poetry - Haiku Learning

advertisement

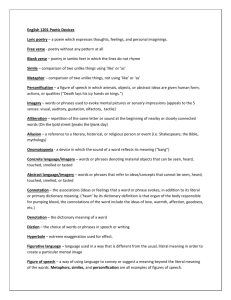

POETRY I. Some Types of Poetry A. Lyric a brief subjective poem marked by imagination, melody; it creates for the reader a single unified impression; usually abstract – based on revealing emotion. The name comes from the Greek lyre, a stringed instrument the ancients played to accompany the singing and chanting of verse. B. Narrative poetry that tells a story. i.e. ballads, epics C. Epic a long narrative poem constructed on a grand scale which celebrates the heroic deeds of men and gods. Examples are Beowulf, The Iliad, The Odyssey. D. Ballad a narrative poem originally meant for singing. Most ballads follow a standard four line stanza form which concludes with a refrain. Examples include The Cremation of Sam McGee and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. E. Dramatic Monologue F. Sonnet a narrative poem in which everything is presented from a single point of view, that of the speaker. The person to whom the speaker talks must be inferred as one reads the poem. Examples are Tennyson’s Ulysses and Browning’s My Last Duchess. a lyric poem of 14 lines, traditionally in iambic pentameter. There are two traditional kinds: Italian (Petrarchan): divided into an 8-line octave and a 6-line sestet with the rhyme scheme abba abba cde cde. Usually the octave states a problem or asks a question, and the sestet resolves the problem, or answers the question. English (Shakespearean): has 4 divisions: three 4-line quatrains, and a final 2-line couplet with the rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg. The couplet usually serves to thematically summarize or unify the ideas stated in the three quatrains. G. Ode a thoughtful, usually formal lyric poem of exalted tone. The ode was originally a choral interlude in Greek drama and later developed as an independent composition. The most famous might be Keats’ Ode to a Grecian Urn. H. Elegy a lyrical poem on death. When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed is Walt Whitman’s elegiac lament for the death of Abraham Lincoln. II. Some Verse Forms and Stanza Patterns A. Blank Verse unrhymed iambic pentameter. Shakespeare wrote his plays in Blank Verse. B. Structured Poetry poetry in which there exists a fixed pattern of rhyme scheme and meter. Sonnets, limericks and villanelles are examples of structured poetry. C. Free Verse unstructured poetry (i.e. no fixed rhyme scheme or meter). D. Stanza a repeated unit having a similar number of lines which follow a similar rhythmical and rhyming pattern. A ‘paragraph’ of poetry. E. Refrain a repetition of a fixed pattern of words; the chorus. F. Quatrain a poetic stanza of four lines G. Couplet two line linked by rhyme H. Heroic Couplet a series of iambic pentameter couplets as in Pope’s The Rape of the Lock or Chaucer’s Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. I. Caesura a pause or break in the metrical or rhythmical progress of a line of verse. J. Enjambment when one line in a poem is “run on” to the next by an absence of any punctuation at then end of the first line III. Sound Devices A. Onomatopoeia words whose sounds imitate their meanings: buzz, hiss, boom, crack… B. Alliteration repetition of initial consonant sounds: A slithering snakes slides to swampy solace. C. Consonance the repetition of the same consonant sounds with different vowel sounds: pitter, patter; slimmer for summer. D. Assonance the repetition of vowel sounds either initially or internally: While in the wild wood I did lie – a child with a most knowing eye… Poe’s Romance. E. Meter and Scansion Meter is the name given to the pattern of accents and stresses used by the poet to establish a rhythm. To scan a poem, you must determine where the stress falls and then count the number of accent or beats per line. In doing so, you must decide what the poet wishes to emphasize, thus, scanning can lead to a better understanding of the meaning of a poem. A X.J. Kennedy once wrote: It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing! 1. Principal Meters of English poetry: (~ = unaccented syllable; / = accented syllable) Iamb (~ /) re-port, in-tense Trochee (/ ~) ta-ble, fa-ther, cry-ing Anapest (~~ /) in-ter-rupt, un-der-stand Spondee (/ /) Go Now! Dactyl(/ ~~) beau-ti-ful, com-pa-ny The following poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge may help you remember your metrical feet: Trochee trips from long to shorter. From long to long in solemn short Slow Spondee stalks; strong foot; yet ill able Ever to come up with Dactyl trisyllable. Iambics march from short to long. With a leap and a bound the swift Anapests throng! 2. Metrical Patterns classified by length: Mono+meter = monometer, or a meter using one foot per line. Dimeter two feet Trimeter three feet Tetrameter four feet Pentameter five feet Hexameter six feet Octameter eight feet 3. Scanning a line: ~ / ~ / ~ / ~ / ~ / But soft! What light through yon-der win-dow breaks? The repeated metrical foot here is the iamb and there are 5 of them, hence this is a line of: iambic pentameter. Adjective forms of metrical feet: Iambic Trochaic Anapestic Dactylic Spondaic Thus the following comment on microbes is written in trochaic monometer: “Adam had ‘em.” The key to understanding meter and scansion is to recognize that absolute regularity of rhythmical pattern would be deadly dull. Consequently, you must train yourself to scan quite a few lines to try and determine which metrical pattern is predominant in the poem. F. Cacophony a combination of harsh, unpleasant sounds or tones G. Euphony a combination of pleasant, soft sounds or tones H. Rhyme the repetition of vowel and consonant sounds 1. Masculine Rhyme: the rhyme falls on a single stressed syllable: old/bold, sad/bad 2. Feminine Rhyme: the rhyme falls on a stressed syllable followed by one or more unstressed syllables: older/bolder, withering/slithering 3. Internal Rhyme: the rhyme comes within a line of poetry: “While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.” - from The Raven (Edgar Allan Poe) 4. Slant Rhyme: the poet deliberately uses similar but not identical sounds. Slant rhyme usually has a disturbing effect and a poet my use it to emphasize a lack of harmony in some subject: love/move, lost/most, sharp/shape, shine/shame, tail/tall etc. 5. Half-rhyme: rhyming of the fist and last consonants, with a different vowel sound in the middle: flip / flop seen/ sign I. Anaphora a rhetorical figure of repetition in which the same word or phrase is repeated in (and usually at the beginning of) successive lines, clauses or sentences. (adjective: anaphoral or anaphoric) J. Syncope a kind of verbal contraction by which a letter or syllable is omitted from within a word (heav’n for heaven and o’er for over) (adjective sycopal or syncopic) IV. Figurative Language A. Metaphor The usual strict term describes comparisons between two unlike things (not using the word like or as). Such comparisons may be established in a single word, or they may be developed throughout an entire poem (in which case it is called an extended metaphor). Try to avoid mixing metaphors as the effect is often confusing for the reader. For example, the following is silly: “In order to keep ahead, we must keep our ears to the ground and our eyes on the ball.” There are different types of metaphors: 1. Simile: comparison between two unlike things using the word like or as: “She is lovely as a rose.” “He works like an ox.” 2. Metaphor in a noun: “Mom looked at me with daggers in her eyes.” 3. Metaphor in a verb: “The branches scratched at the window pane.” 4. Metaphor in an adjective: “My bloody thoughts were obvious to all but him.” 5. Metaphor in an adverb: “The wind moved nervously across the plain” 6. Personification: Giving animate (human) qualities to an inanimate object: “The blaring car horns argued on the busy street.” 7. Conceit: A far-fetched simile or metaphor, a literary conceit occurs when the speaker compares two highly dissimilar things. “I have been studying how I may compare / this prison where I live unto the world” B. Metonymy: a figure of speech in which something very closely associated with a thing is used to stand for or suggest the thing itself: “Three sails floated into the harbour.” The sails stand for the ships themselves. Note: Metonymy and Synecdoche (below) are so similar, they are often used interchangeably C. Synecdoche: a form of metaphor where in mentioning a part you signify the whole. Slightly different than metonomy in that the part selected to stand for the whole must be the part most directly associated with the subject under discussion. “All hands on deck,” refers to the workers, not simply their hands. Note: Synecdoche and Metonymy (above) are so similar, they are often used interchangeably. D. Apostrophe: addressing a dead or absent person (or quality) as if he/she were present. “Shakespeare, tell me a pun, and make my passage jocund and fun.” E. Pun: a play on words based on the similarity of sounds between two words with different meanings. “You have dancing shoes with nimble soles, I have a soul of lead” - Romeo and Juliet (Shakespeare) “Pork stew is much ado about mutton” F. Denotation: the dictionary meaning of a word or phrase (it is non-emotional) G. Connotation: the additional meaning a word acquires through traditional usage or because of its context. Not all words are connotative, but they are all denotative. Note the difference between horse/steed, house/home, skinny/thin, dog/mutt, fat/plump. H. Imagery those things which we know through one or more of our five senses (sight, sound, touch, scent and taste). Often authors create “pictures” in our mind but they may also jar our senses of touch, sound, scent and taste through inventive word choice and phrasing. They will also use imagery to try to explain abstracts such as love, jealousy and grief because we always respond more strongly to images than to abstractions, which are hard to imagine or “feel”. Imagery is a major building block in both poetry and prose. 1. Visual imagery: My love is like a red, red rose 2. Aural imagery: And fired a shot heard around the world 3. Olfactory imagery: The winter evening settles down smell of steaks in passageways 4. Gustatory imagery: I always like summer best / you can eat fresh corn from daddy’s garden 5. Tactile imagery: Life is a barren field, frozen with snow I. Symbol: an image which is what it is, but also stands for something more than what it is. Traditional symbols like a red rose (love), a black cat (evil) or a dove (peace) abound in literature, but skilled authors will also create symbols in their works by repeatedly using them in a number of similar situations (ie. The conch in The Lord of the Flies (Golding) or the cliff in Catcher In The Rye (Salinger))In the phrase,“You can’t teach an old dog new tricks”, the dog is a symbol as it can stand for other living creatures besides dogs. J. Allegory: a narrative or description which has a second meaning beneath the surface one. In an allegory, what is really important is the implied meaning. Allegories can also be written in the form of parables or fables. i.e Lord of the Flies is an allegorical story which reveals a underlying truth about the inherent savagery of human nature. K. Allusion: a reference to something in history or previous literature which reinforces the ideas or emotions of the piece of literature you are reading. Authors often allude to Greek or Roman Gods, Biblical Characters or Historical People to enhance or develop the character or situation they are writing about. L. Oxymoron: a terse combination of contradictory on incongruous terms: “living death” “mute cry”, loving hate”, “painful laughter” M. Paradox: an apparent contradiction which, upon further analysis, holds a profound and insightful truth. Poets use paradoxes because they have shock value, and are a complex, intelligent manner in which to make a point. Phrases like “Back to the Future”, or “The Sound of Silence” don’t seem to make much sense until they are studied. Paradoxes can be thought of as “graduated oxymorons”. Other examples: “He is filled with emptiness”; “Loneliness is a great thing to share.” N. Hyperbole: over exaggeration for effect (usually comical). “It rained buckets last night and my yard is a lake!” O. Understatement: saying less than one means; deliberately under-emphasizing for effect. “A man who holds his hand in the fireplace for half an hour is liable to experience a sensation of excessive and disagreeable warmth.” P. Irony: a discrepancy/contradiction between appearance and reality a) Verbal Irony - saying the opposite of what you mean. Very much like sarcasm though not implicitly scathing. “Take your time. We’re in no rush…” “Gee, I really like your new haircut!” (snicker, snicker…) b) Irony of Situation - when the opposite of what you expect to happen occurs. The Gift of the Magi (O’Henry) is a famous example of and ending with Irony of Situation. c) Dramatic Irony - when a character in a piece of literature does not fully understand the implications of an event, an action or a spoken word, but we, the reader do.. Very common in horror movies where the heroine goes into the basement while we know the bad guy is already down there! V. Tonal Devices A. Tonal Devices are the ways in which an author conveys his feelings or attitudes about The subject he/she is describing to the audience. No author would go to the trouble of writing a detailed poem unless he/she felt strongly about the subject. That defines the tone they take with the work. Good readers must take the time to look for tonal words (any words which seem to be specifically because they convey the poet’s emotional attitude. Some words that describe tone: ironic, playful, dictatorial, sarcastic, doubtful, curious, formal, solemn, serious, hateful, intimate, informal, adoring, disgusted, accusatory, empathetic, indifferent, optimistic, hopeful, condescending, flattering, conniving etc… VI. Other Literary Terms: A. Allusion reference to a person, place, or event which the reader already knows B. Ambiguity a situation in which more than one meaning or interpretation is possible or expected C. Colloquial ordinary everyday language and speech D. Mood the atmosphere or feeling created by a literary work, partly by a description of the objects or by the style of the descriptions. A work may contain a mood of horror, mystery, holiness, or childlike simplicity, to name a few, depending on the author’s treatment of the work E. Diction An author’s choice of words. Since word have specific meanings, and since one’s choice of words can effect feelings, a writer’s choice of words can have great impact of a literary work. The writer, therefore, must chose his words carefully F. Syntax The manner in which an author uses sentence style in a poem. Sentences may be complex, laborious excursions which imply a reflective, introspective tone; or they can be choppy, staccato phrases which convey hesitance, confusion, shock or, possibly even build suspense. Keep an eye on how syntax (both sentence length and sentence style) is used by an author to elicit a response from the reader