Prohibition and Crime - AP-United-States

advertisement

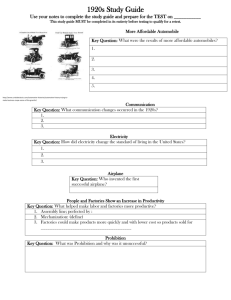

Prohibition and Crime 1. According to those who supported prohibition, what was prohibition supposed to accomplish? 2. What problems did prohibition create for the United States? QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. 3. In the last paragraph of this article, we read that “wets held prohibition responsible for organized crime and pledged that with repeal, the immorality of the country . . . will be a thing of the past.” How was this idea just as naive as the expectations of the “drys”? 4. Why did prohibition fail? Many Americans greeted the advent of prohibition in January 1920 with unwarranted optimism. Prohibitionists had long promised that, given a chance, they would eradicate pauperism and improve the condition of the working class. They had also predicted a sudden reduction in crime since “90 percent of the adult criminals are whiskey-made.” Closing the saloons, many believed, would improve the nation’s physical health and strengthen its moral fiber as well, for drys were always saying that liquor “influences the passions” and “decreases the power of control, thus making the resisting of temptation especially difficult.” On the day the Eighteenth Amendment took effect, the evangelist Billy Sunday conducted a mock funeral service for John Barleycorn in Norfolk, Virginia. He prophesied: “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons in to factories and our jails into storehouses. . . . Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.” Prohibition, however, proved more attractive to some that to others, and the distinction often followed religious, ethnic, and geographic lines. Typically, prohibitionists were likely to be Baptists or Methodists rather that Catholics, Jews, Lutherans, or Episcopalians; old-stock Americans rather that first- or second-generation immigrants. They were more likely to live in small towns, and in the South or Midwest, than New York, Boston, or Chicago. Undaunted by accusation that they were narrow-minded fanatics striving to enforce conformity to their moral code, prohibitionists saw themselves as allowing a “pure stream of country sentiment and township morals to flush out the cesspools of cities and so save civilization from pollution.” At the heart of the struggle between wets and drys were contrasting cultural styles. The Eighteenth Amendment, ratified in January 1919 and ultimately approved by every state except Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey, contained several glaring loopholes. It did not forbid the consumption of intoxicating beverages but only their sale, manufacture, and distribution. As a result, those who could afford to store up an adequate supply were not terribly inconvenienced. Out of deference to property rights, liquor dealers were permitted a full year’s grace in which to wind up their business affairs. The amendment also failed to define the world “intoxicating” or to provide any means of enforcement. The Volstead Act (1920) attempted to remedy these deficiencies: it arbitrarily defined “intoxicating” any beverage with one half of 1 percent alcohol content, and it provided rudimentary enforcement machinery. Yet the task of enforcement proved truly Herculean, particularly in those communities where a majority saw no moral virtue in temperance. There seemed an endless number of ways to evade the law. People smuggled whiskey across the Canadian and Mexican borders, made denatured industrial alcohol palatable by adding chemical ingredients, prepared their own “moonshine” at home in onegallon stills, falsified druggists’ prescriptions, stole liquor reserved for legitimate medicinal and religious purposes in government warehouses, and pumped alcohol back into “near-beer” to give it more of a kick. Those administering the law encountered many difficulties. The Prohibition Bureau, understaffed and underpaid, was the target of a series of attempted briberies. Some evidently succeeded, for one of every twelve agents was dismissed for corrupt behavior, and presumably others were never caught. For all its inadequacies, the law almost certainly cut down on alcoholic consumption. But people who wanted to continue drinking, and those for whom liquor filled an important psychological need, managed to get around the law. Moreover, the attempt to enforce a moral code to which many did not adhere led to widespread hypocrisy and disrespect for the law. This received formal recognition when the Supreme Court ruled the government could request income-tax returns from bootleggers. The Court found no reason “why the fact that a business is unlawful should exempt it from paying the tax that if lawful it would have to pay.” The memoirs of a leading prohibition agent also testified to the laxity of enforcement. She related how long it took to buy a drink on arriving in different cities: Chicago-21 minutes; Atlanta-17 minutes; Pittsburgh-11 minutes. In New Orleans it took but 35 seconds. The agent asked a cab driver where he could find a drink; the driver, offering him a bottle, replied, “Right here.” Prohibition was associated not only with a cavalier attitude toward the law but also with a more sinister phenomenon: the rise of organized crime. Criminal gangs had existed in the past, but in the 1920s they evidently became larger, wealthier, and more ostentatious. Gangland weddings--and funerals--became occasions for lavish displays of wealth and influence. The 1924 funeral of Chicago gunman Dion O’Banion included twenty-six truckloads of flowers, an eight-foot heart of American beauty roses, and ten thousand mourners among whom were several prominent politicians. Gangs also became increasingly efficient and mobile as a result of the availability of submachine guns and automobiles. And they grew somewhat more highly centralized, dividing territory in an effort to reduce internecine warfare. Although criminals made money through control of prostitution, gambling, and racketeering, bootleg liquor provided a chief source of revenue. As organized crime blossomed, new theories arose to account for it. Sociologists at the University of Chicago, for example, argued that criminal behavior did not result form mental or biological inferiority, but represented a logical response to the environment. The gangster, growing up in a climate of lawlessness and graft, was simply a product of his surroundings. In his study of crime in Chicago, John Landesco noted that the gangster developed a self-image that legitimized his behavior. He viewed himself as doing what everyone else in America was doing--seeking wealth and power--but being more open about it. He thought of himself as satisfying a public demand for liquor and other illicit, but essentially harmless, pleasures. He perceived himself as a community benefactor who lent a helping hand to the poor. Indeed, Frank Uale was known as “the Robin Hood of Brooklyn,” and the “godfather of 1000 children.” A remark attributed to Al Capone summed up much of this rationale: “They call Capone a bootlegger. Yes. It’s bootleg while it’s on the trucks, but when your host at the club, in the locker room, or on the Gold Coast hands it to you on a silver platter, it’s hospitality.” By the end of the decade, opponents of prohibition had successfully turned the tables on its advocates. Once the drys had promised that prohibition would reduce crime; now the wets held prohibition responsible for organized crime and pledged that with repeal, “the immorality of the country, racketeering and bootlegging, will be a thing of the past.” Formerly the drys had claimed that prohibition would eliminate poverty; now the wets asserted that the liquor industry could provide needed jobs and revenue to a nation beginning to experience mass poverty in the Great Depression. Prohibition was repealed in 1933. Yet it failed less because it triggered a crime wave or weakened the economy than because it attempted the impossible: to regulate moral behavior in the absence of a genuine consensus that the proscribed behavior was, in any real sense, immoral.