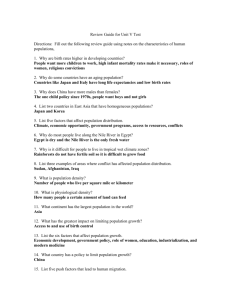

South-South migration, human development and MDGs

advertisement