TOURTELLOTTE MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL

advertisement

TOURTELLOTTE MEMORIAL

HIGH SCHOOL

ENGLISH MANUAL

1

GLOSSARY

STARTING THE WRITING PROCESS

3

PARAGRAPHS

5

TRANSITION WORDS AND PHRASES

8

TRANSITIONAL DEVICES

10

INTRODUCTORY PARAGRAPHS

12

CREATING A THESIS STATEMENT

16

DEVELOPING A THESIS

18

DEVELOPING AN OUTLINE

20

THEMES

23

UNIVERSAL THEMES IN LITERATURE

24

WRITING ABOUT LITERATURE

25

WRITING ABOUT FICTION

29

HOW TO WRITE A CRITICAL ANALYSIS

35

ANALYZING A RHETORICAL ARGUMENT

36

WRITING A RESEARCH PAPER

37

WORDS TO DESCRIBE CHARACTERS

94

ACTIVE VERBS

95

GLOSSARY OF LITERARY TERMS

100

HELPFUL LINKS

107

BIBLIOGRAPHY

108

2

Themes

While there are no infallible rules about inferring theme, there are several guidelines that

can help any reader discover this elusive element of fiction. Answers to these questions

will help.

Has the main character changed in any way? If so, what has this character learned

about life?

What is the central conflict? What is its outcome?

How does the title relate to the meaning of the story?

Guidelines for Expressing Theme

1. Once you think you know what the main topic of the story is (for instance, loyalty

to country, motherhood, etc.), you need to express it in statement form. THEME

IS A STATEMENT ABOUT THIS TOPIC. Thus, the theme of a story might be,

“Loyalty to country sometimes requires self-sacrifice.”

2. Theme should be stated as a generalization about life. Do not use the names of the

characters or refer to precise places of events.

3. While themes are generalizations, readers must not make the generalization larger

than the story justifies. Beware of words like every, all, always. Terms like some,

sometimes, may are often more accurate.

4. THEME is the central and unifying concept of the story. Be sure that your

statement of theme

Accounts for all the major details of the story

Is not contradicted by any detail of the story

Is based on data from the story itself and not on assumptions supplied

from our own experience.

5. Avoid expressing THEME as a cliché: “You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

“Honesty is the best policy.”

3

Universal Themes in Literature

Definition of Theme

The theme of a piece of fiction is its controlling idea or its central insight. In

order to figure out theme, a reader must ask what view of life a work supports or what

insight into life in the real world it reveals.

Definition of Universal Theme

Frequently, a work of fiction implies a few ideas about the nature of all men and

women or about the relationship of human beings to each other or to the universe. These

are called universal themes.

Examples of Universal Themes

As expressed by authors, themes involve positions on these familiar issues:

A human being’s confrontation with nature

A human being’s lack of humanity

A rebellious human being’s confrontation with a hostile society

An individual’s struggle toward understanding, awareness, and/or spiritual

enlightenment

An individual’s conflict between passion and responsibility

The human glorification of the past/ rejection of the past

The tension between the ideal and the real

Conflict between human beings and machines

The impact of the past on the present

The inevitability of fate

The evil of unchecked ambition

The struggle for equality

The loss of innocence/disillusionment of adulthood

The conflict between parents and children

The making of an artist in a materialistic society

The clash between civilization and the wilderness

The clash between appearance and realities

The pain of love (or what passes for it)

The perils or rewards of carpe diem

4

Close Reading of a Literary Passage

To do a close reading, you choose a specific passage and analyze it in fine detail, as if

with a magnifying glass. You then comment on points of style and on your reactions as a

reader. Close reading is important because it is the building block for larger analysis.

Your thoughts evolve not from someone else's truth about the reading, but from your own

observations. The more closely you can observe, the more original and exact your ideas

will be. To begin your close reading, ask yourself several specific questions about the

passage. The following questions are not a formula, but a starting point for your own

thoughts. When you arrive at some answers, you are ready to organize and write. You

should organize your close reading like any other kind of essay, paragraph by paragraph,

but you can arrange it any way you like.

I. First Impressions:

What is the first thing you notice about the passage?

What is the second thing?

Do the two things you noticed complement each other? Or contradict each other?

What mood does the passage create in you? Why?

II. Vocabulary and Diction:

Which words do you notice first? Why? What is noteworthy about this diction?

How do the important words relate to one another?

Do any words seem oddly used to you? Why?

Do any words have double meanings? Do they have extra connotations?

Look up any unfamiliar words. For a pre-20th century text, look in the Oxford

English Dictionary for possible outdated meanings. (The OED can only be

accessed by students with a subscription or from a library computer that has a

subscription. Otherwise, you should find a copy in the local library.)

III. Discerning Patterns:

Does an image here remind you of an image elsewhere in the book? Where?

What's the connection?

How might this image fit into the pattern of the book as a whole?

Could this passage symbolize the entire work? Could this passage serve as a

microcosm--a little picture--of what's taking place in the whole work?

What is the sentence rhythm like? Short and choppy? Long and flowing? Does it

build on itself or stay at an even pace? What is the style like?

Look at the punctuation. Is there anything unusual about it?

Is there any repetition within the passage? What is the effect of that repetition?

5

How many types of writing are in the passage? (For example, narration,

description, argument, dialogue, rhymed or alliterative poetry, etc.)

Can you identify paradoxes in the author's thought or subject?

What is left out or kept silent? What would you expect the author to talk about

that the author avoided?

IV. Point of View and Characterization:

How does the passage make us react or think about any characters or events

within the narrative?

Are there colors, sounds, physical description that appeals to the senses? Does this

imagery form a pattern? Why might the author have chosen that color, sound or

physical description?

Who speaks in the passage? To whom does he or she speak? Does the narrator

have a limited or partial point of view? Or does the narrator appear to be

omniscient, and he knows things the characters couldn't possibly know? (For

example, omniscient narrators might mention future historical events, events

taking place "off stage," the thoughts and feelings of multiple characters, and so

on).

V. Symbolism:

Are there metaphors? What kinds?

Is there one controlling metaphor? If not, how many different metaphors are there,

and in what order do they occur? How might that be significant?

How might objects represent something else?

Do any of the objects, colors, animals, or plants appearing in the passage have

traditional connotations or meaning? What about religious or biblical

significance?

If there are multiple symbols in the work, could we read the entire passage as

having allegorical meaning beyond the literal level?

6

How to Do a Close Reading

The process of writing an essay usually begins with the close reading of a text. Of course,

the writer's personal experience may occasionally come into the essay, and all essays

depend on the writer's own observations and knowledge. But most essays, especially

academic essays, begin with a close reading of some kind of text—a painting, a movie, an

event—and usually with that of a written text. When you close read, you observe facts

and details about the text. You may focus on a particular passage, or on the text as a

whole. Your aim may be to notice all striking features of the text, including rhetorical

features, structural elements, cultural references; or, your aim may be to notice only

selected features of the text—for instance, oppositions and correspondences, or particular

historical references. Either way, making these observations constitutes the first step in

the process of close reading.

The second step is interpreting your observations. What we're basically talking about here

is inductive reasoning: moving from the observation of particular facts and details to a

conclusion, or interpretation, based on those observations. And, as with inductive

reasoning, close reading requires careful gathering of data (your observations) and careful

thinking about what these data add up to.

How to Begin:

1. Read with a pencil in hand, and annotate the text.

"Annotating" means underlining or highlighting key words and phrases—anything that

strikes you as surprising or significant, or that raises questions—as well as making notes

in the margins. When we respond to a text in this way, we not only force ourselves to pay

close attention, but we also begin to think with the author about the evidence—the first

step in moving from reader to writer.

Here's a sample passage by anthropologist and naturalist Loren Eiseley. It's from his

essay called "The Hidden Teacher."

. . . I once received an unexpected lesson from a spider. It happened far

away on a rainy morning in the West. I had come up a long gulch

looking for fossils, and there, just at eye level, lurked a huge yellowand-black orb spider, whose web was moored to the tall spears of

buffalo grass at the edge of the arroyo. It was her universe, and her

senses did not extend beyond the lines and spokes of the great wheel

she inhabited. Her extended claws could feel every vibration

throughout that delicate structure. She knew the tug of wind, the fall of

a raindrop, the flutter of a trapped moth's wing. Down one spoke of the

web ran a stout ribbon of gossamer on which she could hurry out to

investigate her prey.

7

Curious, I took a pencil from my pocket and touched a strand of the

web. Immediately there was a response. The web, plucked by its

menacing occupant, began to vibrate until it was a blur. Anything that

had brushed claw or wing against that amazing snare would be

thoroughly entrapped. As the vibrations slowed, I could see the owner

fingering her guidelines for signs of struggle. A pencil point was an

intrusion into this universe for which no precedent existed. Spider was

circumscribed by spider ideas; its universe was spider universe. All

outside was irrational, extraneous, at best raw material for spider. As I

proceeded on my way along the gully, like a vast impossible shadow, I

realized that in the world of spider I did not exist.

2. Look for patterns in the things you've noticed about the text—repetitions,

contradictions, similarities.

What do we notice in the previous passage? First, Eiseley tells us that the orb spider

taught him a lesson, thus inviting us to consider what that lesson might be. But we'll let

that larger question go for now and focus on particulars—we're working inductively. In

Eiseley's next sentence, we find that this encounter "happened far away on a rainy

morning in the West." This opening locates us in another time, another place, and has

echoes of the traditional fairy tale opening: "Once upon a time . . .". What does this

mean? Why would Eiseley want to remind us of tales and myth? We don't know yet, but

it's curious. We make a note of it.

Details of language convince us of our location "in the West"—gulch, arroyo, and

buffalo grass. Beyond that, though, Eiseley calls the spider's web "her universe" and "the

great wheel she inhabited," as in the great wheel of the heavens, the galaxies. By

metaphor, then, the web becomes the universe, "spider universe." And the spider, "she,"

whose "senses did not extend beyond" her universe, knows "the flutter of a trapped

moth's wing" and hurries "to investigate her prey." Eiseley says he could see her

"fingering her guidelines for signs of struggle." These details of language, and others,

characterize the "owner" of the web as thinking, feeling, striving—a creature much like

ourselves. But so what?

3. Ask questions about the patterns you've noticed—especially how and why.

To answer some of our own questions, we have to look back at the text and see what else

is going on. For instance, when Eiseley touches the web with his pencil point—an event

"for which no precedent existed"—the spider, naturally, can make no sense of the pencil

phenomenon: "Spider was circumscribed by spider ideas." Of course, spiders don't have

ideas, but we do. And if we start seeing this passage in human terms, seeing the spider's

situation in "her universe" as analogous to our situation in our universe (which we think

of as the universe), then we may decide that Eiseley is suggesting that our universe (the

universe) is also finite, that our ideas are circumscribed, and that beyond the limits of our

8

universe there might be phenomena as fully beyond our ken as Eiseley himself—that

"vast impossible shadow"—was beyond the understanding of the spider.

But why vast and impossible, why a shadow? Does Eiseley mean God, extra-terrestrials?

Or something else, something we cannot name or even imagine? Is this the lesson? Now

we see that the sense of tale telling or myth at the start of the passage, plus this reference

to something vast and unseen, weighs against a simple E.T. sort of interpretation. And

though the spider can't explain, or even apprehend, Eiseley's pencil point, that pencil

point is explainable—rational after all. So maybe not God. We need more evidence, so

we go back to the text—the whole essay now, not just this one passage—and look for

additional clues. And as we proceed in this way, paying close attention to the evidence,

asking questions, formulating interpretations, we engage in a process that is central to

essay writing and to the whole academic enterprise: in other words, we reason toward our

own ideas.

Copyright 1998, Patricia Kain, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

9

How to Mark a Book

http://slowreads.com/ResourcesHowToMarkABook-Outline.htm

This outline addresses why you would ever want to mark in a book. For each reason, the

outline gives specific strategies to achieve your goals in reading the book. (Click here to

read the essay that this outline was created for.)

1. Interact with the book – talk back to it. You learn more from a conversation

than you do from a lecture. (This is the text-to-self connection.)

a. Typical marks

i. Question marks and questions – be a critical reader

ii. Exclamation marks – a great point, or I really agree!

iii. Smiley faces and other emoticons

iv. Color your favorite sections. Perhaps draw pictures in the margin

that remind you about the passage’s subject matter or events.

v. Pictures and graphic organizers. The pictures may express your

overall impression of a paragraph, page, or chapter. The graphic

organizer (Venn diagram, etc.) may give you a handy way to sort

the material in a way that makes sense to you.

b. Typical writing

i. Comments – agreements or disagreements

ii. Your personal experience

1. Write a short reference to something that happened to you

that the text reminds you of, or that the text helps you

understand better

2. Perhaps cross-reference to your diary or to your personal

journal (e.g., “Diary, Nov. 29, 2004”)

iii. Random associations

1. Begin to trust your gut when reading! Does the passage

remind you of a song? Another book? A story you read?

Like some of your dreams, your associations may carry

more psychic weight than you may realize at first. Write

the association down in the margin!

2. Cross-reference the book to other books making the same

point. Use a shortened name for the other book – one

you’ll remember, though. (e.g., “Harry Potter 3”) (This is a

text-to-text connection.)

2. Learn what the book teaches. (This is the text-to-world connection.)

a. Underline, circle or highlight key words and phrases.

b. Cross-reference a term with the book’s explanation of the term, or where

the book gives the term fuller treatment.

i. In other words, put a reference to another page in the book in the

margin where you’re reading. Use a page number.

10

ii. Then, return the favor at the place in the book you just referred to.

You now have a link so you can find both pages if you find one of

them.

c. Put your own summaries in the margin

i. If you summarize a passage in your own words, you’ll learn the

material much better.

ii. Depending on how closely you wish to study the material, you may

wish to summarize entire sections, paragraphs, or even parts of

paragraphs.

iii. If you put your summaries in your books instead of separate

notebooks, the book you read and the summary you wrote will

reinforce each other. A positive synergy happens! You’ll also

keep your book and your notes in one place.

d. Leave a “trail” in the book that makes it easier to follow when you study

the material again.

i. Make a trail by writing subject matter headings in the margins.

You’ll find the material more easily the second time through.

ii. Bracket or highlight sections you think are important

e. In the margin, start a working outline of the section you’re reading. Use

only two or three levels to start with.

f. Create your own index in the back of the book! Click here to see an

example of a homemade index.

i. Don’t set out to make a comprehensive index. Just add items that

you want to find later.

ii. Decide on your own keywords – one or two per passage. What

would you look for if you returned to the book in a few days? In a

year?

iii. Use a blank page or pages in the back. Decide on how much space

to put before and after the keyword. If your keyword starts with

“g,” for instance, go about a quarter of the way through the page or

pages you’ve reserved for your index and write the word there.

iv. Write down the keyword and the page number on which the

keyword is found. If that isn’t specific enough, write “T,” “M,” or

“B” after the page number. Each of those letters tells you where to

look on the page in question; the letters stand for “top,” “middle,”

and “bottom,” respectively.

v. Does the book already have an index? Add to it with your own

keywords to make the index more useful to you.

g. Create a glossary at the beginning or end of a chapter or a book.

i. Every time you read a word you don’t know that seems important

for your purposes in reading the book, write it down in your

glossary.

ii. In your glossary next to the word in question, put the page number

where the word may be found.

iii. Put a very short definition by each word in the glossary.

3. Pick up the author’s style. (This is the reading-to-writing connection.)

11

a. Why? Because you aren’t born with a writing style. You pick it up.

Perhaps there’s something that you like about this author’s style but you

don’t know what it is. Learn to analyze an author’s writing style in order

to pick up parts of her style that becomes natural to you.

b. How?

i. First, reflect a bit. What do you like about the writer’s style? If

nothing occurs to you, consider the tone of the piece (humorous,

passionate, etc.) Begin to wonder: how did the writer get the tone

across? (This method works for discovering how a writer gets

across tone, plot, conflict, and other things.)

ii. Look for patterns.

1. Read a paragraph or two or three you really like. Read it

over and over. What begins to stand out to you?

2. Circle or underline parts of speech with different colored

pens, pencils, or crayons. Perhaps red for verbs, blue for

nouns, and green for pronouns.

3. Circle or underline rhetorical devices with different colored

writing instruments, or surround them with different

geometric shapes, such as an oval, a rectangle, and a

triangle.

a. What rhetorical devices?

i. How she mixes up lengths of sentences

ii. Sound devices – alliteration, assonance,

onomatopoeia, repetition, internal rhymes,

etc.

iii. You name it!

iii. Pick a different subject than that covered in the passage, and

deliberately try to use the author’s patterns in your own writing.

iv. Put your writing aside for a few days, and then edit it. What

remains of what you originally adopted from the writer’s style? If

what remains is natural and well done, you may have made that

part of her style part of your own style.

12

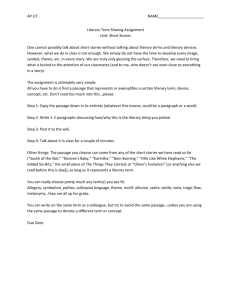

Steps for Close Reading or Explication de texte:

Patterns, polarities, problems, paradigm, puzzles, perception

An explication de texte (cf. Latin explicare, to unfold, to fold out, or to make clear the meaning of)

is a finely detailed, very specific examination of a short poem or short selected passage from a

longer work, in order to find the focus or design of the work, either in its entirety in the case of the

shorter poem or, in the case of the selected passage, the meaning of the microcosm,

containing or signaling the meaning of the macrocosm (the longer work of which it is a part).

To this end "close" reading calls attention to all dynamic tensions, polarities, or problems in the

imagery, style, literal content, diction, etc. By examining and thinking about opening up the way

the poem or work is perceived, writers establish a central pattern, a design that orders the

narrative and that will, in turn, order the organization of any essay about the work. Coleridge

knew about this method when he referred to the "germ" of a work of literature (see Biographia

Literaria). Very often, the language creates a visual dynamic as well as verbal coherence.

Close Reading or Explication de texte operates on the premise that literature, as artifice, will

be more fully understood and appreciated to the extent that the nature and interrelations of its

parts are perceived, and that that understanding will take the form of insight into the theme of the

work in question. This kind of work must be done before you can begin to appropriate any

theoretical or specific literary approach. Follow these instructions so you don't follow what Mrs.

Arable says about the magical web of Charlotte's in Charlotte's Web, "I don't understand it, and I

don't like what I don't understand."

Follow these steps before you begin writing. These are pre-writing steps,

procedures to follow, questions to consider before you commence actual

writing. Remember that the knowledge you gain from completing each of

the steps is cumulative. There may be some information that overlaps, but

do not take shortcuts. In selecting one passage from a short story, poem, or novel, limit

your selection to a short paragraph (4-5 sentences), but certainly no more than one paragraph.

When one passage, scene, or chapter of a larger work is the subject for explication, that

explication will show how its focused-upon subject serves as a macrocosm of the entire work—a

means of finding in a small sample patterns which fit the whole work.

If you follow these 12 steps to literary awareness, you will find a new

and exciting world. Do not be concerned if you do not have all the answers to the

questions in this section. Keep asking questions; keep your intellectual eyes open to new

possibilities.

1. Figurative Language. Examine the passage carefully for similes, images, metaphors,

and symbols. Identify any and all. List implications and suggested meanings as well as

denotations. What visual insights does each word give? Look for mutiple meanings and

overlapping of meaning. Look for repetitions, for oppositions. See also the etymology of

each word because you may find that the word you think you are familiar with is actually

13

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

dependent upon a metaphoric concept. Consider how each word or group of words

suggests a pattern and/or points to an abstraction (e.g., time, space, love, soul, death).

Can you visualize the metaphoric world? Are there spatial dimensions to the language?

Diction. This section is closely connected with the section above. Diction, with its

emphasis on words, provides the crux of the explication. Mark all verbs in the passage,

mark or list all nouns, all adjectives, all adverbs etc. At this point it is advisable that you

type out the passage on a separate sheet to differentiate each grammatical type.

Examine each grouping. Look up as many words as you can in a good dictionary, even if

you think that you know the meaning of the word. The dictionary will illuminate new

connotations and new denotations of a word. Look at all the meanings of the key words.

Look up the etymology of the words. How have they changed? The words will begin to

take on multistable meanings. Be careful to always check back to the text, keeping

meaning contextually sound. Do not assume you know the depth or complexity of

meaning at first glance. Rely on the dictionary, particularly the Oxford English Dictionary.

Can you establish a word web of contrastive and parallel words? Do dictionary meanings

establish any new dynamic associations with other words? What is the etymology of

these words? Develop and question the metaphoric, spatial sense of the words. Can you

see what the metaphoric words are suggesting?

Literal content: this should be done as succinctly as possible. Briefly describe the

sketetal contents of the passage in one or two sentences. Answer the journalist's

questions (Who? What? When? Where? Why?) in order to establish character/s, plot,

and setting as it relates to this passage. What is the context for this passage?

Structure. Divide the passage into the more obvious sections (stages of argument,

discussion, or action). What is the interrelation of these units? How do they develop?

Again, what can you postulate regarding a controlling design for the work at this point? If

the work is a poem, identify the poetic structure and note the variations within that

structure. In order to fully understand "Scorn Not the Sonnet," you must be

knowledgeable about the sonnet as a form. What is free verse? Is this free verse or blank

verse? What is the significance of such a form? Does the form contribute to the

meaning? How does the theatrical structure of Childress's young adult novel, A Hero Ain't

Nothin' But a Sandwich, enhance the narrative?

Style. Look for any significant aspects of style—parallel constructions, antithesis, etc.

Look for patterns, polarities, and problems. Periodic sentences, clause structures?

Polysyndeton etc.? And reexamine all postulates, adding any new ones that occur to you.

Look for alliteration, internal rhymes and other such poetic devices which are often used

in prose as well as in poetry. A caesura? Enjambment? Anaphora? Polysyndeton? You

need to look closely here for meanings that are connected to these rhyme schemes.

Characterization. What insight does this passage now give into specific characters as

they develop through the work? Is there a persona in this passage? Any allusions to

other literary characters? To other literary works that might suggest a perspective. Look

for a pattern of metaphoric language to give added insight into their motives and feelings

which are not verbalized. You should now be firming up the few most important

encompassing postulates for the governing design of the work, for some overriding

themes or conflicts.

Tone. What is the tone of the passage? How does it elucidate the entire passage? Is the

tone one of irony? Sentimental? Serious? Humorous? Ironic?

Assessment. This step is not to suggest a reduction; rather, an "close reading" or

explication should enable you to problematize and expand your understanding of the text.

Ask what insight the passage gives into the work as a whole. How does it relate to

themes, ideas, larger actions in other parts of the work? Make sure that your hypothesis

regarding the theme(s) of the work is contextually sound. What does it suggest as the

polarity of the whole piece?

14

9. Context: If your text is part of a larger whole, make brief reference to its position in the

10.

11.

12.

whole; if it is a short work, say, a poem, refer it to other works in its author's canon,

perhaps chronologically, but also thematically. Do this expeditiously.

Texture: This term refers to all those features of a work of literature which contribute to

its meaning or signification, as distinguished from that signification itself: its structure,

including features of grammar, syntax, diction, rhythm, and (for poems, and to some

extent) prosody; its imagery, that is, all language which appeals to the senses; and its

figuration, better known as similes, metaphors, and other verbal motifs.

Theme: A theme is not to be confused with thesis; the theme or more properly themes of

a work of literature is its broadest, most pervasive concern, and it is contained in a

complex combination of elements. In contrast to a thesis, which is usually expressed in a

single, arugumentative, declarative sentence and is characteristic of expository prose

rather than creative literature, a theme is not a statement; rather, it often is expressed in

a single word or a phrase, such as "love," "illusion versus reality," or "the tyranny of

circumstance." Generally, the theme of a work is never "right" or "wrong." There can be

virtually as many themes as there are readers, for essentially the concept of theme refers

to the emotion and insight which results from the experience of reading a work of

literature. As with many things, however, such an experience can be profound or trivial,

coherent or giddy; and discussions of a work and its theme can be correspondingly

worthwhile and convincing, or not. Everything depends on how well you present and

support your ideas. Everything you say about the theme must be supported by the brief

quotations from the text. Your argument and proof must be convincing. And that, finally,

is what explication is about: marshaling the elements of a work of literature in such a

way as to be convincing. Your approach must adhere to the elements of ideas,

concepts, and language inherent in the work itself. Remember to avoid phrases and

thinking which are expressed in the statement, "what I got out of it was. . . ."

Thesis: An explication should most definitely have a thesis statement. Do not try to write

your thesis until you have finished all 12 steps. The thesis should take the form, of

course, of an assertion about the meaning and function of the text which is your subject.

It must be something which you can argue for and prove in your essay.

Conclusion. Now, and only now are you ready to begin your actual writing. If you find that

what you had thought might be the theme of the work, and it doesn't "fit," you must then go back

to step one and start over. This is a trial and error exercise. You learn by doing. Finally, the

explication de texte should be a means to see the complexities and ambiguities in a given

work of literature, not for finding solutions and/or didactic truisms.

15

What is Close Reading?

1. Close reading is the most important skill you need for any form of literary studies.

It means paying especially close attention to what is printed on the page. It is a much

more subtle and complex process than the term might suggest.

2. Close reading means not only reading and understanding the meanings of the

individual printed words; it also involves making yourself sensitive to all the nuances

and connotations of language as it is used by skilled writers.

3. This can mean anything from a work's particular

vocabulary,

sentence construction, and imagery, to the themes that are being dealt with, the way

in which the story is being told, and the view of the world that it offers. It involves

almost everything from the smallest

issues of literary understanding and judgement.

linguistic items to the largest

4. Close reading can be seen as four separate levels of attention which we can bring

to the text. Most normal people read without being aware of them, and employ all

four simultaneously. The four levels or types of reading become progressively more

complex.

Linguistic - You pay

especially close attention to the surface

linguistic elements of the text - that is, to

aspects of

vocabulary,

grammar, and syntax. You might also note

such things as figures of speech or any other

features which contribute to the writer's

individual style.

Semantic - You take account at a deeper

level of what the words mean - that is, what

information they yield up, what meanings

16

they denote and connote.

Structural - You note the possible

relationships between words within the text and this might include items from either the

linguistic or semantic types of

reading.

Cultural - You note the relationship of any

elements of the text to things outside it.

These might be other pieces of writing by the

same author, or other writings of the same

type by different writers. They might be

items of social or cultural history, or even

other academic disciplines which might seem

relevant, such as philosophy or psychology.

5. Close reading is not a skill which can be developed to a sophisticated extent

overnight. It requires a lot of practice in the various

linguistic and

literary disciplines involved - and it requires that you do a lot of reading. The good

news is that most people already possess the skills required. They have acquired

them automatically through being able to read - even though they havn't been

conscious of doing so. This is rather like many other things which we learn

unconsciously. After all, you don't need to know the names of your leg muscles in

order to walk down the street.

6. The four types of reading also represent increasingly complex and sophisticated

phases in our scrutiny of the text.

Linguistic reading is largely

descriptive. We are noting what is in the text

and naming its parts for possible use in the

next stage of reading.

Semantic reading is cognitive. That is, we

need to understand what the words are

telling us - both at a surface and maybe at an

17

implicit level.

Structural reading is analytic. We must

assess, examine, sift, and judge a large

number of items from within the text in their

relationships to each other.

Cultural reading is interpretive. We offer

judgements on the work in its general

relationship to a large body of cultural

material outside it.

7. The first and second of these stages are the sorts of activity designated as

'Beginners' level; the third takes us to 'Intermediate'; and the fourth to 'Advanced'

and beyond.

8. One of the first things you need to acquire for serious literary study is a knowledge

of the vocabulary, the technical language, indeed the jargon in which literature is

discussed. You need to acquaint yourself with the technical

of the discipline and then go on to study how its parts work.

vocabulary

9. What follows is a short list of features you might keep in mind whilst reading. They

should give you ideas of what to look for. It is just a prompt to help you get under

way.

Close reading - Checklist

Grammar

The relationships of the words in sentences

Vocabulary

The author's choice of individual words

Figures of speech

The rhetorical devices used to give

18

decoration and imaginative expression to

literature, such as simile or metaphor

Literary devices

The devices commonly used in literature to

give added depth to the work, such as

imagery or symbolism

Tone

The author's attitude to the subject as

revealed in the manner of the writing

Style

The author's particular choice and

combination of all these features of writing

which creates a recognisable and distinctive

manner of writing.

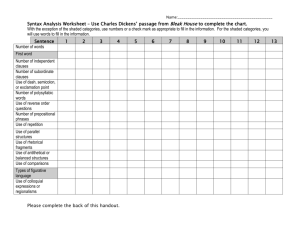

10. Now here's an example of close reading in action. The short passage which

follows comes from the famous opening to Charles Dickens' Bleak House.

11. If you would like to treat this as an interactive exercise, read the passage through

a number of times. Make notes, and write down all you can say about what goes to

make up its literary 'quality'. That is, you should scrutinise the passage as closely as

possible, name its parts, and say what devices the author is using. Don't be afraid to

list even the most obvious points.

12. If you are not really sure what all this means however, allow yourself a brief

glance ahead at the first couple of discussion notes which follow, and then come back

to carry on making notes of your own.

13. Don't worry if you are not sure what name to give to any feature you notice. You

will see the technical

vocabulary being used in the discussion notes

which follow, and this should help you pick up this skill as we go along.

Bleak House

London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and

19

the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn

Hall. Implacable November weather. As

much mud in the streets, as if the waters had

but newly retired from the face of the earth,

and it would not be wonderful to meet a

Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling

like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.

Smoke lowering down from chimney pots,

making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of

soot in it as big as full grown snowflakes gone into mourning, one might imagine, for

the death of the sun.

14. This is the sort of writing which many people, asked for their first impressions,

would say was very 'descriptive'. But if you looked at it closely enough you will have

seen that it is imaginative rather than descriptive. It doesn't 'describe what is there' but it invents images and impressions. There is as much "it was as if ..." material in

the extract as there is anything descriptive. What follows is a close reading of the

extract, with comments listed in the order that they appear in the extract.

London

This is an abrupt and astonishingly short 'sentence' with which to start a six hundred

page novel. In fact technically, it is grammatically incomplete, because it does not

have a verb or an object. It somehow implies the meaning 'The scene is London.'

Sentence construction

In fact each of the first four sentences here are 'incomplete' in this sense. Dickens is

taking liberties with conventional grammar - and obviously he is writing for a literate

and fairly sophisticated readership.

Sentence length

These four sentences vary from one word to forty-three words in length. This helps to

create entertaining variation and robust flexibility in his prose style.

Michaelmas Term

There are several names (proper nouns) in these sentences, all signalled by capital

letters (London, Michaelmas Term, Lord Chancellor, Lincoln's Inn Hall, November,

Holborn Hill). This helps to create the very credible and realistic world Dickens

presents in his fiction. We believe that this is the same London which we could visit

20

today. The names also emphasise the very specific and concrete nature of the world

he creates.

Michaelmas Term

This occurs in autumn. It comes from the language of the old universities (Oxford

and Cambridge) which is shared by the legal profession and the Church.

Lord Chancellor sitting

Here 'sitting' is a present participle. The novel is being told in the present tense at

this point, which is rather unusual. The effect is to give vividness and immediacy to

the story. We are being persuaded that these events are taking place now.

Implacable

This is an unusual and very strong term to describe the weather. It means 'that which

cannot be appeased'. What it reflects is Dickens's genius for making almost

everything in his writing original, striking, and dramatic.

as if

This is the start of his extended simile comparing the muddy streets with the

primeval world.

the waters

There is a slight Biblical echo here, which also fits neatly with the idea of an ancient

world he is summoning up.

but newly and wonderful

These are slightly archaic expressions. We might normally expect 'recently' and

'astonishing' but Dickens is selecting his vocabulary to suit the subject - the

prehistoric world. 'Wonderful' is being used in its original sense of - 'something we

wonder at'.

forty feet long or so

After the very specific 'forty feet long', the addition of 'or so' introduces a slightly

conversational tone and a casual, almost comic effect.

waddling

This reinforces the humorous manner in which Dickens is presenting this

Megalosaurus - and note the breadth of his vocabulary in naming the beast with such

scientific precision.

like an elephantine lizard

This is another simile, announced by the word 'like'. Here is Dickens's skill with

language yet again. He converts a 'large' noun ('elephant') into an adjective

21

('elephantine') and couples it to something which is usually small ('lizard') to

describe, very appropriately it seems, his Megalosaurus.

up Holborn Hill

There is a distinct contrast, almost a shock here, in this abrupt transition from an

imagined prehistoric world and its monsters to the 'real' world of Holborn in

London.

lowering

This is another present participle, and an unusual verb. It means 'to sink, descend, or

slope downwards'. It comes from a rather 'poetic' verbal register, and it has a

softness (there are no sharp or harsh sounds in it) which makes it very suitable for

describing the movement of smoke.

soft black drizzle

He is comparing the dense smoke (from coal fires) with another form of particularly

depressing atmosphere - a drizzle of rain. Notice how he goes on to elaborate the

comparison.

as big as full grown snow flakes

The comparison becomes another simile: 'as big as'. And then 'full grown' almost

suggests that the snowflakes are human. This is a device much favoured by Dickens:

it is called 'anthropomorphism' - attributing human qualities or characteristics to

things which are themselves inanimate. Then 'snowflakes' is a well-observed

comparison for an enlarged flake of soot, because they are of similar size and texture.

Notice next how Dickens immediately goes on to play with the notion that whilst soot

is black, snowflakes are white.

gone into mourning

This reinforces the anthropomorphism. The inanimate world is being brought to life.

And of course 'mourning' reinforces the atmospheric gloom he is trying to evoke. It

also introduces blackness (the colour of mourning) to explain how these snowflakes

(actually flakes of soot) might have changed from white to black.

the death of the sun

This is why the flakes have changed colour. And if the sun has died the light and life

it brings to earth have also been extinguished - which reinforces the atmosphere of

pre-historic darkness he is creating.

15. We will stop at this point. It would in fact be possible to say even more about the

extract if we were to relate it to the novel as a whole - but almost everything listed

was accessible even if you were reading the passage for the first time.

22

16. Literary studies are not conducted in such detail all the time, but it is very

important that you try to develop the skill of reading as closely as possible. It really is

the foundation on which everything else is based.

17. The next point to make about such close reading is that it becomes easier if you

get used to the idea of reading and re-reading. The Russian novelist Vladimir

Nabokov (famous for Lolita) once observed that "Curiously enough, one cannot read

a book: one can only re-read it".

18. What he meant by this apparently contradictory remark is that the first time we

read a book we are busy absorbing information, and we cannot appreciate all the

subtle connexions there may be between its parts - because we don't yet have the

complete picture before us. Only when we read it for a second time (or even better, a

third or fourth) are we in a position to assemble and compare the nuances of

meaning and the significance of its details in relation to each other.

19. This is why the activity is called 'close reading'. You should try to get used to the

notion of reading and re-reading very carefully, scrupulously, and in great detail.

20. Finally, let's try to dispel a common misconception. Many people ask, when they

first come into contact with close reading: "Doesn't analysing a piece of work in such

detail spoil your enjoyment of it?" The answer to this question is "No - on the

contrary - it should enhance it." The simple fact is that we get more out of a piece of

writing if we can appreciate all the subtleties and the intricacies which exist within it.

Nabokov also suggested that "In reading, one should notice and fondle the details".

23

Close Reading a Text

Use these "tracking" methods to yield a richer understanding of the text and lay a solid

ground work for your thesis.

1. Use a highlighter, but only after you've read for comprehension. The point of

highlighting at this stage is to note key passages, phrases, turning points in the

story.

Pitfalls:

Highlighting too much

Highlighting without notes in the margins

2. Write marginal notes in the text.

These should be questions, comments, dialogue with the text itself.

A paragraph from Doris Lessing's short story "A Woman on a Roof" serves as an

example:

The second paragraph could have a note from the reader like this:

Marginal

Notes

Text

Why is the man annoyed

by the sunbather? Is

Lessing commenting on

sexist attitudes?

Then they saw her, between chimneys, about fifty yards

away. She lay face down on a brown blanket. They could

see the top part of her: black hair, aflushed solid back,

arms spread out.

"She's stark naked," said Stanley, sounding annoyed.

3. Keep a notebook for freewrite summaries and response entries.

Write quickly after your reading: ask questions, attempt answers and make comments

about whatever catches your attention. A good question to begin with when writing

response entries is "What point does the author seem to be making?"

4. Step back.

24

After close reading and annotating, can you now make a statement about the story's

meaning? Is the author commenting on a certain type of person or situation? What is that

comment?

Glossary of Literary Terms

Alliteration : A sound effect in which consonant sounds are repeated, particularly at the

beginnings of words or of stressed syllables.

Allusion: A reference to something (such as a character or event in literature, history, or

mythology) outside the text itself.

Ambiguity: Quality of being intentionally unclear. Events that are ambiguous can be

interpreted in more than one way. This device is particularly beneficial in poetry,

as it tends to enrich the work with the depth of multiple meanings.

Anachronism: In a story, an element that is out of its time frame, sometimes used to

create an amusing or jarring effect.

Analysis: The process of examining components of a literary work.

Anapest: The poetic foot (measure)that follows the pattern unaccented, unaccented,

accented.

Anecdote: A short and often personal story used to emphasize a point, to develop a

character or a theme, or to inject humor

Antagonist: The main opponent of the protagonist in a story, play, narrative, or dramatic

work.

Antecedent: The word or phrase to which a pronoun refers.

Anticlimax: An often disappointing, sudden end to an intense situation.

Antihero: A protagonist who carries the action of the literary piece but does not embody

the classic characteristics of courage, strength, and nobility.

Antithesis: A concept that is directly opposed to a previously presented idea.

Aphorism: A terse statement of truth, principle, or opinion.

25

Apostrophe: A rhetorical (not expecting an answer) figure of direct address to a person,

object or abstract entity. [Such as John Donne’s address to death in “Death Be

Not Proud”]

Archetype: A character, situation, or symbol that is familiar to people from all cultures

because it occurs in literature, myth, religion, or folklore.

Assonance: A sound effect in which identical or similar vowel sounds are repeated in

two or more words in close proximity to each other.

Ballad: A folk song or poem passed down orally that tells a story which may be derived

from an actual incident or from legend or folklore. Usually composed in fourlined stanzas with the rhyme scheme abcb, ballads often contain a refrain.

Blank Verse: Unrhymed poetry of iambic pentameter. (Favored technique of

Shakespeare)

Citation: A reference made in an essay, to another text. The citation may be used for

diverse purposes: to illustrate a point or idea, to add support or authority to the

writer’s argument or reasoning, to bolster reader trust in the persona, or to add

depth to the essay by expanding its range of literary reference.

Climax: The moment in the plot of a story or play at which tensions are highest or

suspense reaches its height.

Conflict: A struggle among opposing forces or characters in fiction, poetry, or drama.

Connotation: An associative or suggestive meaning of a word in addition to its literal

dictionary meaning (or denotation).

Consonance: A sound effect in which identical or similar consonant sounds, occurring in

nearby words, are repeated with different intervening vowels (ex: crush/crash)

Couplet: Two successive rhyming lines of the same number of syllables, with matching

cadence.

Dactyl: Foot of poetry with three syllables, one stressed and two short or unstressed.

Denotation: The dictionary definition of a word, without associative or implied

meanings.

Denouement: The moment of final resolution of the conflict in a plot.

Deus Ex Machina: Literally, when the gods intervene at a story’s end to resolve a

seemingly impossible conflict. Refers to an unlikely or improbable coincidence; a

cop-out ending.

26

Dialogue: The spoken conversation that occurs in a text.

Diction: Word choice. Diction can be described as formal or informal, abstract or

concrete, general or specific, and literal or figurative.

Didactic: A didactic story, speech, essay or play is one in which the author’s primary

purpose is to instruct, moralize, or teach.

English or Shakespearean Sonnet: A fourteen-line love poem in iambic pentameter

with a rhyme scheme abab, cdcd,efef,gg.

Epigraph: A brief quotation found at the beginning of a literary work, reflective of

theme.

Epiphany: A sudden flash of insight; a dramatic realization.

Epistolary Novel: A novel written in letter format by one or more characters.

Essay: A unifies and relatively short work of nonfiction prose.

An Argumentative essay advances an explicit argument and supports it with

evidence. An Expository essay informs an audience or explains a particular

subject.

Ethos: The moral element in dramatic literature that determines a character’ action rather

than his or her thoughts or emotion.

Euphemism: Substitution of an inoffensive word or phrase for another that would be

harsh, offensive, or embarrassing.

Exposition: The part of the plot of a short story or play that provides the background

information on characters, setting, and plot.

Farce: A kind of comedy that depends on exaggerated or improbable situations, physical

disasters, and/or sexual innuendo to amuse the audience

Figurative Language: The term used to encompass all non-literal uses of language.

Figure (or Trope): A word or phrase used in a way that significantly changes its

standard or literal meaning. Common kinds of figures are metaphor, simile,

irony, and paradox.

Flashback: Interruption in the chronological presentation of a narrative or drama that

presents an earlier episode.

27

Flat Character: A simple, one dimensional character who remains the same, and about

whom little or nothing is revealed throughout the course of the work.

Foil: A character whose contrasting personal characteristics draws attention to, enhance,

or contrast with those of the main character. A character who, by displaying

opposite traits, emphasizes certain aspects of another character.

Free Verse: Poetry that does not have regular rhythm or rhyme.

Genre: The category into which a piece of writing can be classified—poetry, prose,

drama. Each genre has its own conventions and standards.

Hubris: Insolence, arrogance, or pride.

Hyperbole: an extreme exaggeration for literary effect that is not meant to be interpreted

literally.

Iamb: a metrical foot consisting of a lightly stressed syllable followed by a stressed

syllable.

Iambic Pentameter: A five-foot line made up of an unaccented followed by an accented

syllable.

Imagery: Anything that affects or appeals to the reader’s senses: sight, sound, touch,

taste, or smell.

In Medias Res: In literature, a work that begins in the middle of the story.

Interior Monologue: A literary technique used in poetry and prose that reveals a

character’s unspoken thoughts and feelings.

Internal Rhyme: A rhyme that is within the line, rather than at the end.

Inversion: A switch in the normal word order, often for emphasis or for rhyme scheme.

Irony: A type of incongruity. Dramatic irony involves an incongruity between what a

characters in a story or believes and what we know. Verbal irony involves an

incongruity between what is literally said and what is actually meant.

Italian Sonnet: Fourteen-line poem divided into two parts: the first eight lines

(abbaabba) and the second is six (cdcdcd or cdecde).

Litotes: Affirmation of an idea by using a negative understatement. (The opposite of

hyperbole.)

Logos: The topics of rational (logical) argument or the arguments themselves.

Lyric Poem: A poem, usually rather short, in which a speaker expresses a state of mind

or feeling of a single speaker.

28

Metamorphosis: A radical change in a character, either physical or emotional.

Metaphor: A figure of speech which compares two dissimilar things, asserting that one

thing is another thing, not just that one is like another thing.

Meter: The rhythmic pattern of a poem. Just as all words are pronounced with accented

(or stressed) syllables, lines of poetry are assigned similar rhythms. English

poetry uses five basic metric feet:

Iamb—unstressed, stressed: before

Trochee—stressed, unstressed: weather

Anapest—unstressed, unstressed, stressed: contradict

Dactyl—stressed, unstressed, unstressed: satisfy

Spondee—equally stressed: One word spondees are very rare in the

English language; a spondaic foot is almost always two words.

Metonymy: A figure of speech that replaces the name of something with a word or

phrase closely associated with it. (Example: saying “the White House” instead of

“the president”)

Monologue: A long speech by a single character.

Myth: A story, usually with supernatural significance, that explains the origins of gods,

heroes, or natural phenomena; they also contain deeper truths, particularly about

the nature of human kind.

Narrative Poem: A poem that tells a story.

Ode: A lyric poem, composed in a lofty style, that is serious in subject and elaborate in

stanza structure.

Onomatopoeia: the formation of a word, as cuckoo or boom, by imitation of a sound

made by or associated with its referent.

Oxymoron: A figure of speech that combines two contradictory words placed side by

side: deafening silence.

Parable: A short story illustrating a moral or religious lesson.

Paradox: An apparently contradictory statement that proves, upon examination, to be

true.

Parallelism: The repeated use of the same grammatical structure in a sentence or series

of sentences. This device tends to emphasize what is said to underscore the

meaning.

29

Parody: A comical imitation of a serious piece with the intent of ridiculing the author or

his work.

Pastoral: A poem, play, or story that celebrates and idealizes the simple life of

shepherds. Also refers to an artistic work that portrays rural life in an idyllic

manner.

Pathos: The quality of a literary work or passage which appeals to the reader’s emotions.

Personification: The attribution of human characteristics to an animal or to an inanimate

object.

Point of View: Perspective of the speaker or narrator in a literary work.

First person—the story is told by the character himself/herself.

Third person limited—the story is told from the character’s point of view, but

through a narrator.

Third person omniscient—the story is told by an all-seeing narrator.

Protagonist: The main or principle character in a work; often considered the hero or

heroine.

Pun: Humorous play on words that have several meanings or words that sound the same

but have different meanings.

Quatrain: Four-lined stanza

Refrain: Repetition of a line, stanza, or phrase.

Repetition: A word or phrase used more than once to emphasize an idea.

Rhetoric- The art or science of all specialized literary uses of language in prose or verse,

including figurative language; the study of the effective use of language.

Rhetorical Question: A question with an obvious answer, so no response is expected.

Satire: The use of humor to ridicule and expose the shortcomings and failings of society,

individuals, and institutions, often in the hope that change and reform are

possible.

Sestet: A six-lined stanza of poetry; also the last six lines of an Italian sonnet.

Simile: A comparison of things using the word like, as, or so

Soliloquy: A character’s speech to the audience, in which emotions and ideas are

revealed. A monologue is a soliloquy only if the character is alone on stage.

30

Stanza: A grouping of poetic lines; a deliberate arrangement of lines in poetry.

Stock Character: A stereotypical character.

Stream of Consciousness: A form of writing that replicates the way the human mind

works. Ideas are presented in random order; thoughts are often unfinished.

Style: The way a writer uses language; takes into account word choice, diction, figures of

speech, and so on. Refers to the writer’s voice.

Symbol: A concrete object, scene, or action which has deeper significance because it is

associated with something else, often an important idea or theme in the work.

Synecdoche: A figure of speech where one part represents the entire object or vice versa.

Syntax: The way in which words, phrases, and sentences are ordered and connected.

Theme: The central idea of a literary work.

Tone: Refers to the author’s attitude toward the subject, and often sets the mood of the

piece.

Tragic Flaw: Traditionally, a defect in a hero or heroine that leads to his or her downfall.

Transition/segue: The means to get from one portion of a poem or story to another; for

instance, to another setting, to another character’s viewpoint, to a later or earlier

time period. It is a way of smoothly connecting different parts of a work.

31