A birds eye view of the tiny Ugandan nation would reveal a social

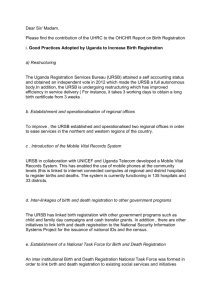

advertisement