Barrel One - Let them Eat Prozac

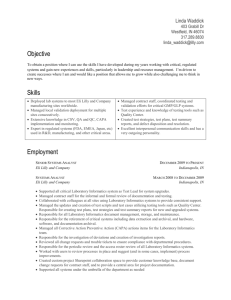

advertisement