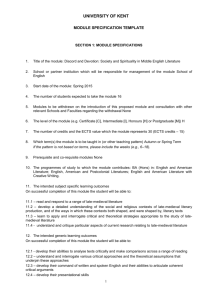

religi~1.doc

advertisement

Religious Women Since biblical times, stories have dealt with women and their concerns with sex, men, children, virginity, and religion. A close look at medieval works like the Canterbury Tales, Piers Plowman, and The Book of Margery Kempe reveals a common theme of pilgrimages, in which religious women play a key role in each of the story plots. Medieval pilgrimage literature as a genre necessarily limits its scope to people who would make a pilgrimage, and therefore the genre of these books effects the role and varying degree of religious life given to the different women characters. We shall now take a closer look at the characters of Holy Church in Piers Plowman, Margery Kempe in The Book of Margery Kempe, and The Wife of Bath, Prioress, and The Second Nun from the Canterbury Tales. The genre requirements of Piers Plowman have a direct effect on the degree of religiousness of Holy Church. Piers Plowman is an allegory, the main objective of which is teaching. Will, the main character, is struggling with the problem of searching for how he can save his soul. It is only fitting that the female character who is in charge of helping him find salvation seems to play the role of a “true” religious character. Holy Church begins to comfort Will by stating “Moderation is Medicine no matter how you yearn” 1 (Passus I, 35). She explains to Will that we have been given food, clothing, and shelter which “is the first prerequisite for Christian perfection” (Bloomfield 152). He then questions how these goods can be divided among the world and Holy Church replies it can be “found in the Bible in Jesus’ command to render unto Ceaser that which is Ceaser’s and to God that which is God’s” (Bloomfield 152). To help Will learn how to save his soul she explains the difference between the “Castle of Care” and “the tower on the hill-top”, one being heaven and the other hell. Even with all this explaining Will still questions further “Yet I’ve no natural knowledge, you must teach/ me more clearly” (Passus I, 137). To this “he is told he has a natural knowledge of what to do and how to love if he would but perceive it. He is told to teach others the truth and to look to Jesus, who provides an example for us all. Share your wealth with others, Lady Holy Church continues, Chastity without charity is worthless, and the greatest sinners are the clergy. Faith without works is dead, and ‘give and it shall be given unto you’” (Bloomfield 153). In other words “Holy Church is saying that love arises out of a spiritual capacity which is itself generated by a Kynde Knowledge in the heart” (White 53). 2 After hearing, such an eloquent explanation to Will’s questions there should be no doubt that Holy Church is anything but a perfect Christian. It seems only obvious that Langland would have Holy Church be perfect since she is a fictitious character as opposed to Margery Kempe, and has the sole and brief purpose of helping Will better understand how to reach salvation. Knowing this, it is ironic that in the beginning of Passus II with the introduction of Meed, Holy Church lets unchristian sides pass through. When Will questions whom Meed is Holy Church replies “That is Meed the maid who has harmed me very often/ and maligned my lover-Lewte…/ In the Pope’s palace she is as privileged as I am,/ But Soothness would not have it so, for she is a bastard,/ And her father was false-he has a fickle tongue…/ Like Father Like Son…/ I ought to be higher than she: I came of better parentage./ My father is the great God, the giver of all graces,/ one God without beginning, and I’m his good daughter…/And the man who takes Meed-I’ll bet my head on it-/ Shall lose for her love a lump of caritatis” (Passus II, 20-35). Holy Church shows a bit of hatred and jealousy towards Meed, which are listed as two sins in the bible. Her character turns out to be not as perfect in the religious realm as was first portrayed. 3 The Book of Margery Kempe is an autobiography in which Kempe relays her experiences to a priest to have them written down for others to read. Since this selection is the only one of the three based on a real person one might expect to find a rather flawed human being. This however does not seem to be the case. “The Book insists, through the declarations of Christ in Margery’s visions, that as a contemplative she is martyr to and elevated above the mainstream. At one point Christ proclaims Margery equivalent to four of the greatest martyrs (51); at another he assures Margery that he has ordained her to be a “mirror” for spiritual attainment among her contemporaries (186)” (Fredell 137). Margery’s true testaments of faith are her holy visions that often entail much sobbing and crying. “She had so much feeling for the manhood of Christ, that when she saw women in Rome carrying children in their arms, if she could discover that any were boys, she would cry, roar, and weep as if she had seen Christ in his childhood” (MK, 123). The book also claims that “sometimes she heard with her bodily ears such sounds and melodies that she could not hear what anyone said to her at that time unless he spoke louder” (MK, 124). “And this creature wept and sobbed as plenteously as though she had seen our Lord with her bodily eyes suffering his Passion at that time” (MK, 104). Margery’s tears are not her 4 own doing though for she has received “the gift of holy tears as a mark of special grace and Margery’s membership in the Holy Family” (Fredell 155). Most of “Margery’s visions focus on the royal family of God as if she were a lady of the bedchamber” (Fredell 139). Margery marries Christ as he says “I take you Margery, for my wedded wife” (MK, 123) and then goes to bed with him for the first time. “Therefore I must be intimate with you,…Daughter, you greatly desire to see me, and you may boldly, when you are in bed, take me as your wedded husband, as your dear darling, and as your sweet son, for I want to be loved as a son should be loved by his mother, and I want you to love me daughter, as a good wife ought to love her husband” (MK, 126-7). By this Margery has become a true mother to Jesus Christ and to the whole world (MK, 127) as well as Christ’s daughter and wife. Margery’s love for Christ went a lot farther than visions however as “she wore a hair-shirt, and did great bodily penance and wept many a bitter tear, and often prayed to our Lord that he should preserve her and keep her so that she should not fall into temptation, for she thought she would rather have been dead than consent to that” (MK, 49). Margery’s religious greatness is better shown to the reader with her “associations with St. Bridget and Julian of Norwhich, whose 5 visionary texts Margery and her spiritual advisors clearly knew” (Fredell 140). “Bridget’s book (Liber Celestis) is wholly taken up with visions, not with any conscious narrative of her life. In the Revelations of Julian of Norwich… we are given a brief glimpse of Julian’s Illness,…but it is brief and quickly subordinated to ‘showings’ of such theological depth that we cannot ignore Margery’s distance from Julian’s status and training as a num. Overall, Margery’s Book differs from these two predecessors in it’s translation of mystic status to body politic, where Kempe was neither an avowed anchorite virgin nor an established visionary in residence, but a lay wife and mother struggling all her life for redefinition” (Fredell 140). “Christina Mirabilis, Mary of Oignes, and Katherine Seneis may have served as models for Margery’s own martyrdom,” (Fredell 141) and she is a “visionary like St. Bridget and a contemplative martyr like Mary of Oignies” (Fredell 142). The genre of The Book of Margery Kempe allows for a rather onesided view of her spiritual life. We see her less spiritual side when we hear how she wished to sleep with a man, but he refused. One can only speculate 6 of other sinful acts that were not included by her since it is her autobiography and she included what she wished. The majority of the book however, is of godly actions in accordance to God’s wishes. However, why would the book not be of a purely religious nature for “this creature was inspired with the Holy Ghost, and bade her that she should have a book written of her feelings and her revelations” (MK, 35). The genre of the Canterbury Tales is far different from that of the other two books, for it has a humorous story telling style, and it is this genre that allows for the variety of characters by Chaucer. Like the other two books in which the religious women were involved in a pilgrimage so too are the women in Chaucer’s book. The Wife of Bath is possibly the most known female character in the Canterbury Tales. “It is easily apparent that the wife must have been a valuable member of the Canterbury company because of her wide experience with Pilgrimages- three times in Jerusalem, to Rome, to Boulogne, to St. James’s in Galicia, and to Cologne” (Lumiansky 120). Rather than hearing about her experiences on these pilgrimages Chaucer focuses her character’s Prologue on her experiences with her five husbands, which “qualifies her as an expert, but though she flaunts the authorities, she exhibits an uneasiness about the number of her marriages” 7 (Huppe111). “She maintains that God, rather than forbidding more than one marriage, instructed us to multiply” (Lumiansky 122). Therefore, while having multiple marriages is not sinful within itself it is her reasoning behind these marriages. “The issue of procreation and marital sex is another area where the presence of rebellion and conformism is striking. The wife’s text includes some memorable celebrations of her wish for sexual fulfillment and happiness, something always condemned by authoritative Christian tradition, as the Wife knows very well” (Aers 148). The reasoning for the wife’s lengthy account of her five husbands “has served to illustrate her principal theme- that if a husband does not grant his wife sovereignty, he will suffer great woe” (Lumiansky 125). The Wife of Bath’s Tale follows along this theme of sovereignty in which a Knight receives true happiness once he has granted his wife sovereignty. Marriage for The Wife is not for sexual pleasure but “it provides her with a vast sense of power in the exercise of her sovereignty; it makes her feel the godlike powers which the serpent promised Eve would follow eating the apple” (Huppe 117). Her attitude toward men is entirely different from Margery’s who feels “it is the wife’s part to be with her husband and to have no true joy until she has his company” (MK, 67). 8 So why then is The Wife on the Pilgrimage if the life she leads is not that religious? According to Huppe, she is on the pilgrimage in search of a sixth husband, or to possibly fill an empty space (109). The type of woman the wife is “her voice and learning and bodily experience is irrevocably linked to a male author” (Fredell 143). The genre allowed Chaucer to choose the Wife to be less Godly than the others who accompanied her on the pilgrimage. The prioress is another comical Christian character that Chaucer puts on the Pilgrimage. The prioress is not an ideal nun. “Her table manners are above reproach, for her interest in etiquette is great. In this matter, as in the mention of her way of speaking French, her fine clothes, her ornaments, and her pets, Chaucer is laughing at this nun who interests herself in the behavior of fashionable people” (Lumiansky 79). The average reader in the Twentieth century might find her grandeur attitude as an unreligious attribute, but “In Chaucer’s day the majority of nuns adopted their way of life for economic rather than for purely religious reasons, and they were most frequently from the upper classes” (Lumiansky 79). The prioress shows an exaggerated amount of sensitivity in which she weeps at “ a dead or bleeding mouse caught in a trap, and especially if one of her “smale houndes” 9 dies or is beaten” (Lumiansky 80). Even with exaggeration in dress and attitude Chaucer did not leave her without a religious side. After all she is a nun. “The Prioress’ Prologue and Tale show clearly, by means of their atmosphere of sincere religious devotion, that the bantering tone which Chaucer used in describing Madame Eglentyne in the General Prologue was not intended to indicate that she is open to adverse criticism on matter of fundamental faith” (Lumiansky 81). While the Prioress is probably not as holy as one might have thought a nun would be Chaucer seems to have at least made her more holy than The Wife of Bath. Lastly we can take a look at the character of The Second Nun. Chaucer mentions very little of her in the General Prologue except ”Another Noone with hire hadde she,/ That was hir chapeleyne, and preestes thre” (I, 163-64). “The absence of a portrait drawn by the pilgrim narrator signals the author’s self-effacement within the Canterbury Tales with respect to the presentation of the Nun, and we are given the voice of the Nun in her performance” (Arthur 218). “Chaucer fittingly assigned to the Second Nun not just any saints life but the life of a female saint” (Lumiansky 225). We are meant to take the tale as a description of the life led by the Second Nun. “The insertion of “us” and “me” permits us to hear the voice of the Nun 10 as inspired by the early Christian martyr Cecelia, while Cecelia achieves renewed influence through the Nun’s telling” (Arthur 219). The Second Nun comes across as the only pure religious woman in the Canterbury Tales. Although not much is mentioned about her, can we assume that Chaucer intended for her to appear as a holy woman who might partake in a pilgrimage during this time? Although the Canterbury Tales, The Book of Margery Kempe, and Piers Plowman are all books based on pilgrimages, the genre of the books has directly effected the degree of holiness of its female characters. From women searching for future husbands, to nuns caught up in glamour the Canterbury Tales allows for a comical view of religious life. Langland in Piers Plowman creates an allegorical setting to allow for his creation of Holy Church. While her character has her flaws she also appears to come close to leading a true holy life. The Book of Margery Kempe, being the only true story of the three, would seem to come with the most flaws of its characters. Since this is not so, one can only speculate if the fact that Kempe was in charge of what was included had anything to do with her flawlessness. So as seen in Piers Plowman, The Book of Margery Kempe, and 11 the Canterbury Tales the genre is directly related to the varying degree of holiness of its characters. 12 13