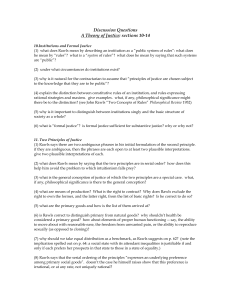

Political Liberalism Essay

advertisement

Political Liberalism: First Essay Wylie Breckenridge Okin suggests that the absence of discussion of justice in families and justice and gender was a major problem in Rawls's A Theory of Justice, and that gender continues to be so in Political Liberalism. Evaluate Okin's argument. Do you agree or disagree? What would a liberal theory of justice have to do in order to do justice to feminist claims about justice? In 'Political Liberalism, Justice and Gender'1 Susan Moller Okin argues that in Political Liberalism2 Rawls fails to adequately deal with the issues of justice in families and justice and gender. In fact, she claims that whereas A Theory of Justice3 had great potential to deal with them, PL is in a considerably worse position to do so. Her main charge is that its greater toleration for a pluralism of reasonable comprehensive doctrines is in serious conflict with the equality of women, so that Rawls is mistaken if he thinks that PL can allow for both. Furthermore, she complains that Rawls leaves it unclear whether or not a political conception of justice can provide for substantive equality between the sexes, rather than merely formal equality which she believes is inadequate when it comes to dealing with justice and gender. In this essay I will present Okin's argument, and then offer a defence of PL against it. Okin's Argument In PL, Rawls's main aim is to rectify what he sees as a flaw in Theory. There he presented the idea of a well-ordered society regulated by justice as fairness - a comprehensive, or at least partially comprehensive, moral doctrine to be endorsed by all citizens. He has since come to think that because of what he calls 'the fact of reasonable pluralism' expecting every citizen in a society to endorse a single moral doctrine is unrealistic and incompatible with achieving political stability in that society. In PL Rawls develops instead a political conception of justice, one that can be endorsed by all reasonable citizens as compatible with their individual comprehensive moral, philosophical and religious doctrines, even if those doctrines are incompatible with each other. Being more tolerant of doctrinal diversity, Rawls hopes that such a conception of justice is both more realistic and stable - it allows reasonable citizens to agree upon a conception of justice without compromising their own deeply-held moral, religious and philosophical convictions. If it is to be endorsed by people who hold a wide range of reasonable comprehensive doctrines, a political conception of justice must be the focus of what Rawls calls 'an overlapping consensus' of those doctrines, and its subject matter must, accordingly, be limited. It is limited to 'the domain of the political', by which he means those political, social, and economic institutions that form the basic structure of society, and how they are organized into a system of social cooperation. The classification of institutions into 1 2 3 Susan Moller Okin, 'Political Liberalism, Justice, and Gender', Ethics 105 (October 1994): 23 - 43, hereafter referred to as Okin. John Rawls, Political Liberalism, New York: Columbia University Press, 1996, hereafter referred to as PL. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971, hereafter referred to as Theory. -1- political and nonpolitical, then, is an important aspect of PL because it is the means for judging whether or not a given institution is to be regulated by the principles of justice. Okin argues that PL's greater religious toleration immediately causes it an internal problem. She points out that at least some religious doctrines include the belief that there is a natural hierarchy between the sexes, with some being "highly patriarchal, [and] advocate and practice the dependency and submissiveness of women" (Okin, p. 31). And she points out that Rawls seems to think that such views are to be tolerated, citing him as saying that citizens may hold views such as that there is a fixed natural order or a "hierarchy justified by religious or aristocratic values" (PL, p. 15). To tolerate the moral, religious and philosophical pluralism as Rawls wants to in PL is to tolerate, Okin argues, the belief that the sexes are not equal. But this raises a problem for a feature of PL that Rawls calls 'congruence' - the agreement (or at least absence of conflict) between a person's political and nonpolitical values - an important ingredient for the achievement of stability. Okin asks how it could be possible for someone to hold that every citizen is free and equal (a political value required by all reasonable citizens), and also to hold that there is a natural hierarchy between the sexes (a nonpolitical value that Rawls seems to allow). It seems that by requiring its reasonable citizens to be able to achieve congruence, PL automatically excludes them from holding certain comprehensive doctrines, thus compromising the toleration upon which it is based. Okin's further charges against PL centre upon the classification of the family as a political or nonpolitical institution. She points out that Rawls is unclear on the matter. On the one hand he says: "the political constitution, the legally recognized forms of property, and the organization of the economy, and the nature of the family, all belong to the basic structure" (PL, p. 258). Furthermore, he says: "the institutions of the basic structure have deep and long-term social effects and in fundamental ways shape citizens' character and aims, the kinds of persons they are and aspire to be" (p. 68), something that is certainly true, Okin suggests, of the family. If it belongs to the basic structure, as Rawls seems to be implying here, then the family is a political institution and thus subject to the principles of justice. In fact, Rawls also says: "the individual members of families [need protection] from other family members (wives from their husbands, children from their parents)" (p. 221, n. 8), and such protection can only be provided if the family falls within the domain of the political. On the other hand, however, he says: "The political is distinct … from the personal and the familial, which are affectional … in ways the political is not" (p. 137), implying, in apparent contradiction to the previous quotes, that the family is not political. Okin suggests that what she describes as "Rawls's reluctance to apply consistently his standards of justice to families" (Okin, p. 27) indicates that he realizes just how much of a problem the family is for a political conception of justice. She believes that "the family is a social institution that defies the political/nonpolitical dichotomy" (loc. cit.). If it is classified as political, then family life is open to public scrutiny and regulation by the principles of justice. But since family values are deeply rooted in people's comprehensive moral, religious and philosophical doctrines, any regulation of them by state power goes against the toleration of reasonable pluralism that is fundamental to PL. In short, thinking of the family as a political institution seems to be incompatible with the toleration of reasonable pluralism. If it is classified as nonpolitical, on the other hand, then that will create another internal problem for PL. It has to do with the development of what Rawls calls 'the political virtues' - reasonableness, a sense of -2- fairness, a spirit of compromise, toleration, mutual respect, and a sense of civility. Rawls stresses throughout PL how important it is for the stability of a well-ordered society that its citizens develop these virtues. But Okin argues that if the family is classified as nonpolitical, along with the various religious and associational institutions, then it cannot be guaranteed that citizens will develop these virtues. If Rawls allows that nonpolitical institutions can advocate the view that the sexes are not equal, then, Okin believes, it cannot be guaranteed that in such institutions the political virtues can be learned. If the family is one such institution, and if, as Okin claims, the family is where children spend the greatest part of their most morally-formative years, then it cannot be guaranteed that children will grow up to learn the political virtues at all. In short, it seems that Rawls cannot allow for the toleration of reasonable pluralism in a wellordered society and also expect that its citizens develop the political virtues, as they must if stability is to be achieved. Okin goes on to argue that if PL does not require the principles of justice to apply to the family, then it does not provide a satisfactory solution to the problem of gender inequality. She says: "No matter how formally equal women are, so long as the social structures that depend upon a gendered division of labor are still in place … women will remain systematically disadvantaged" (Okin, p. 42). As evidence for the claim that merely formal equality is insufficient she cites an analogous case: "[formal legal equality] has proved vastly insufficient for the achievement of anything like 'fair equality of opportunity' for black Americans" (p. 39). The gendered social structure that she particularly has in mind is the family. She says: "women continue to bear disproportionate responsibility for domestic work, raising children, and caring for the sick and elderly", with this work being "undervalued, and unpaid or underpaid" (p. 42), supporting her case with statistical data. She argues that if gender inequality can only be truly abolished once the social structures that maintain it are broken down, and if unjust family life is one such social structure, then true gender equality can only be achieved by the political system advocated in PL if it allows that families be subject to the principles of justice - that is, if it takes the family to be political. So Rawls's failure to clearly deal with the issue of justice in families amounts to a failure to deal with the issue of justice and gender. In fact, Okin suggests that Rawls leaves it unclear whether or not he believes that more than formal equality can be provided by PL. His most explicit treatment is a single statement in the introduction: "The same equality of the Declaration of Independence which Lincoln invoked to condemn slavery can be invoked to condemn the inequality and oppression of women" (PL, xxxi). Okin claims that this is ambiguous - that it could be taken as saying: "that all that women need in order to be treated justly is equal basic rights with men and the formal freedom to choose a traditionally female or a less nongendered life" (Okin, p. 43); or as advocating: "an anticaste solution for women to undo the long centuries of injustice" (loc. cit.). Okin argues that only if PL can provide for substantive equality, as advocated by the second interpretation, can it be thought to adequately treat the issue of gender equality. A Defence Now I want to offer a defence of PL against these charges of Okin. I do not want to argue that Rawls makes his position on justice and the family clear in PL, because he does indeed seem, as Okin has pointed out, to make contradictory statements. Nor do I want to argue that he can count the family as political without compromising the greater toleration fundamental to PL. That may be the case, but it is not my concern here. What -3- I want to argue is that PL can regard the family as nonpolitical and tolerate a pluralism of comprehensive doctrines, including ones that hold hierarchical views, without facing the two apparent internal problems that Okin suggests it would, and without closing off the possibility of achieving substantive equality between the sexes. First, the problem of congruence. The question Okin raises is this: how could it be possible for someone to hold that every citizen is free and equal and also to hold that there is a natural hierarchy among them - to hold, for example, that men have a natural right to power over women? I think it's important here to consider closely what Rawls means by 'free and equal'. He says: "The basic idea is that in virtue of their two moral powers (a capacity for a sense of justice and for a conception of the good) and the powers of reason … persons are free. Their having these powers to the requisite minimum degree to be fully cooperating members of society makes persons equal" (PL, p. 19). I understand Rawls to be saying, here, that people are to be thought of as equal in the sense that each has the intellectual capacity to be a fully cooperating member of society. It requires any reasonable man to think of every woman as equally capable as he is of being a fully cooperating citizen. It does not require him to think of them as equal in any wider sense. In particular, it does not require him to think of them as having completely equal intellectual capacities, or physical capacities, or the equal ability to hold positions of responsibility. It just requires that he regards them as equally capable of participating in systems of cooperation - to be able to put forward reasonable points of view and to expect them to be reasonably considered. It seems plausible to me that a man might be prepared to fully cooperate with men and women alike, and yet believe that women should perform certain tasks rather than men, because, for instance, of their different physical capacities. In one sense he would not be regarding women as his equals. But in Rawls's sense, and that is the one at issue here, he would. Of course, if he refused to debate the matter with women or even forced them to perform those tasks, then he would no longer be regarding them as fully cooperating members of society, and so would no longer be regarding them as equal in Rawls's sense either. But Okin's charge is that by holding the view that men and women are unequal in a broader sense he must also hold the view that they are unequal in the narrower Rawlsian sense, and that doesn't seem to me to be right. Second, the problem of the development of the political virtues. Okin's concern is that the family is not a reliable school of justice. In fact, she is concerned that many contemporary families are poor schools of justice. She draws upon two pieces of recent research. The first suggests that unequal divisions of work between mothers and fathers are reflected - even magnified - in unequal divisions of work assumed by the children. She asks: "Is such a family environment a good place to learn to be just and to treat each other as equals, to acquire … the political virtues … ? Or is it a place where people absorb the message that they have different entitlements and responsibilities, based on a morally irrelevant contingency - their sex?" (Okin p. 36). Clearly she thinks the latter. But I think it would be a mistake to draw any such conclusion, because of what Okin herself points out: "Unfortunately, those doing the study did not interview the adolescents (or their parents) about their perceptions of the fairness or unfairness of the situation" (p. 36). It seems possible to me that a family with an unequal division of labour between the males and females, even if that division is substantial, could still be an environment in which its members are learning the principles of justice. Just because a family situation is what we, looking from outside, might think of as unjust, it does not follow that the members of that family regard it as so, nor, in particular, that it was -4- arrived at by an unjust procedure. It may well be the case that the family sat down and entered into a fully rational and reasonable discussion of how the labour was to be divided, with the parents demonstrating to their children how to exercise a sense of fairness and compromise, toleration, mutual respect, and civility - all of the political virtues. It is equally possible that a family whose division of labour would be regarded by we external observers as just is actually a poor environment for learning these virtues. The parents may, for example, have simply imposed an equal distribution of labour on their children, without discussing why, nor considering whether or not one child may actually want to do more work than the others. Political virtue, as I understand it, is the ability to enter into a form of social cooperation, and not the holding of certain beliefs about how society should be. To decide whether or not a given family is an environment in which children can learn political virtue, then, we must look to whether or not it fosters this ability to cooperate, and not to whether or not it promotes certain beliefs about the structure of society. The second piece of research that Okin cites finds that the wives and daughters in Druze Arab families accept as inevitable the power of the male family head over many of their activities and decisions, and, moreover, regard it as unjust. She describes this as "the learned acceptance of injustice, enforced by male power", and urges: "Surely such hierarchical early learning environments are not suitable training grounds for just citizens of either sex" (Okin, p. 37). If the research is right, then it is difficult not to agree with Okin - such family situations cannot be trusted to encourage the development of political virtue, and so they threaten to undermine the stability of Rawls's wellordered society. Okin argues that if the family is placed outside the political arena, as it must be if PL is to be as tolerant as Rawls wants, then the state cannot intervene to ensure that the children in these families grow up in an environment in which they can develop the political virtues. Rawls would say, and I think that Okin would agree, that the men in these families are, by his definition, unreasonable. This is significant, because early in PL he says: "Of course, a society may also contain unreasonable and irrational, and even mad, comprehensive doctrines. In their case the problem is to contain them so that they do not undermine the unity and justice of society" (PL, xviii xix). I think it would be agreed that the practices of these unreasonable men do threaten to undermine the justice of society, by upsetting the requirement, for example, that all citizens be able to develop the political virtues, and thus upsetting the ability of society to obtain stability. So it seems to me that in the case of families like those of the Druze Arabs, the state is indeed licensed to intervene in the family situation, even though the family institution in general is nonpolitical and, therefore, off limits. I think Okin agrees with this, but her concern is that if the practices of these families are judged as unreasonable then so too must the practices of the many religions that preach sex discrimination, and therefore that if the former are not to be tolerated then neither are the latter, which calls in question the ability of a political conception of justice to be as tolerant as Rawls believes. I think that she misses two important points here. Firstly, to be reasonable, if I understand the term correctly, is to be prepared to engage in a fair system of cooperation with others regarded as free and equal. But 'equal', here, means equal in Rawls's sense, a sense that I argued above should not be taken too broadly. It seems to me that a religion can regard men and women as unequal in one sense - for example, by stipulating that only men can hold certain offices - and yet regard them as equal in Rawls's sense - by being prepared to debate with women the reasons for this stipulation, treating them as equally able as men to present reasonable points of view, -5- and reasonably considering those points of view. If I am right in this, then it does not follow that any religion that preaches sex discrimination must be unreasonable, but can only be judged so by duly considering its wider operations. Secondly, even if a religion was found to be unreasonable it may not threaten to undermine the unity and justice of society, which is Rawls's main concern, and so it may not need to be deemed intolerable. If a particular unreasonable religion (i) had compulsory membership, and (ii) was the main (if not only) source of political education of its members, then it would, like the Druze Arab families, have to be regarded as a threat to the unity and justice of society, and therefore it would have to be regarded as intolerable. But without such conditions then I can see no reason why it should not be accommodated by a reasonable pluralistic society. Finally, the matter of formal versus substantive gender equality. I do not want to disagree with Okin that Rawls is unclear about whether PL can promote the latter - he certainly seems to be. But I do want to disagree with her suggestion that the greater toleration of PL takes away its ability to ensure substantive equality between the sexes. By substantive equality she means the breaking down of the social structures that hinder formal equality from becoming real equality. In particular, she means the breaking down of gender inequality in families - such as the distribution of work, power and opportunity. Okin is concerned that if the family is placed outside the political arena, as it must be if PL is to be as tolerant as Rawls wants, then the state cannot intervene into family life to ensure that gender inequality is stopped. My defence of PL here takes a similar line to the one above. PL licenses the state to intervene into families in which the exercise of unreasonable comprehensive doctrines threatens to undermine the unity and justice of society, and that, as I have argued, is the case in families whose female members believe that they are unjustly expected to do an unfair share of work, or are unjustly restricted in the responsibilities that they can bear. In those cases, the state can step in to ensure that such structures are broken down, without compromising its toleration of reasonable pluralism. I do not believe, however, that it is automatically so licensed in every case of a family whose workloads are unequally shared, because it is possible that such families are regulated by reasonable comprehensive doctrines and that they are actually good schools of political virtue. In those cases I agree with Okin. But I do not think they pose any barrier to substantive equality between the sexes. Although the members of these families accept a structure that we from outside might regard as unjust, it is because they themselves do not regard them as so, and not because they have learned to accept injustice. If, and when, they come to think that their family situation is unjust, then they will, as rational and reasonable citizens who have developed a sufficient sense of justice within their family, be able to adjust accordingly. If they cannot, then there must be some unreasonable force within the family, and because of the danger this poses to the unity and justice of society, the state can intervene. Conclusion Okin's charge against PL is that if Rawls expects a political conception of justice to allow a pluralism of comprehensive moral, religious and philosophical doctrines to coexist in a well-ordered society, then (i) he cannot expect all of its citizens to achieve congruence between their political and nonpolitical values, and so he cannot expect that society to achieve stability in the way that he describes, (ii) he cannot expect all of its citizens to fully acquire political virtue, and so, again, he cannot expect stability to be -6- achieved, and (iii) he cannot expect that substantive gender equality can be achieved in that society, and so he cannot expect a political conception of justice to be capable of adequately dealing with the pressing contemporary issue of justice and gender. I have argued that (i) if we distinguish the meaning of 'equal' as we tend to use it when discussing gender equality from the narrower meaning I think that Rawls intends in PL, (ii) if we understand being reasonable and being politically virtuous as the ability to act in a certain way rather than as the possession of a particular set of beliefs about how society should be structured (i.e. a particular conception of the good), and (iii) if we take Rawls seriously in his claim that any unreasonable comprehensive doctrine that threatens to undermine the unity and justice of society ought to be contained, then, on all three counts, he can. -7-