Hamilton (2008) and Dees et al. (2008) show that all four theories do not necessarily contradict, but rather complement one. This paper examines four major determinants of crude oil prices between 1997-2011 using quarterly data. 1-Demand side, fast-growing demand due to high global economic growth. 2-Supply side, declining non-OPEC supply. 3-Factors relating to the structure of the crude oil market and the coordinated action on the part of crude oil producer. 3- Factors associated with the behavior of financial market participants (speculation). Financial market participants are more actively engaging in commodity markets, thereby causing deviations from the equilibrium price. This study presents some stylized facts about the recent development of crude oil prices The first section discusses the four factors of possible determinants in light of the current theoretical and empirical literature: supply, demand, market power and investor behavior. Section 2 presents a detailed description of the determinants used in the empirical section of this paper. Section 3 compares these variables using cointegration analysis and quantifies the relative importance of each factor. Finally, section 4 discusses the results and presents conclusion. 1.1 Demand: The price of crude oil experienced wide price swings in times of shortage or oversupply for the period 1997 to 2011. The crude oil price cycle extended over several years responding to changes in demand as well as to other factors. Crude oil prices increased from 11 dollar in December 1998 to reach 34 in November 2000 1 to decline again to $19/B in December 2001 to rise once more to $36/B in February 2003 and continue rising to hit an all-time high of $145 a barrel in July 2008 followed by sharp decline to $ 39/B in February 2009. By March 2009 the price rose once more to reach 110 in April 2011 and continues to average $ 62/B in 2009, $ 80/B in 2010 and $95/B in 2011. One major cause of the rise or decline of oil prices are fundamentals of the market: 1. The decline in demand in 1997 as a result of the Asian crisis combined the increase of supply caused by the OPEC agreement signed in Jakarta, Indonesia, in November 1997, which raised output by 10 percent; both factors have been widely viewed as the source of the 1998 price decline to a level of $ 11/Barrel. 2. By September 2000 prices have reached $35/Bas a result of the economic recovery of the US economy. Economy, which resulted in an increase in demand in the US, the largest consumer of (25% of total oil demand) Figure 1 and Figure 2. 3. By November and December prices have declined to $19/ Barrel as a result of the recession of 2001-2002 in the US Economy and an increase of Russian oil production. 4. In 2003 prices were steadily increasing, reaching $40–50 by September 2004 as a result of increasing demand of Asian Countries mainly China and India. 5. The price of oil underwent a significant decrease after the record peak of US$145 it reached in July 2008, the lowest since the financial crisis of 2007–2010 began, and traded between US$35 a barrel and US$82 a barrel in 2009. 6. On 31 January 2011, the Brent price hit $100 a barrel for the first time since October 2008, on concerns about the political unrest in the Middle East. 7. The increases in crude oil prices since the beginning of 2011 appear to be related to a tightening world supply-demand balance and concerns over geopolitical issues that have impacted, or have the potential to impact supply flows from the Middle East and North Africa.” The growing demand in 1999 , 2000, 2003-2007 and 2010 from the industrial world and emerging markets mainly China, India, the Middle East and Latin America is a major factor for the oil price surge. The relationship between the sharp price decline in 1998, 2001, the second half of 2008 , plus the 2009 recession and the rapid slump in demand is even more apparent. A parallel movement of crude oil prices and economic growth have a tendency to be common. Most of recent studies argue that demand represents a major driving force behind the increase in oil price since 2003 (Hamilton, 2008; Hicks and Kilian, 2009; Kilian, 2009b; Wirl, 2008). Also, the increase of oil prices in 2010 and 2011 indicate that, the fast expanding demand in emerging economies can be expected to continue to be the key determinant of crude oil prices, given the generally high income elasticity of oil demand (see also Krichene, 2006). 2 Table 1: Growth in oil supply and oil demand between (1997-2011) Supply 1997 74,219 1998 75,680 1999 74,853 2000 77,768 2001 77,686 2002 76,994 2003 79,598 2004 83,105 2005 84,595 2006 84,661 2007 84,543 2008 85,507 2009 84,389 2010 86,006 2011 87,109 Source: www.eia.doe.gov 1.97% -1.09% 3.89% -0.11% -0.89% 3.38% 4.41% 1.79% 0.08% -0.14% 1.14% -1.31% 1.92% 1.28% Demand 73,450 74,104 75,791 76,772 77,512 78,160 79,722 82,511 84,105 85,255 86,288 85,776 84,337 86427 87,421 0.89% 2.28% 1.29% 0.96% 0.84% 2.00% 3.50% 1.93% 1.37% 1.21% -0.59% -1.68% 2.48% 1.15% 1.2 Supply Oil is an exhaustible resource. Thus, scarcity rents and continuously increasing prices are expected to happen According to Hotelling (1931), the price of an exhaustible resource increases over time. During the period 2003-2007, there was a sudden increase in supply from 79.5 mb/d in 2003 to 83.1mb/d as a response to the increase in oil prices; however between 2005-2007 the supply stagnated in spite of price hikes that offered a major incentive to increase production. Growing demand met with what was noticeably an increasingly limited supply. This decline in the rate of increase in supply supports the peak oil hypothesis, which indicates that production of oil has reached its maximum and future will show continuously declining production quantities (Schindler and Zittel, 2008). In reality, annual discoveries of crude oil have been declining as the number of rigs for example has dropped from 554 in 1988 to 137 rigs in 2002. But with the increase in oil prices they started increasing gradually to reach 379 rigs in 2008 and 591 rigs in 2010. This latest increase in oil discoveries were met by a low rate of growth in production (Table 2). The IEA reports (2008) point out that non-OPEC oil 3 production has stagnated since 2004 and that the increase in the global supply of crude oil is coming from OPEC countries alone Arguments against thepeak oil hypothesis in the literature are the continual improvements in technologies, which include techniques for improving oil recovery from existing fields as well as procedures that reduce the enormous costs involved in the extraction of unconventional oil resources (oil sand, oil shale, heavy oils, liquid gas, deep sea oil, Arctic oil, etc.). 1.3 OPEC Power in the world oil market: The increase of supply following the OPEC agreement signed in Jakarta, Indonesia, in November 1997, which raised output by 10 percent combined with Asian crisis have been widely considered the source of the 1998 price decline to a level of $ 11/Barrel. However, despite the OPEC meeting in April 1998, where OPEC countries agreed to voluntarily cut production, to a level of 27.5 MMB/d had no impact on the price because of the economic slowdowns of Asian countries affected the demand for oil. OPECs major producer, Saudi Arabia, cooperated with Venezuela and Mexico after a meeting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to manage supply. In October 1999 he price of crude oil has more than doubled, to reach $23.45 a barrel compared to $11 in December 1998. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries adopted in 2000 a $22/B to $28/B price band, requiring its members to cut or raise output in an effort to keep prices in that range for an OPEC basket of crudes. The policy quickly proved unsuccessful as prices increased rapidly, more than to reach $35 in September 2000, then falling until the end of 2001 before steadily increasing, reaching $40–50 by September 2004. OPEC member states account for 40% of global crude oil production, 55% of crude oil exports, and more than two-thirds of the world’s crude oil reserves (OPEC, 2009)1. The difference between current and potential production suggests that OPEC will influence on the world oil market. In effect, sustained by the tight supply situation resulting from fundamental factors as defined above, OPEC has already experienced a restoration of its market power. Since the eighties OPECs role weakened as a result of declining of OPEC market share in the world oil market, an increase of efficiency usage of energy and the development of efficient spot markets. However by 2003 OPEC experienced a revival of its market power driven by surging demand. OPECs aim is to moderate the price of oil in order to maintain oil as a vital source of energy. Thereby, OPEC increases production when price is high and decreases it when price is low. (Alyousef (1998) 1.4 Speculation: The unprecedented surge in the spot price of crude oil during 2003-08 and 2010-2011 sparked a heated public debate about the determinants of the price of oil. The popular view was that the surge in the price of oil during 2003-08 and 2010-2011 could not be explained by economic fundamentals. Instead, it was caused by what has been called the "financialization" of oil futures markets, with speculators becoming a major determinant of prices. This interpretation led to calls from politicians to regulate oil futures markets. In theory, prices on futures markets could raise prices on spot markets, where real oil is bought and sold. Some studies (Kaufmann and Ullman, 2009) indicate (or give indication or provide evidence) that the change in the relationship between spot and futures markets, observed over a number of years, and the long-term uptrend in prices triggered by fundamental market developments have been exacerbated by speculation. Triulzi, D'Ecclesia, and Bencivenga, (2010) confirm the worries expressed by consumers about the extreme volatility of the oil price induced by speculation and by the erratic trend of the dollar/euro exchange rate. Moreover, Stevans and Sessions (2008) and Acharya et al. (2009) provide evidence that, crude oil inventory holdings and futures prices do show a positive correlation and thus also influence prices on the spot market. Büyüksahin et al. (2011), stated that “fundamental data as well as the increased activity of hedge funds and other financial market participants are responsible for the stronger cointegration of futures contracts with near and far terms.” However most studies do not support that speculation as cause of the increase in oil prices, Alquist and Gervais(2011) explain that oil-price fluctuations in terms of large and persistent demand shocks are related 1 Energy information administration, Washington.. www.eia,doe,gov 4 to growth in global real activity in the presence of supply constraints. Reports on a survey by economists Lutz Kilian, Bassam Fattouh and Lavan Mahadeva (2012), emphasize that, futures and spot prices reflect “common economic fundamentals.” There is strong evidence that the co-movement between spot and futures prices reflects common economic fundamentals rather than the financialization of oil futures markets. Not only was the surge in the real price of oil well under way by 2005. But also the ability of economic fundamentals such as unexpectedly strong demand for crude oil from emerging Asia. The four determinants of oil prices are not necessarily separate from each other but can go together or complement one another. Hamilton (2008) and Dees et al. (2008) show that all four theories work together, where they can be considered as complements to each other. Hamilton (2008) used the major factors to explain the causation for changes in oil prices which can be discussed as follows: When the rate of increase in supply is far less than the rate of increase in demand speculation about future supply shortage will occur. Methods To determine the factors influencing crude oil prices, we estimate the price equation described by Kaufmann et al. (2004) and Dees et al (2008) who used quarterly data , from 1986- and from 1986-2006 respectively. This paper will use quarterly data from 1997 to 2011 and expand the model to include indicators for declining growth of non-OPEC supply and growth in China demand. Most of the variables are expressed in natural logarithms in order to estimate their elasticities. So the equation will be in which Price is the real WTI (2000 US$). Price =βo+β1 Days+β2 caputil+β3 Refine +β4 (NYMEX4-NYMEX1)+β5 gNon-opecsupply+β6 W GDP+ut Days is days of forward consumption of OECD crude oil stocks, which is calculated by dividing OECD stocks of crude oil by OECD demand for crude oil. Caputil is capacity utilization by OPEC, which is calculated by dividing OPEC production by OPEC capacity, multiplying this quotient by OPEC’s share of global oil production, and dividing this product by the rate at which OPEC cheats on its quota (dividing the difference between OPEC production and OPEC quota by world oil demand). Refine is the US refinery utilization rate. NYMEX4 is the fourth month contract for WTI and NYMEX1 is the near month contract for WTI. g is the growth in non-OPEC supply, and W GDP the world GDP. We expect the regression coefficient associated with Days to be negative — an increase in stocks reduces real oil price by reducing reliance on current production and thereby lowering the risk premium that is associated with a supply disruption. We also expect a negative relationship between refinery utilization rates and crude oil prices. This effect can be understood in two ways. Increasing rates of refinery utilization forces refiners to buy crudes that are less well suited to refineries. This reduces their yield and reduces the value of products they produce. Similarly, as refineries reach capacity, the demand for crude oil drops, We expect a negative relationship between growth rate of non-OPEC supply and crude oil prices and a positive relationship between China demand and crude oil prices. The traditional approach to determining long run and short run relationships among variables has been to use the standard Johanson Cointegration and VECM framework, but this approach suffers from serious flaws as discussed by Pesaran et al. (2001). We adopt the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) framework popularized by Pesaran and Shin (1995, 1999), Pesaran, et al. (1996), and Pesaran (2010) to establish the direction of causation between variables. The ARDL method yields consistent and robust results both for the long-run and short-run relationship between trade balance and various policy variables. This approach does not involve pretesting variables, which means that the test for the existence of relationships between variables is applicable irrespective of whether the underlying regressors are purely I(0), purely I(1), or a mixture of both. Results The elements of the cointegrating vector have signs that are generally consistent with what was expected. The effect of Days is negative. An increase in stocks reduces reliance on current production, which tends to lower the risk premium that is associated with a supply disruption. Capacity utilization by OPEC producers has a positive effect on prices. The signs of the regression coefficients are consistent with a priori expectations that prices drop rapidly at low levels of capacity utilization and rise rapidly at high levels of capacity utilization. As expected, the coefficient associated with the difference between the four-month and 5 near month contract for WTI on the New York Mercantile Exchange is positive, indicating that contango has a positive effect on prices. Finally, the coefficient associated with refinery utilization rates is negative. The decline of non-OPEC supply growth caused prices to increase. The growth of China demand has a positive effect on crude oil prices. Conclusions The changes in the price of crude oil between 1997 and 2011 have been difficult to explain with only fundamentals related to the supply/demand balance. This paper investigates additional factors that might have contributed to the oil price increase. The analysis to date does not support the proposition that speculative activity has effected changes in oil prices. Speculators play a significant role as they provide liquidity and assist in the price discovery, however , there is little-to-no evidence that the increased role of speculators drives prices. The changes in oil prices between January 1997 and December 2011 are largely due to fundamental supply and demand factors. 6 References Alquist, Ron, and Olivier Gervais. 2011. “The Role of Financial Speculation in Driving the Price of Crude Oil.” Working paper. Bank of Canada. Al-Yousef, N.A.,(1998) "Saudi Arabia. Oil policy 1976-1996." PhD thesis. University of Surry , Guildford U.K. Büyükşahin, Bahattin, and Jeffrey H. Harris. 2011. “Do Speculators Drive Crude Oil Futures?” Energy Journal 32: 167-202 Dées, S. Gasteuil, A. Kaufmann, R. and Mann, M. (2008) “Assessing the factors behind oil price changes” Working paper NO 855. Dees, S. P. Karadeloglou, R. Kaufmann, and M. Sanchez (2007), Modelling the World Oil Market, Assessment of a quarterly Econometric Model, Energy Policy, 35, 178-191. Einloth, J.T(2009), Speculation and Recent Volatility in the Price of Oil” Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1488792 Fattouh, B. (2007 The Drivers of Oil Prices:The Usefulness and Limitations of NonStructural Model, the Demand–Supply Framework and Informal Approaches Discussion Paper 71 SOAS, University of London. Fattouh. B. Kilian, L. Mahadeva, L (2012) The Role of Speculation in Oil Markets: What Have We Learned So Far? http://www-personal.umich.edu/~lkilian/milan030612.pdf Fattouh, Bassam. 2010a. “Oil Market Dynamics through the Lens of the 2002-2009 Price Cycle.” OIES Working Paper 39, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Fattouh, Bassam. 2010b. “The Dynamics of Crude Oil Differentials.” Energy Economics 32: 334-342. Fattouh, Bassam, and Pasquale Scaramozzino. 2011. “Uncertainty, Expectations, and Fundamentals:Whatever Happened to Long-Term Oil Prices?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27: 186-206 Hamilton, J. 2008. Understanding Crude Oil Prices. Working Paper 14492. National Bureau of Economic Research. 7 Hamilton, J. 2009. “Causes and Consequences of the Oil Shock of 2007–08.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring): 215–61 Holland, S.P. (2008), “Modelling Peak Oil”, The Energy Journal 29: 61-79 Kaufmann RK, Ullman B (2009) . Oil prices, speculation and fundamentals: interpreting causal relationship among spot and futures prices. Energy Economics. 31: 550-558 Kaufmann, R.K. Bradford, A. Belanger,L, H. Mclaughlin J. P,, and Miki Y. (2008) “Determinants of OPEC production: Implications for OPEC behavior” Energy Economics .30: 333–351 Kaufmann, R.K, S. Dees, P. Karadeloglou, and M. Sanchez (2004), Does OPEC matter? An econometric analysis of oil prices, The Energy Journal, 25(4), 67-90. Krichene, N. (2006) “Recent Dynamics of Crude Oil Prices” IMF working paper WP/06/299 Pesaran and Shin (1995, 1998), An autoregressive distributed lag modeling approach to cointegration analysis. DAE Working papers, No.9514. Pesaran et al. (1996), Testing for the existence of a long run relationship. DAE Working papers, No.9622. Pesaran, Shin and Smith, (2001), “Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships” Journal of Applied Econometrics. 16: 289–326. Peseran, M. H., Peseran, B. (2010). Time Series Econometrics using Microfit 5.0, Oxford: Oxford University Press Phillips, Peter C.B. and Jun Yu(2010), “Dating the Timeline of Financial Bubbles during the Subprime Crisis,” Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper 1770, Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics 2010. Shu-ping S. and V, Arora(2011) “An application of models of speculative behaviour of oil prices: CAMA Working Paper 11/2011 Triulzi, U., D'Ecclesia,R. Bencivenga, C.,(2010) (“Does speculation drive oil prices? http://www.idra.it/garnetpapers/C15U_Triulzi_R_L_DEcclesia_C_Bencivenga.pdf 8