doc format - Skyline College

advertisement

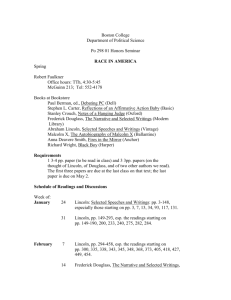

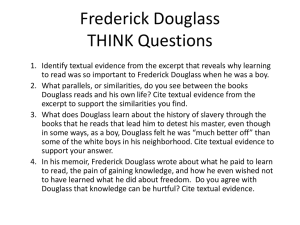

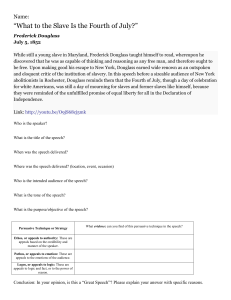

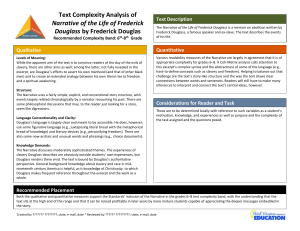

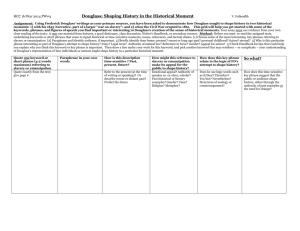

What, Why, and How? 2 CRITICAL THINKING Definition and rationale Breaking down critical thinking into categories Bloom’s Taxonomy Applying higher and lower levels of thinking in writing WHAT IS CRITICAL THINKING? Critical thinking is a set of skills designed to help the thinker analyze, assess and question a given situation or reading. Critical thinking skills push the thinker to reject simplistic conclusions based on human irrationality, false assumptions, prejudices, biases and anecdotal evidence. Critical thinking skills give thinkers confidence that they can see issues which are complex and which have several answers and points of view and that opinions and insights can change with new information. WHAT DO CRITICAL THINKERS DO? Consider all sides of an issue Judge well the quality of an argument Judge well the credibility of sources Create convincing arguments using sound evidence and analysis Effectively recognize and use ethos (ethics), pathos (empathy) and logos (logic) in argument WHY IS IT IMPORTANT? People will listen to and respect critical thinkers with these abilities because… Considering all sides of an issue means they are open-minded, informed, and mindful of alternatives and other points of view. Judging well the quality of an argument means they can effectively identify and evaluate another’s reasons, assumptions and conclusions and not be fooled into believing false or unsubstantiated claims. Judging well the credibility of sources means they can recognize and present the most reputable, trustworthy and convincing evidence. Creating convincing arguments using sound evidence and analysis means they can formulate plausible hypotheses and draw conclusions which are thoughtful and verifiable. Effectively recognizing and using ethos, pathos and logos in argument means they construct well-crafted points using a balance of morality and ethics, consideration and empathy for others, as well as sound and logical reasoning. HOW DO I USE CRITICAL THINKING? Breaking down into categories how to analyze a topic or text (one written by you or another author) will help you examine it thoroughly and critically. Use these questions to assist you: Clarity: Is it understandable and can the meaning be clearly grasped? Is the main idea clear? Can examples be added to better illustrate the points? Are there confusing or unrelated points? Accuracy: Is it free from errors or distortions—is it true? Do I need to verify the truth of the claims? Is credible evidence used correctly and fairly? Is additional research needed? Precision: Is it exact with specific details? Can the wording be more exact? Are the claims too general? Are claims supported with concrete evidence? Relevance: How does it relate to the topic or assignment? Does it help illuminate the topic or assignment? Does it provide new or important information? Who does the content have the most relevance for? Depth: Does it contain complexities and delve into the larger implications? What are some of the complexities explored? What are some of the difficulties that should be addressed? What are the larger implications or impact? Breadth: Does it encompass multiple viewpoints? Do I need to look at this from another perspective? What other people would have differing viewpoints? Do I need to look at this in other ways? Logic: Do the parts make sense together and are there no contradictions? Do all the points work together logically to prove one clear argument? Does one paragraph follow logically from the next? Does the evidence directly prove the main points? Significance: Does it focus on what is important? Is this the most important aspect to consider? Which of the facts or points are the most important? Does it examine a larger significance? Fairness: Is it justifiable and not self-serving or one-sided? Do I have any vested interest in this issue that can affect my reaction? Is personal bias or a hidden agenda driving the point? Are the viewpoints of others sympathetically represented? PRACTICE Clarity: Is it understandable and can the meaning be clearly grasped? Is the main idea clear? Can examples be added to better illustrate the points? Are there confusing or unrelated points? Relevance: How does it relate to the topic or assignment? Does it help illuminate the topic or assignment? Does it provide new or important information? Who does the content have the most relevance for? Logic: Do the parts make sense together and are there no contradictions? Do all the points work together logically to prove one clear argument? Does one paragraph follow logically from the next? Does the evidence directly prove the main points? Use this chart to help you apply these critical thinking categories to a particular text or topic: Accuracy: Is it free from errors or distortions—is it true? Precision: Is it exact with specific details? Do I need to verify the truth of the claims? Is credible evidence used correctly and fairly? Is additional research needed? Can the wording be more exact? Are the claims too general? Are claims supported with concrete evidence? Depth: Does it contain complexities and delve into the larger implications? Breadth: Does it encompass multiple viewpoints? What are some of the complexities explored? What are some of the difficulties that should be addressed? What are the larger implications or impact? Do I need to look at this from another perspective? What other people would have differing viewpoints? Do I need to look at this in other ways? Significance: Does it focus on what is important? Fairness: Is it justifiable and not self-serving or one-sided? Is this the most important aspect to consider? Which of the facts or points are the most important? Does it examine a larger significance? Do I have any vested interest in this issue that can affect my reaction? Is personal bias or a hidden agenda driving the point? Are the viewpoints of others sympathetically represented? Bloom’s Taxonomy Benjamin Bloom, a well-respected American educational psychologist, headed a group who developed a classification of levels of intellectual behavior important in learning. The image of the pyramid gives a visual of how lower level thinking builds up to higher level thinking. This hierarchy shows how a critical thinker can build upon and consciously employ multiple levels of thinking and learning: Create: can you create a new product or point of view? CREATE Verbs: assemble, construct, create, design, develop, formulate, write, film, program, generate, produce, invent, publish Evaluate: can you justify a stand or decision? Verbs: appraise, argue, defend, judge, determine, select, support, decide, critique, comment EVALUATE Analyze: can you distinguish between the different parts? ANALYZE Verbs: compare, contrast, differentiate, distinguish, examine, question, test, explore, deconstruct, synthesize, appraise Apply: can you use the information in a new way? APPLY Verbs: choose, demonstrate, dramatize, employ, illustrate, interpret, operate, schedule, sketch, solve, use, implement Understand: can you explain ideas or concepts? UNDERSTAND Verbs: describe, discuss, explain, identify, recognize, report, annotate, paraphrase, restate, summarize Remember: can you recall the information? REMEMBER Verbs: define, duplicate, list, state, memorize, recall, repeat, reproduce PRACTICE Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Analyze a Text When you analyze a text, you want to be able to employ all of the levels of thinking. Let’s take a look at a passage from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart. Just about this time, I got hold of a book entitled The Columbian Orator. Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book. Among much of other interesting matter, I found in it a dialogue between a master and his slave. The slave was represented as having run away from his master three times. The dialogue represented the conversation which took place between them, when the slave was retaken the third time. In this dialogue, the whole argument in behalf of slavery was brought forward by the master, all of which was disposed of by the slave. The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master—things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master. Either using this passage from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass or your current reading assignment, fill in an example sentence (in the white boxes below) that demonstrates each level of thinking. An example has been included for each level to guide you. Create: Douglass reveals how this long Create: and brutal control of human beings was partly accomplished through control over literacy, so the school programs today with large numbers of African-Americans need to be analyzed and restructured so we can end the virtual enslavement that persists due to inequities in education. Evaluate: Evaluate: Though Frederick Douglass lived more than a century ago, his drive to learn is still one of the best habits one can have, but unfortunately this drive today is rare as people are increasingly lazy and apathetic. Analyze: Douglass’ situation can be compared to Analyze: poor illiterate women in Pakistan today who are not allowed to attend school so are unaware of their own rights and are often mistreated and abused as a result. Apply: Apply: Students can learn from Douglass how powerful and life changing the art of persuasion and using lessons from history can be. Understand: Understand: Douglass’ revelation that one could disagree with the justifications for slavery was rare because slaves were not allowed to read or become educated. Remember: Remember: Douglass was inspired by a book he read where the slave convinced his master that slavery was wrong. APPLYING THE LEVELS OF THINKING IN YOUR WRITING Now that we have looked at the hierarchy of low level to high level thinking, you as an academic writer want to make sure that your writing includes and is lead by the higher level skills of analyzing, evaluating and creating and does not get stuck solely in the lower levels of remembering (defining and repeating) and understanding (reporting and summarizing). In academic writing, you want a balance of higher and lower order thinking but be sure to LEAD the paper with higher order thinking so reporting and summarizing does not take over your paper. EXAMPLE Here is a paragraph from the sample essay on Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The higher levels of thinking are in bold and the lower levels of thinking are not: After secretly learning to read and write on his own, Douglass discovered that freeing his mind led to anguished torment as he was unable to free himself from the entrenched institutions of slavery, but change at least was set in motion. Initially, being awakened to the stark realities of his condition served to plunge Douglass into despair: “As I read and contemplated the subject, behold! that very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish” (84). Once Douglass’s eyes were opened, he invariably suffered: “… I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out. In moments of agony, I envied my fellow-slaves for their stupidity” (84). So is ignorance bliss? The answer for us to live in a fair and decent world has to be no, never. To be ignorant allows others not only to make choices for you but to limit your choices without you even realizing it. Not knowing the factors and people who shape your life, enables those in power to act in their own self-interest and have no accountability when doing so. It also makes people unable to recognize when they are victimized by unjust situations, and if you cannot see the problem, then you can never demand change. After Douglass understood the evils of slavery, he suffered initially and even entertained thoughts of suicide, but later he escaped to the north and became an influential leader in the abolitionist movement and spent the remainder of his life fighting for the equality and rights of blacks as well as women. Higher levels of thinking lower levels of thinking Higher levels of thinking lower levels of thinking PRACTICE Identifying Higher and Lower Levels of Thinking Using this paragraph from an essay written on The Autobiography of Malcolm X, underline the parts that demonstrate higher order thinking: The diligence and persistent effort Malcolm X showed in learning to read has become disappointingly rare. Malcolm X in his autobiography tells us that when he went to prison, he could hardly read or write. He decided the way to improve would be to copy the entire dictionary word for word by hand. He said to copy just the first page alone took an entire day. The next day he reviewed all the words he did not remember, so he slowly built his vocabulary, and at the same time he started educating himself about the larger world as he describes the dictionary as a “miniature encyclopedia” (2). Malcolm X carried on until he copied the entire dictionary cover to cover. However, the time he dedicated to his writing was not confined to this amazing achievement alone: “Between what I wrote in my tablet, and writing letters, during the rest of my time in prison I would guess I wrote a million words” (2). The dedication to his own education and how he strengthened his own intelligence and abilities through sheer force of will is impressive but unfortunately is the exception rather than the norm. In Generation Me, the author Jean Twenge addresses the present generation of people who have been taught to put themselves first and expect instant results without working hard to achieve them. Twenge states: “They are less likely to work hard today to get a reward tomorrow—an especially important skill these days, when many good jobs require graduate degrees” (157). If people are less willing today to work hard, then we are going to have increasingly uneducated, lazy people who spend more time complaining than achieving. With a lack of education we won’t be strong critical thinkers so will be easily taken in by people who want to exploit us for profit like advertisers and corporate America. Instead of defining who we are, people who want to sell us things will continue to shape our wants, desires and perceptions of ourselves. ANSWERS Using this paragraph from an essay on Malcolm X’s autobiography, underline the parts that demonstrate higher order thinking: The diligence and persistent effort Malcolm X showed in learning to read has become disappointingly rare. Malcolm X in his autobiography tells us that when he went to prison, he could hardly read or write. He decided the way to improve would be to copy the entire dictionary word for word by hand. He said to copy just the first page alone took an entire day. The next day he reviewed all the words he did not remember, so he slowly built his vocabulary, and at the same time he started educating himself about the larger world as he describes the dictionary as a “miniature encyclopedia” (2). Malcolm X carried on until he copied the entire dictionary cover to cover. However, the time he dedicated to his writing was not confined to this amazing achievement alone: “Between what I wrote in my tablet, and writing letters, during the rest of my time in prison I would guess I wrote a million words” (2). The dedication to his own education and how he strengthened his own intelligence and abilities through sheer force of will is impressive but unfortunately is the exception rather than the norm. In Generation Me, the author Jean Twenge addresses the present generation of people who have been taught to put themselves first and expect instant results without working hard to achieve them. Twenge states: “They are less likely to work hard today to get a reward tomorrow—an especially important skill these days, when many good jobs require graduate degrees” (157). If people are less willing today to work hard, then we are going to have increasingly uneducated, lazy people who spend more time complaining than achieving. With a lack of education we won’t be strong critical thinkers so will be easily taken in by people who want to exploit us for profit like advertisers and corporate America. Instead of defining who we are, people who want to sell us things will continue to shape our wants, desires and perceptions of ourselves.