The Annotated Bibliography of Settlement and Neighbourhood

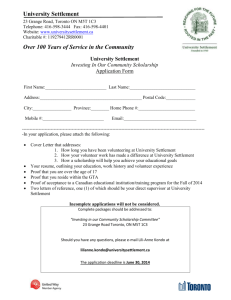

advertisement