View/Open

The American University in Cairo

A Thesis Submitted

To

The Department of English and Comparative Literature

May 2003

The Castaway:

A Comparative Study of Alienation in Franz Kafka’s The Trial and J.M. Coetzee’s Foe.

By

Alia Mohamed Taher Ahmed Tawfik Abou Zeid

For My Dear Parents:

My thesis is the most precious thing I can offer and dedicate to you.

I am grateful for everything you gave and taught me. If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have managed to get the Master’s degree and make a dream come true. Thank you for always being loving, kind, generous and supportive and may God bless you.

Your Daughter,

Alia Mohamed Taher

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my thanks to Dr. William Melaney, my thesis advisor for being very helpful and supportive. I would also like to express my gratitude for his assistance in enabling me to submit a strong thesis by providing useful and illuminating comments. I would also like to thank Dr. James Stone, my reader, who has also been supportive and with whom I took several courses that have added to my knowledge of literature and from which I greatly benefitted.

Abstract

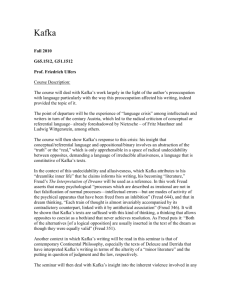

This thesis is a comparative study of alienation. It provides an analysis of the different ways in which the Czech writer, Franz Kafka, and the South African writer, J.M.

Coetzee delineate alienation in their works, The Trial and Foe . Three aspects of alienation are discussed: alienation from self, world and language. Hence, the thesis emphasizes that man’s predicament of alienation, homelessness and exile stems from a failure to recognize a self to which he can relate, an inability to find a home in an alien universe and an incapacity to develop a constructive relationship with words and language. This study not only focuses on man’s existential predicament of alienation, but it also reveals that alienation is an experience that writer and reader go through in their encounter with a work of art. Thus, this study also explores the nature of a work of art and is concerned with the effects of literature on the reader.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter One: The Self as a Stranger

Chapter Two: The World as a Strange Place

Chapter Three: The Nut without a Kernel

Conclusion

Bibliography

26

55

85

89

1

5

Sometimes I wake up not knowing where I am. The world is full of islands, said Cruso once. His words ring truer every day.

J.M. Coetzee,

Foe

, 71

Introduction

“I feel that I exist only outside of any belonging. That non-belonging is my very substance. Maybe I have nothing else to say but that painful contradiction: like everyone else, I aspire to a place, a dwelling-place, while being at the same time unable to accept what offers itself” (Patterson, x). With these words, Edmond Jabès sums up in From the Desert to the Book the predicament of “the twentieth-century figure of the alienated individual” (Seigneuret, 39) and “the homelessness of the modern human condition” (Patterson, ix).

Jabès’ words highlight the centrality of the theme of alienation in modern literature since it presents man’s situation and plight in the world. Alienation takes different forms in literature and several writers have attempted to delineate and express the different forms it takes and the causes that produce this terrible and dreary state which is at the core of man’s existence and being.

The experience and state of alienation is a dilemma that man encounters as he enters the world and struggles to deal with and overcome it throughout his life. Man’s experience of alienation starts from his first day on earth as he is born and this is evident in the fact that his first introduction to life and earth is met with a cry. As the infant leaves its mother’s womb, it feels as if it has been deserted and expelled from its home, just as Adam and Eve were expelled from heaven and were doomed to a life of endless wandering and loss in the wide and difficult world.

Man’s life on earth is, therefore, a form of expulsion and an attempt to retrieve the lost paradise and home in which he would find his belonging and place in the world. In his attempt to find his dwelling-place, man attempts to arrive at an understanding of the self, the world he is living in and the language he speaks.

However, as he seeks to achieve and develop a harmonious relationship with self, world and language, he is overwhelmed by their complexity and indecipherable nature. He realizes that these three categories that form the basis of one’s existence are doors he cannot enter or penetrate. As a result, he feels alienated from self, world, language and meaning.

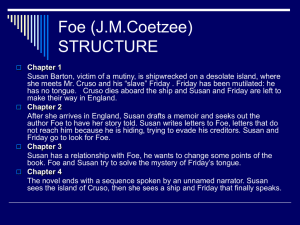

The Czech writer Franz Kafka and the South African writer J.M. Coetzee express in their literature man’s state of alienation from self, world and language. In

Kafka’s novel

The Trial and Coetzee’s Foe , the self emerges as a riddle that one cannot solve, the world is seen as a strange, unfamiliar and uncanny place into which

one cannot fit or belong and language emerges as extremely complex and labyrinthine. Meaning and interpretation are always either absent or ambiguous and, instead, emptiness and hollowness are prevalent.

In The Trial and Foe , one encounters characters and situations that highlight man’s estrangement and isolation from self and world. Joseph K. (the central character of Kafka’s The Trial ) and Susan Barton (the female narrator and central character of Coetzee’s Foe ) are infinitely embroiled in a battle against the silence and ambiguity of the self and the world. Their inability to decipher the self / world hieroglyphics is the major dilemma which results in their acute sense of alienation, aloneness and desolation in the world. Through these two characters’ endless attempts to comprehend and unravel the self / world mystery, Kafka and Coetzee reveal that man’s problem of assimilation or belonging stems from his inability to penetrate the dark alleys of the divided and dichotomized self and the meaningless, quizzical and unfathomable universe which he inhabits.

This study attempts to explore the different ways in which Kafka and Coetzee present and portray the experience of man’s alienation and utter isolation through a comparative study of their works. In addition, in the analysis of Kafka’s presentation of this theme, allusions are made to other major works (selected short-stories) by

Kafka in which this theme is clearly evident.

Through the study of The Trial and Foe , an attempt is made at showing that both Kafka and Coetzee reveal that alienation is not merely man’s plight in the world, but also that it is the reader’s plight before a work of art. This shows how their works are a commentary on the reader’s response to a work of art since they reflect the effect of literature and the literary experience on the reader. Like Joseph K. and Susan

Barton, who are forever lost in the labyrinth of an incomprehensible and puzzling universe, the reader finds himself trapped and entangled in complex and labyrinthine texts that resist interpretation.

Like Joseph K. and Susan Barton, the reader struggles to unravel the mysteries and enigmas of the text in an attempt to find meaning in this inscrutable world. The reader’s inability to find a trace of meaning through which he could be reconciled with the work of art makes him emerge from his experience with this literature of alienation as an embodiment of alienation himself. For like Kafka’s and Coetzee’s marginalized protagonists, the reader feels cast out by the text. He ends his journey with Kafka and Coetzee with no certainty or answers. Instead, like Joseph K. and

Susan Barton, he finds himself constantly asking never-ending and unanswerable questions, the most important of which is: “where do I belong?” or “where does man belong?”

An individual chapter is devoted to each aspect of alienation. The first chapter, entitled, “The Self as a Stranger,” presents an analysis of Kafka’s and

Coetzee’s depiction of man’s alienation from the self. The major issues discussed in this chapter are: the self as a riddle and an enigma, the self and its existence as being questionable, the problem of “precarious and threatened individual identity”

(Seigneuret, 14). The role of external forces in instilling the feeling of alienation and estrangement from the self will also be discussed, since an establishment and a definition of identity is dependent on these factors, rather than, simply on the individual’s perception of the self.

The second chapter, entitled, “The World as a Strange Place,” presents

Kafka’s and Coetzee’s depiction of man’s alienation, isolation and homelessness in a world that has become totally unfamiliar and uncanny. The following major points will be taken up: the causes behind man’s estrangement from the world, the problem of an incomprehensible world, the notion of difference and otherness that heightens the sense of alienation and desolation, the continual search for a destination and a place in which at-homeness is felt, the problem of the world’s silence which creates the feeling of being an outsider, the continual search for an oracle that would answer one’s questions and explain the puzzle of life, and the position of the writer as an outsider. With respect to the final points, the fact that Kafka is a Czech writing in

German and Coetzee is a South African writing in English is considered.

The third and final chapter, entitled, “The Nut without a Kernel,” examines the problem of the hollowness of words and language, the “sense of the betrayal of language” (Seigneuret, 41) and the palimpsestic text presented by Kafka and Coetzee as an attempt to reveal the reader’s experience of alienation before a work of art.

Within this context, the problem of the absence of a source or foundation on which one could depend for interpretation, “the absolute absence of coherence and meaning at the root of existence” (Seigneuret, 41), the problem of understanding the message and meaning conveyed by the text, and the problem of the literal-minded reader who fails to grasp the message of a work of art are discussed. These concerns are related to the web-like and labyrinthine quality of text and language, the text as an investigation that raises questions but offers no answers, the protean text which contains multiple

layers of meaning and the impossibility of clinging to a single interpretation. Finally, the elliptic text which conceals rather than reveals, the text and its double and the text in conflict with the world are critically examined.

Thus, the purpose of my study, “The Castaway: A Comparative Study of

Alienation in Franz Kafka’s The Trial and J.M. Coetzee’s Foe ,” is to explore and examine man’s existential predicament of alienation, homelessness and exile which stems from a failure to conceptualize or recognize a self to which one could relate.

The thesis centers around the plight of “the wanderer who can find neither peace nor a place to which he feels an attachment” (Seigneuret,38), his inability to find a home in a universe which is void of meaning and inability to establish relationship with words and language. The hollowness at the core of the self, world and language is what makes man’s life a difficult task in which he becomes doomed to a terrible existence based on perpetual and endless wandering. No Ithaka is ever arrived at and homelessness and alienation become man’s fate and share in life. This is the experience that Kafka and Coetzee express in their fiction.

Chapter One

The Self as a Stranger

All my life grows to be story and there is nothing of my own left to me. Nothing is left to me but doubt. I am doubt itself. Who is speaking me? Am I a phantom too? And you: who are you?

J.M. Coetzee,

Foe

, 133

The Sphinx’s riddle in Sophocles’

Oedipus Rex is what inspired me to explore the idea of man’s estrangement from self. The Sphinx’s famous riddle asked what being goes on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening. The answer to the riddle is ‘man.’ The fact that many people were doomed to death because of their failure to solve the riddle reveals the fatal effect of man’s ignorance of self, and the large number of people who fail to solve the riddle reveals the immensity of man’s self-estrangement since man fails to realize that the Sphinx is addressing the matter of human existence.

The Sphinx’s riddle is a kind of mirror in which man should see and recognize himself but, instead of revealing himself to him, it makes him see an unrecognizable stranger. He contemplates the riddle as if it were asking about the strangest and most alien existent creature, not knowing that he is simply its subject. The Sphinx’s riddle serves not only as a revelation of man’s smallness before the universe, suggesting that he is the most helpless being in it, forever groping in darkness and blindness, but it also conveys a very significant message, which is that man is himself a puzzle.

Oedipus’ ability to solve the Sphinx’s riddle comes as a sign of hope and a manifestation of the triumph of human intelligence. However, as the play develops, all hopes are shattered as Oedipus fails to identify himself and realize throughout the long investigation he carries out that he is his own enemy and the subject of his search and inquiry. Oedipus Rex reveals that Sophocles was prophetic since he foresaw the rise of psychology, which not only came as a promise to calm and soothe man’s

ailments, but also came as a thunderbolt that shattered the solid ground of man’s belief that he understands and knows himself. Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, had a very important message to pass on to humanity, which concerns the complex and quizzical nature of the human self.

Franz Kafka is a writer who manages to depict man’s plight of self-alienation through his presentation of the self as a riddle. In The Trial , Kafka presents a protagonist who wakes up one morning to find his room invaded by two strange men informing him that he is under arrest. However, nothing is told about the nature of his offense. Joseph K. ventures from this point onwards on an endless journey to discover why he is accused. His attempt to investigate into the nature of his offense is symbolic of his self-investigation. Thus, as in Oedipus Rex , the self becomes the object of a quest and a riddle that the individual strives to solve.

Joseph K. spends his entire life asking and waiting for the court and its officials to reveal to him the nature of his crime. This reveals the extent to which he is an alien to himself, since he needs to be told what his offense is by others, but he himself knows nothing about himself. This need to solve one’s own mystery by seeking external aid parallels a patient’s need to depend on a psychiatrist to help him unravel the complexity of his psychic ailment. Thus, Kafka reveals that man’s own self is the most bewildering puzzle he could ever encounter, and through Joseph K’s dependence on the court and its officials to explain the puzzle of his offense, he confirms Freud’s conclusion of the labyrinthine nature of the self and of “man’s own mystery unto himself” (Draper, 1944).

In his attempt to emphasize the enigmatic quality of the self, Kafka presents a kind of tabula rasa character. For nothing is known about Joseph K., his background, personality and thoughts. The only information given about him is that he is a bank clerk. The absence of information through which Joseph K. could be individualized gives the character an anonymous aspect. K., therefore, emerges as a “nondescript man, devoid of spectacular deficiencies and virtues” (Politzer,166) like Robert

Musil’s character in

The Man Without Qualities . This could make the existence of a self questionable and doubtful. It is as if Kafka is trying to say through the blank nature of Joseph K. that individual identity is merely a myth.

In addition, the fact that Kafka mentions Joseph K’s job as a bank clerk and makes this the only piece of information available on him reveals that the self vanishes but the function remains. The enigmatic and anonymous nature of the self is

further emphasized by the protagonist’s name. For one never knows what the initial

K. stands for. It stands as a puzzle and a reminder of the puzzle of the self, the absence of man’s identity and his existence as an unknown entity.

The absence of identity and its questionable existence is also evident in the fact that when the warders Franz and Willem invade K’s room, he searches for his identity papers but does not find them. The loss of K’s identity papers symbolizes the eradication of the self. Joseph K’s attempt to discover his crime is, therefore, an attempt to create an identity. Kafka reveals that the presence of a self and an identity is extremely doubtful in this world. He also reveals that identity has to be created and constructed, but that man is born with no identity and even if he has one, it can be either obliterated or forgotten. His work is, therefore, an “investigation of this forgotten being” (Kundera, 5).

The element of oblivion and blindness are also factors that bring about man’s loss of identity and his self-alienation. This is clear in the fact that when K. tries to reconstruct the event of the announcement of his accusation by the warders to his neighbor Fräulein Bürstner, he tells her who was present in her room and what took place, but then he tells her: “Oh, I’ve forgotten myself, the most important character”

(Kafka, 21). Here K. represents the state of “looking on oneself as something alien”

(Thorlby, 15) as Kafka describes it in his notes.

However, K. is not only alienated from self but also from the very fact of his existence, since his presence is the last thing that he remembers, and the focus of his attention is merely on the events that took place in his midst. His detachment and relation to the event as if it has nothing to do with him is the most glaring manifestation of his self-alienation and “forgetting of being” (Kundera, 17). K’s selfalienation also reveals itself when he listens and comments on the parable preached to him by the prison chaplain in the cathedral as if it is merely idle talk addressed to him, not realizing that “it is preached to him for a good reason: it is his story” (Thorlby,

68).

K’s detachment and self-estrangement are also brought about by his extreme involvement in the proceedings and the situation that allows him to forget himself.

K’s external gaze is one of his major flaws. The supervisor tries to draw his attention to this flaw when he tells him: “I can advise you to think less about us and about what may happen to you, and more about yourself” (Kafka, 9). Thus, he draws his attention to his over-absorption into trivial matters, such as who the people who come to

announce his arrest are and whether they are authorized to condemn him, but he does not think about himself or what he might have done wrong. His lack of introspection is what drives him away from some sense of self and makes him observe the whole event with the cold withdrawal of a stranger.

There is also an element of volition in K’s estrangement and withdrawal from self. For he claims that “if this was just a bit of make-believe, he would go along with it” (Kafka, 4). Thus, he intentionally chooses to lose and amputate his sense of self in this cycle of absurdity and, as a result, the self is annihilated. However, Kafka reveals in other cases that not only volition and free-will lead to self-alienation and annihilation of the self, but also, on the other extreme, tyranny and forceful domination bring about this state.

In The Trial , Kafka shows that the tyranny of the court and the advocates on whom the defendants depend leads to the total annihilation of the self. This is evident in Merchant Block’s case. For Block, a client of advocate Huld to whom K. resorts to help him with his case, almost permanently stays at Huld’s place, since his only concern is to ensure that Huld would effectively defend him. Block’s residence in a place other than his own is symbolic of man’s plight of non-belonging. Block emerges as a kind of homeless tramp, and the absence of a home is symbolic of the absence of a stable self.

Block’s tenacious clinging to Huld parallels K’s tenacious clinging to the court and its officials, since they both assume that salvation and the establishment of a self could be achieved only through proximity to them. Block’s whole life is wasted on this endless process of waiting, and no other option is open to him. He is also reduced to a mere puppet by the advocate. Hence, when the advocate orders Block to crawl on all fours, he immediately obeys and “acts out the animal-identity in himself”

(Goodman, 5).

The absence of a will or a sense of self-respect, revealed in the state of being reduced to bestial form, is a manifestation of man’s estrangement from the human condition, which is distinguished by having self, a will of one’s own, and an active mind. Block, however, does not have the ability to think for himself. He needs the advocate and even hires five more back-street advocates to think for him. Thus, he is merely a body with no self or mind. The advocate, who in turn represents the authority of the court, has the ability to eradicate and erase the self of the client and reduce him to a mere marionette. As a result, “the client forgot in the end about the

outside world and merely hoped to drag himself along this illusory path to the end of the case. The client was no longer a client, he was the advocate’s dog. If the advocate had ordered him to creep into his kennel under the bed and bark from there, he would have done it willingly” (Kafka, 151).

Advocate Huld and the court which Kafka use as a symbol of an oppressive society, therefore, serve to obliterate the self. The invasion of the self by an oppressive regime is symbolized by the warders’ invasion of K’s room and privacy.

The “violation of solitude” and “the rape of privacy” (Kundera, 111) are among

Kafka’s obsessions. They emerge as direct causes behind man’s estrangement and separation from self since they deprive him of contemplation and self-reflection. In addition, the fact that the warders take all K’s belongings including his clothes and underwear and deprive him of anything personal symbolizes the bombardment, dichotomization and extinction of the self.

As oppression emerges as an existential possibility, Kafka reveals that functionalism is another factor that severs and estranges man from self. The warders who come to arrest K. are the most obvious example of the alienating effect that functionalism exerts on man’s self. The warders, like K., are ignorant of the nature of his offense and are also ignorant of the identity of the man they come to arrest.

However, unlike K., they have absolute confidence and faith in the authorities they serve. They follow the orders without questioning them because they believe that

“there’s no room for mistake” (Kafka, 5). As a result, they become functionaries in the world rather than separate individuals. The two warders are, therefore, interchangeable and it becomes extremely hard to distinguish one from another. As a consequence, the self is totally annihilated and man becomes a total stranger to his inner being. The only knowledge or certainty he possesses is that he has a duty or a function to perform in life, but he is completely in the dark as to who or what he is.

Kafka also stresses his belief in the reduction of human beings and individuals to functionaries in the fact that he mentions Joseph K’s profession as a bank clerk and offers it as the only piece of information available. Through K., he reveals that this is the condition of man in an oppressive society and also prophesies the condition of man in the modern world. He also anticipates the living-dead existence of humanity and “the Waste Land as the landscape of modern man” (Politzer, 19).

“The Metamorphosis” is another of Kafka’s major works that reveals man’s self-alienation through functionalism. Gregor Samsa, the protagonist, is a traveling

salesman who wakes up one morning to find himself metamorphosed into a giant beetle. “The traveling salesman wakes up one morning and cannot recognize himself.

Seeing himself as a gigantic specimen of vermin, he finds himself in a fundamental sense estranged from himself. No manner more drastic could illustrate the alienation of a consciousness from its own being than Gregor Samsa’s startled and startling awakening” (Thiher, 148).

Furthermore, Samsa is only concerned with carrying out his job and catching the train to get to his office on time rather than contemplating his condition and the catastrophic transformation that has befallen him. “In his head he has nothing but the obedience and discipline to which his profession has accustomed him: he’s an employee, a functionary, as are all Kafka’s characters” (Kundera, 112). Samsa, like the warders in The Trial , is an example of a functionary who thinks only of his profession and function in society rather than the nature of his being and existence as a human. Like K. and the warders, he is an example of the “depersonalization of the individual” (Kundera, 107). Kafka, therefore, reveals the effects of being an inhabitant in a society that engulfs the self and reduces the importance of man only to his function and job in the world.

In addition, Samsa’s self-estrangement does not in fact start from the moment of his metamorphosis, but existed before his transformation as he was fully absorbed in his work with the sole concern of paying off his father’s debts. As a result, his family has been leading a parasitic existence by sucking his blood to the marrow in consuming the fruit of his labor. Thus, “not only is his labor alien to his true desires, but its sole purpose, its fruit – the salary or commission that it affords him – does not even belong to him. Gregor’s toil does not serve his own existence” (Thiher, 150).

“Through his sacrifice, Gregor had distorted his own self” (Corngold, 126).

His metamorphosis, therefore, “literally enacts the ‘loss of self.’ It makes drastically visible the self-estrangement that existed even before his metamorphosis” (Thiher,

150). As a result, Gregor’s “own inner being remains alien to him. It is for this reason that Kafka gave it a form that is quite alien to him, the form of a verminous creature that threatens his rational existence in an incomprehensible manner” (Corngold, 122).

“The horrible insect into which Samsa sees himself suddenly transformed, therefore, bursts in upon him just as the alien self, in the form of a monstrous gruesome court of justice bursts in upon Joseph K.” (Corngold, 123).

Furthermore, Gregor’s “profoundly alienated existence prior to his metamorphosis establishes the parallel to man’s fate after the expulsion from paradise” (Thiher, 152), which makes him doomed to a state of eternal loss and exile from his origin. He becomes an epitome of “the namelessness and facelessness of dehumanized humanity” (Politzer, 96). Samsa’s beetle-body also confirms the notion of the self as the inexplicable, since we come to see that “it is beyond our conception of the self” insofar as “the beetle embodies a world beyond our conscious as well as our unconscious imagination” (Corngold, 131).

Samsa’s plight is also the writer’s plight, who is drawn away and estranged from himself through absorption into literature. Literature serves as the song of the

Sirens that lures the writer away and fascinates him the way K. is fascinated and drawn into the world of the court with his whole being. In fact, Kafka spoke of the

“transformation of self into literature” (Kafka, x) which was his condition. Actually,

Kafka claimed that he was nothing but literature, and in a letter to Felice Bauer, he declared his inability to marry since “I am literature” (Heller, 2). This sense of “being an outsider, of having no existence except a literary one” (Heller, 2) reveals how “the creation harbors the creator and swallows him up to such an extent that he himself is denied any identification” (Politzer, 322).

The writer’s fascination with literature and his view of it as a god or a religion, as Kafka viewed it, therefore, serves to estrange him from the self and creates an isolated and alienated person. Kafka willingly chose to relinquish this self and lead the “selfless life of writing” (Heller, 24) by choosing to spend his entire life dancing the Maenadic dance held in honor of his god, Literature. Therefore, in

Kafka’s world, it becomes obvious that “man has now become a mere thing to the forces that bypass him, surpass him, possess him. To those forces, man’s concrete being, his world of life, has neither value nor interest: it is eclipsed, forgotten from the start” (Kundera, 4).

Gregor Samsa, in his beetle condition, also reveals another form of alienation, which is the existential state of alienation from the state of being human. For Samsa rejects and even feels disgusted by clean and fresh human nutrition. Instead, he develops a strong appetite for filthy and disgusting food given to animals and “from the dishes set down in front of him, he picks out for himself the ones that are spoiled, rotten and unfit for human consumption” (Corngold, 151).

His rejection of human food symbolizes his rejection of his humanity and the nausea it instills in him symbolizes his estrangement from his human self. He becomes a manifestation of “the individual’s estrangement from his humanity or

‘human species being,’ i.e., from the individual’s membership in the human species.

The individual is estranged from himself insofar as he is alienated from his essential nature as a human being” (Thiher, 148). As a result, he plunges into the unfamiliar, uncanny self of beetledom. In one of his letters to Felice Bauer, Kafka gave perfect expression to this state when he said: “life is merely terrible…and in my inmost self perhaps all the time – I doubt whether I am a human being” (Kafka, xii).

The feeling of alienation and estrangement which Kafka expresses in The

Trial is instilled through external forces that estrange man from the self. This is evident in the fact that K. is continually pursuing the court and the authorities to find out what his crime is, since he is ignorant of his offense. Thus, he has to depend on external forces (the world of the court) to arrive at a definition of his own self. Kafka, therefore, reveals how the establishment of identity can be dependent on external forces rather than on the individual’s perception of himself. It is also very ironic that

K. is chosen by the bank manager to guide the Italian businessman around the town.

For he can lead and guide people to different places but he himself needs to be guided by others into the labyrinth of the self. This confirms the fact that “one cannot know oneself in the same way that one knows things and people outside oneself” (Thorlby,

18).

J.M. Coetzee also poses the problem of man’s self-alienation in his novel Foe .

He presents the problem of the enigmatic quality of the self and the fact that it is a riddle in several ways. One of his means of expressing this problem is through Cruso, the man who inhabits an island with his manservant Friday. Susan Barton, the female narrator, who is cast out on Cruso’s island, tries to find out who Cruso is and how he was stranded on this island. When she asks Cruso these questions, he tells her a different story about himself everyday. This reveals his self-alienation, since he cannot give himself a definite identity or relate a single story about himself. The puzzled Susan, who cannot put her finger on who Cruso is, highlights the fact that the self is a puzzle and an enigma that no one can solve. It exists as an endless series of conjectures and deductions without any univocal definition.

Another means by which Coetzee portrays the self as a puzzle is through the picture he draws of Friday. In fact, Friday emerges as a symbol of the enigma of the self and its indeterminate identity. The endless questions Susan asks about Friday in her attempt to understand him are a further manifestation of the self as an enigma and an unsolvable puzzle. Furthermore, the fact that Friday’s tongue is cut out and that

“the only tongue that can tell Friday’s secret is the tongue he has lost” (Coetzee, 167) is another confirmation of the fact that the self is a riddle. It remains a question mark and a blank page just as Friday’s story remains the empty page in the novel. The fact that only Friday’s tongue can tell his story reveals that every human being is an enigma and a closed circle that no one can open and comprehend. Thus, no one can tell another person’s story, and, if he does, the story he produces is different from the original one. Therefore, story-telling, as Coetzee presents it, becomes a means of wiping out and distancing man from his true self, rather than preserving and materializing it. The story-teller is, therefore, like Foe to Susan Barton, an enemy to the self.

In her attempt to arrive at an understanding of the self, Susan resorts to the writer Daniel Foe and questions him as to whether she and other people are substantial beings or mere shadows. Foe answers her saying: “My sweet Susan, as to who among us is a ghost and who not I have nothing to say: it is a question we can only stare at in silence, like a bird before a snake, hoping it will not swallow us”

(Coetzee, 134). Foe’s words reveal that man is a mystery unto himself. Susan’s persistent query also highlights the fact that “the more powerful the lens of the microscope observing the self, the more the self and its uniqueness elude us”

(Kundera, 25). Thus, the more we contemplate it, the more “the weight of a self, of a self’s interior life becomes lighter and lighter” (Kundera, 27). Man’s self is, therefore, something he will forever remain ignorant of and the biggest question mark he cannot answer. It is a curiosity he stands before in amazement, just as he stands amazed before any uncanny phenomenon.

In addition to his depiction of the self as a riddle, Coetzee reveals through his three major characters, Susan, Cruso and Friday, the problem of identity. The problem of identity is the major problem Susan Barton struggles with in relation to herself and to Cruso and Friday. For Susan is a woman whose daughter was abducted and, as a result, she undertakes a journey in search of her lost daughter which results in her being stranded on Cruso’s island. The abduction of Susan’s daughter symbolizes the

abduction of the self, and her journey to search for and restore her daughter symbolizes her attempt at regaining and retrieving her identity. Thus, Susan’s abducted self, which her abducted daughter stands for, makes her live as a stranger and an alien unto herself. Therefore, she searches for it in an attempt at being reconciled with herself and perceiving her canny and familiar identity.

When Susan returns to England, a girl appears and claims that she is Susan’s lost daughter. Foe also tells her that this is her daughter. However, Susan insists that this girl is not her own daughter, and that “she stands for the daughter I lost in Bahia”

(Coetzee, 132). Thus, she is not her true lost self that has returned to her, but is merely a fake copy of it and a reminder and confirmation of the lost self that has not and will not return. Here Coetzee reveals in Susan’s inability to relate to the girl, as Kafka reveals Joseph K’s inability to identify his offense, that the lost self is irretrievable.

This is what makes man doomed to a perpetual existence of self-estrangement and alienation just as Adam feels ill-at-ease and incomplete without Eve.

Cruso, like Susan, embodies the loss of self and identity. When Susan asks him to tell her his story, she says: “But the stories he told me were so various, and so hard to reconcile one with another…So in the end I did not know what was truth, what was lies, and what was mere rambling” (Coetzee, 12). Thus, Cruso is a perfect example of a man who has no individuality or unique identity. He has lost his former self and lives an anonymous existence on his island. His inability to reconstruct a true story about himself, which marks his loss of identity and emphasizes “the uncertain nature of the self and its identity” (Kundera, 28), makes the island the most appropriate place for him to live in, since his solitary existence in it, save for the company of the mute Friday, makes it unnecessary for him to possess a recognizable self.

Through Cruso’s anonymous existence, Coetzee highlights the threat of self- annihilation that man faces. Like K., Cruso has no memory and is a tabula rasa character. He has no sense of time and keeps no records. Cruso’s refusal to keep a record of his story and life on the island marks his willful relinquishing of the self, which is probably the result of his long sojourn on the island which wipes out and engulfs his incentive to have a unique identity. His insistence on his isolation on the island, his enmity to his fellow humans (which is manifest in his hostile relationship with Susan) and refusal to have any contact with them are direct causes behind the annihilation of the self. Cruso’s loss of identity is related to his life as a recluse. Susan

advises and exhorts him to write his story by trying to convince him that his personal imprint is what would personalize him, since otherwise he would be merely a castaway with nothing special to distinguish him from others. He would be a mere nobody, but if he writes his story, he could escape from his anonymous existence and acquire a self. Susan here emerges as the Eros or life-giving force that fights against

Thanatos or death that threatens to eradicate one’s self and identity.

The threat of the annihilated self is also evident in Susan’s father’s name, which is originally Berton but “became corrupted in the mouths of strangers”

(Coetzee, 10), and hence became Barton. It reveals the threat of the annihilation of identity by outside forces, and explains why Susan is depicted as a person threatened with self-loss who is continually fighting for self-preservation.

The loss and annihilation of Susan’s self is further emphasized in the fact that when Susan returns to England, she lives in Foe’s house, since she has no home of her own. By lacking a home and a “room of her own” (Gallagher, 176), which was women’s plight as Virginia Woolf depicted it, Coetzee emphasizes Susan’s lack of identity. She also leads another person’s life, namely, Foe’s. Thus, she not only inhabits his home but also lives his life so that she relinquishes her own self and inhabits Foe’s self. She writes to Foe in one of the many letters she sends him: “I have your table to sit at, your window to gaze through. I write with your pen on your paper and when the sheets are completed they go into your chest. So your life continues to be lived, though you are gone” (Coetzee, 65). Thus, Foe is a parasite who feeds on

Susan’s self even when he is not present.

Foe’s existence as the host who feeds on his guest’s self is emphasized by

Susan when she blames him for forcing an unknown child into her life and making her claim that she is her lost daughter, when actually she bears no resemblance to the daughter she has lost. For Susan tells Foe: “She is not my daughter. Do you think women drop children and forget them as snakes lay eggs?…She is more your daughter than she ever was mine” (Coetzee, 75). Thus, Foe atomizes and bombards

Susan’s true self. He tries to stifle it by imposing a foreign self of his own invention on her. By attempting to silence and wipe out Susan’s part from the island story and imposing on her the alien girl story, Foe reveals the writer’s burden of falsehood, which brings about his self-estrangement, since it prevents him from self-expression and self-discovery. Coetzee also reveals through Foe’s domineering stance over Susan that “South Africans are subject to the Scylla and Charybdis of governmental control”

(Penner, 15), which, as a result, leads to their self-estrangement by having their voices silenced and their books censored. Foe also tries to brainwash Susan into believing that this is her true self, just as K. is brainwashed by the court into believing that he is guilty, and, as a result, always assumes the position of the culprit. Susan, however, unlike K., tries to resist the forces that plot against self and identity, and refuses to yield to them by being the creation they want. Thus, “she is well aware of the ways that people falsify stories” (Gallagher, 175). She resists and tries to combat oppression.

The fact that Foe, the fictional author, is a parasite feeding on his guest (the character) is also clearly dramatized when Susan sleeps with him. At this point, Susan relates: “Foe kissed me again, and in kissing gave such a sharp bite to my lip that I cried out and drew away. But he held me close and I felt him suck the wound. ‘This is my manner of preying on the living,’ he murmured” (Coetzee, 139). What further emphasizes the fact that Foe is an agent annihilating and engulfing the self is that when he has sexual intercourse with Susan, she says: “Then he was upon me, and I might have thought myself in Cruso’s arms again; for they were men of the same time of life, and heavy in the lower body, though neither was stout; and their way with a woman too was much the same. I closed my eyes trying to find my way back to the island, to the wind and waveroar; but no, the island was lost, cut off from me by a thousand leagues of watery waste” (Coetzee, 139). Thus, Foe brings about the total extinction of Susan’s self in this climactic moment. The irretrievable, vanishing island becomes the symbol of the loss of self and the place of belonging where it resides.

Friday, the tongueless man, is another example through which Coetzee embodies the threat of self-annihilation. Friday’s cut tongue symbolizes the eradication of self, since no identity could be established for someone whose tongueless existence prevents him from telling his story and individualizing himself.

He becomes a symbol of the anonymity and blankness of man. Man emerges as an incomplete being, which Friday’s cut tongue (the symbol of the absent and castrated self) represents, just as the initial K. (in Joseph K’s name) makes of him an incomplete person with no unique self, but rather a nobody, a mere manifestation of man’s nothingness and hollowness.

Furthermore, the fact that Friday dances in Foe’s robes and wears his wig marks the extinction of his unique self, since he places himself into somebody else’s clothes and belongings so that, like Susan, he lives Foe’s life. Friday’s integration

within Foe’s character again insinuates Foe’s existence as a parasite on Friday. Thus,

Foe is Friday’s and Susan’s foe, forever feeding on his characters. Friday’s whirling

Dionysian dance further expresses a loss of self, since it reveals his glaring unawareness of the “Cartesian split of self and other” (Gallagher, 179). For integration within a circle marks the loss of individuality. Here Coetzee expresses the belief that “the world is essentially made up of tribes” and that “the individual is nothing; the individual only realizes himself in the nation” (Penner, 9).

Through Friday, Coetzee also reveals that the absence of a self is directly related to a failure to command language, since “language is essential to preserve identity” (Gallagher, 38). One’s severed connection with language also makes of the individual a servile creation of others. The self he possesses becomes defined and established by external forces and his “existence is implicated by others” (Gallagher,

179). He therefore becomes the plaything of others, a piece of dough that people can shape as they like. Others shape different selves for him according to their whims and desires, and these selves are all alien to his true self. In addition, by creating alien selves for Friday, his true self is engulfed by these intruding foreign selves. Here

Coetzee points out the danger of “necklacing” (Gallagher, 37) or labeling, which is

Friday’s and the colonized’s plight, since the colonizer imposes a definition and a label that is foreign to the native’s life.

Susan sums up Friday’s problem of the lost self in an address to Foe: “Friday has no command of words and therefore no defense against being re-shaped day by day in conformity with the desires of others. I say he is a cannibal and he becomes a cannibal; I say he is a laundryman and he becomes a laundryman. What is the truth of

Friday?” (Coetzee, 122). Friday is like Proteus, the old man of the sea, an embodiment of different definitions and different selves, since Proteus takes different shapes, a lion, a bull, and so on, but his essence and original shape remain unknown.

This explains why Susan says that “Friday is Friday,” just as Proteus is Proteus. No definition of him could be verbalized or formulated. This is why he exists as a shadow and “his true reality lies elsewhere, in the inaccessible” (Kundera, 102).

In addition to the external factors that pose threats to the self, Coetzee reveals that man can be the agent of his own eradication. Man’s blindness is one of these factors which drive him away from recognizing himself and his identity. This is clear in Susan’s inability to recognize her daughter, who bears exactly the same name she does. Susan’s inability to recognize her daughter symbolizes a loss of self and the fact

that man often gazes on himself as something strange and alien. The fact that the daughter bears the same name as her mother makes her emerge as Susan’s double, the uncanny self that she fails to recognize.

Susan’s inability to see herself in the child makes her conclude that the child was sent by Foe. She dismisses the child as a nobody, and asks her to “go away and not to trouble me again” (Coetzee, 77). The fact that she sends her away reveals that external forces (like Foe) serve to destroy and bring about a total loss of identity. This makes Susan the parallel to Joseph K., who in his stubborn blindness and insistence on his innocence, fails to discover his offense, and to realize that the parable related to him in the cathedral is his story. The priest is, therefore, like the Sphinx in Oedipus

Rex , talking to K. about himself, whose blindness and narrow-mindedness distance him from the mirror that might allow him to see himself.

Like K., whose gaze is external and who is concerned with the world of the court, rather than introspection and self-discovery, Susan is driven away from selfreflection by being too concerned and absorbed by the people who might examine her life in the future. This is why she takes great pains and is so keen on searching for Foe to write her story. In fact, “the ruling passion in her life is to have her story told”

(Gallagher, 173). Her excessive concern with having her story presented in book form for public scrutiny is evident in her address to Friday: “Alas, we will never make our fortunes, Friday, by being merely what we are, or were. Think of the spectacle we offer: your master and you on the terraces, I on the cliffs watching for a sail. Who would wish to read that there were once two dull fellows on a rock in the sea who filled their time by digging up stones?” (Coetzee, 83). Thus, her extreme obsession with writing manifests a willful and foolish withdrawal from the self, which parallels that of Joseph K.

Susan’s self-detachment is also clear in her persistent attempts to teach Friday words, which make her focus her entire attention on him and, therefore, lose her grip on the person she might become. Friday is, therefore, a parasite that feeds on Susan.

She likens him to the old man of the river whose story she relates to Foe: “There was once a fellow who took pity on an old man waiting at the riverside, and offered to carry him across. Having borne him safely through the flood, he knelt to set him down on the other side. But the old man would not leave his shoulders: no, he tightened his knees about his deliverer’s neck and beat him on his flanks and, to be short, turned him into a beast of burden” (Coetzee, 148). There is an element of obligation in

Susan’s concern with Friday. She desires to help him but becomes trapped in his efforts to adapt. She is like the door-keeper in Kafka’s parable, ‘Before the Law,’ who wastes his entire life by keeping watch on the door and, as a result, is prevented from living his own life in a complete way.

As Foe exposes the factors that serve to bring about man’s self-annihilation and estrangement, it exposes on the other extreme the factors that could help him in creating a self. One of these factors is writing. For Susan believes that the writing of her story and its being put on paper will materialize her existence - and that of Friday.

(She does not know, of course, that for Friday writing means nothing and that his self only exists within the ocean, leaves and the twittering of birds on the island, and does not need to be expressed on paper). Thus, “until her story is written, Susan feels as though she lacks substance…She needs her story to be told in order to take shape as a human being” (Gallagher, 175).

Susan’s belief in the role of writing in creating and immortalizing the self explains her need to have Foe proceed with writing her story so that she can be freed and “liberated from this drab existence” (Coetzee, 63) in order to become an individual rather than a ghost and a shadow. She adds that “My life is drearily suspended till your writing is done” (Coetzee, 63). Thus, she needs Foe with his pen to give her substance and body, to breathe life into her lifeless, ghostly existence. She needs to become a real person so that the story of the island is not merely Cruso’s and

Friday’s but hers as well. Susan also looks forward to the wealth and material gain from which she will benefit if her story is written and published. “Figuratively, the wealth and freedom that she could achieve represent the ability to live a full, rich, independent and meaningful life, because she will have achieved an identity and a wholeness from the writing of her story” (Gallagher, 174).

Susan also expresses the belief that words are a means of confirming the presence of self and substantiality. She tells Foe that the words about her experience on the island and the words she wrote to him in letters are hers. She is the only person who wrote them, and this is what ensures her possession of a self. Thus, words are a means of possessing an identity, since words reflect a personal imprint and a unique self.

Another factor in preserving and creating a self is sleep. Foe explains to Susan the benefit of sleep. Through sleep, Foe says, we have the chance to “descend nightly into ourselves” and meet “our darker selves” (Coetzee, 138). Thus, it is a chance for

us to encounter our uncanny, hidden selves which are concealed by our waking life.

With this encounter we can have a firm grip on ourselves and get to know and encounter ourselves. Thus, sleep is a factor that enables us to maintain a self, whereas a continual waking life is a threat to its annihilation.

Coetzee also expresses man’s basic urge and need to create a self and affirm its reality. This urge is also Coetzee’s urge as a writer. For Coetzee’s devotion to

South Africa, his “bond with the South African landscape and his reluctance to become a ‘writer in exile’” (Penner, 4) is his means of self-preservation. For he says:

“I would probably feel a certain sense of artificial construction if I were to write fiction set in another environment” (Penner, 20). Susan expresses the urge to cling to a self in words written to Foe: “When I reflect on my story I seem to exist only as the one who came, the one who witnessed, the one who longed to be gone: a being without a substance, a ghost beside the true body of Cruso…Return to me the substance I have lost, Mr Foe: that is my entreaty” (Coetzee, 51). Thus, Susan wants

Foe to help her recapture and recreate her lost past, so that she can feel that she is somebody, not a mere shadow of Cruso’s story. Moreover, she wants to exist as a person, not merely as a story-teller, because she is an actual participant in Cruso’s and

Friday’s life on the island. Their story is, therefore, not theirs alone but hers, too.

Even though Susan resorts to Foe to help her establish a self, she refuses to be his slave until Foe writes her story. She insists on being the mistress of her own destiny and refuses to be Foe’s creation. This is clear when she tells Foe: “I am not, do you see, one of those thieves or highwaymen of yours who gabble a confession and are then whipped off to Tyburn and eternal silence, leaving you to make of their stories whatever you fancy” (Coetzee, 123).

In addition, when Foe tries to brainwash Susan into believing that the girl bearing her same name is her child, she tells him: “But how can we live if we do not believe we know who we are, and who we have been?” (Coetzee, 130). She insists that this girl is not her daughter and bears no resemblance to her, and she adds that if she were a gullible person who is “a mere receptacle ready to accommodate whatever story is stuffed in me, surely you would dismiss me, surely you would say to yourself,

‘This is no woman but a house of words, hollow without substance’” (Coetzee, 130).

Thus, she insists on clinging to her beliefs and her notion of herself.

Susan stands up to Foe when he threatens to destroy her identity. This is why she adds: “I am not a story, Mr Foe. I may impress you as a story because I began my

account of myself without preamble, slipping overboard into the water and striking out for the shore. But my life did not begin in the waves” (Coetzee, 131). She insists on her substantiality, and tells Foe: “I am a free woman who asserts her freedom by telling her story according to her own desire” (Coetzee, 131). Thus, she refuses to be

Foe’s plaything and slave. Susan, therefore, in her insistence on being free and the mistress of her own destiny, emerges as Joseph K’s foil, since K. refuses to bear any responsibility for himself but leaves his life in the hands of the court and the people around him.

However, Susan tells Foe: “The story I desire to be known by is the story of the island” (Coetzee, 121). Her indifference to the story of Bahia and the loss of her daughter reveals two things. First, her desire to relinquish the Bahia story symbolizes a relinquishing of the self (since the Bahia story is part of her). The lure and temptation of being part of the island story leads to a partial loss of self, due to her desire to be a character in a story. The story-teller (Foe) is therefore the agent and the catalyst that brings about a loss and estrangement of self. At the same time, Susan’s insistence on being known through the story of the island could have a positive aspect to it. The story of the island could be the place where her true self resides, whereas the

Bahia story could be the locale of a false self. Thus, Susan’s insistence on immortalizing and breathing life into the island story could be her means of preserving her true self.

Even though Susan insists on having a self, we see her wavering between the certainty and doubt of possessing one. She embodies man’s plight of being lost in the world, searching for an identity that keeps appearing and disappearing. For Susan tells

Foe: “I thought I was myself and this girl or creature from another order speaking words you made up for her. But now I am full of doubt. Nothing is left to me but doubt. I am doubt itself. Who is speaking me? Am I a phantom too? To what order do

I belong? And you: who are you?” (Coetzee, 133). Thus, Susan fluctuates between certainty of being and doubt of being, which leads to her search for identity. Susan’s words, apart from highlighting her fluctuation between certainty and doubt, reveal that “the quest for the self always ends in a paradoxical dissatisfaction” (Kundera,

25). For the fundamental underlying question behind Susan’s conversation with Foe is: “If stories give us our identities and if we are written by others, do we exist for ourselves?” (Gallagher, 179).

Man’s urge to create a self is also portrayed by Coetzee through Friday. The fact that Friday consistently plays a single, persistent tune on his flute seems to be his only means of establishing an identity. His singular unique tune is his means of asserting that he has a unique self. Susan also infers that Friday’s immersion in a circular dance is his means of transporting himself from his life in England to return to his former life in Africa or to Cruso’s island where he belongs. For the dance puts him in a kind of trance through which he can escape from his unfamiliar surroundings and return to his familiar milieu where his true self resides. Thus, the dance is the means by which the self could be restored. The dance, one realizes, is a double-edged weapon since it serves both to restore and annihilate the self.

The doubtful girl who is supposed to be Susan’s daughter is another example of man’s overpowering urge to cling to a self and a substantial existence. The girl insists that Susan is her mother and tells her: “You are my mother, I have found you, and now I will not leave you” (Coetzee, 78). This attitude symbolizes man’s urgent desire to hold on to a self and an origin so as to escape the fate of having a selfless and anonymous existence. Thus, Coetzee in this way reveals and emphasizes man’s condition of self-alienation, since he continually embarks on a journey and carries out an investigation, like Joseph K., to search for an unknown identity.

Like Kafka, Coetzee also highlights the problem of the questionable and doubtful existence of the self. The different stories that Cruso relates about himself and the impossibility of clinging to an original story and identity represent not only man’s self-estrangement, but also the vanishing self which is lost like the ship that brought Cruso to the island. Just as it is impossible for Susan to dive and retrieve tools from the wreck, it is impossible to retrieve Cruso’s lost self. The various stories that he tells about himself express Coetzee’s view of the questionable and doubtful existence of a self. They also express and emphasize that each man has plural selves and characters in one person. Hermann Broch claims that “it takes several lives to make one person” (Kundera, 56). Thus, defining a singular self is an impossibility. In fact, Coetzee himself embodies several lives as “J.M. Coetzee the teller of tales, the illusionist, the fabulist and wordsmith” (Penner, 21). The fact that Cruso does not keep a journal also suggests that the self cannot be preserved or maintained. For there is no record to give a hint to future castaways about Cruso’s identity. He lives as an enigma and he dies as a riddle that no one can solve. The absence of a hint or clue that

would reveal Cruso’s identity is Coetzee’s means of voicing the highly doubtful existence of a self in the first place.

This problem is also apparent through the character of Susan, who has the ability to adapt to any place. Once she leaves Cruso’s island, which was at first a strange, uninhabitable place for her, she longs to go back to it and feels that it is her home, thus emphasizing Cruso’s belief that not every castaway is lost, since the place on which he is stranded could be the place where he feels at home. Then when she goes back to England and lives in Foe’s home, she at first feels uncomfortable in it.

She then writes to Foe, in reference to his home: “I feel as we feel toward the home we were born in. All the nooks and crannies, all the odd hidden corners of the garden, have an air of familiarity, as if in a forgotten childhood I here played games of hide and seek” (Coetzee, 66). The fact that Susan adapts so quickly suggests that her possession of a unique self, which manifests itself in having a settled home, is totally absent and perhaps questionable.

When Susan’s supposed girl sobs and tells Susan that she has forgotten her,

Susan exclaims, “I have not forgotten you, for I never knew you” (Coetzee, 174). This reveals that she does not know herself, since she fails to recognize her daughter.

When the girl claims that Susan is her mother, she is told by her: “You are fatherborn. You have no mother. The pain you feel is the pain of lack, not the pain of loss.

What you hope to regain in my person you have in truth never had” (Coetzee, 91).

Here Coetzee suggests through the motherless child that the existence of a self may be myth, since the existence of the motherless child suggests that man lacks an origin.

Later, Foe asks Susan about the daughter she lost in Bahia and attempted to find: “Is she substantial or is she a story too?” (Coetzee, 152). He thus implies that Susan herself is a story, and casts doubt on her genuine reality.

Coetzee also poses the problem of the self through Friday. For the absence of a definite definition of Friday, whose speechlessness makes him the object of conjecture, turns him into a symbol of man’s hollowness and lack of self. Susan says of Friday: “He is the child of his silence, a child unborn, a child waiting to be born that cannot be born” (Coetzee, 122). He is “unborn” because he has no self to breathe life into his body, and he “cannot be born” because his silence makes it impossible for anyone to materialize and individualize him. He therefore remains unborn and anonymous to the world. Friday’s silence and speechlessness, which prevent Susan from identifying him and eternalizes his existence as an “unborn” child, is Coetzee’s

way of saying that the existence of the self may be an illusion. Friday’s inability to present a self seems to be the only message that his silence conveys.

It is worth mentioning that Friday’s silence also could be his means of protecting and sheltering the self inside him, since by verbalizing it, the self is threatened with annihilation and distortion. Thus, as Kafka is a door-keeper to his works, Friday is a door-keeper to the self he possesses, keeping it safe and secure within himself and never allowing it to enter the world and face life’s dangers. It remains “unborn” and embedded within him as he is “unborn” to the world and remains sheltered in his mother’s womb. His attitude could parallel Kafka’s unfulfilled will of having his books destroyed, rather than published. For as Kafka may have wanted to withhold his books to spare them from false criticism, Friday actualizes the salvation of his story by engulfing and embedding it within him.

The problem of the absence of a unique self is also presented by Coetzee through the figure of Foe. Foe plays the double role of writer-reader. He, like Proteus, takes different shapes so that identifying his essential nature becomes an impossible task. Thus, the self is unreachable and intangible, like Joseph K’s concealed and invisible judge, who in his unapproachability, stands as an eternal threat and confirmation of the impossibility of K’s arrival at self-discovery.

Coetzee, like Kafka, delineates the role of external forces in instilling man’s self-alienation through his dependence on these forces to establish his identity. Susan is dependent on the writer Daniel Foe to write her story and establish an identity for herself and Friday, since she begins to “doubt the substantiality of her experiences, her story, and herself” (Penner, 118). Thus, when she searches for Foe, she is not only in search of an author, but “of her own ontology” (Penner, 121). However, creation of an identity is not established from within but is external. Just as Joseph K. pursues the court and its officials to determine the nature of his offense, Susan perpetually pursues

Foe and clings to him to create a self for her and Friday.

However, Foe, as his name indicates, turns out to be an enemy. Instead of creating a self for her, he serves to annihilate and bring about its total destruction, since he attempts to write a false story about her to please the readers. (Foe is here the parallel to Coetzee, who alters and deforms Robinson Crusoe by imposing the story of

Foe on it. Therefore, the writer is a destroyer and an enemy to the survival of the self.)

Just as the picture of the magistrate that K. sees makes of him a God-like figure,

Susan perceives Foe to be a God-like figure. She thinks of him as “a steersman

steering the great hulk of the house through the nights and days, peering ahead for signs of storms” (Coetzee, 50). She sees him as the prescriber of her destiny and her words comment on “his God-like control” (Penner, 178). But unlike K., who is forever servile to the court and its officials, Susan is always wavering between servility to Foe and rebellion against him.

Susan at one point writes to Foe: “Days pass. Nothing changes. We hear no word from you, and the townsfolk pay us no more heed than if we were ghosts”

(Coetzee, 87). She again emphasizes the fact that she and Friday have no substantiality, and this is why they are treated by everybody as if they were nonexistent. Thus, Foe is the savior on whom they depend, since he is the one who is expected to bring them back to life, to bring about their departure from Hades and their entrance into the world of the living.

Finally, in addition to exposing man’s dire self-alienation through his inability to form an internal and individual self-perception, Coetzee, like Kafka, presents the painful problem of man’s alienation from his human self. This is apparent through the character of Cruso. Coetzee reveals that Cruso is not only alienated from the self but also from his human self and his humanity. When Susan relates her tale of woe and the misfortune that brought about her desertion on his island, Cruso “gazed at me more as if I were a fish cast up by the waves than an unfortunate fellow-creature”

(Coetzee, 9). Through his coldness, indifference and clotted emotions, he epitomizes the detachment of man from his fellow man and his estrangement from all human feelings such as sympathy and compassion. Cruso’s alienation from his human self is finally manifest in the fact that he has no desire for Susan as a woman. He seems to have lost all contact with human sensations and with manly feelings and is reduced to an imitation of a human being.

Chapter Two

The World as a Strange Place

I am standing on the platform of the tram, utterly unsure of my place in this world, in this city, in my family.

Franz Kafka, “The Passenger”

It is a twilight world, a dark world, a world in which one goes out into the labyrinthine town without having anything to do there, a world in which one is alone, knowing neither who he is nor whose son or father or lover he is, nor perhaps whether he is a man.

Franz Kafka, “Preparations for a

Wedding in the Country”

As the self emerges as a stranger and an alien, the world also emerges as a strange, unfamiliar place in which man cannot find his bearings and is continually lost and unable to find a place of belonging in it. The world’s assumption of an

‘unheimlich’ face which man cannot comprehend instills in him a sense of homelessness and desolation, and also the longing for a once-familiar world. This world would offer him the opportunity to overcome his predicament of being a stranger and an outsider who cannot be incorporated into the universe.

In The Trial

, Kafka depicts man’s estrangement from the world and explores the different causes behind his alienation from the world and his isolation from the human species. Through Joseph K’s ordeal, Kafka reveals that man’s alienation from the world stems from its becoming an alien place with many perplexities and complications. For like most Kafkan heroes, Joseph K. wakes up into a nightmare to find himself “exposed to an incomprehensible fate, as to a sharp, cold wind” (Politzer,

346). He wakes up to find himself in an absurd and inexplicable situation of groundless condemnation and accusation. The strange court of law before which he is

tried and the soulless, ignorant and insipid warders who come to arrest him without offering an explanation parallel the absurdity and incomprehensibility of the world. It is a “world of uncertainty and insecurity, of fear and trembling” (Warren, 106).

“You ask for sense and you are putting on the most senseless exhibition yourself” (Kafka, 10). This is what K. tells the supervisor when he tells him that there is no sense in telephoning a lawyer to defend him. K., therefore, realizes that this is a senseless world that has a logic of its own. It is a world he cannot decipher or fit into.

“It is a world seen slightly askew” (Warren, 112). K. seems to be lost in a world which resembles that of “Plato’s cave which a malicious God has paneled with mirrors. The prisoner thirsting for true knowledge now perceives actual shapes, not shades, yet the concave walls of the cave reflect these forms in grotesque distortions”

(Draper, 1948).

The fact that K. finds himself thrown into an uncanny and absurd situation parallels, or rather dramatizes, Kierkegaard’s description of the plight of modern man who is thrown into the universe and struggles to deal with it through this plight which is not of his choosing. Like Joseph K., who is summoned for an unknown and invisible reason, “man is called into this world, he is appointed in it, but wherever he turns to fulfill his calling he comes up against the thick vapors of a mist of absurdity”

(Politzer, 179).

Joseph K’s plunge into an absurd and ambiguous situation and Frau Grubach’s comment: “What things happen in this world!” (Kafka, 15) reveal Kafka’s view of the world as a storehouse of strange occurrences in which man becomes an Alice in

Wonderland. He reflects “a universal discord, a break between man and his world”

(Politzer, 334). Furthermore, Kafka not only depicts an incomprehensible world, but he also draws attention to the idea that all attempts at understanding it are useless and unnecessary. He shows that one should just accept the world with all its strangeness and inscrutability since all attempts at deciphering its mysteries are futile. In fact,

Frau Grubach tells K. that his arrest “seems to me like something scholarly which I don’t understand, but which one doesn’t have to understand either” (Kafka, 15). Frau

Grubach’s words evoke the “sense of life as not being inherently meaningful”

(Josipovici, 15), which runs throughout almost all of Kafka’s works.

In addition to the problem of the world’s incomprehensibility, Kafka’s

The

Trial explores other causes behind man’s estrangement from the world. The curse of exclusion is another direct cause of man’s alienation from the world.

The Trial is “a

story about a man always awaiting judgment” (

The Trial , ix). The fact that Joseph K. is always awaiting judgment and the pronouncement of his offense highlights his position as an excluded, rejected stranger from the world. Joseph K. is never seen as being part of or assimilated into the world, but rather, as marginalized and completely

“disconnected from the rest of the world” (Szanto, 20).

K. always assumes the position of the accused, condemned culprit. He is doomed to live the life of the exile and the frowned upon individual. Joseph K’s doom is the doom of “man alone, man hunted and haunted, man confronted with powers which elude him, man prosecuted and persecuted. He is the man eager to do right but perpetually baffled and thwarted and confused as to what it is to do right…the man in search of salvation” (Warren, 116) and eager for inclusion and acceptance.

K. always feels rejected by the world. When the bank manager sends him on a business assignment outside the office, he does not feel valued due to his distinction and ability, but senses suspicion against him. He believes that others are taking every opportunity to get him out of the office so that they can check on his work, or even try to cause trouble by plotting against him or turning his clients against him. He always feels that he is being watched and under the surveillance of the deputy manager. Thus,

K. emerges as a man against the universe. He always feels that the whole world is plotting against him. His suspicion of everyone, which heightens his sense of nonbelonging and exile symbolizes “man’s forlornness in a wintry world” (Politzer, 88).

The world’s hostility, which dooms man to endlessly grope its corners in utter loss and helplessness, is further emphasized by Kafka through the atmosphere of darkness that prevails everywhere in The Trial . K. is always lost in an endless cycle of darkness and opacity, striving to find the light that would guide him out of his bat-like existence. He is always alone and wandering in isolation. He has no companion or friend to trust. Instead, he always lives in doubt and is suspicious of everyone.

Wherever he goes, he feels that someone is watching him and planning to trick and harm him.

Thus, the world emerges as a place in which man has to watch out and be heedful of the conspiracies and ambushes laid for him. It is not a place where he could live in peace and ease and feel at home. It emerges as a place of punishment and expulsion. It becomes “the place where we went astray, it is the fact of our being astray” (Altmann, 51) and the place in which man keeps waiting and yearning for his lost paradise of belonging. Man’s life and struggle on earth is, therefore, a

confirmation of the fact that “mankind has lost its home” (Altmann, 53) and that man is “the exile from Paradise, who tries to gain Life but who is not able to take the road to Sinai” (Altmann, 53).

K’s endless loss in darkness, and the fact that we find him always “trying to get his bearings in the darkness” (Kafka, 84), symbolize Kafka’s view of the world as a trap or a labyrinth. This is evident in the endless corridors and passageways leading to the court offices which Joseph K. strives to enter and which reveal Kafka’s portrayal of the world as a maze. The world is a place of unfamiliarity in which he gets lost and bewildered. This absence of the feeling of belonging and familiarity is what intensifies man’s sense of alienation. Kafka’s depiction of the world as a labyrinth and his exploration of K’s possibilities of existence and attempts to escape this maze, therefore, reveal that his novel is “an investigation of human life in the trap the world has become” (Kundera, 26).

In addition, the fact that the court usher tells K. “there’s only one way”

(Kafka, 52), when K. asks him to guide him through the court rooms and show him the way, reveals that K. is the only person who cannot see or know the way when it has become obvious. K’s problem or flaw seems to be a problem of blindness and insight. He fails to see and perceive things clearly and this is why he needs someone to guide him. His Oedipus-like blindness is what estranges and isolates him and makes him feel out of place in the world. Furthermore, his blindness is something of his own choosing. For when the usher tells him: “you haven’t seen everything yet”

(Kafka, 52) on their way to the court offices, K. says: “ I don’t want to see everything” (Kafka, 52). Thus, he refuses to open his eyes to everything around him, and this is what leads to his exile from the world. His withdrawal and desolation in the world is, therefore, his own doing.

K’s estrangement from the world is also evident in the fact that he fails to see that the three men, Rabensteiner, Kullych, and Kaminer, whom the court ask to accompany K. to the bank, are actually officials from the bank he works in and are not total strangers and people he is seeing for the first time as he assumes. Thus, K. is a man who is isolated and cloistered. He is blind to the obvious things in his life and he fails to recognize what he sees everyday. Joseph K’s blindness, therefore, symbolizes “man’s unfamiliarity with his familiar surroundings and his alienation on earth” (Politzer, 12).

Through K’s unseeing and unperceptive eyes, Kafka not only reveals the individual’s hamartia of blindness as a cause of alienation, but he also reveals the inability to recognize what is supposed to be familiar. He dismisses the familiar as totally unfamiliar, as the effect of external forces and a direct result of living in an oppressive situation. Kafka makes clear through Joseph K’s blank memory and blind eyes that oppression can serve to obliterate a person’s memory about his world and surroundings, since it absorbs him in alien demands and causes him to forget his true possibilities.

Thus, K. becomes absorbed in the warders, supervisor and the entire world of the court and loses his grasp of his world. This shows the effect of oppression in annihilating and eradicating one’s sense of awareness and familiarity with the world.

It has the effect of creating an individual who lives as if he is living his life for the first time, or whose life resembles a dream. We see in Joseph K’s situation the recurrent Kafkan situation of “the protagonist who knows only that the change that has taken place has separated him from the life he had been leading” and is now, as a result of this change, thrown into “the new world” (Szanto, 24).

Through Joseph K’s predicament, Kafka brings in another factor behind man’s alienation from the world, namely, difference and otherness. K’s problem of nonbelonging and estrangement is evident in the fact that he feels like a fish out of water in the court rooms. He finds it difficult to breathe in such an atmosphere. K’s situation is symbolic of man’s situation in the world. He feels out of place and alienated not only because he cannot comprehend the world but also because it is different from what he knows. He cannot be assimilated to it. Joseph K. “who still believes himself to be acting within the context of his old world at last feels the absence of context in a world void of related objects and beings” (Szanto, 31).