Underneath Chaucer`s Pardoner

advertisement

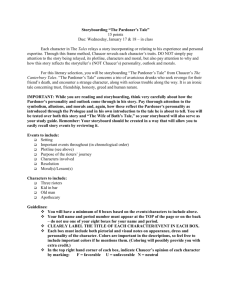

Underneath Chaucer’s Pardoner. Subject: English Literature I Student: Daniela Fernanda Pavero Lecturer: Cecilia Pena Koessler English Department of the I.S.P. Dr. Joaquín V. González 2010 Underneath Chaucer’s Pardoner. The Canterbury Tales, the collection of stories written by the English author Geoffrey Chaucer, is considered to be a portrait of the late medieval England with its social and political upheavals (<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Canterbury_Tales> [Retrieved 30 October 2010]). The use of ‘carnivalesque elements’ (Bisson 1998: 250) all along this frame narrative is a resource Chaucer finds -and skillfully uses- not only to describe but also to criticize the society of his time in a humorous, not offensive way. This essay will focus on one of the pilgrim characters in particular, the Pardoner; and the way in which the father of English literature, through this personage’s portrait, prologue and tale, succeeds in criticizing a powerful as well as corrupt institution developing strategies in order to avoid the possibility of being censured. Chaucer’s England was Catholic England. The great majority of the people were believers. The Church had become rich and extremely powerful, and crying abuses had come into existence. Although Chaucer accepted the religion of his days, he disapproved of those men who entered the service of the church for the purpose of serving their own interests (Bennett 1947: 12). Such is the case of many of the churchmen Chaucer depicts in The Canterbury Tales, men who do not practice what they preach, or even understand what they profess to believe. For one thing, ‘no writer who wished to give a representative picture of England in the fourteenth or fifteenth century could have ignored this portion of [the] material’ (ibid). Anyway, the exposure of that serious flaw in the religion of his time, this attack to the reigning orthodoxies of the moment, could not have been expressed in a direct or aggressive fashion without suffering censorship. Some scholars argue that Carnival reinforces hierarchy, presenting the opportunity for lower classes to mock and laugh at those who dominate them, to liberate their strong bad feelings towards the powerful and rich, and, thus, prevents subdued people from rebelling (Bisson 1998: 259). In this case, far from functioning as an instrument to keep society unchanged, Geoffrey Chaucer is reacting and trying to make others react. He is denouncing the immoral behavior of the members of the church, making their corruption public, and inviting the reader to dispise those hypocrites’ actions, just as he does. If he resorts to the carnivalesque, it is only because he needs to find a way to make his attack less aggressive. His Pardoner is, physically and spiritually, so different from what anyone would expect, so materialistic and disgusting, so carnivalesque, that it is difficult to realize whether Chaucer is being serious. In the General Prologue to the Tales, the Pardoner is introduced and described as a rascal. The reader soon understands that this official of the church is not to be altogether trusted. His job is to sell indulgences from Rome but many of the religious objects he sells are fakes. In spite of the fact that he is a churchman, Chaucer does not devote much to his moral virtues or spiritual life but rather focuses on the character’s physical appearance, his hair, yellow as wax and smooth; his bulging eyes, his effeminate nature and his concern for clothes and fashion. (Chaucer 1951: 37) The writer creates a grotesque figure, offensive and unpleasant to the sight. His physical ugliness is just an exteriorization of his poor spirituality. ‘While clerical culture exalts the spirit, the grotesque celebrates the body: “The essential principle of grotesque realism is degradation, that is, the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract; it is a transfer to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in their indissoluble unity”.’ (Bisson 1998: 250). From the very beginning, Chaucer makes it clear that the Pardoner’s personality and behavior will operate within the realm of festival values. Aspects of the carnivalesque also emerge in the Pardoner’s actions and sayings in the prologue to his tale. Contrary to what one might expect from someone with such a job, he associates himself with the earthly and physical. He celebrates eating and drinking, rejects poverty and his only concern is to get money, wool, cheese and wheat, no matter if it comes from the poorest lad in the village. He seems to be open to the other pilgrims and exposes himself, admitting his telling of mockeries and his own sins, such as avarice (Chaucer 1951: 259). ‘Though the Pardoner preaches against greed, the irony of the character is based in the Pardoner's hypocritical actions. Using his position as an agent of the Roman Catholic Church, he admits extortion of the poor, pocketing of indulgences, and failure to abide by teachings against jealousy, and avarice’ (<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pardoner%27s_Tale> [Retrieved 30 October 2010]). His total disregard for the absolution of sins and fare of the others’ souls also reflect carnival values. Finally, in the Pardoner’s tale, there are some elements related to the carnivalesque as well. He opens his tale talking about sins and excesses: drunkenness, madness, gluttony, gambling… The main characters in his tale are spiritually dead people, sinners, who die out of avarice (Chaucer 1951: 262). Here, a parallelism can be made between the Pardoner himself and the main characters in his tale since they all share many characteristics, such as the lack of moral values. What Chaucer might be suggesting is that this Pardoner, though member of the church, is no less unscrupulous than the three rioters, and, therefore, deserves to have no better luck. To conclude, the concepts described by the Russian critic Bakhtin as typical of Carnival, that it subversion through laughter, parody, the grotesque body, the comic debasement of authority, (<http://books.google.com.ar/books?id= (...)> [Retrieved 30 October 2010]), can all be found in the Pardoner’s portrait, prologue and tale. The inclusion of them in his work is another proof of Geoffrey Chaucer’s skill to give utterance to his views without exposing himself or sounding aggressive. Underneath Chaucer’s Pardoner, there is a clear reference to the abuses and corruption present in the medieval Catholic Church and to the contrast between precept and practice in the lives of men nominally devoted to the advancement of religion (Lounsbury 1892). However, they seem to be so exaggerated and paradoxical, and are told in such a way that they sound as if they could not be real, as if they had been invented just for the sake of laughing… References Bennett, H. S. (1947). Chaucer and the Fifteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Bisson, Lillian (1998). ‘A Zone of Freedom: Carnival as the Emblem of an Age’. Chaucer and the Late Medieval World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Chaucer, Geoffrey (1951). The Canterbury Tales. Nevill Coghill (trans.). London: Penguin Group. Eisenbichler, Konrad. ‘Better be sott Somer than Sage Salamon’. Carnival and the Carnivalesque. [30 Oct. 2010] http://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ftLrm0N_H5EC&printsec=frontcover&dq=% 22Carnival+and+the+carnivalesque%22&source=bl&ots=Ev8IQjFRLT&sig=xwuin d3Y3_rmTHpAgmWG_01lKbg&hl=es&ei=eXjQTMHeGsP88AaJwNGlBg&sa=X &oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f= false Lounsbury, T. R. (1892). Studies in Chaucer. New York: Harper and Brothers. ‘The Canterbury Tales’. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [30 Oct. 2010] <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Canterbury_Tales>. ‘The Pardoner’s Tale’. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [30 October 2010] <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pardoner%27s_Tale>.