Reader

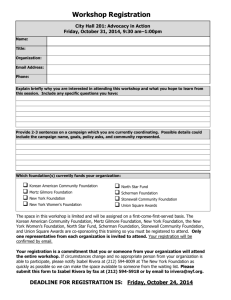

advertisement