Sonnet unit for creative writing

advertisement

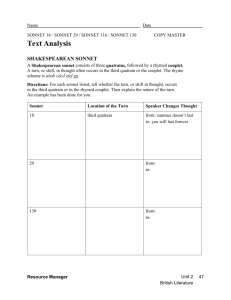

YEAR 9 & 10 CREATIVE WRITING ELECTIVE – THE SONNET 1 “The sonnet is one of the oldest verse forms in English. Used by almost every notable poet in the language, it is the best example of how rhyme and meter can provide the imagination not with a prison but with a theatre” Norton Anthology of Poetry A sonnet is a specific sort of poem with the following structure: 14 lines Iambic Pentameter Formal rhyme scheme There are five main types of sonnet: 1. Italian (Petrarchan) Rhymes abba abba (turn) cde cde using an octave and a sestet. 2. Elizabethan (Shakespearean) Rhymes abab cdcd efef (turn) gg using three quatrains and a couplet. 3. Spenserian Rhymes abab bcbc (turn) cdcd ee using three quatrains and a couplet, but with overlapping couplets between quatrains. 4. The Unidentifiables 5. Modern Sonnets No distinct rhyme scheme and irregular rhythm. Consider the following six sonnets. For each poem: 1. Identify the rhyme scheme. 2. A sonnet raises a scenario or problem, then gives a different perspective at the end (the turn). Write a paragraph identifying what is raised, and how the perspective changes and where. Quote from the poem to support your points. 2 I. The Italian (or Petrarchan) Sonnet: The basic meter of all sonnets in English is iambic pentameter although there have been a few tetrameter and even hexameter sonnets, as well. The Italian sonnet is divided into two sections by two different groups of rhyming sounds. The first 8 lines is called the octave and rhymes: abbaabba The remaining 6 lines is called the sestet and can have either two or three rhyming sounds, arranged in a variety of ways: cdcdcd cddcdc cdecde cdeced cdcedc The exact pattern of sestet rhymes (unlike the octave pattern)is flexible. In strict practice, the one thing that is to be avoided in the sestet is ending with a couplet (dd or ee), as this was never permitted in Italy, and Petrarch himself (supposedly) never used a couplet ending; in actual practice, sestets are sometimes ended with couplets (Sidney's "Sonnet LXXI given below is an example of such a terminal couplet in an Italian sonnet). The point here is that the poem is divided into two sections by the two differing rhyme groups. In accordance with the principle (which supposedly applies to all rhymed poetry but often doesn't), a change from one rhyme group to another signifies a change in subject matter. This change occurs at the beginning of L9 in the Italian sonnet and is called the volta, or "turn"; the turn is an essential element of the sonnet form, perhaps the essential element. It is at the volta that the second idea is introduced. And here is a poem by the inventor of the poem himself, Francesco Petrarch – Soleasi Nel Mio Cor She ruled in beauty o'er this heart of mine, A noble lady in a humble home, And now her time for heavenly bliss has come, 'Tis I am mortal proved, and she divine. The soul that all its blessings must resign, And love whose light no more on earth finds room, Might rend the rocks with pity for their doom, Yet none their sorrows can in words enshrine; They weep within my heart; and ears are deaf Save mine alone, and I am crushed with care, And naught remains to me save mournful breath. Assuredly but dust and shade we are, 3 Assuredly desire is blind and brief, Assuredly its hope but ends in death. Translated by Thomas Wentworth Higginson There are a number of variations which evolved over time to make it easier to write Italian sonnets in English. Most common is a change in the octave rhyming pattern from a b b a a b b a to a b b a a c c a, eliminating the need for two groups of 4 rhymes, something not always easy to come up with in English which is a rhyme-poor language. Wordsworth uses that pattern in the following sonnet, along with a terminal couplet: Scorn Not the Sonnet Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned, Mindless of its just honours; with this key Shakespeare unlocked his heart; the melody Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound; A thousand times this pipe did Tasso sound; With it Camoens soothed an exile's grief; The Sonnet glittered a gay myrtle leaf Amid the cypress wtih which Dante crowned His visionary brow: a glow-worm lamp, It cheered mild Spenser, called from Faery-land To struggle through dark ways; and when a damp Fell round the path of Milton, in his hand The Thing became a trumpet; whence he blew Soul-animating strains—alas, too few! William Wordsworth 4 II. The Elizabethan (or Shakespearian) Sonnet: The Elizabethan or English sonnet has the simplest and most flexible pattern of all sonnets, consisting of 3 quatrains of alternating rhyme and a couplet: abab cdcd efef gg Sonnet 130 My mistres eyes are nothing like the Sunne, Corrall is farre more red, than her lips red, If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun: If haires be wiers, black wiers grow on her head: I have seene Roses damaskt, red and white, But no such Roses see I in her cheeks, And in some perfumes is there more delight, Than in the breath that from my Mistres reekes. I love to heare her speake, yet well I know, That Musicke hath a farre more pleasing sound: I graunt I never saw a goddesse goe, My Mistres when shee walkes treads on the ground. And yet by heaven I thinke my love as rare, As any she belied with false compare. William Shakespeare 1609 Sonnet 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer's lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. William Shakespeare 1609 5 III. The Spenserian Sonnet: The Spenserian sonnet, invented by Edmund Spenser as an outgrowth of the stanza pattern he used in The Faerie Queene (a b a b b c b c c), has the pattern: ababbcbccdcdee Here, the "abab" pattern sets up distinct four-line groups, each of which develops a specific idea; however, the overlapping a, b, c, and d rhymes form the first 12 lines into a single unit with a separated final couplet. The three quatrains then develop three distinct but closely related ideas, with a different idea (or commentary) in the couplet. Interestingly, Spenser often begins L9 of his sonnets with "But" or "Yet," indicating a volta exactly where it would occur in the Italian sonnet; however, if one looks closely, one often finds that the "turn" here really isn't one at all, that the actual turn occurs where the rhyme pattern changes, with the couplet, thus giving a 12 and 2 line pattern very different from the Italian 8 and 6 line pattern (actual volta marked by italics): Sonnet 23 Penelope for her Ulisses sake, Deviz’d a Web her wooers to deceave: In which the worke that she all day did make The same at night she did again unreave: Such subtile craft my Damzell doth conceave, Th’ importune suit of my desire to shonne: For all that I in many dayes doo weave, In one short houre I find by her undone. So when I think to end that I begonne, I must begin and never bring to end: For with one look she spill that long I sponne, And with one word my whole years work doth rend. Such labour like the Spyders web I fynd, Whose fruitlesse worke is broken with least wynde. Edmund Spencer 1595 6 IV. The Indefinables There are, of course, some sonnets that do not fit any clear recognizable pattern but still certainly function as sonnets. Shelley's “Ozymandias” belongs to this category. Its rhyming pattern of a b a b a c d c e d e f e f is unique, however, there is a volta in Line 9 exactly as in an Italian sonnet: Ozymandias I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert . . . Near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, (stamped on these lifeless things,) The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. 7 V. The Modern Sonnet This sonnet has no distinct rhyme or rhythm. In The Park She sits in the park. Her clothes are out of date. Two children whine and bicker, tug her skirt. A third draws aimless patterns in the dirt Someone she loved once passed by – too late to feign indifference to that casual nod. “How nice” et cetera. “Time holds great surprises.” From his neat head unquestionably rises a small balloon…”but for the grace of God…” They stand a while in flickering light, rehearsing the children’s names and birthdays. “It’s so sweet to hear their chatter, watch them grow and thrive, ” she says to his departing smile. Then, nursing the youngest child, sits staring at her feet. To the wind she says, “They have eaten me alive.” Gwen Harwood 8 3, NOW WRITE YOUR OWN SONNET In some of our earlier exercises, we have used constraints In order to go beyond our first thoughts – to access the unconscious mind, in fact. The sonnet structure is another way of doing this. The constraints of content, rhythm and rhyme will make you choose words that you would not otherwise have chosen and take your poem in a direction that you might not have expected. LIST A LIST B LIST C Hovers Retreats Follows Regret Delight Distrust Stars Moon Sun Afar Higher Beyond Impressed Amazed Despairing Emerald Ruby Sapphire Choose from one of the word lists above. You must use all six words in your poem (but they can be in any order). Decide which rhyme structure you are going to adopt. Don’t forget to use iambic pentameter! Remember that a sonnet raises a scenario or problem, then gives a different perspective at the end. Where this shift happens depends on the structure you have chosen. Sometimes this shift is indicated by words like ‘but’… or ‘and yet’.... Start your poem! Don’t plan your ideas too much – see where the vocabulary and structure take you. Try to use some imagery or symbolism in your poem. For example, the first words on each list do not need to be literal – despair could be hovering, love could be retreating, mystery could be following. Or whatever you like. Remember – writing a sonnet is not just a game of fitting in the words, the rhythm and the rhyme. That is only a starting point. A sonnet should also come from the soul – it should say something that you want to say. Don’t be afraid to make changes or go in a different direction. A good poem takes work! Spend some time drafting and considering if you have chosen the best words for what you want to achieve. 9