Introduction

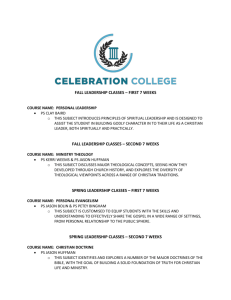

advertisement

Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 1 Don Sik Kim Discovering and Redeveloping Cosmic Pneumatology Don Sik Kim, PhD Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary Introduction Because religions, including Christianity, are not incidentally imagistic but centrally and necessarily so, theology must also be an affair of the imagination.1 - Sallie McFague Nature, the world, has no value, no interest for Christians. The Christian thinks of himself and the salvation of his soul.2 - Ludwig Feuerbach The urgent commitment to the protection and maintenance of ecological health and justice required of the human community has brought Christian theology to an unexpected connection between ecology and ecumenism, both words that denote the taking care of house, oikos. Ecumenism, which is not committed to the ecological health of our planet will be discredited and rejected by humanity as a movement of narrow tribal interest. The Christian faith must be expressed in terms of the webbed relationship between the life of the planet and the life of all living beings. The ekklesia can live and remain meaningful if the kosmos stays healthy. The Holy Spirit ecclesiastically understood must illuminate the Holy Spirit ecologically understood to envision the ecological health and justice of the oikos. What do these thoughts mean for the future of greening the doctrine of creation? My deep concern for both ecological concern and social justice is related to the anthropomorphic and masculine theistic understanding of God in Christianity. I see a deep connection for the integration of ecology and pneumatology is the new 1 Sallie McFague, Models of God: Theology for an Ecological, Nuclear Age (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987), 38. 2 Ludwig Feuerbach, The Essence of Christianity (New York: Harper and Row, 1957), 287. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 2 Don Sik Kim understanding of the Spirit in the world. As many scholars poignantly described that Protestant pneumatology in particular was in caught in the perceived in dichotomy between the Divine Spirit and the human spirit, “the transcendence of the Spirit and the Spirit’s immanence” (Moltmann, 1992, 5-8).3 Spirit language is particularly useful in evoking the presence of God in ways that are beyond the human. Indeed, pneumatology must recognize the Spirit’s work beyond the boundaries of the church and human beings to overcome the contemporary penchant for experience beyond desire for individual fulfillment and temporal satisfaction. The Spirit seemed to be an invisible energy and the power and a kind of transcendent-immanent medium which connected people to God and the world. God as Spirit is not identical with the material world or any part of it, but also never separable from it. In Christian theology, however, the concept of the Spirit of God has been primarily viewed from an anthropomorphic imagery, which God’s relation to humans is the central focus of the theological enterprise. Human beings are not only elevated above other beings, but also Western individualism benefits each person’s relationship with other beings as if each human being belongs to a different category of existence. Thus, any impersonal or non-personal understanding of the Spirit has been devalued in Christian traditions. What is needed today is a new paradigm of the Spirit in the context of globalization and post-modernism. Such a new paradigm must begin by giving substance to the meaning of the word “spirit.” Under the influence of modern rationalism and materialism, the category of spirit underwent a sustained assault, such that the term became meaningless to many in Western societies. In such a climate, the biblical term 3 Jurgen Moltmann, The Church in the Power of the Spirit: A Contribution to Messianic Ecclesiology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992), 5-8. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 3 Don Sik Kim “Holy Spirit” is divested of its profound scriptural meanings; it has lost its cosmic dimensions, and its connection with God the Creator. The problematic of “spirit” is complex biblically but that complexity is the heart of the matter. There is a strong distinction but no sharp line between the Spirit that is God, known finally as the Holy Spirit, and the spirits of creatures, including humans. That distinction, however, must not be interpreted dualistically, nor monistically flattened. 1. The Spirit in the Scripture – ruach and pneuma The word “Spirit” is originally derived in the Bible from the Hebrew word ruach, which means “wind,” “air,” “breath,” or “spirit,” and came to mean divine power, including the power of life itself. However, in the Septuagint, the Greek word pneuma is almost always used as a translation for ruach, and so takes on a very similar range of meanings. The early Christian writers were therefore able to bring together all the varied meanings of ruach to inform their understanding of the Spirit in life. The Spirit of God in the ancient Hebrew Scriptures is a way of talking about the presence and action of the one God of Jewish monotheism. This Spirit was not understood in personal or trinitarian terms. The Bible puts before us the image of the Spirit as the breath of God that enlivens in beings and things in the creation. The Hebrew word ruach occurs at the beginning of the Scriptures in Genesis 1:2, when the Spirit or “wind” of God is described as hovering over the face of the waters at creation. “Wind” is the most common meaning of ruach, because it is invisible and was understood to be caused directly by the divine power of God. The breath of God is both creative of life and destructive in the Bible (Gen. 6:3; 6:17; 7:22). In Genesis 2:7 God breathes into Adam to constitute him as a “living being.” Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 4 Don Sik Kim Though the word used here is neshama, this is a synonym for ruach. Ruach is often used in the sense of “breath of life” in the Bible. In a vision of Ezekiel, for example, the dry bones in the valley come to life as a result of God’s ruach (37:3-10). The two terms appear in parallel in Isaiah 42:5, where the Lord “gives breath (neshama) to the people upon the earth and spirit (ruach) to those who walk in the earth.” Job also sums this up: “The spirit (ruach) of God has made me, and the breath (neshama) of the Almighty gives me life” (Job 33:4). As we have seen, the root meaning of ruach leads to an association of the imaginary of wind, breath and air with God’s Spirit. This association continues in the New Testament with the word pneuma. The Spirit blows where it wills (John 3:8), and the Spirit comes like a wind at Pentecost (Acts 2:2). The meaning of ruach is also reflected in the use of pneuma to refer to the breath of life in the New Testament (2 Cor. 3:6). For example, it is clearly described that when Jesus breathes the Spirit into the disciples (John 20:19-23). The Hebrew word ruach and the Greek pneuma carried many different connotations of the Spirit in creation and life in the Scriptures: word, water, fire, power, new life. Although biblical scholars agree that there is no passage in the New Testament in which the Spirit of God appears as working in the entire creation, both the role of the Spirit in bestowing life and the Spirit’s activity in creation are beyond dispute in the Old Testament. However, biblically the Spirit of God cannot be reduced to the power of the human spirit or to the power within the Christian community, although it has been done in traditional Christian theology, specifically in the development of the Trinity and the Holy Spirit. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 5 Don Sik Kim In this way, Paul Tillich’s work in his systematic theology provided a foundation for the correlation of the Spirit and life, which he understands life to be the process of the “actualization of potential being,” that is, the unity of the essence and existence of being, its power and meaning in the Spirit.4 For Tillich, “spirit” (with a lower-case “s”) provides the necessary symbolic material to understand the religious symbols “divine Spirit” or “Spiritual Presence.” The relation between the Spirit and spirit is that “the divine Spirit breaks into the human spirit” and “derives the human spirit out of itself.”5 Tillich’s association of Spirit with spirit in the sense of the human dimension of life led him to connect Spirit with human creativity in culture rather than with biological life. However, he recognized the “multidimensional unity” of life and the influence of the Spiritual Presence on the ambiguities of life. This is he saw most clearly in healing, which he described as bringing “self-integration of the centered life.”6 Also, Jurgen Moltmann poignantly described that Protestant pneumatology was in caught in the perceived in dichotomy between the Divine Spirit and the human spirit, “the transcendence of the Spirit and the Spirit’s immanence.”7 Therefore, the question of the scope and nature of the Holy Spirit’s presence and activity in the world has implications across the whole range of theological thought. 2. Karl Barth’s Construction of God-World Relationship 4 Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol. I (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1951), 54-55. Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol. III (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1963), 111-12. 6 Ibid., 275-77. 7 Jurgen Moltmann, The Church in the Power of the Spirit: A Contribution to Messianic Ecclesiology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992), 5-8. 5 Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 6 Don Sik Kim An ecological theology needs Spirit language that embraces and includes the nonhuman. It needs more than parent-child images. Language about God is an important issue for this study and with feminist theologians I believe that in order to speak rightly about God who embrace and transcends both human and nonhuman worlds, we need to propose a theology of reciprocal relations between God and the world. In this section, I seek an attempt to draw together and synthesize Barth’s thought on a theology of relations. The analogia relationis in Barth’s work can be termed as a “relational ontology” because it considers the ontological relationship of two different beings, namely God and human creature. Barth asserts that the whole of humankind is dependent upon and related to the being of God in one way or another ontologically. Furthermore, in Barth’s theology of creation, creation has a sacramental quality. For Barth, the whole of creation is like a sacrament ceaselessly conveying the loving grace of God. While much attention has been given to Barth’s use of analogy, I want first to explore the nature of the relationships which Barth indicates are analogous. The term analogia relationis (analogy of relations) does not occur until Barth considers the Christological grounding for anthropology. This makes perfect sense in that there would be no sense of speaking of some kind of comparison until the second term of comparison is brought to the foreground, in this case human relations to God and then with each other. However, since Barth ultimately sees human existence to be grounded in the triune life of God, a detailed study of the nature of the triune relationships is required for us to recognize in what way the relationships in the spheres of Christology, anthropology and special ethics are indeed analogous. Before we move on to the trinitarian relations, we should note an important way Barth comprehends “relations.” In his discussion of the analogia relationis, Barth, without much explanation, expounds his understanding of the nature of relationships using two mutually related terms: “form” or “structure” and “material content” or “action.” For Barth, relations can be grasped in terms of form and content, or structure and action. These terms cannot be separated from one another. Each Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 7 Don Sik Kim interprets the other. The basis for this categorization is not any commitment to Platonism or Idealism, even if this terminology is found there, too. These terms reflect Barth’s understandings that the God revealed in the Word is united in being and action.8 The Word concretely and particularly reveals God as united in being and act. Barth interprets form as pointing to the being/character of the one in a relation and interprets the content, even more unusually, as the action which corresponds to the being in relation. Through Jesus Christ, God is true to his being — true to his character, in his acts of creation, reconciliation and redemption. His actions are actually revelatory of who God is. The form and content of his relation with God and with us are in complete correspondence. So, for Barth, all relations can be comprehended in terms of the theologically defined categories of form and content. The trinitarian, Christological and human relations can be said analogical in the sense that each in its own way involves inseparably act and being, content and form. This discussion leads to the point of considering again the correspondence of the relations. How can we correlate the intra-trinitarian relations with Jesus’ relations with God and others and our relations with God and others? Barth begins to make his most explicit answer at this point. Indeed, Barth indicates that he was familiar with the term analogia relationis first used by Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his Creation and Fall.9 It was Bonhoeffer who also suggested the contrast between analogia relationis and analogia entis. Barth’s usage seems largely to be in agreement with Bonhoeffer’s as an interpretation of the imago Dei being a purposive relation given by God and not a capacity, possibility or a structure of [hu]man’s being. This term is especially developed much earlier in Church Dogmatics, II/1, 28, “The Being of God as the One Who Loves in Freedom.” 8 9 Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, III/1, 194ff. See Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Creation and Fall (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1971), 38-39. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 8 Don Sik Kim The analogia relationis does not serve as a methodology by which to derive theological truths. Rather, “analogy” is, for Barth, an ontological term. It is an explication of the person and work of Jesus Christ as the Elect of God revealing God himself, as a saving of humanity that is not external to humanity or God. It designates the reality of “Immanuel” and keeps this name from disintegrating into a metaphor. It guards the way to real relationship now and in eternity which involves the being of God and of humanity, which involves their very existence. It means that God himself is what God does and so is freely sovereign and sovereignly free in God’s electing love. It means that God remains even while being in actual communion with God himself. It connotes that God is not arbitrary in God’s election but free in himself for humankind. It denotes that God is the one who saves and is none other than humanity’s salvation. Human is actually created according to God’s image, Jesus. And all this without God or humanity ceasing to be what they are or changing into something alien which they are not. This is, of course, why Barth must insist on no analogia entis in which case one could mistakenly deduce the interchangeability of humanity and divinity. Ultimately, Barth avoided speaking of being/ontology in the abstract because he believed this would misrepresent the relational nature of God’s and human existence. Relations constitute being. So there is no being without being in relation in the triune life and in human life. Barth consequently focused on the relations. Alan Torrance points out, however, that this does not resolve all the issues. There are still individuated beings being in relationship. And if the relations are properly as analogous (analogia relationis) and these relations constitute being, then there has to be some sort of analogy of being, analogia entis. Barth himself allowed a qualified acceptance of the analogia entis, namely, by way of the analogia fidei, the analogy of faith, and in Jesus Christ. We may speak of an analogia entis not by way of cause Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 9 Don Sik Kim according to creation, but by way of covenant by way of redemption.10 The former seems to represent the Thomistic way of rendering the analogia entis, and this Barth rejects.11 Here, Barth is clear that humanity, which is to say personhood, is essentially constituted by its being in relationship with other persons. These inner-human relations are not arbitrary or accidental but necessary for human existence as human. This is a secondary determination of humanity compared to its relationship with God, but just as essential. This secondary determination of humankind is parallel to Jesus’ own secondary determination of his existence by our humanity. Our being is determined by our vertical relation with God. But, because it is so determined, it is on that basis to be conditioned by the horizontal relationships as Jesus was both from, to and with and so for God so He is from, to, with and for humankind. Barth brings together the similarities of all four relationships: intra-trinitarian, Jesus to God, Jesus to others, and person to person. Barth summarizes this relation of the images most explicitly in a response to a question concerning how human is the image of God transcribed in his Table Talk. Image has a double meaning: God lives in togetherness within Himself [the Original], then God lives in togetherness with human [first image] then human beings live in togetherness with one another [a second image].12 This defines the relationship between the two relationships. There is an original intratrinitarian relation of Father, Son and Spirit; the God-God relationship. There is a 10 Karl Barth, CD, II/1, 82. Analogia entis means an “analogy of being” in a general sense. The concept can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophical thinking. In Christianity, it was Thomas Aquinas in whose work the teaching of the analogia entis reached its peak. Aquinas’ teaching of the analogia entis was based on the concept that every cause produces only the effect that resembles it. In Aquinas’ thought God is seen as the primary and per se cause and as such whatever God produces might resemble Him in one way or another. Hence, there is a kind of similarity in the being of God and man. On this ground the knowability of God by human reason was stressed. However, Aquinas taught that the similarity between God and man is not univocal but equivocal in essence and nature. 11 John D. Godsey, ed. Karl Barth’s Table Talk (London & Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1962), 57 (Hereafter, Table Talk). 12 Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 10 Don Sik Kim corresponding relationship of human to God and human to human in Jesus which is the first image of God, of God in triune relationship. The ontological relation between the being of God and that of the creature is highlighted in his application of the concept of an analogia relationis. In Barth’s work, the term analogia fidei and analogia relationis are used interchangeably and as such it is impossible to make a clear distinction between the two. Jung Young Lee, however, has made distinction between them from the context in which they are used in the following way: The term analogia fidei presupposes epistemology because it is used in the context of epistemological question, that is, the knowability of God (especially in CD II/1). On the other hand, the term analogia relationis presupposes ontology because it is used in the context of ontic relation, that is, God’s relation to the imago dei and creation (especially in CD III/1).13 In fact, his application of an analogia relationis indicates that the question of beings becomes more and more a serious subject for Barth. It is in his use of analogia relationis that the dependence of the creature upon God contingently is brought to light. The hallmark of his dialectical method is that there is an infinite qualitative distinction between God and human, heaven and earth, eternity and time, and revealed and natural theology. As such this infinite qualitative distinction appears to create a gap which theoretically makes it difficult for any attempt to bridge the gap between God and the creature ontologically. This being the case he needed a new method to convey effectively his idea of the ontological relation between God and the creature. Hence, he was forced to turn from the dialectical method to the concept of analogy. 4. East Asian Construction of God-World Relationship 13 See Jung Young Lee, op. Cit., 138. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 11 Don Sik Kim The Neo-Confucian model of the world, “a decidely psycho-physical structure” in the Jungian sense,14 is characterized by Joseph Needham as “an ordered harmony of wills without an ordainer.”15 What Needham describes as the organismic Neo-Confucian cosmos consists of dynamic energy fields rather than static matter-like entities. Indeed, the dichotomy of spirit and matter is not at all applicable to this psycho-physical structure. The most basic stuff that makes the cosmos is neither solely spiritual nor material but both. As Schwartz points out, “ch’i comes to embrace properties which we would call psychic, emotional, spiritual, numinous, and even ‘mystical.’”16 It is a vital force. This vital force (ch’i) must not be conceived of either as disembodied spirit or as pure matter. Ch’i, which is being something that constitutes every being or thing and underlies every phenomenon in the world, embraces both the spiritual and material realms. Wing-tsit Chan cautiously notes that the distinction between energy and matter is not made in Chinese philosophy, for this basic stuff, ch’i, as “matter-energy,” rendering by H. H. Dubs, is essentially sound but awkward and lacks an adjective form.17 Although Wing-tsit Chan translates ch’i as “material force,” he cautions that since ch’i originally “denotes the psycho-physical power associated with blood and breath,” it should be rendered as “vital force” or “vital power.”18 See Richard Wilhelm, Jung’s Foreword to the I Ching (Book of Changes), trans by Cary F. Baynes, Vol. 19 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), xxiv. 14 15 See Joseph Needham and Wang Ling, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 287. Needham’s full statement reads as follows: “It was an ordered harmony of wills without an ordainer; it was like the spontaneous yet ordered, in the sense of patterned, movements of dancers in a country dance of figures, none of whom are bound by law to do what they do, nor yet pushed by others coming behind, but cooperate in a voluntary harmony of wills.” 16 Benjamin I. Schwartz, The World of Thought in Ancient China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 181. 17 Wing-tsit Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, 784. 18 Ibid, 784. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 12 Don Sik Kim The term ch’i, in this respect, implies that the underlying East Asian metaphysical assumption is significantly different from the Cartesian dichotomy between spirit and matter. Apparently, all modalities of being, from rock to heaven, are integral parts of a continuum which is often referred to as the “great transformation” (ta-hua).19 Ch’i as “psycho-physical-spiritual stuff” is everywhere. It suffuses even the “Great Void” (t’aihsu) which is the source of all beings.20 The continuous presence of ch’i in all modalities of being makes everything flow together as the unfolding of a single process. In other words, one advantage of rendering ch’i as “vital force,” is its emphasis on the life process. To the Neo-Confucian thinkers, nature is vital force (ch’i) in display. The eternal flow of nature is characterized by the concord and convergence of numerous streams of vital force (ch’i). Ch’i is characterized to describe the cosmological and ontological process of the world, that is, the world is filled with ch’i and is explained with the result of the self-transformation or the alteration of ch’i. It is in this sense that organismic process is considered harmonious. Chang Tsai defined in his metaphysical treatise, “Correcting Youthful Ignorance,” the cosmos as the “Great Harmony.” The Great Harmony is called Tao. It embraces the nature which underlies all counter processes of floating and sinking, rising and falling, and motion and rest. It is the origin of the process of fusion and intermingling, of overcoming and being overcome, and of expansion and contraction. At the commencement, these processes are incipient, subtle, obscure, easy, and simple, but at the end they are extensive, great, strong and firm. It is ch’ien (“heaven”) that begins with the knowledge of Change, and k’un (“earth”) that models after simplicity. That which is dispersed, differentiated, and discernible in form becomes ch’i, and that which is pure, penetrating, and not discernible in form becomes spirit. Unless the whole universe is in the process of fusion and intermingling like fleeting forces moving in all directions, it may not be called “Great Harmony.”21 19 See Ibid, 264. 20 Ibid, 501. See Chang Tsai’s “Correcting Youthful Ignorance.” 21 Wing-tsit Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, 500-501. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 13 Don Sik Kim In his vision, nature itself is the result of the fusion and intermingling of the vital forces (ch’i) that assume tangible forms. This dynamism of nature is what is called ch’i-hua (transformation of ch’i) in Chang Tsai’s view. Mountains, rocks, rivers, animals, and human beings are all modalities of energy-matter, symbolizing that the creative transformation of the vital force (ch’i) is forever present. In this respect, Chang Tsai further denotes the concept of ch’i as follows: Ch’i moves and flows in all directions and in all manners. Its two elements [yin and yang] unite and give rise to the concrete. Thus the multiplicity of things and human beings is produced. In their ceaseless successions the two elements of yin and yang constitute the great principles of the universe.22 The idea of the moving power of ch’i indicates that harmony will be attained through spontaneity. The opening lines in Chang Tsai’s Western Inscription describe his ontological view of the human. Heaven (t’ien) is my father and earth (k’un) is my mother, and even such a small creature as I find an intimate place in their midst. Therefore, that which fills the universe I regard as my body and that which directs the universe I regard as my nature. All people are my brothers and sisters, and all things are my companions.23 Forming one body with the universe can literally mean that since all modalities of being are made of ch’i, human life is a part of a continuous flow of ch’i that constitutes the cosmic process. Human beings are thus organically connected with rocks, trees, and animals. The proper way of looking at rocks, for Chang Tsai, is to see them as not static objects but dynamic process with their particular configuration of the energy-matter. Despite the principle of differentiation, for him, all modalities of being are organically connected to one another in terms of ch’i. The uniqueness of human being cannot be explained in terms of a preconceived design by a creator. Human beings, like all other beings in the universe, are the results of 22 Ibid, 505. In this translation, ch’i is rendered “material force.” 23 Ibid., 497. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 14 Don Sik Kim the integration of the two basic vital forces of yin and yang. This idea of forming one body with the universe is predicated on the assumption that all modalities of being are made of ch’i, all things cosmologically and ontologically share the same consanguinity with human beings and are thus companions of human beings. It is in this metaphysical sense, according to Chang Tsai, that “all things are my companions.” This literal meaning of forming one body with the universe must be augmented by a metaphorical reading of the same text. It is true that the body clearly conveys the sense of ch’i as the blood and breath of the vital force that underlies all beings. According to Wang Fu-chih, unless human beings see to it that the Mandate of Heaven (T’ien-ming) is fully realized in our nature, we may not live up to the expectation that “all things are complete in us.”24 In the metaphorical sense, then, forming one body with the universe requires continuous effort to grow and to refine oneself. By nature is meant the principle of growth. As one daily grows, one daily achieves completion. Thus by the Mandate of Heaven is not meant that heaven gives the decree (ming; mandate) only at the moment of one’s birth....In the production of things by heaven, the process of transformation never ceases.25 To act naturally with letting things take their own course means, in Neo-Confucian terminology, to follow the “heavenly principle” (t’ien-li) without being overcome by “selfish desires” (ssu-yu). As Chang Tsai described, a human is endowed with virtuous qualities, but is also born with the ch’i which is potentially either good or bad. “Whether or not wealth and nobility can be obtained, depends upon heaven. As to the way of virtue (tao te), he who seeks for it can never fail to obtain it” (6.112). The ‘Physical Nature’ in its original state is morally neither good nor bad, but it has become degraded from the ‘Heavenly Nature’ after having come into contact with other objects, human beings as well as things. 24 See Mencius, 7A4. 25 Wing-tsit Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, 699. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 15 Don Sik Kim Humankind’s Nature in this sense is acquired by oneself and is, therefore, a part of oneself, although one’s originally good nature is inherited from the ‘Heavenly Nature.’ Chang Tsai made clear that “Heaven’s sequence” or “Heaven’s orderliness” identifies with li or ‘Principle’. What Chang Tsai seems to implying here is that there must be ch’i present and something which he calls li or ‘Principle’ in the universe.26 He writes further (chapter 5), “It is a Principle (li) that nothing can exist independently in itself.” Principle (li), according to him, is “definite, self-evident, and self-sufficient.” It is in each and every thing as well as ch’i. As new things appear, new principles are realized. But all principles are at bottom one, called the Great Ultimate. As such it is universal, unchanging, and transcendental. However, for him, “li is simply the concrete pattern in the activities of ch’i. Hence li is confined and contextualized in ch’i and particularities of things, which would make li more particularistic than universalistic.”27 The activity of change in ch’i or the transformation of ch’i is a process of creativity and self-transformation, for its gives rise to everything and all life. Therefore, it is a movement of generation and production. It is significant that Chang Tsai stressed the notion of creative production (sheng-sheng) and its products (sheng) in explaining the cosmological and ontological nature of ch’i. He considered sheng (life, production, generation) as the manifest function of transformation of ch’i. The creativity of ch’i is continuous as well as purposive. It is purported to preserve life and to continue life by making the creative activities of life the constant activity of reality. In summary, ch’i, for Chang Tsai, is the total reality. It is the reality of change between the yin and yang. Furthermore, it is a creative process of life, which is full of novelty. It is infinite and 26 27 Ibid., 482. Chung-ying Cheng, New Dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian Philosophy (SUNY Press: Albany, 1991), 16. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 16 Don Sik Kim indeterminate in its potentiality and yet contains all the possibilities of formation, transformation, and organization. The most important thing is that ch’i is both a creative agent and an agent for ordering and organization. The significance of Chang Tsai’s metaphysical position is that it provided a comprehensive explanation of change that could then be related to the dynamics of spiritual growth in human beings. Because change is affirmed as purposive process, and humans are called upon to identify with change and participate in the transformation of things. In this way, the Neo-Confucian way of thinking on ch’i and li is interwoven with the cosmology and ontology in the East Asian worldview. From this point, I want to illustrate the story of a woman’s healing in the Gospel in the light of the East Asian views on the body as a totality of body, mind and spirit, not only the body of the individual but also the body of whole cosmos in the interplay of yin and yang principle. Illness from the point of East Asian view is the unbalanced way of understanding to the relationships of the individual internally within the body and externally within the entire cosmos, society, nature, human relations, and so forth. For this reason, we will begin the story of the woman who had suffered the flow of bleeding for twelve years in the New Testament, Gospel of Mark Chapter 5:24-34. Perhaps more than any other, this healing story plunges us deeply into the dimensions of the body, and shows us the body as a field of energy. Now interestingly enough this touching experience does not come from any promises of salvation by Jesus. It is located solely in her body. It is purely bodily well-being. And it is something that she has got for herself. The one who also feels something is Jesus. He does not know where his energy has gone. Jesus experiences the truth about himself and his body, which is a human body, but full Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 17 Don Sik Kim of divine powers, of life-giving energies which he can communicate to others. God is there in bodies and their energies, alive and active. And the truth about this body is also that here it releases forces which make another body healthy. The interpretation which Jesus finally gives to the story goes beyond an individual framework. “Go in peace (shalom),” it is translated “Go in wholeness” in a deeper study the Greek term.28 What he literally says is ‘Go in wholeness — shalom.’ Shalom points to the time of salvation in which it is not just the individual who experiences peace and well-being but the whole creation, all society, all peoples. In this respect, this embodied experience, which proclaims the purely bodily healing, shows her complete liberation or salvation from the community, where she was regarded as a “sinner” or an “outcast.” For the Jewish social and religious view, the ‘flow of blood’, taken from the Old Testament laws in Lev. 15:25, posits a person unclean and therefore leads one to social and religious isolation from the community. Her illness thus was regarded as “dis-ease.” Through her healing, which took place in the body, we imagine that she has experienced the salvation with health, freedom, enjoyment and restoration of her boundary.29 The dualism, which divided body and Spirit, body and mind or soul, drew its spiritual capital from division, I have not seen the body in the holistic view of the East Asian understanding. It is a new continent to explore the body as a mysterious microcosm in liking to the macrocosm of cosmos from the cosmo-anthropological perspective. This See Harper’s Bible Commentary, James L. Mays, ed. (Harper & Row, Publishers: San Francisco, 1988), 991. “In the biblical sense of wholeness” is related to “peace.” And further note the relation of the Latin integer (unit, whole) to the Greek root so (unit, whole), as in sodzein (to save, ta make whole), soter (savior, the one who makes whole), and soteria (salvation, wholeness). 28 See also Moltmann, God in Creation, 274-275. Moltmann insists: “Illness, that is to say, is experienced as a malfunctioning of the organs of body, as a shaking of personal confidence, as loss of social contacts, as a crisis of life itself, and as loss of significance. This means that the healing of a sick person cannot be viewed in a single dimension” Ibid., 275. 29 Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 18 Don Sik Kim story makes clear how central the body of God (of Jesus) and the human body (the woman’s body) once were in Christianity and how they could motivate us, with our knowledge of the loss of our bodies as the loss of ourselves and of the interchange between body and energy or body and Spirit, to ask new questions about our bodies in the present. The body, for long a scientific object, matter to be treated and dominated, proves to be ‘terrible’ and ‘remarkable.’ It is a new continent to explore, a mysterious microcosm, like the nature (tzu-jan) which has just been rediscovered, something that human beings cannot approach as an object but of which we ourselves are always a part. Therefore, I believe that a new light is being shed on the body as the place in which many processes are articulated and as a primal experience of the way in which we are all interconnected from the East Asian arts of healing, which is known acupuncture. The continuity and unity between spiritual power and its material manifestation are clearly expressed in the light of ch’i. This organismic and dynamic worldview of East Asian cosmo-anthropological perspective is grounded on the conception of ch’i, which provides a basis for appreciating the profound interconnection of body and Spirit. Conclusion: A Global Conversation for Cosmic Pneumatology This task involves critically comparing the views of Barth, McFague and Moltmann with the East Asian cosmo-anthropological concept of ch’i and ferreting out the relative strengths and weaknesses of each perspective. To facilitate the endeavor I present these conclusions as a series of propositions or theses. In addition, this section is a continued defense of the overall thesis of this project, namely, that the fundamental concepts of human, world, and God must be reconceived in certain ways. This is, then, an attempt to argue for certain necessary changes in Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 19 Don Sik Kim anthropology, ontology, and theology. More exactly, a Christian ecological theology will be adequate to both to its own tradition and the current ecological crisis only if it moves beyond the dualistic dichotomy of nature and humanity, and Spirit and matter, accounts adequately for the spontaneity of nature, and takes seriously the “analogy of relation” in terms of the concept of ch’i from the East Asian cosmo-anthropological perspective. The first proposition is that an adequate ecological theology must develop and persuasively articulate an integral anthropology. This claim is supported by all three of the thinkers examined in this project. For example, Barth, McFague, and Moltmann all repudiate the typical dualism of body and soul (or spirit) and seek to construct a more holistic view of the human person. McFague rejects dualism because it legitimates both the subjugation of women and the exploitation of the nature. Moltmann rejects dualism, in addition to the above reasons, because seeing the world as home will occur only if we are at home in our bodies. In their rejections of typical dualisms, they rightly emphasize the interrelatedness between how we see ourselves and how we see the world of which we are a part. McFague is especially helpful in this regard for she presents a persuasive argument that links the dualism of body and soul with the domination of both women and nature. McFague argues that if the soul or spirit is viewed as not merely different than but of higher value than the body, and if the body represents matter, then that which is identified with the body--nature, women--will be devalued and dominated. Hence, looking from a feminist perspective, she argues that the dichotomy of spirit and matter, or soul and body, must be rejected if philosophy is to be liberated and spirituality properly conceived. McFague provides backing for the affirmation that a Christian ecological theology must incorporate a more holistic anthropology, that is, one which does not sanction the domination of women or the earth from the problem of the primary metaphors in the traditional idea of God. McFague contends: Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 20 Don Sik Kim This crucial characteristic of metaphorical language for God is lost, however, when only one important personal relationship, that of father and child, is allowed to serve as a grid for speaking of the God-human relaionship. In fact, by excluding other relationships as metaphors, the model of father becomes idolatrous, for it comes to be viewed as a description of God.30 McFague’s major contribution does not lie in systematic articulation; but if an ecological theology is to take seriously her perspective analyses and conclusions, then greater attention must be given to the development of a more sophisticated philosophical and theological anthropology that specifies in some detail just what a more integral or holistic view of the human being looks like. Likewise, Moltmann is instructive because of both the liabilities and the assets of his own view. For example, Moltmann retrieves the more holistic categories from the Bible in his attempt to fashion a theological anthropology. And his emphasis on humans as the ‘priests of creation’ is a helpful way of speaking of the human responsibility to represent God in creation. To be more specific, Moltmann points to the need for an expansive ethical orientation which includes justice for both non-humans and humans. For example, he argues that “we shall not be able to achieve social justice without justice for the natural environment, and we shall not be able to achieve justice for nature without social justice.”31 The concept of ecojustice is a necessary feature of any fully adequate ecological theology. With this insistence on viewing ecological wholeness and social justice as integrally related, for example, Ian Barbour claims: Poverty and pollution are linked as products of our economic institutions. Exploitation of man and of nature are two sides of the same coin; they reflect a common set of cultural values and a common set of social structures.32 30 31 32 McFague, Models of God, 97. Moltmann, The Future of Creation, 130. See also, Moltmann, God in Creation, 24, 320. Ian Barbour, Western Man and Environmental Ethics, 4. Or as David Tracy and Nicholas Lash simply state: “The struggle for justice must also include the struggle for ecology.” See David Tracy and Nicholas Lash, Cosmology and Theology, 90. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 21 Don Sik Kim McFague puts it as follows: “Christians, then, should be super, natural, for in our time, nature can be seen as the “new poor.”33 In order to resist the anthropocentrism and creatively present a vision and corresponding set of practices which emphasize the relational character of human existence in the world, McFague depicts many concrete, practical steps that enhance “community” between humans and nature as well as among people.34 This practice must include practices which initiate people into nature-friendly ways of living to establish and maintain ‘community’. McFague insists its point very clearly: We think in terms of major metaphors and models that implicitly structure our most basic understandings of self, world, and God. The basic model in the West for understanding self, world, and God has been “subject” versus “object.” Whatever we know, we know by means of this model: I am the subject knowing the world (nature), other people, and God as objects. It is such a deep structure in all our thinking and doing that we are not usually aware that it is a model.35 With this intrinsically relational concept of person, McFague also reminds us that humans are constituted not only by their relationships with other people but also by their relationships with the non-human world. Moltmann also emphasizes the inextricably communal character of human being and action when he argues that as imago mundi the human is “a being that can only exist in community with all other created beings and which can only understand itself in that community.”36 Moltmann asserts that the traditional modern paradigm must be replaced by a view in which human history is integrated into “the wider concept of nature.”37 McFague also proposes as one of her four criteria for a “theology of nature pertinent to the closing years of the twentieth century” that “it needs to see human life as profoundly 33 Mafague, Super, Natural Christans, 6. 34 Ibid., 115. Ibid., 7. 35 36 Moltmann, God in Creation, 186. 37 Moltmann, God in Creation, 125. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 22 Don Sik Kim interrelated with all other forms of life, refusing the traditional absolute separation of human beings from other creatures.”38 Ian Barbour concurs when he asserts that “the Christian tradition has too often set man apart from nature.”39 As David Tracy and Nicholas Lash succinctly state: “History cannot be understood without nature” and thus “contemporary Christian theology needs to recover a theology of nature, even to develop an adequate theology of history.”40 While the call to abandon the dichotomous dualism of nature and humanity is clear, the specific contours of an acceptable alternative paradigm of choosing a metaphor are as yet unclear, as evident by the various problems with the constructive proposals offered by McFague, Barth, and Moltmann. With Moltmann there is much clarity regarding what he proposes an alternative perspective. His suggestion that the creation might better be envisioned as the home of God eschatologically is helpful as far as it goes. In this regard, the concept of ch’i and te are closely related to a constructive alternative unity and interdependence of God and nature. For the idea of ch’i as a way of conceptualizing the basic structure and function of the cosmos signifies a symbolic metaphor to conceive the organismic harmony between nature and human worlds. And the idea of the transforming power of ch’i indicates that harmony will be attained through te, which is eschatologically achieved when one/it returns to one’s/its orginal nature (hsing) that is given by Heaven (or T’ien Ming) or Tao. This underlying message signifies that human life is a part of a continuous transformaion of ch’i that constitutes the cosmic process. As we have seen, the Mandate of Heaven is fully realized in one’s/its nature, that is, te which anticipates the eschatological fulfillment that all things are McFague, Imagining a Theology of Nature: The World as God’s Body,” in Liberating Life: Contemporary Approach to Ecological Theology, eds. Charles Birch, William Eakin, and Jay McDaniel (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1990), 203. 38 39 Barbour, “Attitudes Toward Nature and Technology,” 152. 40 Tracy and Lash, Cosmology and Theology, 87, 89. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 23 Don Sik Kim complete in us/it with letting things take their/its own nature. This ontological spontaneity of te is the conception of its immanent and transcendent potentiality of the Way (Tao) or Heaven in the East Asian cosmo-anthropological perspective. Regarding this, the ambiguity concerning the relationship between nature and humanity is that the concept of ‘nature’ (tzu-jan) itself is not clearly defined. The ambiguity to which I refer here is not that there are different views of nature, but that the idea itself is capable of being understood in more than one way. For example, R. G. Collingwood traces three different views of nature in the history of Western culture: nature as organism, as machine, and as evolving process.41 Claude Stewart explicitly focuses on this question about the nature of ‘nature’ and identifies at least three main usages of the term. According to Stewart nature can mean: 1) “that which stands over against ‘culture’ or human artifice”; 2) “the totality of structures, processes, and powers that constitute the universe,” not including God; and 3) the totality of reality including God.42 Stewart concludes that because of this ambiguity surrounding the concept of nature there is “considerable confusion concerning precisely what the theologian of nature is about.”43 Stewart asserts that “we conclude, therefore, that one of the immediate duties of the theologian of nature is to engage in a critical examination of the concept of nature.”44 In other words, the most common concepts of nature entail certain metaphysical assumptions which should not go unchallenged by Christians. In addition to these, Paul Santmire asserts that neither cosmocentrism with its “ethic of adoration” nor 41 R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of Nature (Oxford: Oxford University, 1960). But Collingwood himself often confuses two particular concepts of nature. Most often nature means the “totality” of reality; it is defined, as he himself says, in terms of cosmology. However, nature also means the non-human “part” of reality. And these are only two of several concepts of nature often not distinguished from one another. 42 Claude Stewart, Nature in Grace, 239; cf. 155. 43 Ibid., 237. 44 Ibid., 238. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 24 Don Sik Kim anthropocentrism with its “ethic of exploitation” is adequate since both tacitly assume a dualism between nature and humanity, differing only in which has priority.45 All of these above contentions may perhaps best be summarized by the claim that an adequate ecological theology must take more seriously the spontaneity of ‘nature’. That is to say, the common view of nature as ‘natural’ surroundings must be replaced by a perspective in which ‘nature’ (tzu-jan: being-so of-itself or spontaneity), as the interaction of yin and yang in Chang Tsai’s thought, is understood not only as the organic whole of what it exists, but also as the principle that everything must follow (te: innate power or virtue).46 From this perspective, the immanence of the Way is ontologically and eschatologically realized by the ‘not yet’ potentiality of its own te, that is, it can be characterized interchangeably in terms of nature (hsing) or nature (tzu-jan). Thus, as we have observed in Chang Tsai’s philosophy nature (tzu-jan) and te are identified with ch’i or tai-ch’i from the organic, dynamic and holistic view of the East Asian cosmoanthropological perspective. As mentioned previously one of the central issues with respect to theology proper is how best to conceive of the relations of God to the world and the world to God. Langdon Gilkey nicely summarizes a number of the important issues at stake in this discussion: The immanence of God in creation follows as a polar concept to the divine transcendence, as the symbol of providence is entailed in that of creation. God is both transcendent to creation and therefore absolute, and at the same time immanent and participating in or relative to creation.47 Paul Santmire, “The Future of the Cosmos and the Renewal of the Church’s Life with Nature,” in Cosmos as Creation, 270. 45 46 See Chang Chung-yun, Creativity and Taoism (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc, 1963), 125 Langdon Gilkey, “Creation, Being, and Non-Being,” in God and Creation, 229. Gilkey contends that this claim has a number of important implications for the “interrelations between God, the human, and nature.” for example, he argues that in such a view of God and creation “nature and humankind are implicitly and deeply related to one another; both have value as God’s creation; both reflect the divine life, order, and glory; and both participate in the divine purpose of redemption and reunion,” Ibid., 230-231. 47 Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 25 Don Sik Kim McFague, Barth, and Moltmann all support this claim. That is, they all attempt to articulate a model of God which rejects both monism and dualism and affirms both divine transcendence and immanence of God in nature. Moltmann affirms divine transcendence even though his emphasis on the nature and function of the Spirit is designed to reconceive God as profoundly present in the world. McFague also argues that viewing the world as God’s body more adequately captures the immanence of God vis-a-vis the world without necessarily reducing God to the world. Regardless of which specific model is employed, however, an adequate ecological theology must give serious attention to this issue of models for the God-world relation and, in particular, to the topic of divine agency. An ecological theology will be deficient if it fails to affirm and articulate the reality of the Spirit. In short, the typical view of the Spirit must be replaced by a vigorous acknowledgment that the Spirit is the authentic and pervasive presence of God in nature. The dualistic division between God and the world, or human beings and the world is closely related to the social structure which exalted the human over the world. Thus, we can conclude that dualism is intrinsically anthropocentric and hierarchical in the relationship of God-world and of human-world. For that reason, Barth uses the concept of analogia relationis to describe the correlation between God and human and between human and human to the relationship between the Father and the Son within the innertrinitarian life of God.48 For in his view all the works of God ad extra are integral parts of the one eternal will and plan of God which took shape in His eternal 48 Herbert Hartwell, The Theology of Karl Barth (Philadelphia: The Westerminster Press, 1964), 56. This analogy plays an important part in Barth’s doctrine of creation, in particular in his teaching on the image of God in human. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 26 Don Sik Kim decree in and through the person of Jesus Christ. Consequently, creation is rooted in that decree, which is its eternal basis and in which, so to speak, God’s future works of creation, reconciliation and redemption are anticipated.49 As Barth engages in reinterpretation of the imago Dei, he attempts to expound his theological anthropology by way of the analogia relationis and the imago Dei, as it is most simply, universally and concretely expressed in the marital covenant of man and woman.50 In the light of his doctrine of analogia relationis, Barth develops the doctrine of the Trinity under the rubric of revelation. In this respect, for Barth, the categories of “form” and “content” are used to delineate two interdependent aspects of human existence. The form refers to the structure and given context of human existence while the content refers to the appropriate and correlating action of human existing. For Barth the form of human existence is that of having being by virtue of being in relationship, to God and to other human creatures. This unity of being in form and action in is similar to his understanding of the being of God. For Barth this unity of the relational form of being and actional content of human existence constitutes humankind as a personal being in the image of God.51 Moreover, Barth holds that because of the character of the imago Dei “God’s grace takes place in the individual as such and in the I-Thou relationship as the form of life common both to God as the Triune God and to man as a being in relationship, related 49 Barth, CD, III, 1, 11, 42, 49, 94, 228. Barth claims that his doctrine of creation is intrisically trinitarian in its ontology, that is, creation is the external basis of God’s covenant of grace with human and that this covenant is the inernal basis of creation. 50 Moltmann, God in Creation, 241. 51 Barth, CD, I/1. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 27 Don Sik Kim to God and created male and female.”52 Hence, “with Barth the image of God in man is neither a quality in man nor something which man can seize upon and possess but a relationship which in its structure corresponds to a similar relationship within the inner Being of God and, whenever it reflects the latter qualitatively, has the character of an event of grace.”53 Moltmann also states that “likeness to God means God’s relationship to human beings first of all, and only then, as a consequence of that, the human being’s relationship to God.”54 Here the description of Barth’s anthropological imago Dei and the ‘analogy of relation’ show how my exegesis on the East Asian correlative ontological perspective is validate and helpful. That is, the imperative (Heaven’s mandate or Tao) is grounded on the reality that has been given (nature or hsing), appeals to it and is intended to bring it out to full actualization (te). More specifically, we can see this dynamic analogy of relation in the existence and interaction of ch’i in nature (tzu-jan) including human beings. To put it differently, for example as we will see later, according to Tung Chungshu in his description of the nature of people (min), actualities are the ‘basic stuff’ (chih) of a person’s natural tendencies (hsing), and by virtue of their nature people have the ‘not yet’ capacity (te) to awake from their state of ignorance and become good.55 Thus, the East Asian cosmo-anthropological ontology can be examined that a name as an example of hsing (given potential) ought to be appropriate to an actuality (nature natured) by virtue of the correlation that exists between them and this correlation is determined by the 52 Hebert Hartwell, Ibid, 180. 53 Ibid., 181. See also Barth, CD, III, 2, 325. 54 Moltmann, God in Creation, 220. 55 Wing-Tsit Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, 275. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 28 Don Sik Kim way things ‘naturally’ (Heaven or te) are.56 Implicit in Barth’s argument is that Godgiven potential (Mandate of Heaven or hsing from the above ontological view) ought not be unrealized. Barth’s analogia relationis implies an ontological givenness of an intrinsic potential for the God-world relation. In Barth’s view, as we have seen above, the analogy of relation is expressed by the ‘covenantal’ relationship between God and the world. Put differently, such a view can be understood as Moltmann’s use of the concept of zimzum (self-emptying, self-humiliation or self-limitation; in other words, kenosis).57 For Moltmann, the world is in God only because God has withdrawn himself and provided a space for the world to be.58 This creative thinking gives an important implication for the purpose of elucidating thinking on the correlation of nature and Spirit and on the correlation of a micorcosmic and macrosomic model of reality in the East Asian worldview. However, Moltmann points out, “only the human being is imago Dei. Neither animals nor angels, neither the forces of nature nor the powers of fate, may be either feared or worshipped as God’s image or his apperance or his revelation.”59 “Only human beings know God’s will, and only they consciously praise and magnify God.”60 Besides, In order to help better understanding for this, the writer wants to employ the term ‘nature natured’ (natura naturata) from Spinoza’s phrase: Natura est natura naturans. According to Moltmann, “consequently ‘the nature that is finally manifested’ is to be found in the context of the future -- the future of the alliances which mediate between human beings and nature.” Thus, Moltmann states, “according to Bloch, Spinoza’s idea of natura naturans presupposes the profounder idea (which probably derives from the Kabbala) of the natura abscondita, which thrusts towards its manifestation.” Moltmann, God in Creation, 43, 212. 56 57 See Moltmann, God in Creation, 86-87, 102. 58 Ibid. 59 Ibid., 221. 60 Ibid., 224. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 29 Don Sik Kim Moltmann argues that the Spirit is a subject. Moltmann criticizes Barth for precisely this reason, namely, that he fails to affirm that the Spirit is a person or subject. “For Barth, he [the Spirit] is then an energy but not a person. He is then a relationship but not a subject.”61 Moltmann states that “according to Barth the Spirit is nothing other than the subjective reality of God’s sovereignty. The Spirit is ‘the principle which makes the human being into a subject’.”62 In other words, for Barth, states Moltmann, “‘the human being is the ruling soul of his body, or he is not a human being’.”63 Moltmann clearly states that “Barth preserves the Platonic primacy of the soul to the body in a relationship of ownership.”64 Likewise, Moltmann points out that “the history of Western anthropology shows a tendency to make the soul paramount over the body which is thus something from which the person can detach himself, something to be disciplined, and made the instrument of the soul.”65 The relationship of heaven to earth in cosmology, the relationship of the soul to the body in psychology, the relationship of man and woman in anthropology, all correspond to the same order -- to mention only the correspondences in the doctrine of creation. In his account of these analogous structures of dominion, Barth is following the ancient metaphysicians, especially Aristotle, who even then treated heaven and earth, soul and body, man and woman, according to the same pattern.66 61 Moltmann, The Trinity and the Kingdom, 126. 62 Ibid., 253. Barth, CD, III/2, 364. 63 Ibid. Barth, CD, III/2, 495. 64 Ibid., 252. 65 Ibid., 244. 66 Ibid., 255. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 30 Don Sik Kim Yet, Moltmann asserts that the relationship between God and the world must be characterized in terms of “mutual need and mutual interpenetration.”67 Moltmann argues that “as a perichoretic relationship of mutual interpenetration and differenciated unity, we shall not introduce one-sided structures of dominion into it.”68 As stated previously, Moltmann puts it, “our starting point here is that all relationships which are analogous to God reflect the primal, reciprocal indwelling and mutual interpenertration of the trinitarian perichoresis: God in the world and the world in God.”69 Moltmann thus affirms that “through his Spirit God himself is present in his creation. The whole creation is a fabric woven and shot through by the efficacies of the Spirit. Through his Spirit God is also present in the very structures of matter.”70 “It is not merely the spirit of God that is present in the evolving world; it is rather God the Spirit, with his uncreated and creative energies.”71 Moltmann asserts that “we have to understand the Spirit as the creative energy of God and the vital energy of everything that lives.”72 Also Moltmann links the energies of the Spirit with the potentialities of the Spirit. As we have seen, McFague also suggests that “its panentheistic form of the world as God’s body and God as its spirit” radicalize “both divine immanence (God is the breath of each and every creature) and divine transcendence (God is the energy 67 Ibid., 259. 68 Ibid. 69 Ibid., 9; cf. 98. 70 Ibid., 212. 71 Ibid. Cf. Here also Peacocke, Creation and the World of Science, 203, who restores pan-entheism to favor, in order to link God’s transcendence with his immanence. 72 Moltmann, The Way of Jesus Christ, 91. Wesleyan Theological Society, 2008 31 Don Sik Kim empowering the entire universe).”73 Likewise, McFague states, “we joined the agential and organic models in order to express the asymmetrical and yet profoundly interrelational character of the panentheistic model of God and the world.”74 In this respect, these two modes of divine self-manifestation of the Spirit, creative energy of God and vital energy of all that exist, are obviously closely related to the cosmo-anthropological concept of ch’i. As Moltmann insists, we have to understand the Spirit as ch’i is the creative energy of God and the vital energy of everything that exists with the potentialities of the Spirit. As Moltmann frequently claims, the Spirit as ch’i is a way of more precisely explaining his version of panentheism that God is in the world and the world is in God. Thus, I propose a need to revision the traditional anthropocentric and dualistic metaphor of God for a more appropriate inclusive and relational metaphor of God as the Spirit, specifically ch’i as the creative energy of God and the vital Spirit of God. 73 McFague, The Body of God, 150. 74 Ibid., 149.